Abstract

Esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB), also known as olfactory neuroblastoma, is a rare malignant tumor that accounts for 3% of all tumors of the nasal cavity. The incidence of ENB is 0.4 cases per million in the general population, and the most common symptoms are nasal obstruction and epistaxis. Previous studies have indicated the presence of somatostatin receptors in this tumor type. Common treatment strategies for ENB include resection and adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy (combined treatment); however, the rate of recurrence is high. Treatment of neuroendocrine tumors using radionuclides bound to somatostatin analogues is well established in clinical practice. However, a standard and effective therapeutic approach has not been reported for ENB. The current study described the case of a 74-year-old female with numerous recurrences of ENB following multiple treatments and without possibility of resection. The patient was treated with the radiolabeled-somatostatin analogue, 177Lutetium-DOTA-octreotate (177Lu-DOTA-TATE), which successfully controlled the disease. This suggests that 177Lu-DOTA-TATE is a potential treatment for ENB and may represent an effective alternative and novel therapeutic strategy for this disease.

Keywords: esthesioneuroblastoma, lutetium 177, neuroendocrine tumors, olfactory neuroblastoma, nuclear medicine, radioisotopes

Introduction

Esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB), or olfactory neuroblastoma, was first described by Berger et al in 1924 (1). ENB is a rare malignant tumor accounting for 3% of all intranasal tumors (2), with an estimated incidence of 0.4 cases per million in the general population (3,4). The tumor may occur at any age, however, it has a bimodal distribution with incidence peaks in the 2nd and 6th decades of life. In addition, there appears to be no gender bias in the incidence of ENB (4,5). Whilst the histological origin of this tumor is not fully known, it has been proposed that ENB originates from stem cells of the olfactory epithelium-derived neural crest (6,7). The most common symptoms are nasal obstruction, epistaxis and persistent nasal discharge. Less commonly, ENB may manifest as visual alterations, headache, orbital proptosis, diplopia, hyposmia, anosmia, pain and facial sweating (4,7). This tumor appears as a polyploid mass surrounding the upper aspect of the nasal cavity, with frequent involvement of the cribriform plate region. Tumor expansion predominantly occurs at the paranasal sinuses, orbits and skull base, while the tumor growth ranges from indolent to rapid in certain cases (3). Metastasis to the cervical lymph nodes occurs in 10–44% of ENB cases (8,9). However, to the best of our knowledge, only 4 cases of retropharyngeal lymph node metastases have been reported in the literature to date (10).

For the diagnosis, staging and follow-up of ENBs, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used, which commonly detect the presence of a heterogeneous mass in the upper nasal cavity, cribriform plate and anterior cranial fossa (11). Staging of ENB tumors follows the criteria described by Kadish et al (12) in 1976. Patients presenting with the tumor restricted to the nasal cavity are classified into stage A, patients with cancer involving the nasal cavity and at least one sinus are classified into stage B, and stage C refers to malignancy with extension beyond the paranasal cavities (12).

An effective standard treatment for ENB has yet to be established. A meta-analysis performed by Dulguerov et al (7) indicated that optimal treatment is complete surgical resection followed by radiation therapy, which showed lower recurrence rates and 65% survival at five years. Multimodality therapy, including chemotherapy, has been suggested by a number of studies (13–16). In addition, recent study by Uslu et al (17) reported the case of a 69-year-old patient with olfactory neuroblastoma who was treated by combined surgical excision and radiotherapy. Currently, treatment with radionuclides bound to somatostatin analogues is performed in selected patients with neuroendocrine tumors, with considerable response. In order to confirm the presence of somatostatin receptors in the tumor, a whole body scan (WBS) with indium-111 (111In)-octreotide is commonly performed. Lutetium-177 (177Lu) is a radionuclide that emits β particles and γ photons, and can be used in the treatment of certain neoplasms when attached to a somatostatin analogue, such as DOTA-octreotate (known as 177Lu-DOTA-TATE). Patients with somatostatin-positive neuroendocrine tumors may be administered three to four doses of 177Lu-DOTA-TATE intravenously, accumulating a total dose of 22,200–29,600 GBq (18,19). Co-treatment with amino acids (such as 2.5% arginine and 2.5% lysine) is recommended for renal protection, and is administered prior to and following each therapeutic dose (20). However, adjuvant treatment with somatostatin analogues has not been previously investigated in patients with ENB, due to the rarity of the disease.

The present study described the case of a 74-year-old female with numerous recurrences of ENB following multiple treatments and without possibility of resection, who was successfully treated with 177Lu-DOTA-TATE. The present study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Barretos Cancer Hospital (São Paulo, Brazil).

Case report

A 74-year-old female experienced an episode of epistaxis in June 1993. At the time, an MRI scan of the sinuses revealed an expansive lesion involving the nasal cavity and sphenoid sinus, ethmoid cells and infiltration of the dura mater and cribriform lamina. The patient underwent surgical resection of the tumor at Catanduya's Hospital (São Paulo, Brazil) and pathological tests indicated a diagnosis of ENB. Subsequently, the patient underwent radiotherapy with 6,760 cGy (between July and August, 1993) and chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, cisplatin and etoposide (July, 1993).

In 2003, the patient noticed a right cervical node, and following excision, a nodular lymph node metastasis of the primary tumor was confirmed by immunohistochemistry. Subsequently, in 2005, another cervical node was identified. This was removed by biopsy and immunohistochemical tests confirmed further ENB metastasis.

In 2008, the patient was referred to the Barretos Cancer Hospital (Barretos, Brazil) because of neck and malar nodules causing local deformity, and was admitted to the Department of Head and Neck Surgery (February, 2008). The patient exhibited growth of the cervical nodes, however, did not present with other complaints. Clinical physical examination revealed a 6.0 cm nodule in the right cervical region, with a solid and not very mobile lymph node located in the left submandibular region, while 4.0 and 2.0 cm nodules with the same features were also observed in the left cervical aspect. The patient subsequently underwent right neck dissection at levels I, II, III and IV (April, 2008), from which pathological tests, including immunohistochemistry, indicated poorly-differentiated neoplasms in 10/13 of the removed lymph nodes and multiple foci of venous invasion. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed the presence of metastatic ENB; results showed positivity for 34B, 35B, cromogramine and S11, and negativity for AE1/AE3, p63, synaptofisine and enolasis. Subsequent radical surgery of the left neck lymph nodes (June, 2008) revealed conglomerate lymph node metastases in 7/13 of the removed nodes, with soft tissue invasion to the adjacent dermis. In March 2009, an oropharynx CT scan indicated metastatic masses with unclear limits. One of the masses was located in the left malar region measuring 2.7×1.5×2.5 cm, superficial to the maxillary sinus and covering the intra-orbital foramen, and another was located in the left retropharyngeal region, measuring 1.8×1.5×2.1 cm and surrounding the internal carotid artery. Resection was not an option at this point, and the patient was treated with radiotherapy.

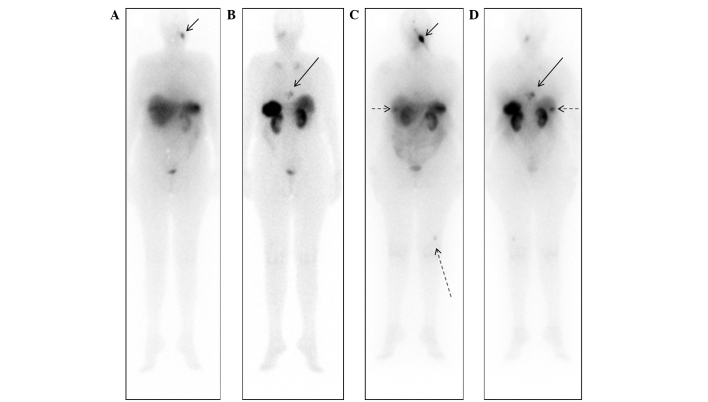

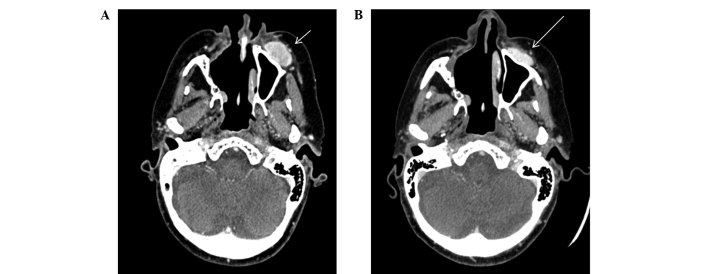

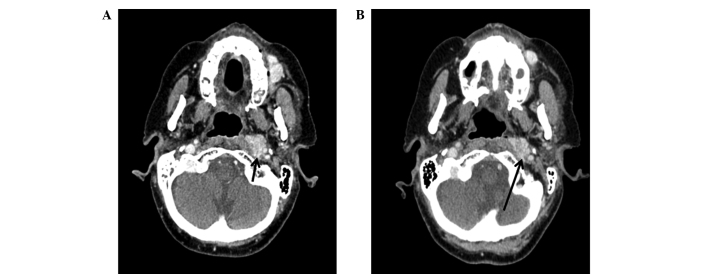

In July 2009, the patient reported a left malar node and upon clinical examination, the mass was observed to be solid, deep and difficult to measure. A WBS using iodine-131-metaiodobenzylguanidine (Nuclear and Energetic Research Institute, São Paulo, Brazil) identified no abnormal uptake; however, a diagnostic WBS with 111In-octreotide (Nuclear and Energetic Research Institute) showed uptake in the left malar and posterior thoracic regions (Fig. 1A and B), indicating the potential for treatment with somatostatin analogue therapy using 177Lu-DOTA-TATE (Nuclear and Energetic Research Institute). A thoracic CT scan at this time indicated mild sclerosis of the T9 vertebra. The first treatment with 7,400 MBq of 177Lu-DOTA-TATE was administered in January 2010. A WBS at 24 h post-treatment with 111In-Octreotide revealed uptake in the left malar region, lower thoracic segment, segments VI/VII of the liver and in the distal femur (Fig. 1C and D). The second round of 7,400 MBq of 177Lu-DOTA-TATE therapy was administered in April 2010, with good uptake of the radiopharmaceutical and without marked alterations in the imaging pattern. A CT scan performed at this time revealed a hyperdense nodule in the right lobe of the liver and increased sclerosis in the T9 vertebra. The third round of 7,400 MBq of 177Lu-DOTA-TATE therapy was administered in June 2010, and a WBS post-treatment with 111In-Octreotide revealed a marked reduction in the size of the lesions. However, CT scans indicated minimal reduction of the left malar nodule (Fig. 2) and the persistence of the retropharyngeal node (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

111In-octreoscan whole body scans prior to somatostatin analogue therapy. (A) Anterior projection, showing uptake in the left malar aspect (small arrow) pre-treatment (July, 2009); (B) posterior projection, showing uptake in the thoracic regions (large arrow) pre-treatment (July, 2009). (C) Anterior and (D) posterior projections of whole body scans at 24 h following the first round of 177Lu-DOTA-TATE therapy (January, 2010). Abnormal uptake was observed in the left malar region (short continuous arrow), lower thoracic segment (large continuous arrow), liver (short dashed arrow) and in the left distal femur (large dashed arrow). 111In, indium-111; 177Lu, lutetium-177.

Figure 2.

Facial computed tomography, axial view. (A) Prior to 177Lu-DOTA-TATE therapy (July, 2009). Well limited ovoid nodule, localized in the left anterior malar subcutaneous plain, with moderate and heterogeneous post-contrast enhancement, measured 30 mm (short arrow). (B) Following the third round of 177Lu-DOTA-TATE therapy (June, 2010), showing a 5 mm reduction in the malar nodule (large arrow). 177Lu, lutetium-177.

Figure 3.

Facial computed tomography, axial view. (A) Prior to177Lu-DOTA-TATE therapy (July, 2009). Nodule localized in the left retropharyngeal space, with imprecise limits, moderate post-contrast enhancement and direct contact with the carotid artery, measuring 21 mm (small arrow). (B) Following the third round of 177Lu-DOTA-TATE therapy (June, 2010), showing a minimal (1 mm) reduction in the nodule size (large arrow). 177Lu, lutetium-177.

A follow-up WBS with 111In-Octreotide in March 2011 demonstrated near complete resolution of the thoracic lesion and a marked reduction of the lesion in the liver and the region corresponding to the malar lesion. In addition, a CT scan in January 2012 confirmed the radiological stability of the disease following the three treatments with 177Lu-DOTA-TATE.

Discussion

ENB is a rare neuroectodermal neoplasm arising from the olfactory neuroepithelium. A study performed in Denmark, reviewing patients with ENB between 1978 and 2000, gave an incidence of 0.4 patients/million inhabitants per year (40 cases) (3). Staging such rare tumors can be challenging, since small series of subjects are analyzed. Morita et al (21) proposed a modification of the Kadish system, redefining stage C and adding stage D, for patients with distant metastasis. By means of that classification, the patient in the present study fits in stage C with disease spreading beyond the paranasal sinuses. The rationale for the treatment in the present study was the fact that somatostatin receptors are expressed at high levels in ENB (22) and thus it would be susceptible to somatostatin analogues, such as DOTA-DATE-177Lu.

In a previous study, immunohistochemical analysis was performed on ENB samples in order to investigate the presence of somatostatin receptor subtypes (20). The study demonstrated that type 2 somatostatin receptors have a high affinity for octreotide (20). In the MAURITIUS Phase II clinical trial, the use of 90Y-DOTA, which has an affinity for type 2, 3, 4 and 5 somatostatin receptors, led to the regression or stabilization of disease in 60% of patients with varying types of progressive neuroendocrine cancer (23). However, an agent specific for the type 2 somatostatin receptor has yet to be reported (22). The occurrence of metastasis to the retropharyngeal lymph nodes reported in the current case study is considered rare. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first report of the use of somatostatin analogues in the treatment of ENB. Treatments performed since 1993 follows literature recommendations of Dulguerov's meta-analysis (7), including surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Adjuvant chemotherapy was performed with cisplatin and etopside, but without the subsequent proton radiaton used by Harvard University in a series of 9 patients, with good results (24).

Although described as rare, retropharyngeal lymph node metastasis was considered as frequent in a study by Howella et al (25). Despite the absence of a central nervous system invasion, the patient in the present study showed a vertebrae lesion with somatostatin analogue uptake, highly suggestive of secondary involvement. In addition, hepatic metastasis has been reported (26).

To the best of our knowledge, at the treatment period time, no other patient with ENB was treated with somatostatin receptor analogue linked to Lutetium 177. However, in April 2015 a case report was published with the initiative. The subject was submitted to four cycles of octreotide-111In and three cycles of DOTA-TATE-177Lu, alleviating the symptoms and improving quality of life. However, the disease progressed and the patient passed away shortly thereafter (27). The patient in the present study is still alive, being treated with palliative care only, even with multiple bone lesions and hepatic involvement.

In conclusion, the current case report indicates that treatment with radiolabeled somatostatin analogues may be an effective alternative in similar cases where the neoplastic disease is inoperable and metastatic. This therapy was able to successfully control the disease, indicating that it may be a novel therapeutic strategy for this pathology.

References

- 1.Berger L, Luc G, Richard D. L'esthésioneuroépithéliome olfactif. Bull Assoc Franç Étude Cancer. 1924;13:410–421. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chirico G, Pergolizzi S, Mazziotti S, Santacaterina A, Ascenti G. Primary sphenoid esthesioneuroblastoma studied with MR. Clin Imaging. 2003;27:38–40. doi: 10.1016/S0899-7071(02)00533-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theilgaard SA, Buchwald C, Ingeholm P. Esthesioneuroblastoma: A Danish demographic study of 40 patients registered between 1978 and 2000. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003;123:433–439. doi: 10.1080/00016480310001295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson LD. Olfactory neuroblastoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3:252–259. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0125-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiro BJ, Escott EJ, Mchugh JB, Carrau RL. Bone invasion by an esthesioneuroblastoma mimicking fibrous dysplasia. Eur J Radiol. 2008;65:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharyya N, Thornton AF, Joseph MP, Goodman ML, Amrein PC. Successful treatment of esthesioneuroblastoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma with combined chemotherapy and proton radiation: Results in 9 cases. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:34–40. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900010038005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dulguero VP, Allal AS, Calcaterra TC. Esthesioneuroblastoma: A meta-analysis and review. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:683–690. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00558-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rinaldo R, Ferlito A, Shaha AR, Wei WI, Lund VJ. Esthesioneuroblastoma and cervical lymph node metastases: Clinical and therapeutic implications. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122:215–221. doi: 10.1080/00016480252814261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pickuth D, Heywang-Köbrunner SH, Speilman RP. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging features of olfactory neuroblastoma: An analysis of 22 cases. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1999;24:457–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1999.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zollinger LV, Wiggins RH, Cornelius RS, Phillips CD. Retropharyngeal lymph node metastasis from esthesioneuroblastoma: A review of the therapeutic and prognostic implications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1561–1563. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Vos FY, Willemse PH, de Vries EG. Successful treatment of metastatic esthesioneuroblastoma. Neth J Med. 2003;61:414–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadish S, Goodman M, Wang CC. Olfatory neuroblastoma. A clinical analysis of 17 cases. Cancer. 1976;37:1571–1576. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197603)37:3<1571::AID-CNCR2820370347>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chamberlain MC. Treatment of intracranial metastatic esthesioneuroblastoma. Cancer. 2002;95:243–248. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lund VJ, Howard D, Wei W, Spittle M. Olfactory neuroblastoma: Past, present, and future? Laryngoscope. 2003;113:502–507. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200303000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eich HT, Hero B, Staar S, Micke O, Seegenschmiedt H, Mattke A, Berthold F, Müller RP. Multimodality therapy including radiotherapy and chemotherapy improves event free survival in stage C esthesioneuroblastoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2003;179:233–240. doi: 10.1007/s00066-003-1089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz EM, Jr, Johnigan RH, Pero C, El-Naggar AK, Roberts DB, Barker JL, DeMonte F. Olfactory neuroblastoma: The 22-year experience at one comprehensive cancer center. 27. 2005:138–49. doi: 10.1002/hed.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uslu GH, Canyilmaz E, Zengin AY, Mungan S, Yoney A, Bahadir O, Gocmez H. Olfactory neuroblastoma: A case report. Oncol Letters. 2015;10:3651–3654. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodei L, Brand J Mueller, Baum RP, Pavel ME, Hörsh D, O'Dorisio MS, O'Dorisio TM, Howe JR, Cremonesi M, Kwekkeboom DJ, Zaknun JJ. The JOINT IAEA, EANM and SNMMI practical guidance on peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRNT) in neuroendocrine tumors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:800–816. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2330-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwekkeboom DJ, de Herder WW, Kam BL, van Eijck CH, van Essen M, Kooij PP, Feelders RA, van Aken MO, Krenning EP. Treatment with the radiolabeled somato- statin analog [177Lu-DOTA0, Tyr3]octreotate: Toxicity, efficacy, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2124–2130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Jong M, Breeman WA, Bernard BF, Bakker WH, Schaar M, van Gameren A, Bugaj JE, Erion J, Schmidt M, Srinivasan A, Krenning EP. 177Lu-DOTA (0), Tyr3 octreotate for somatostatin receptor targeted radionuclide therapy. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:628–633. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010601)92:5<628::AID-IJC1244>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morita A, Ebersold MJ, Olsen KD, Foote RL, Lewis JE, Quast LM. Esthesioneuroblastoma: Prognosis and management. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:706–714. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rostomily RC, Elias M, Deng M, Elias P, Born DE, Muballe D, Silbergeld DL, Futran N, Weymuller EA, Mankoff DA, Eary J. Clinical utility of somatostatin receptor scintigraphic imaging (Octreoscan) in esthesioneuroblastoma: A case study and survey of somatostatin receptor subtype expression. Head Neck. 2006;28:305–312. doi: 10.1002/hed.20356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virgolini I, Britton K, Buscombe J, Moncayo R, Paganelli G, Riva P. In- and Y-DOTA-lanreotide: Results and implication of the MAURITIUS trial. Semin Nucl Med. 2002;32:148–155. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2002.31565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitzek MM, Thornton AF, Varvares M. Neuroendocrine tumors of the sinonasal tract. Results of a prospective study incorporating chemotherapy, surgery, and combined proton-photon radiotherapy. Cancer. 2002;94:2623–2634. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howell MC, Branstetter BF, Snyderman CH. Patterns of Regional Spread for Esthesioneuroblastoma. AJNR AM J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:929–933. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajesh, Shekhar S, Madhavan S. Esthesioneuroblastoma with hepatic and splenic metastasis. Indian J Radiol Imag. 2003;13:219–222. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makis W, McCann K, McEwan A. Esthesioneuroblastoma (olfactory neuroblastoma) treated with 111In-octreotide and 177Lu-DOTATATE PRRT. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;4:317–321. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]