Abstract

The coexistence of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) and gastric cancer is relatively high, and its prognosis is controversial due to the complex and variant kinds of presentation. Thus, the present study aimed to explore the clinicopathological features and prognostic factors of gastric GIST with synchronous gastric cancer.

From May 2010 to November 2015, a total of 241 gastric GIST patients were retrospectively enrolled in the present study. The patients with coexistence of gastric GIST and gastric cancer were recorded. The clinicopathological features and prognoses of patients were analyzed.

Among 241 patients, 24 patients had synchronous gastric cancer (synchronous group) and 217 patients did not (no-synchronous group). The synchronous group presented a higher percentage of elders (66.7% vs 39.6%, P = 0.001) and males (87.5% vs 48.4%, P < 0.001) than the no-synchronous group. The tumor diameter, mitotic index, and National Institutes of Health degree were also significantly different between the 2 groups (all P < 0.05). The 5-year disease-free survival and disease-specific survival rates of synchronous group were significantly lower than those of no-synchronous group (54.9% vs 93.5%, P < 0.001; 37.9% vs 89.9%, P < 0.001, respectively). However, the 5-year overall survival rates between synchronous and gastric cancer groups were comparable (37.9% vs 57.6%, P = 0.474).

The coexistence of gastric GIST and gastric cancer was common in elder male patients. The synchronous GIST was common in low-risk category. The prognosis of gastric GIST with synchronous gastric cancer was worse than that of primary-single gastric GIST, but was comparable with primary-single gastric cancer.

Keywords: feature, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, prognosis, synchronous gastric cancer

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common mesenchymal tumor of the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract,[1] which accounts for nearly 2.2% of GI malignancies,[2] with an estimated incidence of 10 to 20 per million.[3] Stomach (60%–70%) is the most frequent site of GIST, followed by small intestine, colon and rectum, and esophagus.[4] Recently, increasing literatures demonstrated the evidence of coexistence of GIST and other malignancies. It is reported that the most common synchronous malignancy is gastrointestinal (GI) carcinoma, which is mainly located in the stomach (47%).[5]

The detected synchronous GIST was mainly diagnosed incidentally during surgery of other malignancies or during postoperative pathologic examinations of specimens. These GISTs were usually small and asymptomatic. But it is reported that few small GISTs, which were diagnosed as nonmalignant, may exhibit potential of malignant transformation.[6–8] The clinical management and treatment of concurrence of GIST and other malignancies is complex due to its various kinds of presentation.[9]

The previous reports on coexistence of gastric GIST and gastric cancer (synchronous group) are limited to case reports or small samples compared with the primary-single gastric GIST (no-synchronous group). However, the clinical treatments and outcomes of patients among synchronous group, no-synchronous group, and primary-single gastric cancer are still controversial. The role of gastric cancer in prognosis of gastric GIST patients with synchronous gastric cancer was unclear. Thus, the present study aimed to explore the clinicopathologic features and prognoses of synchronous group compared with no-synchronous group and primary-single gastric cancer.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patients

From May 2010 to November 2015, a total of 312 gastric GIST patients were diagnosed and accepted treatment in Xijing Hospital, the Fourth Military Medical University. The exclusion criteria were listed as follows: accompanied with malignancies other than gastric cancer, with preoperative distant metastasis, not receive R0 resection, with preoperative imatinib therapy, and with incomplete follow-up records. Finally, a total of 241 gastric GIST patients were enrolled in this study, of which 24 patients were diagnosed with synchronous gastric cancer (synchronous group) and 217 were not (no-synchronous group). The exclusion criteria of gastric cancer were listed as follows: accompanied with other malignancies, with distant metastasis, not receive R0 resection, and with preoperative chemotherapies. Finally, a total of 3385 primary-single gastric cancer patients were enrolled in the present study.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xijing Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before surgery.

2.2. Surgery

Patients received routine examinations including abdominal computed tomography, abdominal ultrasound, and gastroscopy in order to diagnose the cancer and assess the metastasis before surgery. Curative surgical resections were performed according to the clinical and pathological features of cancer (GIST: tumor size and location; gastric cancer: tumor size, location, and tumor invasion). Surgical procedures include total gastrectomy, proximal gastrectomy, distal gastrectomy, and endoscopic submucosal resection. Lymphadenectomy was routinely performed for gastric cancer according to the NCCN guideline.[10] The GISTs were classified as very low, low, intermediate, and high risk according to the modified protocol of National Institutes of Health (NIH) reported by Joensuu.[11]

2.3. Clinicopathological data

All clinicopathological data were retrospectively listed as follows: for GIST: age, gender, blood type, location of GIST, tumor size, morphology, mitotic index, Ki-67, tumor bleeding, tumor ulceration, tumor necrosis, mutational status, immunohistochemistry (CD117, CD34, and DOG-1), NIH risk category, and adjuvant therapy; for gastric cancer: age, gender, location of gastric cancer, tumor size, histologic type, tumor invasion, lymph node metastasis, and tumor-node-metastasis staging system (TNM) stage. The preoperative symptoms included abdominal pain, abdominal distention, bleeding, and other complications (fatigue, cough, dyspnea, fever, and vomit).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data were processed using SPSS 22.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Numerical variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median. Discrete variables were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Risk factors for survival identified by univariate were further assessed by multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression model. Disease-free survival (DFS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between curves were compared using log-rank test. P values were considered to be statistically significant at the 5% level.

3. Results

3.1. General features between synchronous and no-synchronous groups

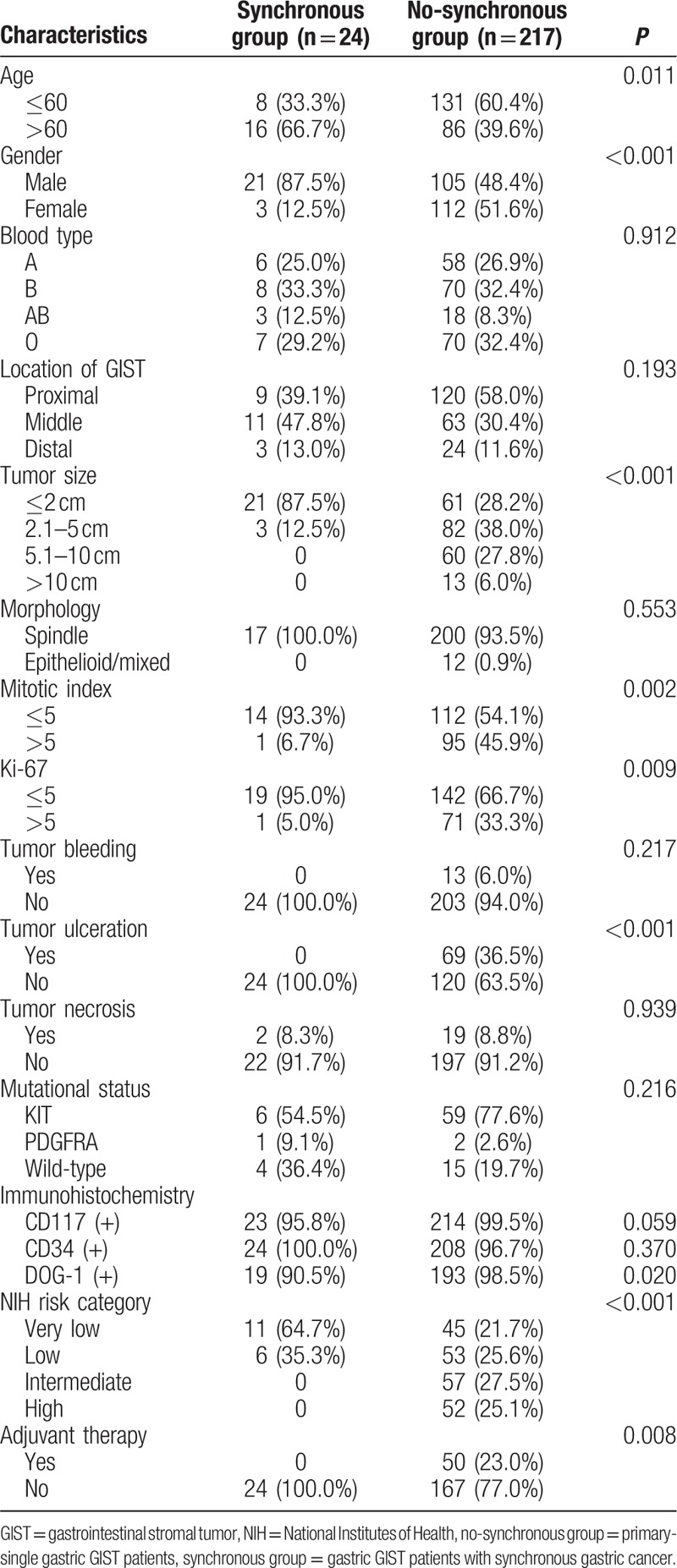

Clinicopathologic features between synchronous and no-synchronous groups are summarized in Table 1. The entire cohort comprised 241 gastric GIST patients and included 126 males and 115 females, with a mean age of 57.5 years and a median age of 58 years. Among the 241 enrolled patients, 24 were diagnosed as synchronous group and 217 were no-synchronous group.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinicopathological features between patients of synchronous and no-synchronous groups.

The synchronous group presented higher percentage of elders (>60 years, 66.7% vs 39.6%, P = 0.011) and males (87.5% vs 48.4%, P < 0.001) than those of no-synchronous group. Tumor diameter of synchronous group was significantly smaller than that of no-synchronous group (P < 0.001). The mitotic index of tumors in synchronous group was lower (<5/50 HPF) than that of no-synchronous group (93.9% vs 54.1%, P = 0.002). Moreover, the synchronous group had lower Ki-67 index, a higher percentage of tumor ulceration, a lower expression rate for DOG-1(+), and lower NIH risk category (all P < 0.05). All of the 24 cases in the synchronous group did not receive postoperative adjuvant therapy of Imatinib mesylate (P = 0.008). No statistical significance was detected in regard to blood type, location of GIST, morphology, tumor bleeding, tumor necrosis, mutational status, and the positive expression of CD117 and CD34 between the groups (P > 0.05).

3.2. Preoperative symptoms between synchronous and no-synchronous groups

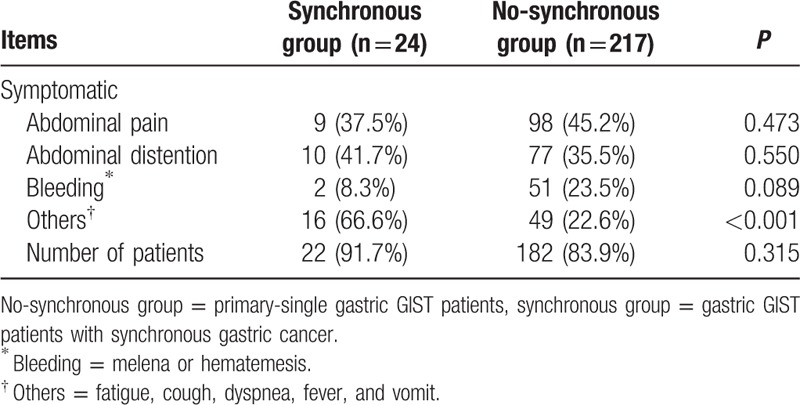

As showed in Table 2, the preoperative symptomatic rate of patients between synchronous and no-synchronous groups had no statistical difference (91.7% vs 83.9%, P = 0.315). Abdominal pain, abdominal distention, and bleeding (melena or hematemesis) were comparable between the 2 groups (all P > 0.05). The total incidence of other symptoms including fatigue, cough, dyspnea, fever, and vomit were significantly higher in synchronous group than that of no-synchronous group (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Preoperative symptoms of patients between synchronous and no-synchronous groups.

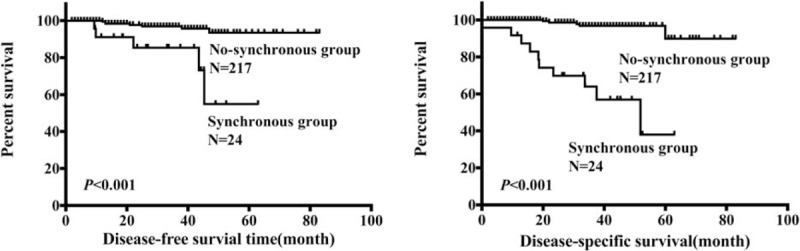

3.3. Survival between synchronous and no-synchronous groups

Survival was analyzed in 241 gastric GIST patients with range of follow-up from 0.1 to 83.0 months (median, 31.7 months), and 15 patients died from the entire cohort. The 3- and 5-year DFS of synchronous group were significantly lower than those of no-synchronous group (85.4% vs 96.9%, P = 0.009; 54.9% vs 93.5%, P < 0.001, respectively, Fig. 1A). The 3- and 5-year DSS of synchronous group were significantly lower than those of no-synchronous group (64.0% vs 96.8%, P < 0.001, 37.9% vs 89.9%, P < 0.001, respectively, Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Comparison of disease-free survival and disease-specific survival of synchronous and no-synchronous groups.

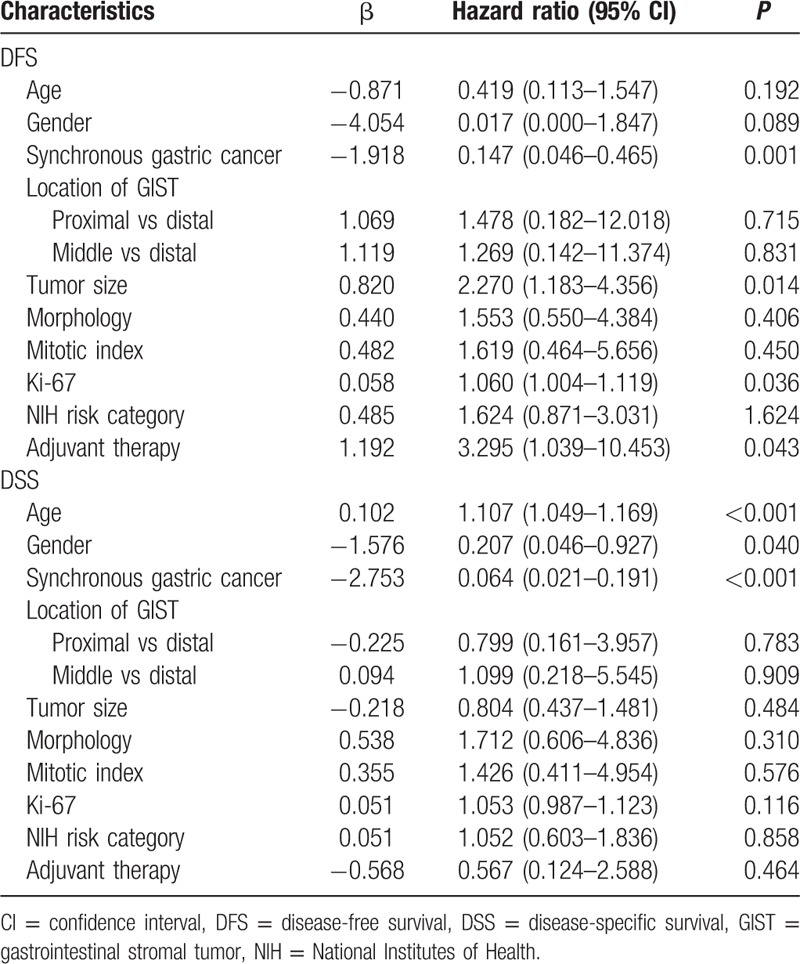

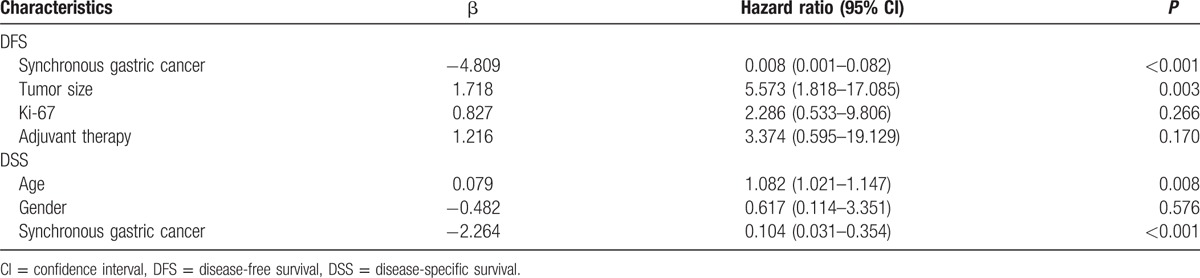

The presence of synchronous gastric cancer, tumor size, Ki-67, and adjuvant therapy was associated with poorer DFS, and the presence of age, gender, and synchronous gastric cancer was associated with poorer DSS according to the univariate analysis (all P < 0.05, Table 3). Moreover, multivariate analysis showed that synchronous gastric cancer and tumor size were the independent predictor of DFS, and age and synchronous gastric cancer were the independent predictor of DSS (all P < 0.05, Table 4).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of variables associated with DFS and DSS in patients with gastric GIST (n = 241).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for DFS and DSS in patients with gastric GIST (n = 241).

3.4. Comparison between synchronous and gastric cancer groups

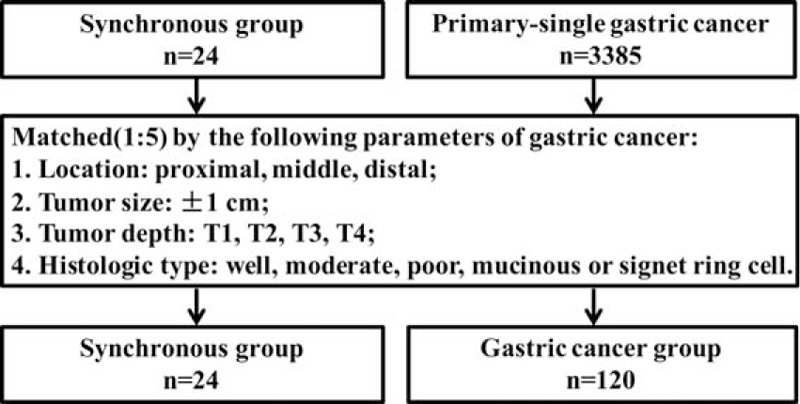

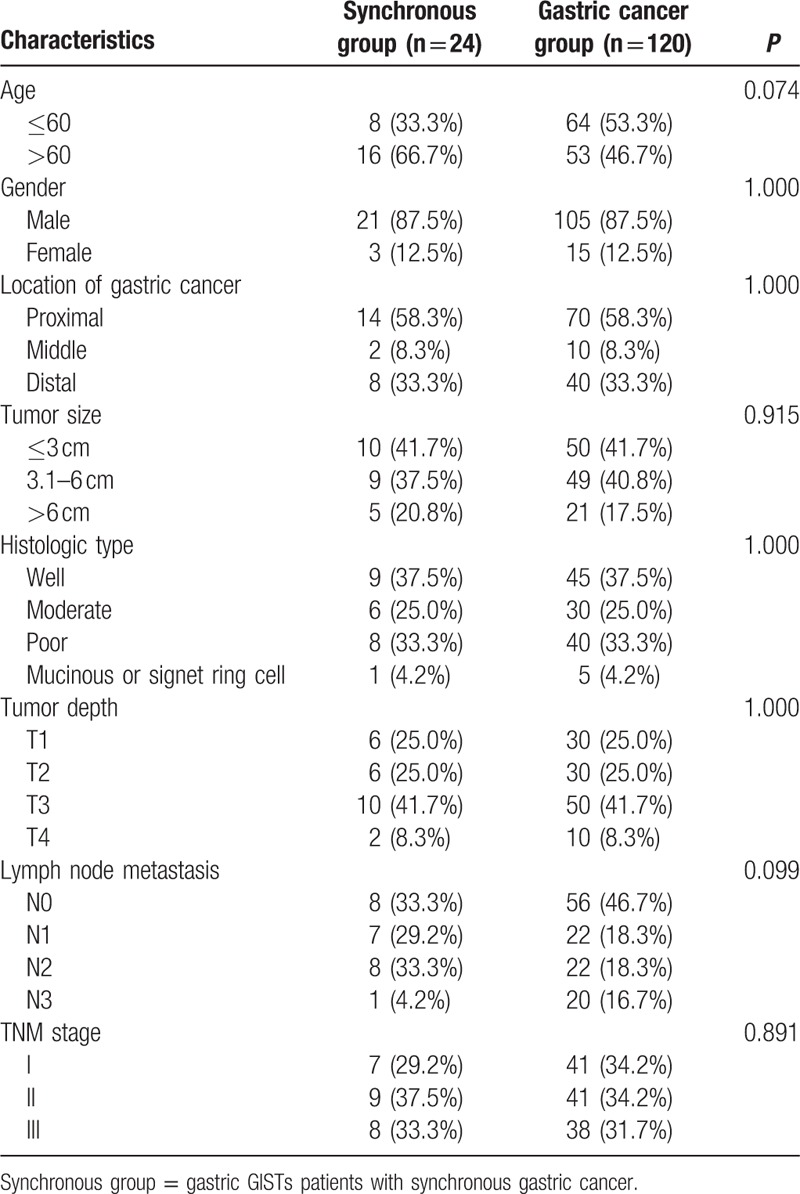

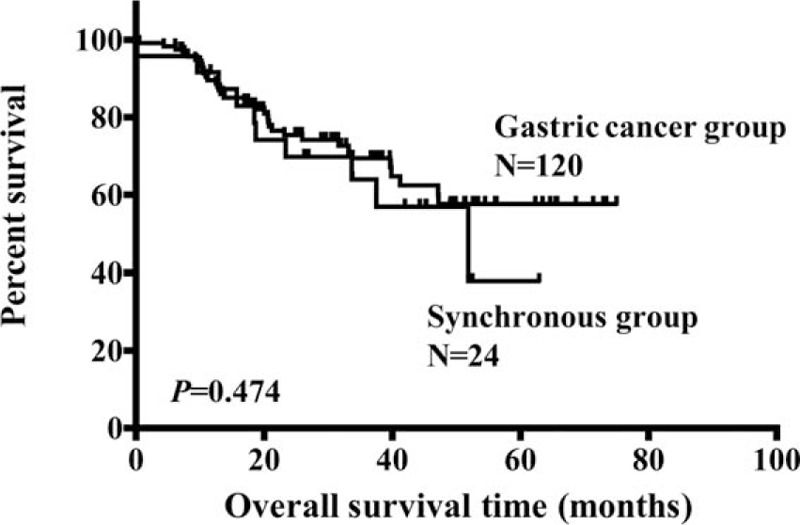

Next, in order to further analyze the prognosis between synchronous group and primary-single gastric cancer, patients from the 2 groups were compared by matching the parameters of gastric cancer including location, tumor size, tumor depth, and histologic type, which is shown in Fig. 2 as a flowchart. As shown in Table 5, finally, a total of 120 gastric cancer patients were matched (1:5) out as the gastric cancer group. There was no significant difference in age, gender, location, tumor size, histologic type, tumor depth, lymph node metastasis, and TNM stage when they were compared between the 2 groups. The Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that the 5-year overall survival rates of the synchronous and gastric cancer group were comparable (37.9% vs 57.6%, P = 0.474, Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of match strategy between synchronous group and primary-single gastric cancer patients.

Table 5.

Comparison of clinicopathological features of matched patients between synchronous and gastric cancer groups.

Figure 3.

Comparison of overall survival of matched patients between synchronous and gastric cancer group.

4. Discussion

The incidence of GIST with synchronous malignancies was reported in a range of 2.95% to 33% in previous studies.[5,12–15] A previous meta-analysis reviewed 14 literatures and demonstrated that approximately 9.2% of GIST patients suffered a second primary carcinoma. Among these synchronous cancers, GI malignancies account for 4.7% (228/4813) of GIST patients.[5] This present retrospective study showed that the coexistence of gastric GIST and gastric cancer occurred in a higher rate of almost 9.96% (24/241) among gastric GIST patients. Furthermore, we found that the presence of synchronous gastric cancer was both an independent prognostic factor of DFS and DSS for gastric GISTs.

Previous studies indicated that the coexistence of GIST and malignancies predominantly occurred in elders.[16] Shen et al[9] reported that the rate of synchronous malignancies was 37.89% in elderly (>60 years) GIST patients, which was higher than the common incidence range mentioned above. With an agreement in our series, almost 66.7% (16/24) patients were older than 60 years in synchronous group. The multivariate analysis showed that age was an independent prognostic factor for DSS. However, some evidence indicates that age was not associated with survival for GIST patients.[9] Tham et al[17] demonstrated that patients older than 65 years showed a comparable outcome as younger patients. The role of age in GIST remains to be further investigated. Furthermore, male was also presented a high rate in the synchronous group in our study. In addition, thus the elderly male patients with GI cancers should be focused on in clinic.

The preoperative diagnosis of synchronous GIST with other malignancies is particularly difficult. Zhang et al[18] reported that only 12.5% (4/32) patients were preoperatively diagnosed with concurrent digestive tract carcinomas. The preoperative imaging examinations including computed tomography and endoscopy are routinely used to differentiate GIST.[19] In patients with synchronous gastric GIST and gastric cancer, the manifestations of gastric GIST are often masked by the symptoms of gastric cancer due to the small size of synchronous gastric GIST.[20] In addition, GISTs may be misdiagnosed as lymph node metastases during surgery.[21] In fact, the preoperative diagnostic rate of synchronous gastric GIST with gastric cancer was only 2.4% (1/42) as reported by Lin et al.[20] In the present study, with an agreement with previous results, the preoperative symptomatic rate of patients in synchronous group was comparable with that of no-synchronous group, and the preoperative diagnostic rate was 0% (0/24). In consideration of the incidence above, the actual preoperative diagnostic rate of synchronous gastric GIST with gastric cancer is extremely underestimated.

It is reported that the proliferation of small GIST is low.[22] The tumor size of synchronous GIST with other malignancies is usually smaller than 2 cm.[15,21,23] Yan et al[6] described 15 gastric GISTs with synchronous gastric cancer, among which 14 cases were smaller than 2 cm in size. Similar to these studies, 87.5% (21/24) of patients in synchronous group in the present study were smaller than 2 cm with an overall mean size of 1.19 ± 1.08 cm. Moreover, in synchronous group, the mitotic index of 93.3% (14/15) patients was less than 5/50 HPF, and the Ki-67 index of 95.0% (19/20) patients was less than 5%. With the agreement of Yan et al[6] and Lin et al,[20] the total cases of patients in synchronous group were classified as low or very low risk. Actually, small GIST is thought to have a benign prognosis, as there was no disease-specific mortality among 116 GISTs whose lesions were less than 2 cm in Mittinen study.[24] In the present study, the recurrent rate of GIST-specific in synchronous group was 0% (0/24). Even so, some surgeons recommended an en bloc or additional resection for the coexistence of GIST and other neoplasms due to their imprecise prediction of malignant transformation.[25] In addition, the complex execution of second operation for malignancies also make surgeons tend to remove the incidentally discovered GISTs during surgery for other neoplasms.[6]

A previous study indicated that the majority of synchronous GISTs with other malignancies expressed CD117 and CD34.[6] On the contrary, Lin et al[20] reported that gastric GIST with synchronous gastric cancer presented a lower expression rate of CD117 and CD34. Interestingly, our study found that only the expression rate of DOG-1 was significantly lower in the synchronous group. Therefore, role of immunohistochemistry including CD117, CD34, and DOG-1 in the coexistence of synchronous gastric GIST and gastric cancer remains to be further investigated.

Previously, the 5-year overall survival rate of gastric GIST that underwent R0 resection was reported in a range of 42% to 75.9%.[26,27] The improvement of survival rate benefits from the modified surgical skill and the application of imatinib mesylate. However, gastric GIST patients with synchronous gastric cancer showed a lower 5-year overall survival rate of 57.8% with a median survival time of 36 months, as reported by Liu et al.[25] It is reported that the 5-year overall survival rate of gastric GIST patients with synchronous gastric cancer was significantly lower than that of gastric GIST patients without synchronous gastric cancer.[20] With an agreement in our study, the 5-year DFS and DSS of synchronous group were also lower than those of no-synchronous group. In order to further analyze the prognosis between synchronous group and primary-single gastric cancer, patients from the 2 groups were compared by matching the characteristics of gastric cancer including location, tumor size, tumor depth, and histologic type. The results showed that the overall survival rate of patients between synchronous group and gastric cancer group were comparable. The disease progression and disease-specific death of synchronous group were both influenced or caused by gastric GIST and gastric cancer. This result indicated that the poor DFS of synchronous group might mainly be caused by gastric cancer, which meant that GIST itself had little effect on the clinical outcome of synchronous GIST patients.

There are some limitations in the present study. First, it is a retrospective study. Second, the sample size was not large enough, which will lead to statistical bias. Third, the gastric GIST with synchronous gastric cancer was not compared with other synchronous GI cancers.

5. Conclusion

The coexistence of gastric GIST and gastric cancer was common in elder male patients. The synchronous GIST was common in small size, low mitotic index, and low-risk category. The prognosis of gastric GIST with synchronous gastric cancer was worse than that of primary-single gastric GIST, but was comparable with primary-single gastric cancer.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: DFS = disease-free survival, DSS = disease-specific survival, GI = gastrointestinal, GIST = gastrointestinal stromal tumor, NIH = National Institutes of Health.

ZL, SL, and GZ have contributed equally to the article.

Funding/support: This study was supported in part by grants from the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (no. 31100643, 31570907, 81572306, and XJZT12Z03).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Feng F, Liu Z, Zhang X, et al. Comparison of endoscopic and open resection for small gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Transl Oncol 2015; 8:504–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheppard K, Kinross KM, Solomon B, et al. Targeting PI3 kinase/AKT/mTOR signaling in cancer. Crit Rev Oncog 2012; 17:69–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzen CY, Wang JH, Huang YJ, et al. Incidence of gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a retrospective study based on immunohistochemical and mutational analyses. Dig Dis Sci 2007; 52:792–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao X, Yue C. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Gastrointest Oncol 2012; 3:189–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agaimy A, Wunsch PH, Sobin LH, et al. Occurrence of other malignancies in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Semin Diagn Pathol 2006; 23:120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan Y, Li Z, Liu Y, et al. Coexistence of gastrointestinal stromal tumors and gastric adenocarcinomas. Tumour Biol 2013; 34:919–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maiorana A, Fante R, Maria Cesinaro A, et al. Synchronous occurrence of epithelial and stromal tumors in the stomach: a report of 6 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000; 124:682–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawanowa K, Sakuma Y, Sakurai S, et al. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum Pathol 2006; 37:1527–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen C, Chen H, Yin Y, et al. Synchronous occurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumors and other digestive tract malignancies in the elderly. Oncotarget 2015; 6:8397–8406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ajani JA, Bentrem DJ, Besh S, et al. Gastric cancer, version 2.2013: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013; 11:531–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol 2008; 39:1411–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hechtman JF, DeMatteo R, Nafa K, et al. Additional primary malignancies in patients with Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST): a clinicopathologic study of 260 patients with molecular analysis and review of the literature. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22:2633–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandurengan RK, Dumont AG, Araujo DM, et al. Survival of patients with multiple primary malignancies: a study of 783 patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Ann Oncol 2010; 21:2107–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreira SS, Werutsky G, Toneto MG, et al. Synchronous gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) and other primary cancers: case series of a single institution experience. Int J Surg (London, England) 2010; 8:314–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wronski M, Ziarkiewicz-Wroblewska B, Gornicka B, et al. Synchronous occurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumors and other primary gastrointestinal neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12:5360–5362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nilsson B, Bumming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era—a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer 2005; 103:821–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tham CK, Poon DY, Li HH, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour in the elderly. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2009; 70:256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang P, Deng R, Xia Z, et al. Concurrent gastrointestinal stromal tumor and digestive tract carcinoma: a single institution experience in China. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8:21372–21378. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gold JS, Dematteo RP. Combined surgical and molecular therapy: the gastrointestinal stromal tumor model. Ann Surg 2006; 244:176–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin M, Lin JX, Huang CM, et al. Prognostic analysis of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor with synchronous gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2014; 12:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liszka L, Zielinska-Pajak E, Pajak J, et al. Coexistence of gastrointestinal stromal tumors with other neoplasms. J Gastroenterol 2007; 42:641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rossi S, Gasparotto D, Toffolatti L, et al. Molecular and clinicopathologic characterization of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) of small size. Am J Surg Pathol 2010; 34:1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai R, Ren G, Wang DB. Synchronous adenocarcinoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19:3117–3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol 2005; 29:52–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu YJ, Yang Z, Hao LS, et al. Synchronous incidental gastrointestinal stromal and epithelial malignant tumors. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15:2027–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong NA, Young R, Malcomson RD, et al. Prognostic indicators for gastrointestinal stromal tumours: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 108 resected cases of the stomach. Histopathology 2003; 43:118–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang H, Liu YX, Zhan ZL, et al. Different sites and prognoses of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: report of 187 cases. World J Surg 2010; 34:1523–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]