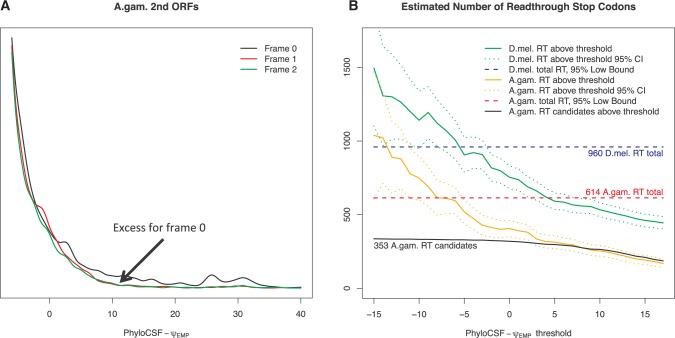

Fig. 4.

Estimating the number of readthrough stop codons. (A) Distribution of PhyloCSF-ΨEmp scores of all regions starting 0, 1, and 2 bases after an annotated A. gambiae stop codon (black, red, green, respectively) and continuing until the next stop codon in that frame, excluding ones that overlap an annotated coding region in any frame or whose alignment has inadequate branch length. Since readthrough second ORFs would have elevated score only in frame 0, whereas regions with high score due to other causes would be distributed among all three frames, the excess of high scoring regions in frame 0 allows us to estimate the number of readthrough stop codons, including ones that we cannot distinguish individually. (B) Graph showing, for each PhyloCSF-ΨEmp score threshold, t, the estimated number of readthrough regions having a score higher than t, in A. gambiae (orange) and D. melanogaster (green), with 95% confidence intervals (dotted curves), and the number of A. gambiae readthrough candidates whose readthrough regions have score higher than t (black curve). Also, 95% confidence lower bound for the total number of functional readthrough stop codons in A. gambiae (red dashed line) and D. melanogaster (blue dashed line). The estimated number of readthrough regions having a score greater than 0 is 406 in A. gambiae and 754 in D. melanogaster, and the difference is unlikely to be due to differential annotation quality. The total numbers of functional readthrough regions of all scores are, with 95% confidence, at least 614 in A. gambiae and 960 in D. melanogaster, which are much larger than the numbers of candidates reported individually. In A. gambiae, the number of readthrough candidates is close to the estimated number of readthrough stop codons for PhyloCSF-ΨEmp > 5.0, indicating that our candidate list includes almost all high-scoring readthrough regions.