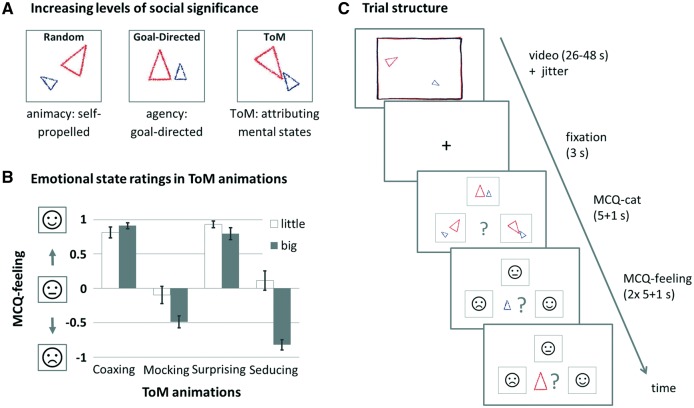

Fig. 1.

Overview over stimuli and experimental design. (A) Stimuli consisted of three types of animated video clips with increasing levels of social significance, represented by three simplified icons during the subsequent categorization (MCQ-cat: ‘Which category did the previously presented animation belong to?’). Example video clips are accessible at https://sites.google.com/site/utafrith/research. (B) ToM animations were additionally rated according to perceived emotionality (MCQ-feeling: ‘How did the little/big triangle feel at the end of the animation?’), which probed for the acquired concept of the displayed emotional states, and thus served as a rough estimation of the subject’s understanding of the cover story: ‘coaxing’ and ‘surprising’ require both triangles to be rated similarly positively, while ‘mocking’ and ‘seducing’ require the little triangle to be rated more positively than the big triangle. Emotional states were represented by schematic faces with an unhappy, neutral and happy expression, respectively. Bar graphs depict average rating scores (± SE) for each ToM animation, with ‘+1’ referring to ‘happy’ and ‘−1’ referring to ‘unhappy.’ Panel (C) depicts the temporal structure of a ToM trial. The presentation of the video clips was preceded by a jitter with variable duration (M = 995.67 ms, s.d. = 418.3). Responses were given with the right thumb, using the left, upper and right key of an MRI compatible button box (Current Designs, PA, USA). As soon as responses were given during MCQ ratings, the chosen icon was framed in red for the duration of one additional second, followed by a blank screen for the remainder of the respective MCQ phase. No feedback on response accuracy was given.