Abstract

Objectives

To introduce a multi-site assessment of oral health literacy and to describe preliminary analyses of the relationships between health literacy and selected oral health outcomes within the context of a comprehensive conceptual model.

Methods

Data for this analysis came from the Multi-Site Oral Health Literacy Research Study (MOHLRS), a federally-funded investigation of health literacy and oral health. MOHLRS consisted of a broad survey, including several health literacy assessments, and measures of attitudes, knowledge, and other factors. The survey was administered to 922 initial care-seeking adult patients presenting to university-based dental clinics in California and Maryland. For this descriptive analysis, confidence filling out forms, word recognition, and reading comprehension comprised the health literacy assessments. Dental visits, oral health functioning, and dental self-efficacy were the outcomes.

Results

Overall, up to 21% of participants reported having difficulties with practical health literacy tasks. After controlling for sociodemographic confounders, no health literacy assessment was associated with dental visits or dental caries self-efficacy. However, confidence filling out forms and word recognition were each associated with oral health functioning and periodontal disease self-efficacy.

Conclusions

Our analysis showed that dental school patients exhibit a range of health literacy abilities. It also revealed that the relationship between health literacy and oral health is not straightforward, depending on patient characteristics and the unique circumstances of the encounter. We anticipate future analyses of MOHLRS data will answer questions about the role that health literacy and various mediating factors play in explaining oral health disparities.

INTRODUCTION

Health literacy is commonly defined as, “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (1). The 2008 Calgary Charter on Health Literacy (2) adds that health literacy is a resource, encompassing a range of skills, including reading, writing, listening, speaking, critical analysis, and interacting with the healthcare system. According to the most recent national assessment of health literacy (3), 36% of American adults do not have the skills necessary to effectively manage their health and navigate the healthcare system.

Investigations of health literacy and medical outcomes show that individuals with limited health literacy skills have lower medication adherence (4), less knowledge of disease management (5, 6), poorer health status (7), and higher medical expenses (8, 9). Several conceptual frameworks explain the links between health literacy and these adverse outcomes. Nielsen-Bohlman and colleagues (10) hypothesize that health literacy is related to a person’s ability to read and that this skill, in turn, influences health outcomes, directly. Reflecting a more global framework, Paasche-Orlow and Wolf (11) propose that health literacy is influenced by several factors beyond reading comprehension, including demographics, social support, language, and physical/mental capacity. They also argue health literacy does not directly influence health outcomes. Instead, they hypothesize that health literacy influences health through three intermediate pathways: access to and utilization of health care services, provider-patient interaction, and self-care. Osborn and colleagues (12) provide empirical evidence for this pathway-driven relationship. They show that health literacy influences health and illness by working through factors such as conceptual knowledge, self-efficacy, and self-care behaviors. Sorenson and colleagues (13) add that health literacy demands may be situation specific and are likely to change over the life course.

While the literature is replete with studies of health literacy and medical outcomes, links between health literacy and oral health have received less attention. Given that the medical and oral healthcare systems share many similarities, health literacy research in dentistry has borrowed methods and models from research in medicine. However, there are many unique aspects of the dental care system that demand special attention in oral health literacy research; namely the relative scarcity of safety-net resources for adults, discipline-specific vocabulary, social expectations about esthetics, and the acute nature of dental pain, among others. In 2012, Lee and colleagues (14) offered a simplified conceptual model linking health literacy with self-reported oral health status, incorporating some of the mediating factors identified by Osborn and colleagues (12). Still, more exploratory work needs to be conducted to understand the various ways that health literacy and oral health are inter-connected.

The purposes of this analysis are to introduce the methods used in a federally-funded, multi-site assessment of oral health literacy and to describe preliminary analyses of the hypothesis-driven relationships between health literacy and selected oral health measures within the context of a new conceptual framework.

METHODS

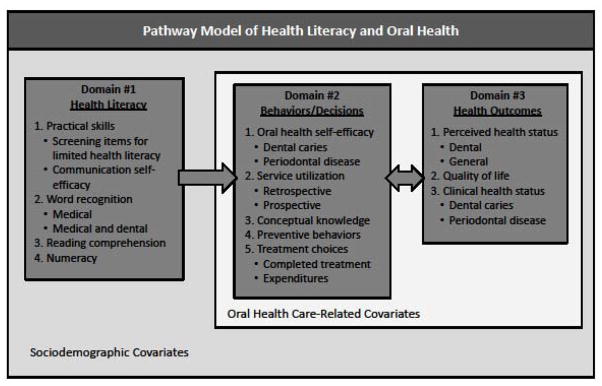

This section describes the Multi-Site Oral Health Literacy Research Study (MOHLRS), an investigation of the relationships between health literacy and oral health conducted among dental school patients in urban, university-based dental clinics in California and Maryland. Figure 1 shows the pathway model linking health literacy with oral health that was used as the conceptual framework for this investigation. The model includes three domains: Health Literacy (Domain #1), Behaviors/Decisions (Domain #2), and Health Outcomes (Domain #3), influenced by selected oral health-related and socioeconomic status (SES) covariates.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework

Sample recruitment

The target population for the MOHLRS included English-speaking, initial care-seeking, adult patients presenting to the screening, oral surgery, and urgent care clinics affiliated with schools of dentistry at The University of Maryland and The University of California Los Angeles (UCLA). “Initial care-seeking” patients were defined as either new patients to the clinics or patients who had no more than four total visits to the respective sites during the preceding five years. Participants were recruited from the dental clinic waiting rooms using a variety of methods, including printed cards and posters, advertisements displayed on clinic television monitors, and personal encounters with trained members of the research team. Patients who wished to be involved could participate immediately or were given the option to schedule data collection at another time (especially important for individuals who were in pain or distress during the initial visit). Patients who did not speak English, who had notable vision and/or hearing disabilities, and who were trained or employed as nurses, physicians, or dental personnel were not eligible to participate.

Survey development and administration

During the initial stages of survey development, the research team searched the literature for existing survey instruments and/or individual survey items related to health literacy, health behaviors, and health status. For topic areas that lacked existing instruments, research team members developed individual items or composite measures that would meet the specific needs of the project. Team members relied heavily on the conceptual model to guide the selection of existing instruments and development of new or modified assessments. Subsequent qualitative pilot testing (conducted between Fall 2011 and Spring 2012) involved two phases. The first phase assessed wording and formatting of survey items that were not already part of an existing instrument. The second phase was designed to assess respondent burden, defined as the amount of time and/or cognitive effort required to complete the entire survey instrument.

Given that the study was likely to include participants with a range of literacy skills, the research team developed the survey so that an individual’s ability to read would be less likely to directly influence his or her responses to non-literacy-type questions (such as one’s knowledge, attitudes, health behaviors, etc.). In order to accomplish this objective, the research team designed the consent forms and each section of the survey to be read aloud to participants. In addition, survey instructions and transitional text were written at a reading level of 4th to 6th grade. Response categories for selected items were also reproduced onto Microsoft© PowerPoint slides and loaded onto a tablet device, allowing participants to see response choices at the same time that interviewers read them aloud. The entire survey took approximately 40 minutes. Recruitment and data collection for the final survey began in May of 2012 and proceeded through September of 2014.

Upon completion of the survey, responses were entered into a secure, Internet-based electronic database (Qualtrics© software program). Participants received either a cash payment or a cash payment with parking voucher (value dependent on recruitment site). Research methods were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Maryland, Baltimore; University of California, Los Angeles; and University of Baltimore.

Clinical chart reviews

The participant’s written consent allowed trained members of our research team to access his or her clinical chart for a period of up to two years beyond the initial interview. Clinical assessments included a variety of dental caries and periodontal disease assessments. Dental charts were also used to record hypertension, diabetes status, smoking status, dental visits, treatment services, and expenditures.

Survey responses and chart data were merged into an analytical file by means of a unique identifier assigned to each participant. Once survey and chart data were combined, all personal identifying information was removed from the analytical file to maintain participant anonymity. The SAS© statistical software program for Windows (Version 9.3) was used for data cleaning and analysis.

Domain-specific variables

Figure 1 lists the study variables that were associated with the project. Domain #1 (Health Literacy) contained a mix of health literacy measures. The Practical Skills category included two different variables that were derived from existing instruments; a 3-item screening tool for determining functional/task-based health literacy (15) and a 4-item measure of communication self-efficacy (16). The Word Recognition category also included two variables; the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) (17) and the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine and Dentistry (REALM-D) (18). The Reading Comprehension category included the short version of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (Short-TOFHLA) (19). The Numeracy category included the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) (20), a 6-item measure of an individual’s ability to employ quantitative reasoning in a health-related context.

Domain #2 (Behaviors/Decisions) contained several measures that were hypothesized to be mediators in the pathway(s) between health literacy (Domain #1) and oral health (Domain #3). The Self-Efficacy category included two items that reflected an individual’s confidence in knowing how to prevent dental caries and periodontal disease, respectively. The Service Utilization category included two self-reported measures; lifetime use of non-dental healthcare services (e.g., emergency department, physician’s office) for a dental problem, as well as self-reported dental visits. The Conceptual Knowledge category included two different variables. The first one was the Comprehensive Measure of Oral Health Knowledge (CMOHK) (21), a 23-item assessment of basic oral health knowledge and disease prevention. The second one was a new, 5-item survey assessing knowledge of dental treatment costs and safety-net insurance coverage. The Preventive Behaviors category reflected an individual’s proclivity for seeking preventive health services and adopting healthful activities, including items that assessed tooth brushing, exercise, and vaccinations. One additional topic in Domain #2 represented two different prospective measures. The Treatment Choices category measured the provision of dental services and their associated costs during a 2-year follow-up period. For patients who did not receive services during the entire follow-up period, our research team determined whether existing visits were for acute issues (such as extractions due to pain) or for specific, limited types of services (such as the extraction of impacted third molars).

Domain #3 (Health Outcomes) included several categories of variables that reflected both self-reported and objective health status. The Perceived Health Status category consisted of two Likert-scale items borrowed from the National Health Interview Survey (22); one assessing self-reported oral health status and the other general health status. The Quality of Life category was represented by the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) (23), a validated measure of oral health functioning among adults. The Clinical Health Status category included three variables that measured objective, clinically-determined oral health. : number of teeth present/missing, lifetime dental caries history, and unmet dental caries treatment need. Lifetime dental caries history was described either as the sum of all decayed, missing, and filled permanent teeth (DMFT) or as a dichotomous outcome (DMFT=0 or DMFT>0). Unmet dental caries treatment need was described as either the sum of all decayed teeth (DT) or as the percentage of the DMFT due to untreated dental caries (%DT/DMFT).

The two remaining categories of variables included potential confounders of the relationship between health literacy and oral health. The Oral Health Care-Related Covariates category consisted of four topic areas. The Health Beliefs/Attitudes area included 11 Likert-scale items selected from the Florida Dental Care Study (24) and 4 Likert-scale questions regarding health values (25). The Social Support area included 5 Likert-scale questions concerning functional- and community-level assistance (26). The Health Locus of Control component contained 6 Likert-scale questions assessing how individuals related to being ill (27). The Sources of Information area consisted of items from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (28) that asked about where individuals obtained health-related information; that is, from either written or broadcast sources, the Internet, or from other persons.

The Sociodemographic Covariates category included several variables: recruitment site, age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, annual household income, languages spoken, marital status, and dental insurance status. The languages spoken variable represented a combination of two attributes; languages spoken currently and the primary language spoken as a child.

Methods used in the present analysis

In order to demonstrate the utility of our conceptual model and conduct initial analyses, we selected a variety of variables for the present report, including three commonly used health literacy measures [the screening tool for determining limited health literacy (15), the REALM (17), and the Short-TOFHLA (19)] from Domain #1, two oral health variables from Domain #2 (dental care utilization and self-efficacy), and one oral health measure from Domain #3 (GOHAI) (23). Given our conceptual framework, we hypothesized that limited health literacy would be associated with infrequent dental visits, low self-efficacy, and unfavorable oral health functioning, after controlling for relevant covariates.

A total of 922 individuals were recruited into the MOHLRS project. This group is described in Table 1 to serve as a reference for future publications. Note that any missing sociodemographic data in the dataset [education level (7 missing observations), languages spoken (8 missing observations), marital status (7 missing observations), and dental insurance status (7 missing observations)] were imputed with IVEware statistical software (Version 0.2; University of Michigan 2012), developed by programmers with The University of Michigan Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research. This software program employed a Sequential Regression Multivariate Imputation method (SRMI) (A) whereby missing values were replaced using a chained regression model that relied on all other variables present in the model as predictors, in a cyclic process (in our case, with eight iterations). The imputation software program was designed to account for missing data across a range of variable types that exhibit either monotone or arbitrary patterns of missing data. It was also developed to use an imputation approach that can be finely tuned, on a variable by variable basis. Statistical modeling has revealed that the IVEware program produces parameter estimates and confidence intervals that are comparable to a fully Bayesian method (A).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics, by recruitment site (n=922)

| Characteristic | Maryland | California | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (column percentage) | |||

| Overall | 456 (100.0) | 466 (100.0) | 922 (100.0) |

| Age | |||

| 18–24 | 30 (6.6) | 44 (9.4) | 74 (8.0) |

| 25–44 years | 165 (36.2) | 161 (34.5) | 326 (35.4) |

| 45–64 years | 215 (47.1) | 187 (40.2) | 402 (43.6) |

| 65 years or greater | 46 (10.1) | 74 (15.9) | 120 (13.0) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 210 (46.1) | 240 (51.5) | 450 (48.8) |

| Female | 246 (53.9) | 226 (48.5) | 472 (51.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 126 (27.6) | 227 (48.7) | 353 (38.3) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 274 (60.1) | 60 (12.9) | 334 (36.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 5 (1.1) | 34 (7.3) | 39 (4.2) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 32 (7.0) | 39 (8.4) | 71 (7.7) |

| Hispanic | 19 (4.2) | 106 (22.7) | 125 (13.6) |

| Multiple languages spoken now / languages spoken as a child | |||

| No / English only | 388 (85.1) | 218 (46.8) | 606 (65.8) |

| Yes / English only | 36 (7.9) | 74 (15.9) | 110 (11.9) |

| Yes / English and other | 8 (1.7) | 77 (16.5) | 85 (9.2) |

| Yes / Other than English | 22 (5.3) | 97 (20.8) | 121 (13.1) |

| Education level | |||

| Less than 12 years | 54 (11.8) | 19 (4.1) | 73 (7.9) |

| 12 years of GED | 167 (36.6) | 65 (14.0) | 232 (25.2) |

| Some college | 132 (29.0) | 153 (32.8) | 285 (30.9) |

| College graduate | 103 (22.6) | 229 (49.1) | 332 (36.0) |

| Annual household income | |||

| $0–$22,000 | 130 (28.5) | 165 (35.4) | 295 (32.0) |

| $22,001–$44,000 | 155 (34.0) | 115 (24.7) | 270 (29.3) |

| $44,001 or greater | 119 (26.1) | 134 (28.7) | 253 (27.4) |

| Undetermined | 52 (11.4) | 52 (11.2) | 104 (11.3) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married or co-habitating | 167 (36.6) | 164 (35.2) | 331 (35.9) |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 117 (25.7) | 111 (23.8) | 228 (24.7) |

| Never married | 172 (37.7) | 191 (41.0) | 363 (39.4) |

| Private dental insurance | |||

| Yes | 226 (49.6) | 125 (26.8) | 351 (38.1) |

| No | 230 (50.4) | 341 (73.2) | 571 (61.9) |

Note: Statistically significant associations (P<0.05) listed in bold

All of the sociodemographic variables in the current analysis were included in the imputation so that imputed findings would reflect the entire dataset and could be used in subsequent analyses to describe the final, overall sample. None of the sociodemographic variables had more than 1% item non-response and/or missing values.

In the present report, the sample used to test the associations between health literacy and oral health included only 914 individuals because 8 of the 922 participants were excluded for having 2+ missing responses (greater than 10% of items in the scale) to the 12 GOHAI survey items. Multiple imputation was also used to estimate any missing values in the present hypothesis-driven analysis; both for the oral health outcome measures [dental visits (2 missing observations), dental caries self-efficacy (3 missing observations), and periodontal disease self-efficacy (5 missing observations), as well as for the GOHAI variable (34 missing observations)]. The previously described multivariate imputation method (A) was also used for this stage of the analysis; all of the sociodemographic and outcome variables were included in the imputation process. Of the outcome variables included in the imputation analysis, the GOHAI variable had the highest level of missing data but it was still only 3.7%.

Dental care utilization was divided into two time periods: 1) a visit in the last year, and 2) a visit more than one year ago, or never. The dental caries and periodontal disease self-efficacy outcomes were also dichotomized, based on how certain the participant knew what was needed to prevent each disease: 1) high efficacy (representing responses “very sure” and “somewhat sure”), and 2) low efficacy (representing responses “somewhat unsure” and “very unsure”). The oral health functioning outcome (GOHAI) was split into “favorable” and “unfavorable” categories at the median value. Established cut-offs were used for coding the health literacy measures (15, 17, 19). However, scores for the two lowest categories of the REALM and Short-TOFHLA, respectively, were combined due to small cells.

Bivariate associations between discrete variables were assessed by chi-squared tests (or Fisher exact tests, as required by small cell sizes). Logistic regression and multiple logistic regression were used to test relationships against the main outcome measures (dental care utilization, oral health functioning, and self-efficacy). Multivariable models controlled for recruitment site, age, gender, race/ethnicity, multiple languages spoken, education level, annual household income, marital status, and dental insurance status. These covariates were selected because of their inclusion in the conceptual model, their relationship to sample recruitment, and their reflection of sociodemographic characteristics known to be associated with health literacy and dental care utilization (3, B). An alpha value of 5% was used as the cut-off for statistical significance in all assessments.

RESULTS

Of the 922 participants in the MOHLRS (Table 1), 466 (50.5%) were recruited from the California site and 456 (49.5%) from the Maryland site. The majority of study participants were women (51.2%), non-Hispanic white (38.3%), and 45–64 years of age (43.6%). In terms of SES, 33.1% of participants had no more than a high school diploma; 32.0% earned up to $22,000 annually; 39.4% were never married; and 61.9% had no form of dental insurance coverage. Three hundred sixteen (33.9%) participants reported speaking multiple languages at the time of the survey and 121 of the 316 individuals (38.3%) reported speaking a primary language other than English as a child.

Table 1 describes the total recruited sample, stratified by site. Recruits from California were significantly more likely to be seniors (15.9% vs. 10.1%; P=0.01) and Hispanic (22.7% vs. 4.2%; P<0.01). Participants from Maryland were significantly more likely to be non-Hispanic black (60.1% vs. 12.9%; P<0.01), speak only English (85.1% vs. 46.8%; P<0.01), have less than a high school education (11.8% vs. 4.1%; P<0.01), and have dental insurance (49.6% vs. 26.8%; P<0.01).

Table 2 describes the distribution of the three health literacy variables for the smaller group of 914 participants. Regarding the measurement of practical skills, 12.6% reported that they felt a moderate degree of uncertainty when filling out forms by themselves. This item was only significantly associated with education level (P<0.01). Regarding word recognition, 21.2% scored in the 0–60 range for the REALM (17). Having poor word recognition was significantly related to older age (P<0.01), race/ethnicity (P<0.01), languages spoken (P<0.01), and education level (P<0.01). For reading comprehension, 6.2% scored in the 0–22 score range for the Short-TOFHLA (19). This health literacy variable was significantly associated with age (P<0.01), race/ethnicity (P<0.01), languages spoken (P<0.01), education level (P<0.01), annual household income (P=0.03), and marital status (P=0.02). As Table 2 shows, there were especially strong dose-response relationships between age and reading comprehension, as well as education level and reading comprehension.

Table 2.

Performance on three health literacy assessments, by selected characteristics (n=914)

| Characteristic | Confidence filling out forms | REALM scores | Short-TOFHLA scores | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low* | High† | 0–44‡ | 45–60 | 61–66 | 0–22¶ | 23–36 | |

| Frequency (row percentage) | |||||||

| Overall | 115 (12.6) | 799 (87.4) | 26 (2.8) | 167 (18.3) | 721 (78.9) | 55 (6.0) | 859 (94.0) |

| Recruitment site | |||||||

| Maryland | 63 (14.1) | 385 (85.9) | 12 (2.7) | 84 (18.7) | 352 (78.6) | 29 (6.5) | 419 (93.5) |

| California | 52 (11.2) | 414 (88.8) | 14 (3.0) | 83 (17.8) | 369 (79.2) | 26 (5.6) | 440 (94.4) |

| Age | |||||||

| 18–24 | 8 (11.1) | 64 (88.9) | 1 (1.4) | 20 (27.8) | 51 (70.8) | 0 (0.0) | 72 (100.0) |

| 25–44 years | 32 (9.9) | 291 (90.1) | 3 (1.0) | 56 (17.3) | 264 (81.7) | 9 (2.8) | 314 (97.2) |

| 45–64 years | 53 (13.3) | 344 (86.7) | 14 (3.5) | 77 (19.4) | 306 (77.1) | 29 (7.3) | 368 (92.7) |

| 65 years or greater | 22 (18.0) | 100 (82.0) | 8 (6.6) | 14 (11.5) | 100 (81.9) | 17 (13.9) | 105 (86.1) |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 52 (11.7) | 391 (88.3) | 13 (2.9) | 87 (19.7) | 343 (77.4) | 34 (7.7) | 409 (92.3) |

| Female | 63 (13.4) | 408 (86.6) | 13 (2.8) | 80 (17.0) | 378 (80.2) | 21 (4.5) | 450 (95.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 37 (10.6) | 312 (89.4) | 8 (2.3) | 41 (11.7) | 300 (86.0) | 9 (2.6) | 340 (97.4) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 49 (14.8) | 283 (85.2) | 12 (3.6) | 73 (22.0) | 247 (74.4) | 26 (7.8) | 306 (92.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1 (2.6) | 38 (97.4) | 1 (2.6) | 9 (23.1) | 29 (74.3) | 1 (2.6) | 38 (97.4) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 10 (14.5) | 59 (85.5) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (15.9) | 58 (84.1) | 5 (7.2) | 64 (92.8) |

| Hispanic | 18 (14.4) | 107 (85.6) | 5 (4.0) | 33 (26.4) | 87 (69.6) | 14 (11.2) | 111 (88.8) |

| Multiple languages spoken now / languages spoken as a child | |||||||

| No / English only | 81 (13.5) | 519 (86.5) | 17 (2.8) | 92 (15.3) | 491 (81.8) | 36 (6.0) | 564 (94.0) |

| Yes / English only | 10 (9.1) | 100 (90.9) | 1 (0.9) | 11 (10.0) | 98 (89.1) | 0 (0.0) | 110 (100.0) |

| Yes / English and other | 10 (11.8) | 75 (88.2) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (18.8) | 69 (81.2) | 3 (3.5) | 82 (96.5) |

| Yes / Other than English | 14 (11.8) | 105 (88.2) | 8 (6.7) | 48 (40.4) | 63 (52.9) | 16 (13.4) | 103 (86.6) |

| Education level | |||||||

| Less than 12 years | 17 (23.3) | 56 (76.7) | 9 (12.3) | 20 (27.4) | 44 (60.3) | 11 (15.1) | 62 (84.9) |

| 12 years of GED | 51 (22.3) | 178 (77.7) | 8 (3.5) | 57 (24.9) | 164 (71.6) | 22 (9.6) | 207 (90.4) |

| Some college | 29 (10.3) | 253 (89.7) | 5 (1.8) | 52 (18.4) | 225 (79.8) | 12 (4.3) | 270 (95.7) |

| College graduate | 18 (5.4) | 312 (94.6) | 4 (1.2) | 38 (11.5) | 288 (87.3) | 10 (3.0) | 320 (97.0) |

| Annual household income | |||||||

| $0–$22,000 | 43 (14.6) | 251 (85.4) | 12 (4.1) | 60 (20.4) | 222 (75.5) | 13 (4.4) | 281 (95.6) |

| $22,001–$44,000 | 33 (12.4) | 234 (87.6) | 8 (3.0) | 46 (17.2) | 213 (79.8) | 21 (7.9) | 246 (92.1) |

| $44,001 or greater | 22 (8.8) | 229 (91.2) | 2 (0.8) | 42 (16.7) | 207 (82.5) | 10 (4.0) | 241 (96.0) |

| Undetermined | 17 (16.7) | 85 (83.3) | 4 (3.9) | 19 (18.6) | 79 (77.5) | 11 (10.8) | 91 (89.2) |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married or co-habitating | 46 (14.1) | 280 (85.9) | 15 (4.6) | 63 (19.3) | 248 (76.1) | 27 (8.3) | 299 (91.7) |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 28 (12.3) | 199 (87.7) | 7 (3.1) | 42 (18.5) | 178 (78.4) | 16 (7.0) | 211 (93.0) |

| Never married | 41 (11.4) | 320 (88.6) | 4 (1.1) | 62 (17.2) | 295 (81.7) | 12 (3.3) | 349 (96.7) |

| Private dental insurance | |||||||

| Yes | 41 (11.7) | 308 (88.3) | 13 (3.7) | 65 (18.6) | 271 (77.7) | 22 (6.3) | 327 (93.7) |

| No | 74 (13.1) | 491 (86.9) | 13 (2.3) | 102 (18.0) | 450 (79.7) | 33 (5.8) | 532 (94.2) |

Note: Statistically significant associations (P<0.05) listed in bold

Low = “Somewhat”, “A little bit”, and “Not at all”

High = “Quite a bit” and “Extremely”

Two lowest categories of REALM scores combined due to small cell size

Two lowest categories of Short-TOFHLA scores combined due to small cell size

Table 3 shows the prevalence of dental visits in the last year and oral health functioning (GOHAI) (23), stratified by the three health literacy measurements. About half of the sample (49.5%) reported having a dental visit either more than a year ago or never. Having a dental visit was not significantly associated with the health literacy variables at either the bivariate level or at the multivariable level (controlling for recruitment site, age, sex, race/ethnicity, languages spoken, education level, annual household income, marital status, and dental insurance status; data not shown). The oral health functioning variable was split into two categories, at the median. Having unfavorable functioning was significantly associated with lower confidence filling out forms (P<0.01) and poor word recognition (P<0.01).

Table 3.

Timing of last dental visit and oral health functioning, by three health literacy assessments (n=914)

| Health literacy measure | Timing of last dental visit | Oral health functioning (GOHAI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| More than one year ago or never | Less than one year ago | Unfavorable | Favorable | |

| Frequency (row percentage) | ||||

| Overall | 452 (49.5) | 462 (50.5) | 453 (49.6) | 461 (50.4) |

| Confidence filling out forms | ||||

| Low* | 66 (57.4) | 49 (42.6) | 81 (70.4) | 34 (29.6) |

| High† | 386 (48.3) | 413 (51.7) | 372 (46.6) | 427 (53.4) |

| REALM scores | ||||

| 0–44‡ | 12 (46.1) | 14 (53.9) | 21 (80.8) | 5 (19.2) |

| 45–60 | 80 (47.9) | 87 (52.1) | 92 (55.1) | 75 (44.9) |

| 61–66 | 360 (49.9) | 361 (50.1) | 340 (47.2) | 381 (52.8) |

| Short-TOFHLA scores | ||||

| 0–22¶ | 27 (49.1) | 28 (50.9) | 32 (58.2) | 23 (41.8) |

| 23–36 | 425 (49.5) | 434 (50.5) | 421 (49.0) | 438 (51.0) |

Note: Statistically significant associations (P<0.05) listed in bold

Low = “Somewhat”, “A little bit”, and “Not at all”

High = “Quite a bit” and “Extremely”

Two lowest categories of REALM scores combined due to small cell size

Two lowest categories of Short-TOFHLA scores combined due to small cell size

Bivariate associations between the three health literacy measures and oral health self-efficacy are listed in Table 4. Slightly less than 1 in 5 (17.9%) study participants reported having low self-efficacy for knowing how to prevent dental caries, and about 1 in 4 (22.9%) reported having low self-efficacy for preventing periodontal disease. Confidence filling out forms and word recognition were significantly associated with dental caries self-efficacy (P=0.01 and P=0.02, respectively) and these two health literacy measures were also significantly associated with periodontal disease self-efficacy (P<0.01 and P<0.01, respectively). By contrast, reading comprehension (Short-TOFHLA) (19) was not significantly associated with either form of self-efficacy.

Table 4.

Level of dental caries and periodontal disease self-efficacy, by three health literacy assessments (n=914)

| Health literacy measures | Dental caries self-efficacy | Periodontal disease self-efficacy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low efficacy | High efficacy | Low efficacy | High efficacy | |

| Frequency (row percentage) | ||||

| Overall | 164 (17.9) | 750 (82.1) | 209 (22.9) | 705 (77.1) |

| Confidence filling out forms | ||||

| Low* | 31 (27.0) | 84 (73.0) | 49 (42.6) | 66 (57.4) |

| High† | 133 (16.6) | 666 (83.4) | 160 (20.0) | 639 (80.0) |

| REALM scores | ||||

| 0–44‡ | 8 (30.8) | 18 (69.2) | 12 (46.1) | 14 (53.9) |

| 45–60 | 39 (23.3) | 128 (76.7) | 50 (29.9) | 117 (70.1) |

| 61–66 | 117 (16.2) | 604 (83.8) | 147 (20.4) | 574 (79.6) |

| Short-TOFHLA scores | ||||

| 0–22¶ | 9 (16.4) | 46 (83.6) | 18 (32.7) | 37 (67.3) |

| 23–36 | 155 (18.0) | 704 (82.0) | 191 (22.2) | 668 (77.8) |

Note: Statistically significant associations (P<0.05) listed in bold

Low = “Somewhat”, “A little bit”, and “Not at all”

High = “Quite a bit” and “Extremely”

Two lowest categories of REALM scores combined due to small cell size

Two lowest categories of Short-TOFHLA scores combined due to small cell size

At the multivariable level (Table 5), confidence filling out forms remained significantly associated with the odds of having unfavorable oral health functioning (P<0.01) and having low periodontal disease self-efficacy (P<0.01) but became not significantly associated with the odds of having low dental caries self-efficacy. Word recognition also remained significantly associated with the odds of having unfavorable oral health functioning (0–44 scores vs. 61–66 scores; P=0.02) and having low periodontal disease self-efficacy (45–60 scores vs. 61–66 scores; P=0.02). Consistent with the bivariate relationships, we found that reading comprehension was not significantly associated with any of the selected outcomes after controlling for confounders.

Table 5.

Crude and adjusted odds of having unfavorable oral health functioning, low dental caries self-efficacy, and low periodontal disease self-efficacy, by three health literacy assessments (n=914)

| Health literacy measures | Oral health functioning (GOHAI) | Dental caries self-efficacy | Periodontal disease self-efficacy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | |

| Confidence filling out forms | ||||||

| Low | 2.69 (1.76–4.12) | 1.98 (1.25–3.15) | 1.83 (1.16–2.87) | 1.58 (0.98–2.54) | 2.91 (1.93–4.38) | 2.48 (1.61–3.80) |

| High (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| REALM | ||||||

| 0–44 | 5.30 (1.78–15.85) | 3.65 (1.11–12.00) | 2.29 (0.97–5.41) | 1.76 (0.71–4.34) | 3.35 (1.51–7.40) | 2.31 (0.99–5.35) |

| 45–60 | 1.31 (0.92–1.86) | 1.07 (0.72–1.59) | 1.56 (1.03–2.36) | 1.41 (0.91–2.17) | 1.68 (1.15–2.45) | 1.54 (1.03–2.30) |

| 61–66 (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Short-TOFHLA scores | ||||||

| 0–22 | 1.43 (0.79–2.57) | 1.03 (0.54–1.97) | 0.96 (0.47–1.98) | 0.70 (0.32–1.53) | 1.75 (0.96–3.10) | 1.31 (0.70–2.47) |

| 23–36 (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Note: Statistically significant associations (P<0.05) listed in bold

Adjusted for recruitment site, age, gender, race/ethnicity, multiple languages spoken now/languages spoken as a child, education level, annual household income, marital status, and private dental insurance status

DISCUSSION

We recruited dental school patients in both California and Maryland in order to capture a broader cross-section of individuals than would have been possible at either site, alone. The differences found between the two recruitment sites revealed that dental school patients are often heterogeneous, presenting various challenges to effective communication and patient care. Depending on geographic location, some dental school clinics are more likely to attract persons who speak multiple languages. When English-speaking providers and clinic staff must communicate with individuals whose first language is not English, the complexities of the interaction are magnified. Even when professional translation services are available, the consistency between the intended message and the translated message is not always guaranteed (29). Again, depending on the setting, some dental school clinics may be more or less likely to attract persons who have dental insurance. Insured patients must balance concerns about the pros and cons of different treatment options against insurance coverage and co-payments. Uninsured patients must balance treatment options against fixed incomes and limited finances. These kinds of competing considerations also place communication demands on providers and staff.

Intuitively, one would have expected that sociodemographic differences that existed between the two recruitment sites would have manifested health literacy differences between the sites. However, it was surprising to note that regardless of how it was measured, the health literacy level of participants in California was nearly identical to that of participants in Maryland. One explanation for this unexpected finding was that sociodemographic factors known to be associated with lower health literacy in one site might have been balanced by factors known to be associated with higher health literacy in the other. For instance, whereas California participants were less likely to speak English as their first language, Maryland participants were less likely to have a college education. At the very least, our findings showed that regardless of which sociodemographic differences might exist across dental school clinics, providers and staff must be ready to contend with patients who have limited health literacy skills. They must also be prepared to tailor their communication strategies to the unique cultural, educational, and language-based demands of the situation. The federal government’s principles of clear communication (30) remain the answer, but our findings imply that a one-size-fits-all approach in dental practice is not likely to be successful.

Regarding the relationship between health literacy and oral health, our analysis showed that health literacy was not consistently associated with the outcome measures, despite our hypothesized expectations. First, no measure of health literacy was associated with dental care utilization (dental visits). This finding was inconsistent with the medical literature, as studies have shown that having limited health literacy skills is strongly related to lower medical visit rates (8, 9). One possible explanation for our unexpected finding was that our study population, adults who presented to a dental school clinic, represented a bias towards care-seeking behaviors. Another reasonable explanation was that some proportion of our study population sought oral health care services from non-dentist providers. Future analyses of MOLHRS data will explore whether alternative sources of healthcare, such as physician’s offices and emergency departments, are influenced by health literacy when dental problems are the primary reason for the visit. Perhaps these other sources of care will be more likely to pick up health literacy-related variability than the more simplistic dental visit indicator, commonly used in oral health investigations.

In contrast to the utilization findings, our analyses showed that health literacy was associated with the other two outcomes, oral health functioning and self-efficacy. However, the relationships between the three health literacy measures and the two outcome measures were inconsistent and, in some cases, became non-significant after controlling for confounding factors. Regarding oral health functioning, those with less confidence filling out forms and those with lower word recognition scores were more likely to score unfavorably on the GOHAI, both at the bivariate level and after controlling for confounders. Reading comprehension, on the other hand, was not significantly associated with oral health functioning. The implication of this inconsistent finding is two-fold. It is possible that each of these three health literacy instruments measured unique attributes and should not be considered interchangeable. It is also conceivable that the three instruments are, indeed, measuring the same concept but some are more sensitive to variability than others. In fact, the possibility of these two explanations is why our conceptual model included several different measures of health literacy within Domain #1. Understanding which of these explanations is more reasonable will occupy future analyses.

Regarding self-efficacy, an additional set of inconsistencies was found. Confidence filling out forms and word recognition were significantly associated with both dental caries self-efficacy and periodontal disease self-efficacy at the bivariate level. However, after controlling for confounders, only the associations with periodontal disease self-efficacy remained significant. Reading comprehension, on the other hand, was not associated with either form of self-efficacy. Taken together, these findings appear to support one of the explanations mentioned earlier. Namely, that these three different instruments measure unique characteristics and should not be thought of as transposable. Why only two of the three health literacy measures were associated with periodontal self-efficacy and none of the measurements were associated with dental caries self-efficacy is still unclear.

In order to determine if language influenced the findings of our analysis, we created an interaction term between the “languages spoken” variable and each of the three health literacy measures. We then entered these interaction terms into the multiple logistic regression models and tested for significance. Across the regression models (data not shown), there were no significant interactions between language, health literacy, and any of the oral health outcomes. These results showed that, in our sample of participants who spoke English, speaking other languages (either during the time of the survey or during childhood) did not act as a mediator for the relationship between health literacy and oral health. Our research team intends to explore the interplay between language, culture, health literacy, and oral health in subsequent analyses. An investigation of individuals who speak only Spanish is currently underway.

The present analysis had a few notable limitations. Testing relationships between health literacy and dental visits, using a sample of individuals presenting for care at a dental clinic, might have caused some biases. Individuals who present for care are different from those who do not for a variety of reasons, including health literacy. In addition, our research team was unable to confirm whether the reporting of past dental utilization was accurate. Future studies should explore the relationship between health literacy and dental utilization among the general population of adults and include multiple confirmatory measures of utilization. Furthermore, given the fact that our findings reflected patients who sought initial care at university-based dental clinics, our results were not generalizable to the general public or to persons who sought dental care in other care settings. Our sample also included relatively few individuals with less than a high school level of education. Those with low levels of education are expected to face the greatest health literacy challenges within the healthcare system and their data would have been most informative. Finally, we did not differentiate participants based on their reason for visiting the dental clinic (e.g., for a dental emergency or for routine care). It is likely that patients who presented for acute care were different from those who might have presented for routine services. These differences will be explored in a subsequent analysis that will test the relationship between health literacy and prospective dental utilization. Through that analysis, our team will be able to determine the extent to which health literacy (and other relevant sociodemographic factors) is associated with dental visit patterns.

These limitations aside, the MOHLRS has provided (and will continue to provide) a valuable opportunity to comprehensively study the relationships between the various dimensions of health literacy and an array of important oral health outcome measures. MOHLRS will also afford opportunities to study the influences of health literacy in the presence of relevant covariates; analyses that will clarify the complex interrelationships between health literacy, education level, language use, access to care, self-efficacy, beliefs and attitudes, and others.

In conclusion, the present analysis provided a flavor of the kinds of relationships that can be studied through the MOHLRS project. It is our expectation that future analyses will allow us to answer questions about the role that different measures of health literacy and various mediating factors play in explaining oral health disparities. In addition, our on-going analyses will provide greater insight into the effects that sociodemographic and healthcare-related covariates have on the relationship between health literacy and oral health. As few previous health literacy studies in medicine or dentistry have focused on the role of confounders, our investigation will provide a wonderful chance to fill some important knowledge gaps.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (R01 DE020858). The authors would like to thank P. Ann Cotten, James Bradley, Laurie-Ann Sayles, Kristi Grimes, Lynette Dozier, Leonard Cohen, Solace Ehioghae, Kathleen Ford, MaryAnn Schneiderman, Sue Tatterson, Folasayo Adunola, Marla Yee, Jie Ge, and Danielle Motley for their valuable contributions.

References

- 1.Ratzan SC, Parker RM. Introduction. In: Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan SC, et al., editors. National Library of Medicine current bibliographies in medicine: Health literacy. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2000. pp. v–viii. NLM Publ. No. CBM 2000-1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman C, Kurtz-Rossi S, McKinney J, Pleasant A, Rootman I, Shohet L. [Accessed on February 10, 2015];The Calgary charter on health literacy: rationale and core principles for the development of health literacy curricula. at http://www.centreforliteracy.qc.ca/sites/default/files/CFL_Calgary_Charter_2011.pdf.

- 3.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C, White S. The health literacy of America’s adults: results from the National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. Demographic characteristics and health literacy; pp. 9–14. NCES 2006-483. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang NJ, Terry A, McHorney CA. Impact of health literacy on medication adherence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(6):741–51. doi: 10.1177/1060028014526562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al Sayah F, Majumdar SR, Williams B, Robertson S, Johnson JA. Health literacy and health outcomes in diabetes: a systematic review. J Gen Int Med. 2013;28(3):444–52. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2241-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fransen MP, von Wagner C, Essink-Bot ML. Diabetes self-management in patients with low health literacy: findings from literature in a health literacy framework. Patient Educ & Counsel. 2012;88(1):44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eichler K, Wieser S, Brugger U. The costs of limited health literacy: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(5):313–24. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0058-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison AK, Myrvik MP, Brousseau DC, Hoffman RG, Stanley RM. The relationship between parent health literacy and pediatric emergency department utilization: a systematic review. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(5):421–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Committee on Health Literacy. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. What is health literacy? In: Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, editors. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. pp. 31–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(Suppl 1):S19–S26. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osborn CY, Paasche-Orlow MK, Bailey SC, Wolf MS. The mechanisms linking health literacy to behavior and health status. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35(1):118–28. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.35.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sørensen K, Van der Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:80–92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JY, Divaris K, Baker AD, Rozier RG, Vann WF., Jr The relationship of oral health literacy and self-efficacy with oral health status and dental neglect. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):923–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Snyder A, Bradley KA, Nugent SM, Baines AD, VanRyn M. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Int Med. 2008;23(5):561–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clayman ML, Pandit AU, Bergeron AR, Cameron KA, Ross E, Wolf MS. Ask, understand, and remember: a brief measure of patient communication self-efficacy within clinical encounters. J Health Comm. 2010;15(Suppl 2):72–79. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.500349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, Murphy PW, Crouch MA. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25(6):391–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atchison KA, Gironda MW, Messadi D, Der-Martirosian C. Screening for oral health literacy in an urban dental clinic. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70(4):269–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, Castro KM, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, Mockbee J, Hale FA. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):514–22. doi: 10.1370/afm.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macek MD, Haynes D, Wells W, Bauer-Leffler S, Cotten PA, Parker RM. Measuring conceptual knowledge in the context of oral health literacy: preliminary results. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70(3):197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons VL, Moriarty C, Jonas K, et al. Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 2006–2015. National Center for Health Statistics. DHHS Publ No. 2014–1365. Vital Health Stat. 2014;2(165):1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atchison KA. The General Oral Health Assessment Index (The Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index) In: Slade GD, editor. Measuring oral health and quality of life. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, Dental Ecology; 1997. pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilbert GH, Duncan RP, Heft MW, Coward RT. Dental health attitudes among dentate black and white adults. Med Care. 1997;35(3):255–71. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lau RR, Hartman KA, Ware JE., Jr Health as a value: methodological and theoretical considerations. Health Psychol. 1986;5(1):25–43. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.5.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rand Corporation. Developing and testing the MOS 20-item short-form health survey: a general population approach. In: Stewart AL, Ware JE Jr, editors. Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books; 1992. pp. 277–90. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallston BS, Wallston KA, Kaplan GD, Maides SA. Development and validation of the health locus of control (HLC) scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1976;44(4):580–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.44.4.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute of Education Sciences National Center for Education Statistics. [Accessed on February 1, 2015];National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) at http://nces.ed.gov/naal/; Raghunathan ATE, Lepkowski JM, van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2001;27(1):85–95. [Google Scholar]; Macek B, MD, Manski RJ, Vargas CM, Moeller JF. Comparing oral health care utilization estimates in the United States across three nationally representative surveys. Health Services Res. 2002;37(2):499–521. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ, Zuckerman B, Abreu M, Medina L, Hardt EJ. Errors in medical interpretation and their potential consequences in pediatric encounters. Pediatr. 2003;111(1):6–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Institutes of Health. Office of Communications and Public Liaison. [Accessed on July 15, 2015];Clear communication. at http://www.nih.gov/clearcommunication/