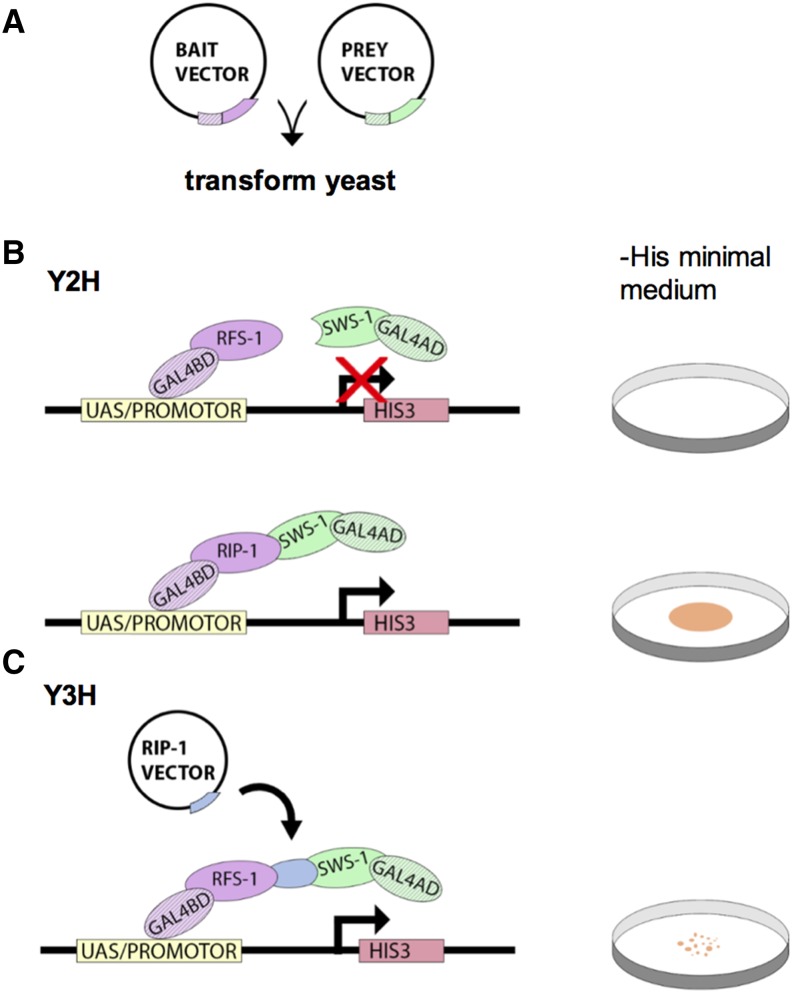

Figure 3.

Yeast hybrid experiments detect protein–protein interactions. (A) In yeast hybrid screens, the budding yeast S. cerevisiae are cotransformed with a bait vector and a prey vector, which encode a protein of interest fused to the BD or the AD of the Gal4 transcription factor, respectively. (B) The yeast strain is typically auxotrophic, meaning that it is unable to synthesize an essential nutrient, in this case the amino acid histidine. Transformed yeast plated on a medium lacking this nutrient (i.e., −His minimal medium; see Petri dish schematic on right) will not grow unless interactions between bait and prey proteins bring the BD and AD in close enough proximity to form a functional Gal4 transcription factor. This allows for transcription of HIS3, an enzyme involved in histidine biosynthesis. Thus, growth on −His medium serves as a marker for bait/prey interactions. Various combinations of bait and prey vectors can be used to effectively assess a multitude of protein–protein interactions. From these Y2H assays, the authors determined that SWS-1 interacts with RIP-1 but not RFS-1. (C) Y3H assays are similar, with the addition of a vector encoding a third gene of interest (RIP-1 vector). The transcription product of this gene may interact with both the bait and prey, bridging the interaction between the BD and AD. In this study, RIP was shown to bridge RFS-1 and SWS-1. Growth of the yeast was less robust (as indicated by Petri dish schematic on right), suggesting that the three-protein complex was less stable than the RIP-1/SWS-1 complex.