INTRODUCTION

Bans on flavoured cigarettes have been enacted in the USA,1 the EU2 and elsewhere. However, little is known about industry and consumer counter reactions. Djarum, which controls 97% of flavoured cigarette sales in the USA, immediately released ‘cigars’ resembling their banned counterparts and continued to manufacturer flavoured cigarettes.3 This study describes: (A) online consumer interest4 in, and (B) promotion and availability of Djarum cigarettes, and their cigar replacements, before and after the USA banned flavoured cigarettes in 2009.

METHODS

Google searches originating in the USA including ‘Djarum’ in combination with ‘cigarette/s’ versus ‘Djarum’ in combination with ‘cigar/s’ (eg, ‘Djarum cigarettes’ would be pooled in the cigarette trend) were monitored (google.com/trends), then regressed on time (eg, 2008–2014).

The top 50 Google search results between 29 August 2013 and 28 November 2014 for ‘Djarum cigars’ and ‘Djarum cigarettes’ were classified as websites that described Djarum cigarettes or cigars favourably (promotion), and as websites that sold either product (retailing). Two investigators classified the results (κ=0.88).

RESULTS

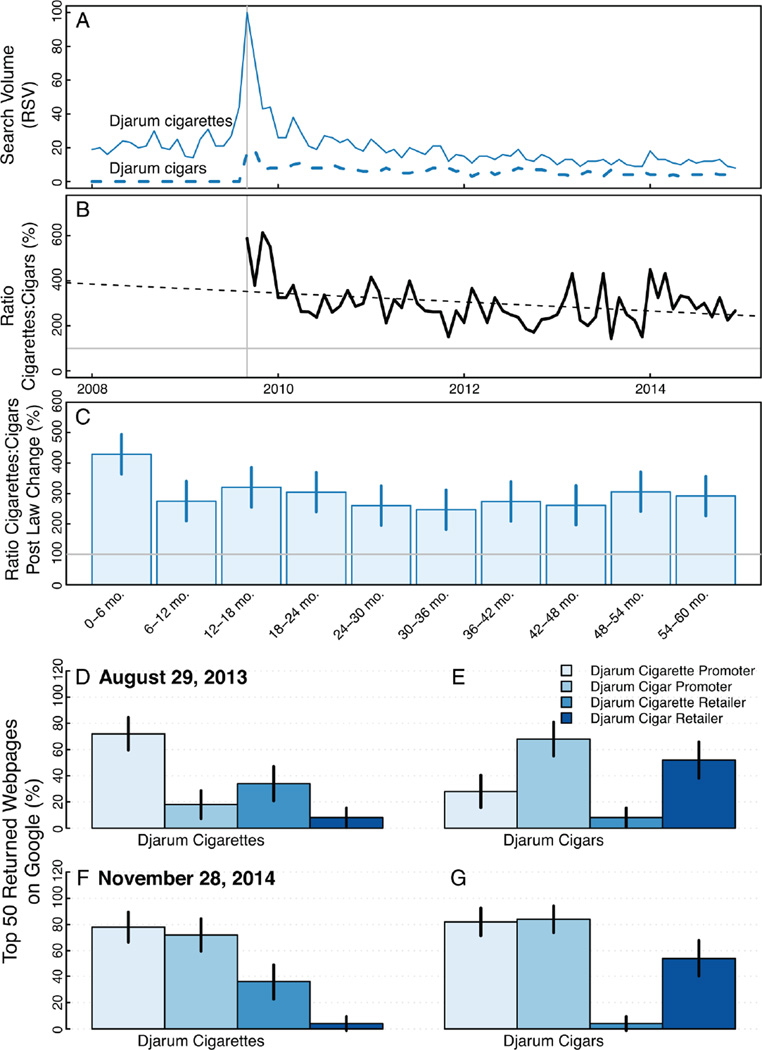

Djarum cigarette searches remained as high as the pre-FSPTCA ban (2008) through 2014, and were far more searched than their replacement cigar line (figure 1). For example, cigarette queries were 428% (95% CI 363 to 494) greater than cigar queries 0–6 months and 291% (95% CI 226 to 356) greater 54–60 months after the FSPTCA, with linear projections suggesting cigarettes will garner more searches through 2015.

Figure 1.

Online Demand and Promotion/Retail For Djarum Cigarettes and Cigars For Google queries in the USA for Djarum cigarettes and cigars around the FSPTCA (A) shows the raw search trends for Djarum cigarette and cigars over the study period, (B) shows the ratio of cigarettes to cigars and (C) shows estimates of the ratio in yearly quarters after FSPTCA. Among the top 50 websites returned for ‘Djarum cigarettes’ and ‘Djarum cigars’ Google queries, (D and E) show the coding for promotion and retail for search results on 29 August 2013 and (F and G) on 28 November 2014. Retailer webpages are reported as a proportion of all webpages, but are a subcategory of promotional webpages. Black lines indicate 95% CIs.

In 2013, among the first 50 search results for ‘Djarum cigarettes’, 72% (95% CI 60 to 84) promoted and 34% (95% CI 21 to 47) sold Djarum cigarettes. Among the results for ‘Djarum cigars’, 28% (95% CI 16 to 40) promoted and 8% (95% CI 1 to 15) sold them. In 2014, 56% (‘Djarum cigarettes’) and 80% (‘Djarum cigars’) of the top 50 websites were new, but 36% (95% CI 23 to 49) of the first 50 search results for ‘Djarum cigarettes’ still sold them.

DISCUSSION

Djarum flavoured cigarettes are still sought and promoted/sold online years after being banned in the USA. Research suggests that the Internet can serve as a vehicle for circumventing tobacco regulation,5 but this study is among the first6 to observe online interest, promotion, and availability of an illicit tobacco product.

Curtailing demand requires persuasive appeals. Google (and others) have banned paid advertising for many cigarette queries, for example, ‘Djarum cigarettes’ search results did not include any ‘pay-per-click’ ads. Regulators can partner with search providers to fill this space with messages discouraging interest in banned products and encouraging cessation, as appropriately worded messages reduce prohibited behaviours as much as by 81%.7

Curtailing supply of an illegal tobacco product requires enhanced enforcement and levying fines on vendors may be necessary.8 Further enforcement is complicated, however, because tobacco vendor websites can be hosted outside the nation where purchases are made.9 By working with search providers, regulators can purge websites that promote or sell banned products from search results, as with copyrighted material such as films.10

Even with the limitations of our study (using a single brand case, search engine, and country), it is evident that flavoured cigarette bans appear to be circumvented online. These online loopholes should be closed.

What this paper adds.

-

▶

Flavoured cigarettes have been banned in the USA since 2009.

-

▶

Bans on flavoured cigarettes are being replicated in other countries, but little is known about consumer and industry counter reactions.

-

▶

Flavoured cigarettes are still widely sought out and available online years after the ban, indicating that improved enforcement or new measures are needed to eliminate demand and availability of flavoured cigarettes.

Acknowledgments

Funding This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute grant number 5R01CA169189-02 and grant number T32CA009492.

Footnotes

Contributors JPA, JWA, BMA, and RW conceived of the study. JPA and JWA drafted the manuscript. JPA, JWA and BMA analysed the data. JPA, JWA, BMA and RW interpreted the data, revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests JWA and BMA share an equity stake in a consultancy, Directing Medicine LLC, that helps other investigators implement some of the ideas embodied in this work. Their organisation serves as technical advisors to the larger funded research project.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement Data used in this study are publicly available from Google Trends (google.com/trends/). Data and coding for websites can be received from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. [accessed 6 Nov 2014];21 USC §301. 2009 :1776–1858. Pub L No. 111-31, 123 Stat http://www.gpo.gov.libproxy.usc.edu/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ31/pdf/PLAW-111publ31.pdf.

- 2. [accessed 25 Apr 2015];Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC. http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/docs/dir_201440_en.pdf.

- 3.Delnevo CD, Hrywna M. Clove cigar sales following the US flavoured cigarette ban. Tob Control. 2015;24(e4):e246–e250. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayers JW, Althouse BM, Ribisl KM, et al. Digital detection for tobacco control: online reactions to the United States’ 2009 cigarette excise tax increase. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:576–583. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen JE, Sarabia V, Ashley MJ. Tobacco commerce on the internet: a threat to comprehensive tobacco control. Tob Control. 2001;10:364–367. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.4.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayers JW, Althouse BM, Dredze M. Could behavioral medicine lead the web data revolution? JAMA. 2014;311:1399–1400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cialdini RB, Demaine LJ, Sagarin BJ, et al. Managing social norms for persuasive impact. Soc Influence. 2006;1:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams RS, Ribisl KM. Internet cigarette vendor compliance with credit card payment and shipping bans. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:243–246. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuel KA, Ribisl KM, Williams RS. Internet cigarette sales and Native American sovereignty: political and public health contexts. J Public Health Policy. 2012;33:173–187. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2012.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. [accessed 16 Jan 2015];Google. Transparency Report. 2015 Jan 16; http://www.google.com/transparencyreport/removals/copyright/