Abstract

Summary

We used data from a large, prospective Canadian cohort to assess the association between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and fracture. We found an increased risk of fractures in individuals who used SSRI or SNRI, even after controlling for multiple risk factors.

Introduction

Previous studies have suggested an association between SSRIs and increasing risk of fragility fractures. However, the majority of these studies were not long-term analyses or were performed using administrative data and, thus, could not fully control for potential confounders. We sought to determine whether the use of SSRIs and SNRIs is associated with increased risk of fragility fracture, in adults aged 50+.

Methods

We used data from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos), a prospective randomly selected population-based community cohort; our analyses focused on subjects aged 50+. Time to event methodology was used to assess the association between SSRI/SNRI use, modeled time-dependently, and fragility fracture.

Results

Among 6,645 subjects, 192 (2.9 %) were using SSRIs or/and SNRIs at baseline. During the 10-year study period, 978 (14.7 %) participants experienced at least one fragility fracture. In our main analysis, SSRI/SNRI use was associated with increased risk of fragility fracture (hazard ratio (HR), 1.88; 95 % confidence intervals (CI), 1.48–2.39). After controlling for multiple risk factors, including Charlson score, previous falls, and bone mineral density hip and lumbar bone density, the adjusted HR for current SSRI/SNRI use remained elevated (HR, 1.68; 95 % CI, 1.32–2.14).

Conclusions

Our results lend additional support to an association between SSRI/SNRI use and fragility fractures. Given the high prevalence of antidepressants use, and the impact of fractures on health, our findings may have a significant clinical impact.

Keywords: Fragility fractures, Osteoporosis, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors

Introduction

Fractures are a major health problem and are associated with a decreased impact on quality of life and a significant economic burden [1]. The majority of fractures in adults aged 50 years or older occur following little or no trauma [2]. Low trauma fractures are the hallmark of osteoporosis, a common condition amongst older adults, affecting 21 % of women and 5 % of men over the age of 50 in Canada [3]. Multiple factors have been implicated as increasing the risk of fragility fractures including antidepressant use [4, 5]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) use may increase the risk of falls, decrease bone mineral density (BMD), and result in subsequent fractures [6]. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis of 34 studies suggested that SSRIs are associated with a clinically significant increase in the risk of fractures of all types [7]. However, the majority of these studies were not long-term analyses, or were performed using administrative data, and, thus, could not fully control for potential confounders or effect modifiers such as lifestyle habits (smoking, alcohol, and physical activity) and use of other drugs and supplements (e.g., calcium/vitamin D). Moreover, the role of depression in the association between antidepressant use and fracture could not be well explored in most studies, which may be important, since depressed patients may differ from others in terms of both lifestyle factors and use of other drugs and supplements [8].

Antidepressants are one of the most commonly prescribed class of drugs worldwide [9]. As such, a carefully designed analysis to help further assess the long-term impact of these drugs and the complex relationships between the use of these drugs, current depression, age, and other factors that might themselves independently alter bone density and/or fracture risk is timely. To address these challenges, we sought to determine whether the use of SSRIs or SNRIs is associated with increased risk of fragility fracture.

Methods

The Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos) is a prospective randomly selected population-based community cohort examining osteoporosis and fracture risk in non-institutionalized adults. Our study included those subjects aged 50 or older. Details of CaMos design and data collection procedures have been reported elsewhere [10]. Briefly, recruitment began in February 1996. Participants completed a comprehensive interviewer-administered questionnaire at baseline, which was repeated 5 and 10 years later. The questionnaire was designed to gather information on medical history and fracture-related risk factors, as well as detailed information on current drug use, including dosage, type of drug, route of delivery, and frequency of use.

Outcomes assessment

Fragility fractures

As part of the CaMos protocol, participants were mailed annual questionnaires to ascertain if they had experienced at least one fracture in the previous year [10]. Participants who reported a fracture in the past year completed then a detailed questionnaire that collected data on the type of fracture and its date. Based on this questionnaire, clinical fragility fractures were defined as any fracture that occurred due to a minimal trauma (e.g., falling from bed, chair, or standing height) and were subsequently confirmed by medical or radiographic reports. Follow-up continued for fracture outcomes until the end of the tenth year of the study.

Drug use assessment and modeling

Participants were asked to report current daily drug use, including SSRIs and SNRIs, at baseline (y0), at year 5 (y5), and year 10 (y10) [10]. Interviewers collected detailed drug information, including dosage and frequency of use. When interviews were conducted in participants’ homes, all contents of their medicine cabinets were reviewed. When interviews were conducted outside of the participants’ homes, they were instructed to bring all of the contents of their medicine cabinets to the interview site. Participants were considered current SSRI users if, at the time of fracture, they were on one or more of citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline, and SNRI users if they were on venlafaxine. We created time-dependent variables in order to account for changes in SSRI/SNRI use, as well as other antidepressants (tricyclic agents (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), serotonin antagonist reuptake inhibitor (SARI), and non-selective monoamine reuptake inhibitors) and other drugs of interest (anxiolytics, antipsychotics, bisphosphonates, antihypertensives, thiazolidinediones, gluco-corticoids, and calcium and vitamin D supplements). These drugs were selected because of their potential associations with falls, fractures, depression, or low BMD [11].

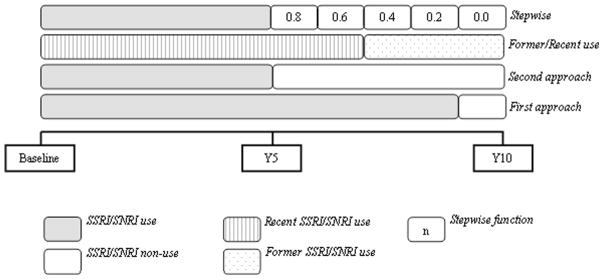

We adopted two alternative assumptions for defining time-dependent drug exposure (Fig. 1). For both approaches, if the participant reported being on use of SSRI/SNRI at two adjacent time points (y0 and y5, or y5 and y10), he/she was considered a current user during the entire 5-year period between these two years. In the first approach, drug use was further assumed to be constant for the period covered by each interview; if, for example, a participant reported being on SSRI/SNRI at y0 but neither at y5 nor y10, then he/she was considered current SSRI/SNRI from year 1 to year 4 and a non-user from year 5 to year 10. Using the second approach, if a participant reported being on SSRI/SNRI therapy at the beginning of the 5-year period but not 5 years later, then he/she was considered a user only in the first year of the period and a non-user in the following 4 years. As part of the second approach, if drug use was reported only at the end of the period but not 5 years earlier, the participant was assumed to be exposed only the last (fifth) year of the corresponding period.

Fig. 1.

Example of time-dependent drug exposure definition. This figure illustrates drug exposure assigned for a participant who reported SSRI/SNRI use at baseline and at year 5 assessments and non-use at year 10. SSRI/SNRI use was classified as “current” from baseline to year 9 with the first approach, and from baseline to year 5 for the second approach. SSRI/SNRI was also coded as “recent” from baseline to year 7 and “former” from year 8 onwards, and, finally, it was approximated as a stepwise function in steps of 0.2, for the last drug exposure definition

In sensitivity analysis, for participants who interrupted drug use during a given 5-year period, time-dependent exposure was defined as a variable [12] whose time-dependent value gradually decreased from initial value of 1 (in the first year of the period) to 0 in the last year, in equal steps of 0.2 reduction for each additional year. For example, a participant who reported use in year 0 but no use in year 5 was assigned values of 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, and 0.2, respectively, for years 1–4.

In additional analyses, we also examined the effect of these drugs on occurrence of fragility fracture by separating recent versus former use and representing them with two different time-dependent covariates. Specifically, if SSRI/SNRI use was confirmed at each of the two adjacent time points, SSRI/SNRI use was coded as “recent”; but if SSRI/SNRI use was discontinued between two adjacent time points, then use was coded as “recent” only during the first half of the corresponding 5-year period and as “former” for the second half. For instance, if a subject reported being on SSRI/SNRI therapy at year 5, but not at year 10, then he/she was considered as a SSRI/SNRI recent user from year 5 to 7 and a former user from year 8 to 10.

In order to evaluate the effect of dose, SSRI/SNRI doses at baseline were standardized using defined daily doses (DDD), defined as the average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults [13]. Based on the prescribed medication dosage, the number of tablets, and the frequency of use of each medication, SSRI/SNRI doses were expressed in DDD units.

Covariates

BMD of the lumbar spine (L1–L4), femoral neck, and total hip were measured using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) with Hologic QDR 1000, 2000, and 4500 or a Lunar DPX densitometer. All BMD results were converted into the Hologic standard using the method described by Genant et al. [14]. Densitometers were calibrated daily, and quality assurance was performed yearly [10].

Falls

Fall history was assessed at baseline and at follow-up assessments (years 5 and 10), by self-report. Specifically, participants were asked whether they had fallen in the last month, at the baseline assessment, or in the past year, at the follow-up questionnaires.

Other covariates assessed at baseline were demographic and socioeconomic variables (age, sex, and employment status), lifestyle characteristics (smoking, alcohol intake, and physical activity), comorbidities, and other clinical variables (diagnosis of depression, depressive symptoms, and presence of radiographic vertebral deformities). Alcohol use was reported as the mean number of drinks per week during the past year. Smoking status at baseline was dichotomized as ever use of daily tobacco for at least 6 months (current smoker) versus non-smoker. Regular exercise was defined as participating in a regular exercise program or activity. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the mental health inventory-5 (MHI-5) [15, 16] and the mental component score (MCS) of the short form 36 questionnaire (SF-36) [17]. The presence of depressive symptomatology was defined as a score <42 on the MCS. In sensitivity analyses, we broadened the definition of depressive symptoms as having <52 on the MHI-5 scale and/or <42 on the MCS. Prevalent radiographic-confirmed vertebral deformities were assessed at baseline using a modified Genant’s semiquantitative method [18]. This method distinguishes fractured or deformed vertebrae (grades 1, 2, and 3) from normal vertebrae (grade 0). Many Genant grade 1 deformities do not represent true fractures [19]; we therefore compared two complementary definitions for vertebral fractures: one using Genant grades 2 or 3 and a second using Genant grades 1 to 3. Comorbidities were assessed using a modified version of the Charlson comorbidity [20] based on the following diagnoses: breast cancer, prostate cancer, uterine cancer, dementia, hypertension, kidney disease, hepatic disease, rheumatoid arthritis, myocardial infarction, stroke and transient ischemic attack, types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. All comorbidities were based on the subjects’ self-report of diagnoses made by their treating physicians.

Statistical analysis

Time to event methodology was used to assess the association between SSRI/SNRI use and time to first fragility fracture. Event time was defined as time from the baseline interview to the first event. Participants who had no fragility fracture during their follow-up were censored at the earliest of loss to follow-up or end of the study (December 31, 2008). Main analyses relied on the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models, with time-dependent covariates representing the history of SSRI/SNRI exposure (see section on “Drug use assessment and modeling”) [21, 22]. The final multivariable Cox model was identified through a combination of a stepwise forward selection of covariates and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) [23] adopted for censored time-to-event data [24]. Specifically, starting from the initial model that included only indicators of SSRI/SNRI exposure, at each step of forward selection we added the most “significant” of the remaining covariates, i.e., the covariate with the lowest p value for its effect adjusted for all covariates included at the earlier steps, and the resulting change in BIC was computed. The selection process ended when BIC no longer decreased, suggesting the best-fitting multivariable model [24]. Based on the corresponding BIC-optimal multivariable Cox model, we reported the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for the relevant measure of SSRI/SNRI exposure. The assumption of proportional hazards (PH) that implies that hazard ratios remain constant over the follow-up time was assessed based on Schoenfeld residuals and tested using the flexible non-PH time-dependent extension of the Cox model [25].

The analysis of the association between baseline SSRI/SNRI dose and the risk of having any fracture during the first 5 years of study was carried out using multivariable logistic regression. An adjusted odds ratio (OR) for one DDD increase in baseline dose, with 95 % confidence intervals, was estimated after adjusting for the same covariates used in our main analysis.

To test the robustness of our main analyses, in sensitivity analyses, we used multiple imputation [26] for five baseline variables: BMD measurements (total hip, lumbar spine, and femoral neck) and depressive symptoms scales (MCS and MHI-5).

Ethics approval was granted through McGill University and the appropriate research ethics board for each participating center. Signed informed consent was obtained from all study participants in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration [10].

Results

Overall, 9,423 participants were enrolled in the original CaMos cohort and the current analyses included 6,645 subjects aged over 50 years, who had the baseline BMD measurement. Among those, 5,556 participants (84 %) underwent repeat assessments at year 5 and 4,011 (60 %) completed the full 10 years of follow-up. Characteristics of SSRI/SNRI users and non-users at study baseline and at year 10 are compared in Table 1. Overall, the distribution of most variables among those who completed the 10-year interview was similar to the entire study population. At baseline, 192 (2.89 %) subjects reported current use of SSRIs or SNRIs; SSRI/SNRI current use increased to 330 (5.94 %) at year 5 and 333 (8.30 %) at year 10. At baseline, compared to non-users, SSRI/SNRI users were more likely to be women, to have more comorbidities, and higher rate of depressive symptoms, but slightly lower prevalence of vertebral deformities (Genant grade ≥1) and use less alcohol. SSRI/SNRI users were also more likely to report previous falls, to have lower BMD at the total hip, and to take psychotropic drugs.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study population

| Characteristic | All participants

|

Those who completed 10-year interview

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRI/SNRI non-users (N = 6,453) | SSRI/SNRI users (N = 192) | SSRI/SNRI non-users (N = 3678) | SSRI/SNRI users (N = 333) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female (%) | 4,580 (71) | 160 (83.3)** | 2,677 (72.8) | 285 (85.6)** |

| Age at enrollment (years ± SD) | 65.71 (8.9) | 65.25 (8.7) | 63.43 (7.9) | 63.65 (8.0) |

| Education level at enrollment | ||||

| High school or higher (%) | 3,896 (60.4) | 125 (65.1) | 2,408 (65.5) | 198 (59.5)** |

| Employment status | ||||

| Full employed (%) | 1,082 (16.8) | 24 (12.5) | 251 (6.8) | 10 (3.0)** |

| Regular activity or program | ||||

| Yes (%) | 3,699 (57.3) | 106 (55.2) | 2,225 (60.5) | 182 (54.7) |

| Number of sedentary hours/day (mean ± SD) | 13.85 (2.9) | 14.11 (3.1) | 13.84 (2.9) | 13.89 (3.2) |

| Current smoker | ||||

| Yes (%) | 930 (14.4) | 39 (20.3) | 458 (12.5) | 53 (15.9) |

| Alcohol intakea—median (IQb) | 0.46 (3) | 0.23 (2)** | 0.46 (4) | 0 (2)** |

| Number of comorbiditiesc | ||||

| 1 or more | 1,583 (24.5) | 70 (36.5)** | 639 (17.4) | 72 (21.6) |

| Depressive symptomsd | ||||

| Yes (%) | 885 (13.8) | 75 (39.7)** | 380 (10.4) | 85 (25.7)** |

| Vertebral deformities (Genant grade 1) | ||||

| Yes (%) | 1,395 (21.6) | 29 (15.1)* | 701 (19.1) | 72 (21.6) |

| Vertebral deformities (Genant grade 2) | ||||

| Yes (%) | 538 (8.3) | 16 (8.3) | 287 (7.8) | 35 (10.1) |

| BMD at enrollment (mean ± SD) | ||||

| Total hip (g/cm2) | 0.88±0.16 | 0.86±0.14* | 0.90±0.15 | 0.86±0.14** |

| Lumbar spine (g/cm2) | 0.95±0.18 | 0.95±0.18 | 0.96±0.18 | 0.94±0.17 |

| Femoral neck (g/cm2) | 0.72±0.13 | 0.70±0.11 | 0.73±0.12 | 0.71±0.12 |

| Falls in previous month before baseline | 398 (6.2) | 31 (16.1) | 220 (6) | 24 (7.2) |

| Drug use | ||||

| Other antidepressants | 251 (3.9) | 19 (9.9)** | 182 (4.9) | 43 (12.9)** |

| Anxiolytics | 294 (4.6) | 28 (14.6)** | 221 (6.0) | 57 (17.1)** |

| Antihypertensives | 1,276 (19.8) | 34 (17.7) | 776 (21.1) | 69 (20.7) |

| Antipsychotics | 28 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 10 (0.3) | 7 (2.1)** |

| Biphosphonates | 112 (1.7) | 4 (2.1) | 853 (23.2) | 94 (28.2)* |

| Corticosteroids (oral + IV) | 89 (1.4) | 2 (1) | 69 (1.9) | 5 (1.5) |

| Intake in previous 12 months median (IQ) | ||||

| Calcium (mg/day) | 902.9 (754.0) | 969.4 (810.9) | 1,234 (959.4) | 1,272 (805.5) |

| Vitamin D (mcg/day) | 6.6 (8.9) | 8.7 (9.4) | 10.2 (17.3) | 10.4 (17.0) |

Variables for which a statistically significant difference exists, based on the chi-square test for categorical and independent groups t test or Wilcoxon test for continuous variables, between SSRI/SNRI users and non-users are indicated

BMD bone mineral density

p<0.05;

p<0.001

Number of alcoholic beverages per week in previous 12 months

IQR (interquartile range): Q3–Q1

Based on modified Charlson index

Depressive symptoms based on score <52 on the MHI-5 scale or <42 on the MCS scale

SSRI/SNRI and fragility fractures

During the 10-year study period, 978 participants experienced at least one fragility fracture, including 161 forearm/wrist fractures and 110 rib fractures. In the time-dependent Cox regression model, current use was associated with an increased risk of fragility fracture (HR, 1.88; 95 % CI, 1.48–2.39). This finding was also present in sensitivity analysis, where SSRI/SNRI use was assumed to continue during the entire 5-year period only if the subject reported being on these drugs both at the beginning and at the end of the period (HR, 1.58; 95 % CI, 1.17–2.14). The final model was adjusted for age, sex, education level, Charlson score, smoking, falls in previous month, BMD hip and lumbar, thiazolidinedione use, vitamin D, and previous deformity (Genant grade ≥2). In these models, the adjusted HR for current SSRI/SNRI use was 1.68 (95 % CI, 1.32–2.14) for the first definition of time-dependent exposure and 1.47 (95 % CI, 1.09–1.99) for the second definition.

Sensitivity analyses

The estimates of association between SSRI/SNRI and fractures remained similar when we changed the definition for deformity (Genant grade ≥1) or depression (combination of both MHI-5 and MCS scales) (data not shown). When we represented previous ever SSRI/SNRI use with separate time-dependent indicators of recent and former use, the unadjusted HR for incident fracture was 1.80 (95 % CI, 1.34–2.42) for recent use and 1.69 (95 % CI, 1.08–2.65) for former use. After adjusting for all the aforementioned covariates, this association remained for recent use (HR, 1.62; 95 % CI, 1.20–2.19), although for former use the confidence interval included the null value (HR, 1.42; 95 % CI, 0.88–2.31) (Table 2). After multiple imputation, the number of participants included in the analysis increased to 7,753. The results were similar to those found with analyses based on complete cases (e.g., HR, 1.46; 95 % CI, 1.08–1.98 for the first definition of time-depended analysis).

Table 2.

Results of univariate and multivariable Cox models using alternative approaches to represent SSRI + SNRI exposure

| Models | Unadjusted HR (95 % CI) | Adjusted HR (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|

| SSRI/SNRI current use—first definitiona | 1.88 (1.48–2.39) | 1.68 (1.32–2.15)b |

| SSRI/SNRI current use—second definitionc | 1.58 (1.17–2.14) | 1.47 (1.09–1.99)d |

| SSRI/SNRI stepwise | 1.83 (1.35–2.47) | 1.69 (1.28–2.22)e |

| SSRI/SNRI recent/former | ||

| Former use | 1.70 (1.08–2.65) | 1.42 (0.87–2.31) |

| Recent use | 1.80 (1.34–2.42) | 1.61 (1.19–2.19)f |

SSRI/SNRI use was assumed to be constant for the period covered by each interview

Adjusted for Charlson score, age, sex, education level, fall in previous month, physical activity, depressive symptoms (MCS scale), BMD hip and lumbar, thiazolidinedione use, vitamin D, and previous vertebral deformity (Genant grade ≥2)

SSRI/SNRI use was assumed to continue during the 5-year period only if the subject reported being on these drugs both at the beginning and at the end of the period

Adjusted for the same variables as above, except smoking

Adjusted for Charlson score, age, sex, education level, fall in previous month, physical activity, depressive symptoms (MCS scale), BMD hip and lumbar, thiazolidinedione and antihypertensive use, vitamin D, and previous vertebral deformity (Genant grade ≥2)

Adjusted for the same variables as above, except education

Dose–effect analysis

This analysis showed that participants taking higher doses of SSRI/SNRI at baseline had a significantly higher risk of fracture (OR for one unit increase in daily defined dose, 1.48; 95 % CI = 1.10–1.94). The effect remained statistically significant after adjusting for confounding covariates (OR = 1.41; 95 % CI = 1.04–1.88).

Discussion

We examined the relationship between use of SSRIs and SNRIs and fragility fracture incidence among 6,645 men and women aged 50 and older in this large prospective Canadian population-based cohort. After adjustment for potential confounding variables, the association remained statistically significant suggesting an independent effect of SSRI/SNRI on risk of fracture which is consistent with previous studies [4, 5, 7]. In our main analysis, the risk of first fracture was increased by more than 50 % in people currently using SSRI or SNRI (HR = 1.68; 95 % CI = 1.32–2.15). Our estimate is very similar to a recent meta-analysis of 12 observational studies, which found that the overall risk of fracture was higher among people using SSRI (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 1.69 and 95 % CI = 1.51–1.90) [27]. Similarly, a Canadian study using the same cohort showed increased fragility fracture risk in SSRI users after 5 years of therapy [4]. Our study extends this observation to a 10-year period, while using time-dependent exposure measures and various sensitivity analyses for the underlying assumptions. Our results also suggest a dose–response relationship between higher SSRI/SNRI doses and increased fracture risk, which is consistent with previously reported findings [5].

Biological mechanisms have been proposed to explain this increased risk of fractures among SSRI and SNRI users. These drugs have an alerting effect, impairing sleep duration and quality and causing insomnia, which may result in daytime drowsiness [28]. This can contribute to increase the risk of fall, a well-known contributor to fracture risk. Risk of a reported fall has been reported to be increased almost 80 % (adjusted OR = 1.79 and 95 % CI = 1.45–2.25) in people currently prescribed an SNRI [6] and SSRI (adjusted OR = 1.8 and 95 % CI = 1.6–2.0) [29].

Several lines of research attest a potential role for the serotonergic system in bone physiology, supporting the hypothesis that SSRIs may have long-term adverse effects on bone health, and therefore increase long-term fracture risk. Functional 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) transporters and receptors are present in osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts, and stimulation of these receptors influences bone cell activities [30, 31]. Consistent with this, use of SSRIs, but not tricyclic antidepressants, was associated with increased rates of bone loss at the hip in older women [32] and men [33]. Some studies suggest that SSRIs may be associated with greater risk of fracture than TCAs, postulating a specific serotonergic effect on bone physiology [34, 35]. Another study found that the risk of osteoporotic fracture was significantly higher for current use of antidepressant with a high affinity for 5-HT transporter (all SSRIs agents) compared to those with a medium or low affinity (like TCAs) [36]. In our study, SSRI/SNRI use was associated with lower BMD at baseline for total hip and lumbar spine, which suggests a possible link between these agents and decreased BMD. Despite this evidence, the physiologic mechanism through which SSRI/SNRI use would negatively affect BMD remains speculative [37]. Level of serum C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX), a marker of bone turnover, was found associated with serotonin levels in premenopausal women [38] while a large population-based study showed an association of depression status with decreased serum 25(OH) D levels and increased serum parathyroid hormone levels in older subjects [39]. Treatment with one SSRI (escitalopram 10 mg/day) was associated with decreased concentrations of parathyroid hormone and CTX, and increased osteocalcin [40].

SSRI/SNRI users tend to have more fracture risk factors than the general population; in fact, our baseline analysis showed that SSRI/SNRI users were more likely to be women, have more comorbidities, and more likely to use other antidepressants and anxiolytics, and to have a history of falls. However, the significant association between current SSRI/SNRI and elevated fracture risk remained even after these variables were controlled for in our analysis.

The major strength of the study is that it was population-based, longitudinal cohort comprising information over a 10-year period, with information on drug exposure and incidence of new fragility fractures. Events of fractures were confirmed by medical or radiographic reports, decreasing the frequency of recall bias or error in patient self-reporting. Furthermore, we were able to control for multiple possible confounding variables which are known to be risk factors for fracture, including falls, bone mineral density, and depression symptoms.

Our study has also some potential limitations. Drug exposure was measured only at three time points, 5 years apart, and we were unable to ascertain if subjects started or stopped the therapy between any two time points. To handle this limitation, we developed several definitions of drug exposure and observed little variation in results across these sensitivity analyses.

Potential confounding by indication should be considered in any observational study of the effects of drugs [8]. Antidepressants are often prescribed for depressive symptoms, and depression itself has been associated with increased risk of fractures [41]. To further address this, we performed analyses controlling for depressive symptoms, using MHI-5 and MCS scales. Previous results on the same cohort showed that depressive symptoms were not independently associated with fragility fractures [42]. This finding, together with our main results, suggests that it may be not only depression but also the antidepressant drugs that induce the excess risk of fractures, at least among SSRI/SNRI users. However, it should be emphasized that depressive symptoms were only measured at discrete time points, i.e., at years 0, 5, and 10 of the follow-up. Although these scales cannot substitute a clinical diagnosis of depression, they are validated measures of affective health which correlate strongly with depression [15, 43, 44]. Even so, it is possible that the observed association between use of antidepressant and risk of fracture still reflects residual confounding by differences in severity of depression or other unmeasured variables.

Our results may lend additional support to an independent association between SSRI/SNRI use and subsequent fragility fracture. Given the high prevalence of antidepressants use, and the impact of fractures on the health, our findings may have a significant clinical impact. Therefore, physicians treating depressive patients should be aware of potential risk of fractures and discuss with their patients both the benefit/risk ration, as well as some preventive measures the patients could adopt (e.g., in terms of optimizing diet, alcohol use, and exercise, for example). Avoiding co-prescription of other agents that can further affect physical balance and contribute to falls (e.g., anxiolytics) should be also recommended. Additionally, where appropriate, the physician should consider BMD screening for high risk subgroups (particularly older females) with appropriate co-management of fracture risk, such as bisphosphonate use if BMD confirms the need.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest Lisa-Ann Fraser has been on the speaker’s bureau for Amgen. Jonathan D. Adachi has been a consultant/speaker for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, and Warner Chilcot, and has conducted clinical trials for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Novartis. David Goltzman has been an advisory board member or consultant for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck Frosst, and Novartis. William Leslie has received speaker fees from Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Novartis and research grants from Amgen and Genzyme.

Contributor Information

C. Moura, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

S. Bernatsky, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

M. Abrahamowicz, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

A. Papaioannou, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

L. Bessette, Université Laval, Québec, Canada

J. Adachi, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

D. Goltzman, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

J. Prior, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

N. Kreiger, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

T. Towheed, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada

W. D. Leslie, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada

S. Kaiser, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada

G. Ioannidis, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

L. Pickard, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

L.-A. Fraser, Western University, London, Canada

E. Rahme, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

References

- 1.Adachi JD, Ioannidis G, Pickard L, Berger C, Prior JC, Joseph L, Hanley DA, Olszynski WP, Murray TM, Anastassiades T, Hopman W, Brown JP, Kirkland S, Joyce C, Papaioannou A, Poliquin S, Tenenhouse A, Papadimitropoulos EA. The association between osteoporotic fractures and health-related quality of life as measured by the Health Utilities Index in the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos) Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(11):895–904. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, Atkinson S, Brown JP, Feldman S, Hanley DA, Hodsman A, Jamal SA, Kaiser SM, Kvern B, Siminoski K, Leslie WD. 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. Cmaj. 2010;182(17):1864–1873. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger C, Goltzman D, Langsetmo L, Joseph L, Jackson S, Kreiger N, Tenenhouse A, Davison KS, Josse RG, Prior JC, Hanley DA. Peak bone mass from longitudinal data: implications for the prevalence, pathophysiology, and diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(9):1948–1957. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards JB, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Joseph L, Whitson HE, Prior JC, Goltzman D. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on the risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(2):188–194. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vestergaard P, Prieto-Alhambra D, Javaid MK, Cooper C. Fractures in users of antidepressants and anxiolytics and sedatives: effects of age and dose. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(2):671–680. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2043-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gribbin J, Hubbard R, Gladman J, Smith C, Lewis S. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and the risk of falls in older people: case–control and case-series analysis of a large UK primary care database. Drugs Aging. 2011;28(11):895–902. doi: 10.2165/11592860-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabenda V, Nicolet D, Beaudart C, Bruyere O, Reginster JY. Relationship between use of antidepressants and risk of fractures: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):121–137. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker AM. Confounding by indication. Epidemiology. 1996;7(4):335–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen DG, Rosholm JU, Gichangi A, Vach W. Increased use of antidepressants at the end of life: population-based study among people aged 65 years and above. Age Ageing. 2007;36(4):449–454. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreiger N, Tenenhouse A, Joseph L, Mackenzie T, Poliquin S, Brown JP, Prior JC, Rittmaster RS. The Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos): background, rationale, methods. Can J Aging. 1999;18(3):376–387. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Anxiolytics, sedatives, antidepressants, neuroleptics and the risk of fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(6):807–816. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0065-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraser LA, Leslie WD, Targownik LE, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD. The effect of proton pump inhibitors on fracture risk: report from the Canadian Multicenter Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(4):1161–1168. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2112-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2013. Vol. 16. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology; Oslo: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Genant HK, Grampp S, Gluer CC, Faulkner KG, Jergas M, Engelke K, Hagiwara S, Van Kuijk C. Universal standardization for dual X-ray absorptiometry: patient and phantom cross-calibration results. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9(10):1503–1514. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650091002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA, Ware JE, Jr, Barsky AJ, Weinstein MC. Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Med Care. 1991;29(2):169–176. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers WH, Adler DA, Bungay KM, Wilson IB. Depression screening instruments made good severity measures in a cross-sectional analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(4):370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JEJ, Snow K, Kowinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: manual and Interpretation Guide. 1. The Health Institute; Boston: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8(9):1137–1148. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenchik L, Rogers LF, Delmas PD, Genant HK. Diagnosis of osteoporotic vertebral fractures: importance of recognition and description by radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(4):949–958. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.4.1830949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abrahamowicz M, Beauchamp ME, Sylvestre MP. Comparison of alternative models for linking drug exposure with adverse effects. Stat Med. 2012;31(11–12):1014–1030. doi: 10.1002/sim.4343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abrahamowicz M, Tamblyn R. Drug utilization patterns. In: Armitage P, Colton T, editors. Encyclopedia of biostatistics. 2. Vol. 4. Wiley; Chichester: 2005. pp. 1533–1553. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6(2):461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volinsky CT, Raftery AE. Bayesian information criterion for censored survival models. Biometrics. 2000;56(1):256–262. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abrahamowicz M, MacKenzie TA. Joint estimation of time-dependent and non-linear effects of continuous covariates on survival. Stat Med. 2007;26(2):392–408. doi: 10.1002/sim.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-care databases: an overview and some applications. Stat Med. 1991;10(4):585–598. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eom CS, Lee HK, Ye S, Park SM, Cho KH. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(5):1186–1195. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darowski A, Chambers SA, Chambers DJ. Antidepressants and falls in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(5):381–394. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200926050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thapa PB, Gideon P, Cost TW, Milam AB, Ray WA. Antidepressants and the risk of falls among nursing home residents. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(13):875–882. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809243391303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Battaglino R, Fu J, Spate U, Ersoy U, Joe M, Sedaghat L, Stashenko P. Serotonin regulates osteoclast differentiation through its transporter. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(9):1420–1431. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bliziotes M, Eshleman A, Burt-Pichat B, Zhang XW, Hashimoto J, Wiren K, Chenu C. Serotonin transporter and receptor expression in osteocytic MLO-Y4 cells. Bone. 2006;39(6):1313–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diem SJ, Blackwell TL, Stone KL, Yaffe K, Haney EM, Bliziotes MM, Ensrud KE. Use of antidepressants and rates of hip bone loss in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1240–1245. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haney EM, Chan BK, Diem SJ, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Barrett-Connor E, Orwoll E, Bliziotes MM. Association of low bone mineral density with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use by older men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1246–1251. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coupland C, Dhiman P, Morriss R, Arthur A, Barton G, Hippisley-Cox J. Antidepressant use and risk of adverse outcomes in older people: population based cohort study. Bmj. 2011;343:d4551. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gagne JJ, Patrick AR, Mogun H, Solomon DH. Antidepressants and fracture risk in older adults: a comparative safety analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(6):880–887. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verdel BM, Souverein PC, Egberts TC, van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, de Vries F. Use of antidepressant drugs and risk of osteoporotic and non-osteoporotic fractures. Bone. 2010;47(3):604–609. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bliziotes M. Update in serotonin and bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(9):4124–4132. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Modder UI, Achenbach SJ, Amin S, Riggs BL, Melton LJ, 3rd, Khosla S. Relation of serum serotonin levels to bone density and structural parameters in women. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(2):415–422. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuchuk NO, Pluijm SM, van Schoor NM, Looman CW, Smit JH, Lips P. Relationships of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D to bone mineral density and serum parathyroid hormone and markers of bone turnover in older persons. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(4):1244–1250. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aydin H, Mutlu N, Akbas NB. Treatment of a major depression episode suppresses markers of bone turnover in premenopausal women. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(10):1316–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mussolino ME. Depression and hip fracture risk: the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(1):71–75. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitson HE, Sanders L, Pieper CF, Gold DT, Papaioannou A, Richards JB, Adachi JD, Lyles KW. Depressive symptomatology and fracture risk in community-dwelling older men and women. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2008;20(6):585–592. doi: 10.1007/bf03324888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beusterien KM, Steinwald B, Ware JE., Jr Usefulness of the SF-36 Health Survey in measuring health outcomes in the depressed elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1996;9(1):13–21. doi: 10.1177/089198879600900103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wells KB, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Greenfield S, Ware JE., Jr Detection of depressive disorder for patients receiving prepaid or fee-for-service care. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262(23):3298–3302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]