Abstract

Background and Objectives

Opioid users in treatment are at high risk of relapse and overdose, making them an important target for efforts to reduce opioid overdose mortality. Overdose Education (OE) is one such intervention, and this study tests the effectiveness of OE in a community substance use disorder treatment program.

Methods

Opioid users were recruited from a community treatment center for the study. The Opioid Overdose Knowledge Scale (OOKS) was administered before and after an educational intervention (small group lecture, slideshow, and handout based on previously published content) to assess knowledge of the risks, signs, and actions associated with opioid overdose, including use of naloxone. Additional survey questions assessed naloxone access, naloxone education, and overdose experiences at treatment and 3‐month follow‐up. Subjects (n = 43) were 28% female and had a mean age of 31 years. OOKS scores were compared at pre‐intervention, post‐intervention, and follow‐up, and results were also compared with a historical non‐intervention control group (n = 14).

Results

Total score on the OOKS increased significantly from pre‐ to post‐education, and improvement was maintained at follow‐up (p < .0001). OOKS subdomains of actions and naloxone use also had significant increases (p < .0001). Four subjects reported possessing naloxone in the past, and only one subject who did not already have naloxone at the time of treatment had obtained it at follow‐up.

Conclusions and Scientific Significance

Education about opioid overdose and naloxone use in a community treatment program increases overdose knowledge, providing support for the idea of making OE a routine part of substance use disorder treatment. However, the rate of follow through on accessing naloxone was low with this education‐only intervention. (Am J Addict 2016;25:221–226)

INTRODUCTION

Overdose has become the leading cause of death by injury in the US, responsible for tens of thousands of preventable deaths each year.1 This rapid change is primarily due to the dramatic increase in prescription opioid availability and misuse over the past 20 years.2, 3 Opioids are the most common drug type involved in unintentional overdose and represent a critical target for overdose prevention strategies.4

Numerous strategies have been implemented to respond to the growth in opioid overdose deaths—educating health care providers and the public, prescription monitoring programs, prescription drug take‐back programs, and overdose prevention education and naloxone distribution (OEND) programs.5 Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that reverses overdoses by quickly displacing opioid agonists from the receptors and is the treatment of choice for opioid overdose. Recently there has been increased interest in expanding access to naloxone to potential overdose bystanders so that it can be administered quickly when an overdose occurs.6 Initial naloxone distribution efforts occurred primarily through needle exchanges and other urban community outreach programs,7, 8 but lately naloxone kits have been increasingly distributed to emergency responders,9, 10 known drug users and their families,11 and others.12 Specific efforts have also evaluated distribution through pharmacies4 and Emergency Departments.13

One high‐risk population that is often overlooked is opioid using patients in treatment. Risk of overdose death is higher among people who use opioids upon treatment completion, presumably due to reduced tolerance during a sustained period of drug abstinence.14 As a result, providing overdose prevention in a treatment setting targets a population especially susceptible to overdose death.

Historically, many treatment programs have been reluctant to provide naloxone education and distribution because of the perception that it contradicts the emphasis on drug abstinence, a main focus in most treatment settings.5, 15 In addition, prescribing and/or distribution of naloxone to patients within the treatment program itself raises further challenges due to cost, legal and regulatory requirements regarding prescribing and medication distribution, and physician attitudes and knowledge gaps about prescribing.16, 17 Thus, although local (Illinois) laws at the time of the study offered partial legal protection for prescribing and dispensing naloxone,18 significant barriers remained to implementing either strategy. However, providing overdose education alone, without any naloxone prescribing or distribution, presents fewer logistical and legal barriers. This can be done by providing education about opioid overdose, including proper use of naloxone, along with referrals to outside resources for access to naloxone, providing nearby easy access to naloxone overdose kits for free or low cost (depending on the location chosen by the patient). Thus, instituting routine overdose education in treatment settings provides a relatively simple way of addressing the growing opioid overdose problem in a very high‐risk population.

Many studies have evaluated the effects that overdose prevention and response training programs have on the knowledge and behaviors of people who use opioids.19, 20, 21, 22 Most studies occurred in community outreach programs or similar settings, but only one case report has been published about use in a standard treatment program setting.5

The purpose of this study is to evaluate an overdose education intervention in a treatment program setting, testing the hypothesis that education during the treatment program will improve patients’ knowledge of opioid overdose signs and response strategies, including use of naloxone, and result in increased access to naloxone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were selected from patient admissions with opioid use at a community addiction treatment center for the 1 month preceding and 12 months following implementation of a new naloxone educational program, which became a standard part of the treatment program curriculum for all patients using opioids. Patients with an opioid use disorder diagnosis were invited to participate in the study and were enrolled after giving informed consent. The only exclusion criterion was moderate to severe cognitive deficits. Participants were ages 18–61 and 28% female (see Table 1). This study was approved by the local hospital institutional review board, was operated under a NIDA Certificate of Confidentiality, and was registered at clinicaltrials.gov. All subjects provided informed consent before participation in the study.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 57 patients, by group a

| Demographic characteristic | Control n = 14 | Int. n = 43 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (yrs) | 26.1 | 30.6 | .19 |

| Gender | |||

| % Female | 21.4 | 27.9 | .63 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| % Caucasian | 92.9 | 88.4 | .57 |

Comparisons between groups were made using independent samples t‐test and χ2 tests for frequency data.

Study Procedures and Naloxone Program Description

Prior to implementation of the new educational intervention, researchers assessed the knowledge of subjects (N = 14) using the Opioid Overdose Knowledge Scale (OOKS),23 which served as a non‐interventional control group. Although they did not receive the new formal educational module, these patients did receive printed information about where they could obtain naloxone overdose kits. This group was retested at 3 month follow up. All subjects were offered a $5 gift card as an incentive for completing the follow up session.

Researchers then began delivering an educational session for opioid using patients in the suburban, adult outpatient programs (intensive outpatient program or IOP and partial hospitalization program or PHP). The 4‐week program consists of predominantly group‐based sessions including CBT, education, and 12‐step facilitation, as well as family therapy session, psychiatrist sessions, and pharmacotherapy (including buprenorphine/naloxone). The new educational session content was adapted from the New York State Department of Health's Opioid Overdose Prevention Guidelines for Training Responders 24 by summarizing it in a 23‐slide slideshow and adding pictures. The session follows a group format with lecture, slideshow, and handout and provides detailed information on recognizing signs of opioid overdose and use of naloxone. Patients were able to ask questions during and after the presentation, and the entire session was 30–45 min. Sessions were conducted by a post‐doctoral clinical staff member (author JR) for the first 4 months of the study and then by a different pre‐doctoral clinical staff member. Both had supervision by author DL when starting the training sessions and as needed for later sessions. At the end of the session, patients were then given specific instructions verbally and in writing about obtaining naloxone kits from local providers and distribution sites.

Every patient with an opioid use disorder was asked to complete this educational session, and subjects recruited from this population agreed to complete several questionnaires. The OOKS was delivered to them three times: (1) immediately prior to the educational intervention; (2) immediately after the educational intervention; and (3) at follow‐up (mean follow up at 94 d). Subjects in the control group received the OOKS once during treatment and once at follow‐up. In addition, subjects completed a separate survey about overdose and naloxone once before the educational session and once during the follow up session.

Measures

The Opioid Overdose Knowledge Scale (OOKS23;) is an empirically validated questionnaire that surveys the subjects’ knowledge of the risks, signs, and actions associated with opioid overdose, as well as the appropriate use of naloxone.

That is, this 45‐item check‐list measures understanding of various aspects of opioid overdose, identified as four subdomains: (1) Risks—overdose risk factors (eg, larger doses, using an opioid after detoxification treatment, etc.); (2) Signs—overdose signs (eg, blue lips, unresponsive, etc.); (3) Actions—life saving actions one may take (eg, clearing the victim's airway, mouth‐to‐mouth resuscitation, call 911, etc.); and (4) Naloxone Use—the appropriate use of naloxone (eg, administration, duration, etc.). Initial psychometric research23 has indicated that this is a suitable way to evaluate naloxone training for overdose bystanders.

A separate naloxone survey was developed for this study with additional questions specific to naloxone use, access, and related behaviors. Dichotomous data were collected to measure witnessing overdoses, overdose education experience, naloxone access, and naloxone use.

Analysis

The primary outcome analyses of the OOKS total and subdomain data were evaluated using linear mixed model analysis with time as a factor. Comparison with the historical control group was made using linear mixed model analysis with group and time as factors. Demographics variables were compared with unpaired t‐tests (continuous data) and χ2 tests (categorical data). Comparison of dichotomous data on the naloxone questionnaire was made using McNemar's test. Alpha was set at .05 (two‐tailed) for all statistical analyses, which were conducted using SPSS 23 statistical software.

RESULTS

OOKS

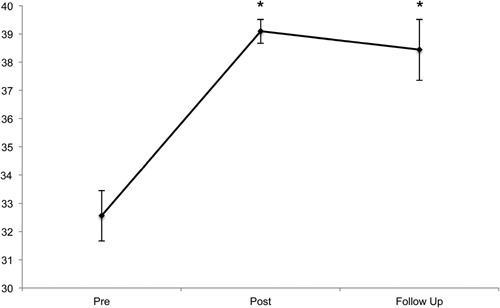

Figure 1 shows the significant improvement in knowledge scores from the OOKS following the education from 32.6 to 39.1 (p < .0001), which was mostly retained at the follow‐up time point (total score of 38.4). The OOKS subdomains Actions and Naloxone Use followed a similar pattern (p < .0001). For the other two subdomains, Risks and Signs, changes were not statistically significant but trended toward significance (p < .10).

Figure 1.

OOKS total score across time for intervention group, *p < .0001.

Twenty‐two total subjects completed follow up questionnaires, which was 39% of the enrolled subjects (37% for treatment group and 42% for control group).

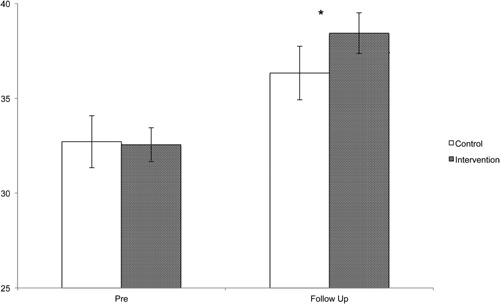

Comparison With Historical Control Group

In the analysis of the OOKS Total score, there was a significant group × time effect (p < .05) reflecting the greater knowledge improvement in the intervention group after receiving the naloxone education (increase from 32.6 to 38.4) (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the control group also showed an improvement at follow up, increasing from 32.7 to 36.3 (there was a significant overall time effect with p < .005). Within the control group alone, mean scores improved not only for Total OOKS but also for each subdomain except for Signs.

Figure 2.

OOKS total score intervention versus control, *p < .05 group × time effect.

OOKS subdomain analyses revealed consistently significant time main effects for each subdomain, but only the Naloxone Use subdomain produced a significant group × time effect (p < .05), indicating the greater score increase in the intervention group. Thus, the intervention group showed greater improvement in the OOKS total score and the Naloxone Use subdomain score in comparison to the control group. However, post‐hoc comparisons of the intervention versus control follow‐up scores for OOKS Total and Naloxone Use were not significant.

Naloxone Questionnaire

Four subjects (7% of sample) reported possessing naloxone in the past. This included one of the control subjects (7%) and three intervention subjects (7%). Only one subject who did not already have naloxone at the time of treatment obtained it during follow up, and an additional one subject newly obtained access to naloxone at their location of use. Both these subjects were in the intervention group, and no subjects in the control group had newly obtained access to naloxone at follow up. There was no significant difference in number of subjects possessing naloxone after the intervention (Table 2).

Table 2.

Naloxone survey, intervention effect a

| Survey item | Pre‐Ed. n = 43 | Follow‐up n = 16 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Received prior education on opioid overdose signs | 37.2 | 100 | <.01 |

| Received prior education on naloxone use | 18.6 | 100 | <.01 |

| Possess naloxone in home | 7.0 | 12.5 | 1.0 |

| Naloxone access at place of use | 2.3 | 12.5 | .5 |

| Used naloxone on another past year | 0 | 0 |

Comparisons between groups were made using McNemar's test for dichotomous data, percentages shown in table. Bold p‐values indicate statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that the educational group session was effective at increasing opioid overdose and naloxone knowledge among treatment‐seeking opioid use disorder patients, a population at high risk of opioid overdose death.

The instrument used for assessing knowledge, the OOKS, has been validated and used in previous research for similar evaluations. The overall total score increased after the educational group, reflecting the hypothesized improvement in knowledge about opioid overdose. Two of the subscores, Actions and Naloxone Use, also had a significant score increase following the educational group. The lack of a significant increase in the two remaining subdomains, Risks and Signs, may be due to lack of sufficient power, especially since there was a trend toward significance. It may also reflect relative deficiencies in the education in these knowledge areas, providing an opportunity for improvement.

Although retention at follow up was limited (38%), enough subjects responded to demonstrate good knowledge retention at the follow‐up assessment. Interestingly, the control group also showed substantial knowledge gains at the follow‐up time point. The treatment group had significantly greater knowledge improvement than controls, showing that the intervention was indeed effective. However, it is interesting that knowledge improved so much in the control group without specific intervention. On possible explanation is that the study and questionnaire process itself may have led to some immediate or delayed knowledge acquisition. In addition, although controls did not receive the educational module, they were already receiving some unstructured naloxone education from staff as well as printed information about naloxone distribution sites.

It is hard to know how much the knowledge improvement can or will translate into lives saved from overdose, either by the study subjects themselves or in others that they may witness. However, having access to naloxone is a critical, concrete step that will significantly improve the chance of saving lives when witnessing an overdose. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the impact of the educational program on access to naloxone, especially since there was no direct distribution of naloxone itself to the participants.

There was no increase in naloxone access reported following this educational intervention. Only one subject newly obtained naloxone after the intervention, as of the time of the follow up assessment. The educational intervention clearly improved knowledge, but it did not yield any measurable improvement in naloxone access. This type of intervention, education without direct distribution of naloxone, may not improve the practical access to naloxone needed to help reduce opioid overdose mortality.

One important limitation of the study was the lack of randomization. A pre‐intervention historical cohort was used as a control group without any random assignment or matching. Although the demographic variables were similar in the two groups, this type of design is particularly susceptible to cohort effects that could have introduced unanticipated influences on outcomes apart from the intervention itself. Additional research could be designed so that participants are randomly assigned to groups in a prospective study. Such methods would help further clarify the effectiveness of similar interventions in community treatment centers. One additional limitation is the relatively low follow up rate, which increases the risk of biased follow up data. Second, the time of the follow up was highly varied with a mean time to follow up much longer than the 1‐month goal. This was due in part to delays in hearing back from subjects to conduct the follow up interviews, as well as delays by staff in making the initial and follow‐up contact attempts. However, this additional delay in the follow up time would be expected to reduce retention of knowledge gained from the intervention and bias results away from the observed effect.

Implementation of opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) programs has grown in the last several years because of increasing opioid overdose mortality. In spite of these efforts, several important barriers continue to limit naloxone use—its status as a prescription medication, cost, negative attitudes toward the drug, and a variety of other legal and regulatory issues. To address some of these barriers, since 2001 a total of 43 states have now passed some type of law aimed at increasing naloxone access and/or use.16, 18 Such laws typically provide liability protection for those who prescribe, dispense, or administer naloxone. Many laws also improve access by specifically allowing third party prescriptions (ie, prescriptions to a layperson for use on someone else) and standing order prescriptions (ie, allowing the medication to be prescribed to a person that has not been examined directly). Thirty‐four states have also passed laws to encourage opioid overdose bystanders (ie, Good Samaritans) to seek the help of first responders by providing immunity from criminal prosecution for drug‐related offenses.16, 18

However, treatment providers have been slow to add these strategies. One common barrier is the idea that OEND contradicts the goals of treatment, which typically involve abstinence from substances of abuse. However, the dramatic rise in opioid use and opioid overdose deaths has caused many to reassess these longstanding views. In spite of this, many barriers continue in treatment settings. First, the cost of the medication has increased significantly in recent years, which may pose barriers both for program distribution of naloxone as well as patient purchase at a pharmacy. Second, many programs have internal regulations limiting distribution of medications or standing order prescriptions, especially in larger health systems. Finally, attitudes of prescribers and other staff often continue to limit prescribing. Over time, more treatment programs have begun to offer education and distribution of naloxone, although no studies have been published on findings in this population.

Treatment seekers are an important group to target with this intervention for several reasons. First, because of their significant opioid use disorders they are at high risk for relapse back to opioid use. Second, these patients are known to be at especially high risk for overdose death after completing treatment, most likely because of the reduced opioid tolerance resulting from their sustained drug abstinence during treatment. Finally, this group is also very likely to witness overdoses occur in others because they often use together with others.

Future directions of this research will include evaluation of other methods to try to improve patient access to naloxone such as increased access to prescriptions and possibly direct distribution of naloxone within the treatment program.

In summary, this study in a community treatment program demonstrates the effectiveness of an educational intervention on improving patient knowledge of opioid overdose and naloxone. The intervention had limited effect on improving patient access to naloxone, suggesting that education alone, in the absence of naloxone distribution, may not be optimal for reducing opioid overdose mortality in this high‐risk population. Accumulating data shows the potential for overdose education and naloxone distribution to reduce overdose mortality, and this study provides additional support for the idea of making this a standard part of treatment for opioid use disorders.

DL and JR received financial support from Linden Oaks.

We wish to thank Beth Sack, Ashley Forrest, Laura Daniels, and the rest of the staff at the Linden Oaks Addiction Treatment Programs, whose efforts have made the education program successful. Preliminary results of this study were presented in poster form at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web‐based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). [accessed October 5, 2015] http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/leading_causes_death.html

- 2. Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008; 300:2613–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6043a4.htm?s_cid=mm6043a4_w#fig2. Accessed August 17, 2015.

- 4. Green TC, Dauria EF, Bratberg J, et al. Orienting patients to greater opioid safety: Models of community pharmacy‐based naloxone. Harm Reduct J. 2015; 12:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilder CM, Brason FW, 2nd , Clark AK, et al. Development and implementation of an opioid overdose prevention program within a preexisting substance use disorders treatment center. J Addict Med. 2014; 8:164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wheeler E, Jones T, Gilbert M, et al. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons—United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014; 64:631–635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maxwell S, Bigg D, Stanczykiewicz K, et al. Prescribing naloxone to actively injecting heroin users: A program to reduce heroin overdose deaths. J Addict Dis. 2006; 25:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doe‐Simkins M, Walley AY, Epstein A, et al. Saved by the nose: Bystander‐administered intranasal naloxone hydrochloride for opioid overdose. Am J Public Health. 2009; 99:788–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davis CS, Southwell JK, Niehaus VR, et al. Emergency medical services naloxone access: A national systematic legal review. Acad Emerg Med. 2014; 21:1173–1177. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davis CS, Ruiz S, Glynn P, et al. Expanded access to naloxone among firefighters, police officers, and emergency medical technicians in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health. 2014; 104:e7–e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bagley S M, Peterson J, Cheng D M, et al. Overdose education and naloxone rescue kits for family members of individuals who use opioids: Characteristics, motivations, and naloxone use. Subst Abus. 2015; 36:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Green TC, Bowman SE, Zaller ND, et al. Barriers to medical provider support for prescription naloxone as overdose antidote for lay responders. Subst Use Misuse. 2013; 48:558–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dwyer K, Walley AY, Langlois BK, et al. Opioid education and nasal naloxone rescue kits in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015; 16:381–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davoli M, Bargagli AM, Perucci CA, et al. Risk of fatal overdose during and after specialist drug treatment: The VEdeTTE study, a national multi‐site prospective cohort study. Addiction. 2007; 102:1954–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Green TC, Bowman SE, Zaller ND, et al. Barriers to medical provider support for prescription naloxone as overdose antidote for lay responders. Subst Use Misuse. 2013; 48:558–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis CS, Carr D. Legal changes to increase access to naloxone for opioid overdose reversal in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015; 157:112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beletsky L, Ruthazer R, Macalino GE, et al. Physicians' knowledge of and willingness to prescribe naloxone to reverse accidental opiate overdose: Challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2007; 84:126–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Network for Public Health Law. Legal interventions to reduce overdose mortality: naloxone access and overdose good samaritan laws. Last updated September, 2015. [accessed January 21, 2016] https://www.networkforphl.org/_asset/qz5pvn/network‐naloxone‐10‐4.pdf

- 19. Green TC, Heimer R, Grau LE. Distinguishing signs of opioid overdose and indication for naloxone: An evaluation of six overdose training and naloxone distribution programs in the United States. Addiction. 2008; 103:979–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tobin KE, Sherman SG, Beilenson P, et al. Evaluation of the staying alive programme: Training injection drug users to properly administer naloxone and save lives. Int J Drug Policy. 2009; 20:131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wagner KD, Valente TW, Casanova M, et al. Evaluation of an overdose prevention and response training programme for injection drug users in the Skid Row area of Los Angeles, CA. Int J Drug Policy. 2010; 21:186–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Walley AY, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: Interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013; 346:f174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Williams AV, Strang J, Marsden J. Development of opioid overdose knowledge (OOKS) and attitudes (OOAS) scales for take‐home naloxone training evaluation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013; 132:383–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.New York State Department of Health. Opioid Overdose Prevention: Guidelines for Training Responders. Oct 2006. https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/providers/prevention/harm_reduction/opioidprevention/programs/guidelines/docs/training_repsonders.pdf