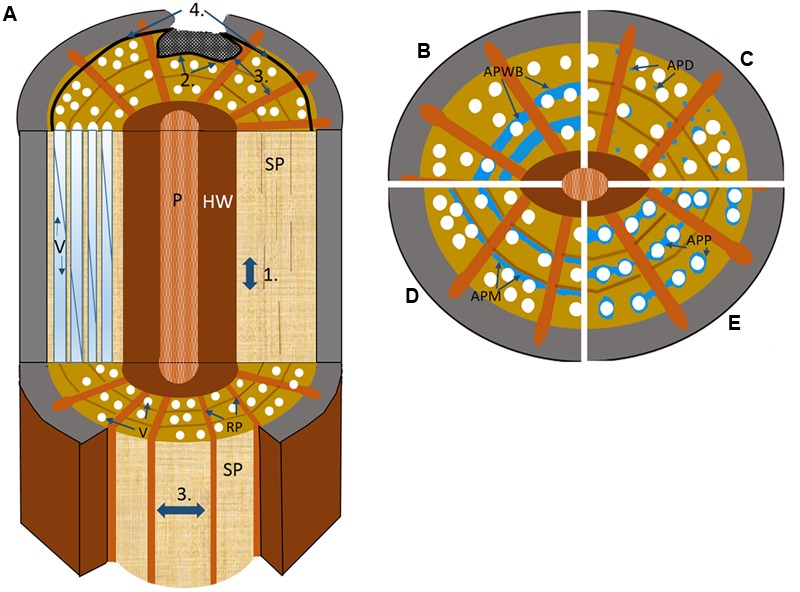

FIGURE 2.

Schematic drawing illustrating the four walls of the CODIT model. (A) Wall 1: limits the up or downward movement of decay through the plugging of the vascular elements by RAP via tyloses or gels; Wall 2: limits the radial movement of decay (both inward and outward) at the growth ring boundary, where in addition to strongly lignified fibers, apotracheal marginal AP contributes, and possibly the wide bands of AP in many tropical species in the absence of growth rings; Wall 3: the strongest wall at the time of wounding, which limits the lateral movement of decay spread through chemical alteration of ray parenchyma (RP) along with the plugging of vessels via the contact RP cells; Wall 4: the strongest wall and the only wall formed after wounding, forms a chemically distinct and impervious barrier that separates new wood from the old infected wood to its interior. P, pith; SP, sapwood; RP, ray parenchyma; V, vessel. (B–E) the possible contributions different AP patterns make to defense based on cross-sectional wood representations divided into quarters, with (B) axial parenchyma wide banded (APWB) often present in the absence of distinct growth rings in tropical species, where it likely functions as part of wall 2, (C) axial parenchyma diffuse (APD) found predominately in temperate species where AP is often seen to be scattered more randomly and in low amounts, which could indicate that these species are poor at forming reaction zones (wall 1–2) with RP (wall 3) possibly taking on a greater defensive role, (D) axial parenchyma marginal (APM) forms an important defensive component alongside the highly lignified fibers at the growth ring boundary, and (E) axial parenchyma paratracheal (APP), more often present in large-vesselled species of tropical origin.