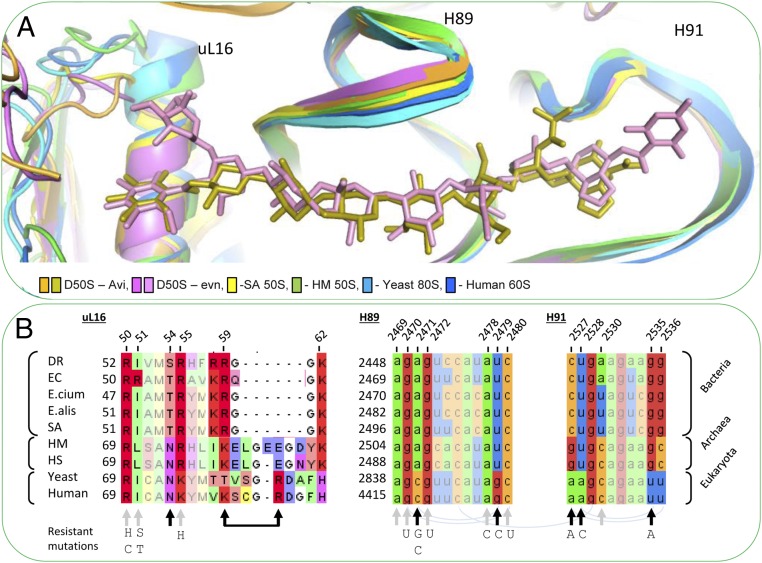

Fig. 7.

Orthosomycins’ selectivity. (A) Comparison among the conformations of H89, H91, and uL16 in 60S of H. sapiens (PDB ID code 3J3F; blue), 80S from the yeast S. cerevisiae (PDB ID code 3U5D; light blue), D50S–avi (orange-gold), D50S–evn (purple-pink), S. aureus 50S (PDB ID code 4WCE; yellow), and the archaeon H. marismortui 50S (PDB ID code 4HUB; green). The overall structure of H89 and H91 is conserved among bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes. The rProtein uL16 in archaea and eukaryotes possesses a longer α1 helix. (B) Sequence alignment of uL16 (Left) of D. radiodurans R1 (DR), E. coli K12 (EC), E. faecium V582 (E.cium), E. faecalis 29212 (E.alis), S. aurous NCTC 8325 (SA), H. marismortui (Hmar), H. salinarum R1 (Hsal), S. cerevisiae 204508 (yeast), and H. sapiens 9606 (human), and 23S rRNA alignment of H89 (Middle) and H91 (Right) of the same organisms. Within the sequence alignments, paired bases (arch), avi and evn binding site (gray arrows), and variance in binding site (black arrows). Resistance-causing mutations are listed below sequence alignment.