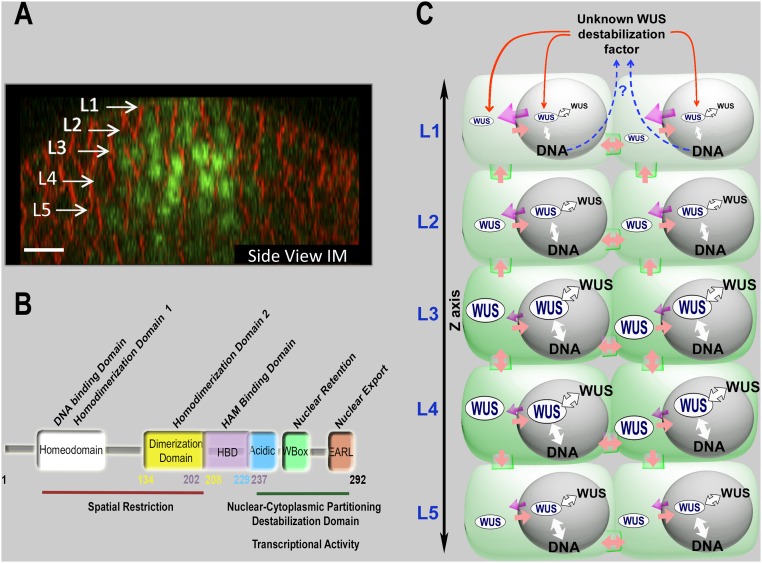

Fig. 5.

A sketch illustrating the control of WUSCHEL levels and spatial patterning in IMs. (A) A side view of the IM showing the spatial pattern of eGFP-WUS expressed from the WUS promoter. White arrows show different cell layers. eGFP (green) and FM4-64 (red). (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (B) The function of individual domains of WUS protein as inferred from the structure-function analysis and the ectopic overexpression of WUS. The functions of individual domains are depicted on WUS protein. The numbers indicate position of amino acids, starting with the N terminus. (C) A sketch illustrating the maintenance of WUS levels and spatial patterning, through DNA-dependent homodimerization, nuclear-cytoplasmic partitioning, and WUS protein destabilization represented on the inflorescence meristem cell layers. WUS is synthesized in a few cells of the rib meristem and migrates into adjacent cells, where it accumulates at a lower level in the nuclei of cells in the L1 and the L2 layers compared with the inner layers. Our analysis suggests a relatively higher nuclear export (indicated by the strength of magenta colored arrows) and a lower nuclear retention of WUS, which could be due to the lower affinity to the DNA (indicated by the strength of the white arrows) and a lower dimerization propensity (indicated by the strength of the white arrows with black outline) in the top layers than in the inner layers. WUS could be destabilized in outer layers (indicated by red arrows). We hypothesize that this destabilizing factor may be WUS-dependent (represented by the blue dashed arrows), which needs to be tested in future studies.