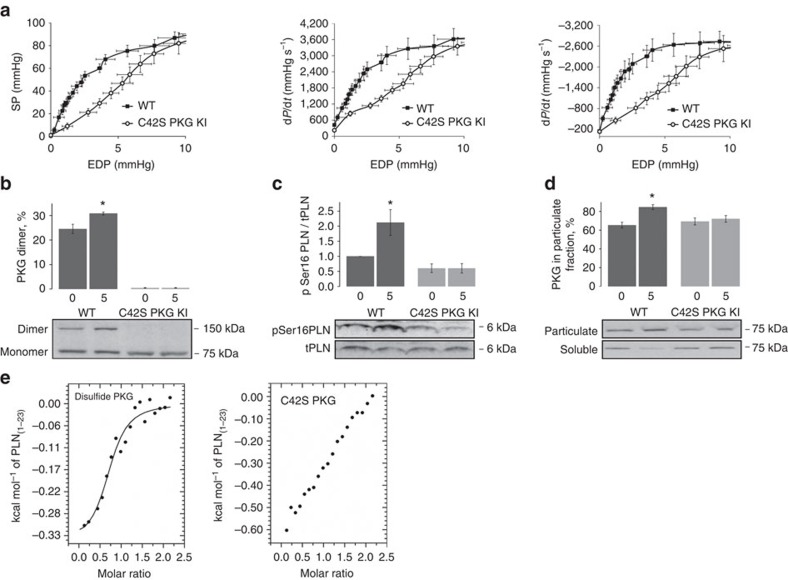

Figure 2. Isolated hearts from C42S PKGIα KI mice have impaired Frank–Starling responses.

(a) Curves showing the variation in SP, rate of contraction (+dp/dt), and rate of relaxation (−dp/dt) as a function of EDP for Langendorff-perfused WT and KI hearts. Cardiac performance increased with EDP, that is, stretch, according to the Frank–Starling law. However, the responses were significantly reduced in the KI hearts compared with WT (P<0.05; n=8). (b) Immunoblotting showed that oxidation of PKGIα to the disulfide dimer increased with increasing stretch (from 0 mm Hg to 5 mm Hg EDP) in the WT hearts but not in the KI (*P<0.05; n=5). (c) Phosphorylation of PLN Ser16 was also significantly increased in the WT but not KI hearts with increased diastolic stretch (*P<0.05; n=5). (d) Subcellular fractionation of WT and KI hearts perfused at different EDPs followed by immunoblotting revealed a significant increase in the amount of PKGIα in the particulate fraction from stretched WT myocardium compared with the particulate fraction from unstretched WT myocardium (*P<0.05; n=5). No stretch-dependent changes in PKGIα abundance were observed in fractions from the KI tissue. Error bars show s.e.m. and P values were determined by t-test. (e) ITC analysis of the interaction between the cytoplasmic domain of PLN (residues 1–23) with disulfide-activated PKGIα and the C42S mutant. A sigmoidal binding isotherm can be fitted to the titration data for oxidized PKGIα which is consistent with one PKGIα disulfide dimer binding to one PLN peptide with a Kd of ∼7 μM. Although the ITC data for C42S PKGIα also suggests a direct interaction with the cytoplasmic domain of PLN, this is markedly weaker than for oxidized PKGIα as the integrated data cannot be fitted to a sigmoid-shaped binding curve under the same experimental conditions.