Abstract

Background

Mast cells are significantly involved in IgE-mediated allergic reactions; however, their roles in health and disease are incompletely understood.

Objective

We aimed to define the proteome contained in mast cell releasates upon activation to better understand the factors secreted by mast cells that are relevant to the contribution of mast cells in diseases.

Methods

Bone marrow derived-cultured mast cells (BMCMCs) and peritoneal cell-derived mast cells (PCMCs) were used as “surrogates” for mucosal and connective tissue mast cells, respectively, and their releasate proteomes were analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Results

Our studies showed that BMCMCs and PCMCs produced substantially different releasates following IgE-mediated activation. Moreover, we observed that the transglutaminase, coagulation factor XIIIA, was one of the most abundant proteins contained in the BMCMC releasates. Mast cell-deficient mice exhibited increased FXIIIA plasma and activity levels as well as reduced bleeding times, indicating that mast cells are more efficient in their ability to down-regulate FXIIIA than in contributing to its amounts and functions in homeostatic conditions. We found that human chymase and mouse mast cell protease (mMCP)-4 (the mouse homologue of human chymase) had the ability to reduce FXIIIA levels and function via proteolytic degradation. Moreover, we found that chymase deficiency led to increased FXIIIA amounts and activity, as well as reduced bleeding times in homeostatic conditions and during sepsis.

Conclusions

Our study indicates that the mast cell protease content can shape its releasate proteome. Moreover, we found that chymase plays an important role in the regulation of FXIIIA via proteolytic degradation.

Keywords: Mast cells, proteases, chymase, proteomics

INTRODUCTION

Mast cells are hematopoietic progenitor-derived, granule-containing immune cells that are widely distributed in tissues that interact with the external environment, such as the skin and mucosal tissues. Although it is well known that mast cells are significantly involved in IgE-mediated allergic reactions, recent studies have shown that mast cells and their granule proteases have pleiotropic regulatory roles in other immunological responses and diseases, such as in bacterial and parasite infections, sepsis, auto-immune disease, and cancer.1 Many of these studies, however, were biased to investigate mouse models in which mast cells were hypothesized to play key roles based on in vitro studies or conditions in which mast cell numbers or their mediators were increased, suggesting that our understanding of the contribution of mast cells to health and disease is limited. In this study, we adopted an unbiased approach with the potential to provide a more comprehensive assessment of how mast cells may influence biological processes by characterizing mast cell releasate proteomes via mass spectrometry analysis.

Mast cells express protease profiles that vary amongst species and different mast cell subsets. In humans, mast cells either express tryptase (α and β) only (known as the MCT subclass) or tryptase, chymase, and mast cell carboxypeptidase A (CPA) (known as the MCTC subclass). In mice, mast cells are divided into connective tissue (CTMC) and mucosal mast cell (MMC) subtypes. CTMCs predominantly express the β-chymase, mouse mast cell protease 4 [mMCP-4] and the α-chymase, mMCP-5, whereas MMCs predominantly express two different β-chymases, mMCP-1 and mMCP-2. Additionally, in the C57BL/6 mouse background, CTMCs also express a tetrameric tryptase (mMCP-6) as well as CPA. 2 We and others have shown that mast cell proteases can cleave certain mediators released by mast cells into inactive or active fragments. For example, we reported that mMCP-4, the mouse homolog of human chymase in substrate specificity, 3 prevents hyper-inflammation in severe sepsis via proteolytic degradation of tumor necrosis factor (TNF). 4 Consequently, it is important to understand how mast cell phenotypes and their protease content may shape their mediator release profile upon activation. Herein, we characterized the releasates generated by bone marrow derived-cultured mast cells (BMCMCs) and peritoneal cell-derived mast cells (PCMCs) following IgE-mediated activation as “surrogates” for MMCs and CTMCs, respectively.5,6

Our proteomics studies indicate that BMCMCs and PCMCs produced substantially different releasates. As a specific example, we observed that the transglutaminase, coagulation factor XIIIA (FXIIIA), was one of the most abundant proteins in the IgE-mediated BMCMC releasate. In contrast, the PCMC releasate did not contain FXIIIA. Therefore, we investigated the involvement of CTMC-specific proteases in the down-regulation of FXIIIA, and we observed that mast cell chymase could proteolytic degrade FXIIIA and diminish its function during homeostatic and septic states.

METHODS

For detailed methods, including the mice used, experimental protocols and procedures, and statistical analysis, please see the Methods section in this article’s Online Repository www.jacionline.org.

RESULTS

Proteome profiling of mast cell-releasates

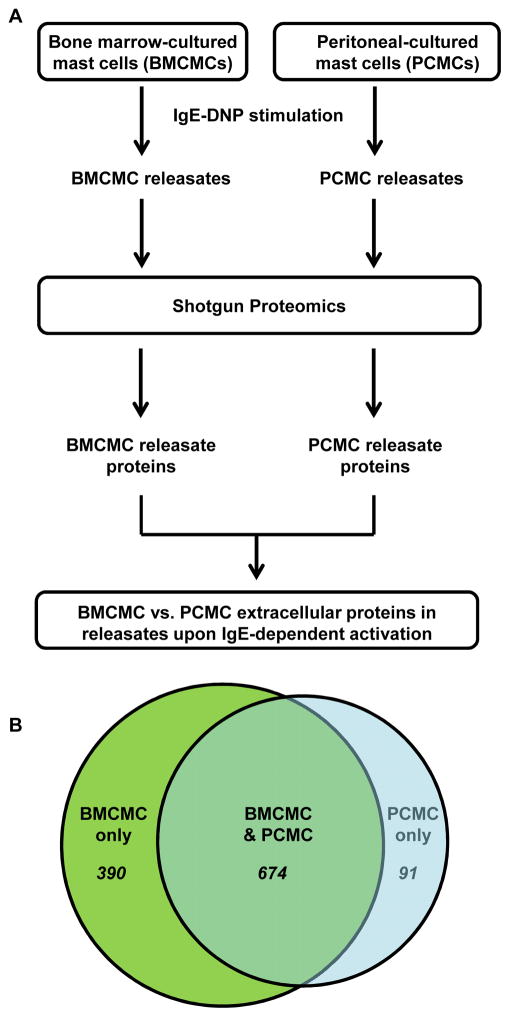

To define the BMMC and PCMC releasates following IgE-mediated activation, we utilized a mass spectrometry shotgun proteomics approach. Specifically, IgE-DNP sensitized BMCMCs and PCMCs were stimulated with DNP-HSA antigen for 6h. Then, the supernatants were collected, concentrated, and subjected to LC-MS/MS to identify the IgE-mediated differentially produced proteins from these MCs (Fig. 1A). We identified 91 proteins that were unique to PCMCs (Table 1 and Suppl. Table 1), 390 proteins that were unique to BMCMCs (Table 2 and Suppl. Table 2), and 674 proteins that were extracellularly produced by both BMCMCs and PCMCs (Table 3 and Suppl. Table 3) (Fig. 1B). We associated the proteins identified in the releasates with functional annotations. By gene ontology (GO) analysis, the commonly enriched biological process categories in the BMCMC and PCMC releasates were linked to metabolic processes (e.g., carbohydrate/protein metabolism and glycolysis) as well as intracellular protein trafficking, protein folding, cell structure and motility, and endocytosis (Table 3 + Suppl. Table 4). Synthesis of newly formed mediators and mediator secretion are two main mast cell functions upon activation that may require the metabolic and actin cytoskeleton remodeling processes observed in our GO analysis. Processes associated with protein alteration, such amino acid, protein metabolism and proteolysis were the main processes found amongst the unique proteins contained in the PCMC releasates (Suppl. Table 5). The enriched categories from the unique BMCMC releasates (not found in the PCMC releasates) were associated with blood clotting, immune response regulation (e.g., cytokine and chemokine mediated signaling pathways), and immunity and defense (Suppl. Table 6). These data suggest not only that BMCMCs produce factors related to immune response regulation but also that PCMCs either do not produce these factors or they are more efficient in their down-regulation via proteolysis.

Figure 1. Differentially produced extracellular proteins from bone marrow compared with peritoneal derived mast cells.

(A) A schematic overview of the approach used to define the releasates generated by BMCMCs and PCMCs following IgE-mediated activation. (B) A Venn diagram showing the number of shared and exclusive proteins amongst the BMCMC and PCMC releasates.

Table 1. Top 20 unique PCMC releasate proteins.

Ex-vivo IgE-activated mouse peritoneal-derived mast cell extracellular proteins that were not observed in the IgE-activated bone marrow-derived mast cell supernatants (top 20 proteins identified, according to spectral counts).

| Gene name | UniProt ID | Uniprot description | Normalized PCMC spectral counts (avg.) | Normalized BMCMC spectral counts (avg.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mcpt4 | MCPT4_MOUSE | Mast cell protease 4 (mMCP-4) | 62.34 | 0.81 |

| Ahnak | E9Q616_MOUSE | Protein Ahnak | 20.38 | 0.81 |

| Flna | FLNA_MOUSE | Filamin-A | 19.54 | 0.00 |

| Mcpt1 | Q496V0_MOUSE | Mast cell protease 1 | 15.14 | 0.00 |

| Aoah | AOAH_MOUSE | Acyloxyacyl hydrolase | 12.82 | 0.40 |

| Cpq | CBPQ_MOUSE | Carboxypeptidase Q | 12.66 | 0.00 |

| Galc | GALC_MOUSE | Galactocerebrosidase | 12.27 | 0.28 |

| Ecm1 | ECM1_MOUSE | Extracellular matrix protein 1 | 12.17 | 0.00 |

| Ddah2 | DDAH2_MOUSE | N(G),N(G)-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 | 8.65 | 0.81 |

| Papss2 | PAPS2_MOUSE | Bifunctional 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthase 2 | 8.64 | 0.00 |

| Lap3 | AMPL_MOUSE | Cytosol aminopeptidase | 8.56 | 0.00 |

| Syngr1 | SNG1_MOUSE | Synaptogyrin-1 | 7.53 | 0.81 |

| Ckb | KCRB_MOUSE | Creatine kinase B-type | 7.06 | 0.00 |

| Aars | SYA_MOUSE | Alanine--tRNA ligase, cytoplasmic | 6.45 | 0.13 |

| Rbp1 | Q58EU7_MOUSE | Rbp1 protein | 6.38 | 0.00 |

| Ide | IDE_MOUSE | Insulin-degrading enzyme | 6.19 | 0.27 |

| Kv2a7 | KV2A7_MOUSE | Ig kappa chain V-II region 26–10 | 5.89 | 0.67 |

| Ptprg | PTPRG_MOUSE | Receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase gamma | 5.60 | 0.00 |

| Prkar2b | KAP3_MOUSE | cAMP-dependent protein kinase type II-beta regulatory subunit | 5.50 | 0.14 |

| Pacsin2 | Q3TDA7_MOUSE | Protein kinase C and casein kinase substrate in neurons 2, | 5.04 | 0.68 |

Table 2. Top 20 unique BMCMC releasate proteins.

Ex-vivo IgE-activated mouse bone marrow-derived mast cell extracellular proteins that were not observed in the IgE-activated peritoneal-derived mast cell supernatants (top 20 proteins identified, according to spectral counts).

| Gene name | UniProt ID | Uniprot description | Normalized PCMC spectral counts (avg.) | Normalized BMCMC spectral counts (avg.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scin | ADSV_MOUSE | Adseverin | 0.26 | 66.88 |

| Mcpt8 | Q3UWB6_MOUSE | Mast cell protease 8 | 0.00 | 41.26 |

| Akr1c18 | Q3U538_MOUSE | Aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C18 | 0.00 | 33.53 |

| Napsa | Q3U7H1_MOUSE | Putative uncharacterized protein | 0.00 | 29.36 |

| Jak1 | JAK1_MOUSE | Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK1 | 0.82 | 22.41 |

| F13a1 | F13A_MOUSE | Coagulation factor XIII A chain | 0.00 | 21.94 |

| Hist1h2af | H2A1F_MOUSE | Histone H2A type 1-F | 0.26 | 21.19 |

| Il4ra | Q3U905_MOUSE | Interleukin 4 receptor, alpha | 0.26 | 19.09 |

| Hist1h2bb | H2B1B_MOUSE | Histone H2B type 1-B | 0.00 | 19.00 |

| Ifitm1 | IFM1_MOUSE | Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 1 | 0.00 | 18.63 |

| Anxa2 | Q542G9_MOUSE | Annexin | 0.27 | 18.36 |

| Stat5a | Q9JIA0_MOUSE | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5A | 0.00 | 17.14 |

| Ccl6 | SY06_MOUSE | C-C motif chemokine 6 | 0.00 | 16.35 |

| Upp1 | UPP1_MOUSE | Uridine phosphorylase 1 | 0.00 | 14.67 |

| Ctsg | Q059V7_MOUSE | Cathepsin G | 0.58 | 14.66 |

| Myo1g | MYO1G_MOUSE | Unconventional myosin-Ig | 0.00 | 12.29 |

| Tgfbr1 | Q4FJL1_MOUSE | Tgfbr1 protein | 0.86 | 11.64 |

| Atp6v0a1 | VPP1_MOUSE | V-type proton ATPase 116 kDa subunit a isoform 1 | 0.58 | 11.15 |

| Tmem59 | TMM59_MOUSE | Transmembrane protein 59 | 0.56 | 10.64 |

| Aldh9a1 | AL9A1_MOUSE | 4-trimethylaminobutyraldehyde dehydrogenase | 0.58 | 10.11 |

Table 3. Top 20 shared PCMC and BMCMC releasate proteins.

Extracellular proteins that were observed in both ex-vivo IgE-activated mouse bone marrow-derived mast cell and peritoneal-derived mast cell (PCMC) supernatants (top 20 protein PCMC proteins identified, according to mean shared protein spectral counts).

| Gene name | UniProt ID | Uniprot description | Normalized PCMC spectral counts (avg.) | Normalized BMCMC spectral counts (avg.) | Mean spectral counts of shared proteins |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALB | ALBU_BOVIN | Serum albumin | 190.95 | 209.58 | 200.27 |

| Anpep | AMPN_MOUSE | Aminopeptidase N | 213.66 | 170.67 | 192.17 |

| Man2b1 | MA2B1_MOUSE | Lysosomal alpha-mannosidase | 162.04 | 195.21 | 178.63 |

| Grn | Q544Y8_MOUSE | Granulin | 137.44 | 103.40 | 120.42 |

| Cpa3 | Q542E3_MOUSE | Carboxypeptidase A3, mast cell | 166.55 | 46.79 | 106.67 |

| Man2b2 | MA2B2_MOUSE | Epididymis-specific alpha-mannosidase | 142.38 | 48.62 | 95.50 |

| Hexb | Q3TXR9_MOUSE | Putative uncharacterized protein | 138.51 | 42.62 | 90.56 |

| Glb1 | Q3TAW7_MOUSE | Beta-galactosidase | 106.38 | 55.50 | 80.94 |

| Naglu | A2BFA6_MOUSE | Alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase | 105.93 | 38.96 | 72.44 |

| Cma1 | CMA1_MOUSE | Mast cell protease 5 | 113.96 | 30.30 | 72.13 |

| Pkm | KPYM_MOUSE | Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 | 45.40 | 87.59 | 66.50 |

| Tln1 | TLN1_MOUSE | Talin-1 | 80.15 | 51.73 | 65.94 |

| Tpsb2 | B5A5B2_MOUSE | Tryptase beta 2 | 106.77 | 24.32 | 65.54 |

| Pdcd6ip | PDC6I_MOUSE | Programmed cell death 6-interacting protein | 89.03 | 39.59 | 64.31 |

| Lcp1 | PLSL_MOUSE | Plastin-2 | 61.34 | 64.68 | 63.01 |

| Iqgap1 | IQGA1_MOUSE | Ras GTPase-activating-like protein IQGAP1 | 79.60 | 44.75 | 62.18 |

| Myh9 | MYH9_MOUSE | Myosin-9 | 41.59 | 81.99 | 61.79 |

| Aldoa | Q5FWB7_MOUSE | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 68.73 | 53.66 | 61.19 |

| Lgals3bp | LG3BP_MOUSE | Galectin-3-binding protein | 64.19 | 51.36 | 57.78 |

| Vwa5a | VMA5A_MOUSE | von Willebrand factor A domain-containing protein 5A | 87.43 | 26.63 | 57.03 |

Mast cells produce and release FXIIIA upon activation

Our proteomics study revealed that the transglutaminase FXIIIA was one of the most abundant proteins released by BMCMCs upon activation. Transglutaminases are multifunctional proteins (e.g., enzymatic and scaffolding functions) that are known to regulate cellular processes in homeostatic and disease states. 7 FXIIIA is one of 9 transglutaminases in humans, all of which (with the exception of band 4.2, which is catalytically inactive) share the same catalytic site sequence. FXIIIA becomes catalytically active once it dissociates from FXIIIB and a 37 AA peptide is cleaved from its N-terminus (the active form of FXIIIA is called FXIIIa). FXIIIA is best known for its involvement in fibrin cross-linking for clot stabilization, and it is the only transglutaminase known to be involved in the coagulation cascade.8 FXIIIA-deficiency can result in moderate to severe hemorrhagic diathesis. 9 Furthermore, FXIIIA can also contribute to processes in which mast cells play a key role, such as wound healing, cell migration and innate immunity.10 FXIIIA is present in the cytoplasm of platelets and monocytes/macrophages;11 however, FXIIIA expression has never been reported in mast cells.

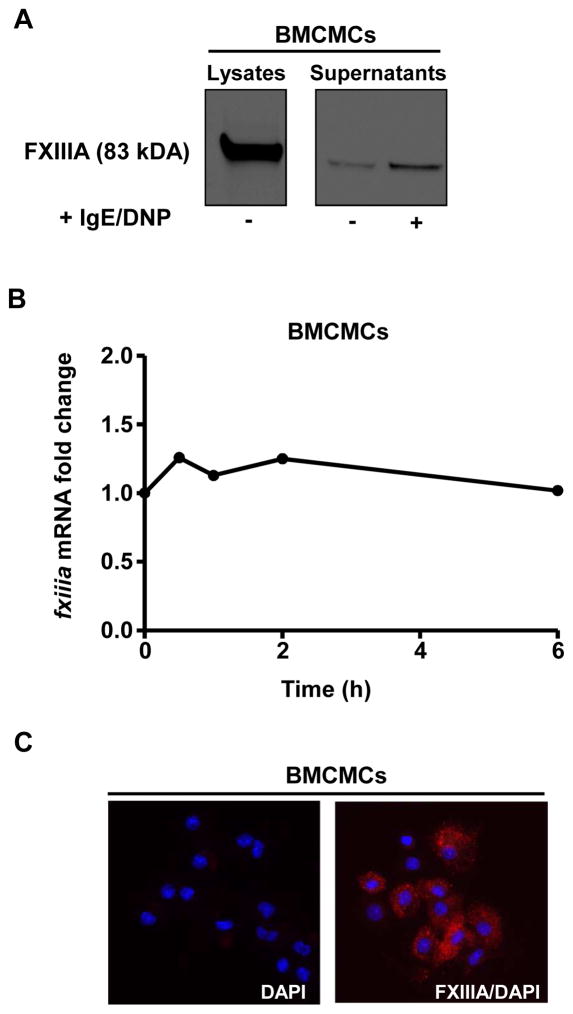

By using western blot analysis, we estimated that BMCMCs contained 800 fg FXIIIA per cell (Suppl. Fig. 1), which is around 10-fold greater than what is reported for platelets.12 There is evidence for FXIIIA entering the alternative secretory pathway; however, its secretion by an immune cell has not been demonstrated. 13 Our mass spectrometry data (Table 2) and western blot analysis (Fig. 2A) indicate that IgE/antigen-activated BMCMCs secrete FXIIIA upon activation.

Figure 2. Mast cells produce and release FXIIIA.

BMCMCs were sensitized with IgE mAb to DNP (2 μg/ml) overnight and then were challenged with DNP-HSA (100 ng/ml) for 6 h (A) or for the indicated time points (B). (A) FXIIIA (83 kDa) was observed by Western blot analysis in BMCMC protein lysate and their extracellular supernatant. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) FXIIIA expression was analyzed by qPCR. The FXIIIA versus GAPDH mRNA expression level for the BMCMCs that were incubated in media alone was assigned a value of 1.0 for calculation of the corresponding IgE/antigen stimulated BMCMC results. The data were pooled from the 3 independent experiments. (C) Immunofluorescence of fixed and permeabilized BMCMCs labeled first with anti-FXIIIA antibody and then with Alexa Fluor® 594-conjugated anti-mouse donkey polyclonal antibody (red). The cells were mounted with anti-fade reagent containing DAPI for nuclear staining (blue). The images are representative of 2 experiments.

In contrast to monocytes,14 BMCMCs did not display increased FXIIIA mRNA expression after activation (Fig. 2B) suggesting that FXIIIA protein is pre-formed in mast cells. Indeed, we observed that intracellular FXIIIA exhibited a typical granular pattern in BMCMCs (Fig. 2C), confirming that FXIIIA is stored in mast cell granules.

Mast cell deficiency leads to increased FXIIIA levels and reduced bleeding time

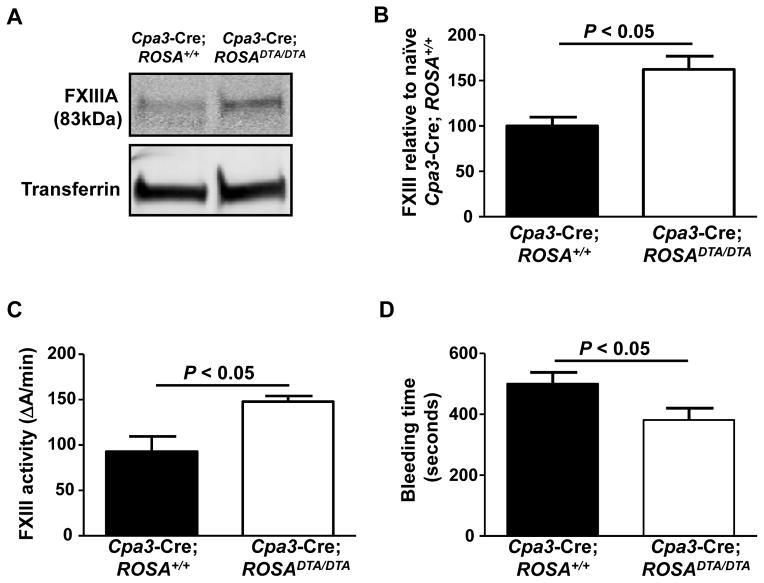

To investigate the relative contribution of mast cells to FXIIIA plasma levels in homeostatic conditions, we examined the Cpa3-Cre; ROSADTA/DTA mast cell- and basophil-deficient mice (a c-kit independent mast cell- and basophil-deficient strain).15 We found that Cpa3-Cre; ROSADTA/DTA mice exhibited increased FXIIIA plasma (Figs. 3A and 3B) and FXIIIa activity levels (Fig. 3C) indicating that mast cells and/or basophils significantly contribute to down-regulation of FXIIIA levels rather than to contribute to production of FXIIIA circulating pool in naïve mice. To determine whether basophils contribute to FXIIIA down-regulation we used Mcpt8DTR mice, which express DTR only in basophils and in which basophils can be selectively depleted after a single i.p. injection of DT.16 Plasma from basophil-depleted mice (Mcpt8DTR/+) exhibited similar plasma FXIIIA amounts as basophil competent mice (Mcpt8+/+) (Suppl. Fig. 2) indicating that mast cells, and not basophils, down-regulate FXIIIA under homeostatic conditions.

Figure 3. Cpa3-Cre; ROSA DTA/DTA mast cell- and basophil-deficient mice exhibit increased plasma FXIII amounts and activity, as well as reduced bleeding time.

(A) Western blot and (B) densitometry analyses for plasma FXIIIA levels in Cpa3-Cre; ROSA+/+ (n = 4) and Cpa3-Cre; ROSADTA/DTA mice (n = 7). (C–D) FXIIIa activity levels (C) and tail tip bleeding times (D) in Cpa3-Cre; ROSA+/+ (n = 11–13) and Cpa3-Cre; ROSADTA/DTA mice (n = 7–20).

To determine the physiological impact of the increased FXIIIA and FXIIIa activity levels due to mast cell deficiency, we assessed bleeding times in Cpa3-Cre; ROSADTA/DTA mice because bleeding time is a measurement that is directly linked to active FXIIIa levels.17 We observed that Cpa3-Cre; ROSADTA/DTA mice exhibited reduced bleeding times than their littermate controls (Fig. 3D) suggesting that mast cell-mediated down-regulation of FXIIIA amounts can influence clotting.

Overall, our findings indicate that despite the ability of mast cells to produce FXIIIA, mast cells mainly contribute to the down-regulation of FXIIIA levels and consequently reduce clotting during homeostatic conditions.

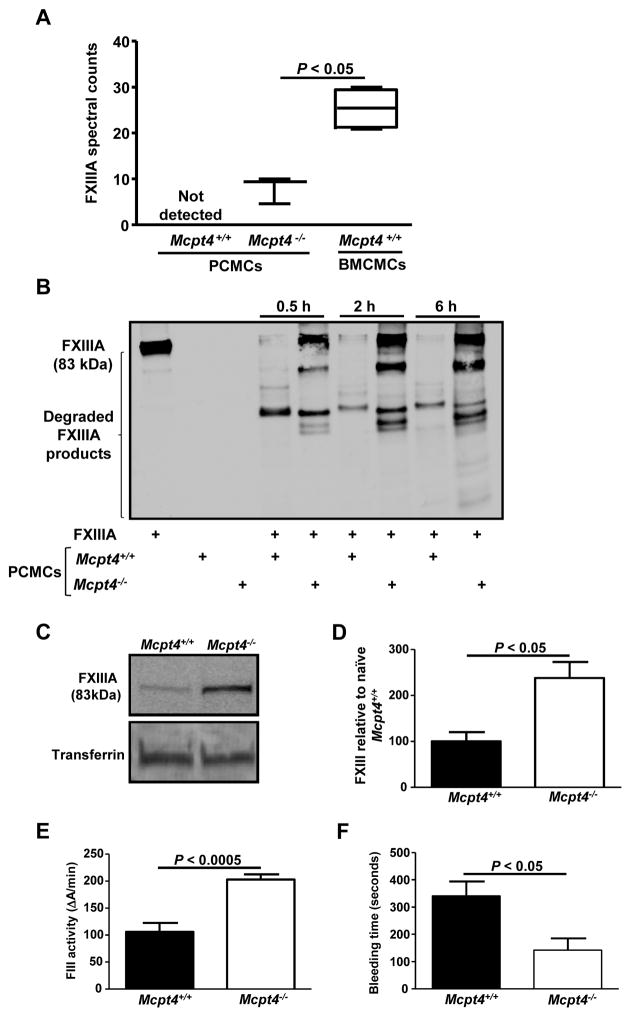

Mouse chymase down-regulates FXIIIA levels and function via proteolysis

PCMC lysates contain lower FXIIIA amounts than BMCMC lysates (240 fg FXIIIA per cell). Moreover, our mass spectrometry data revealed that PCMCs do not generate detectable amounts of FXIIIA in their supernatants upon activation in contrast to BMCMCs (Table 1, Fig. 4). This observation led us to hypothesize that PCMCs are more efficient in FXIIIA down-regulation than in its production. Therefore, we decided to investigate mechanisms by which PCMCs down-regulate FXIIIA levels. Prior studies using mouse recombinant mast cell proteases and non-specific protease inhibitors suggested that mast cell proteases are able to down-regulate certain cytokines and chemokines via proteolytic degradation.18–21 Our proteomics data showed that IgE/antigen-activated PCMCs generate releasates that are richer in their protease content than releasates generated by BMCMCs. In fact, mMCP-4, the mouse homologue of human chymase,22 was one of the most abundant proteins found in the PCMC releasate and one of the least abundant amongst the BMCMC releasate proteins (Tables 1 and 2, Suppl. Tables 1 and 2, and Suppl. Fig. 3). This finding is in agreement with previous reports by us and other groups that BMCMCs generated from mice in the C57BL/6 background express low mMCP-4 levels.4, 23, 24 As the FXIIIA amino acid sequence contains potential cleavage sites for chymase,3 we investigated whether mMCP-4 can down-regulate FXIIIA via proteolysis. To test this hypothesis, we used mMCP-4-deficient mice (Mcpt4−/− mice) which do not exhibit any marked defects in the concentrations of other mast cell proteases, including mMCP-5, -6 or carboxypeptidase A, in their peritoneal mast cells.22 Our mass spectrometry data indicated that Mcpt4+/+ PCMC releasates contained lower FXIIIA spectral count levels than the releasates generated by Mcpt4−/− PCMCs (Fig. 4A). Moreover, we found that the Mcpt4+/+ PCMC lysates caused more extensive FXIIIA degradation than the Mcpt4−/−PCMC lysates (Fig. 4B), indicating that chymase contributes to FXIIIA fragmentation. Analysis of IgE/DNP-HSA-activated PCMCs that were obtained from Mcpt4+/+ or Mcpt4−/− mice indicated that chymase does not substantially influence FXIIIA mRNA production (Suppl. Fig. 4), indicating that FXIIIA down-regulation by chymase mainly occurs at the post-transcriptional level.

Figure 4. Mouse chymase (mMCP-4) down-regulates FXIIIA plasma levels and activity via proteolytic degradation and contributes to prolonged bleeding times under homeostatic conditions.

(A) Wild type (Mctp4+/+) (n = 5) and mMCP-4-deficient (Mcpt4−/−) (n = 3) mouse PCMCs and Mcpt4+/+ BMCMCs (n = 6) were sensitized with IgE mAb to DNP (2 μg/ml) overnight and then were challenged with DNP-HSA (100 ng/ml) for 6h. The cell supernatants were collected, concentrated, and subjected to shotgun proteomics. The FXIIIA abundance is expressed in spectral counts. (B) PCMC lysates were incubated with human FXIIIA for the indicated time points at 37° C. The FXIIIA levels and their fragments were assessed with Western blot analysis. The data are representative of those obtained in 2 independent experiments. (C) Western blot analysis and (D) densitometry values for plasma FXIIIA levels in Mcpt4+/+ (n = 5) and Mcpt4−/− mice (n = 5). (E–F) FXIIIa activity levels (E) and tail tip bleeding times (F) in Mcpt4+/+ (n = 8–9) and Mcpt4−/− mice (n = 5–8).

Similarly to the mast cell- and basophil-deficient mouse, Mcpt4−/− mice exhibited increased FXIIIA plasma (Figs. 4C and 4D) and FXIIIa activity levels (Fig. 4E) indicating that chymase significantly contribute to down-regulate FXIIIA levels and function. Moreover, Mcpt4−/− mice exhibited reduced bleeding times than Mcpt4+/+ mice (Fig. 4F) suggesting that chymase-mediated down-regulation of FXIIIA amounts also influences clotting.

Therefore, our data suggest that FXIIIA may be a potential target for mMCP-4 proteolytic activity, and hence mast cells contribute to FXIIIA down-regulation.

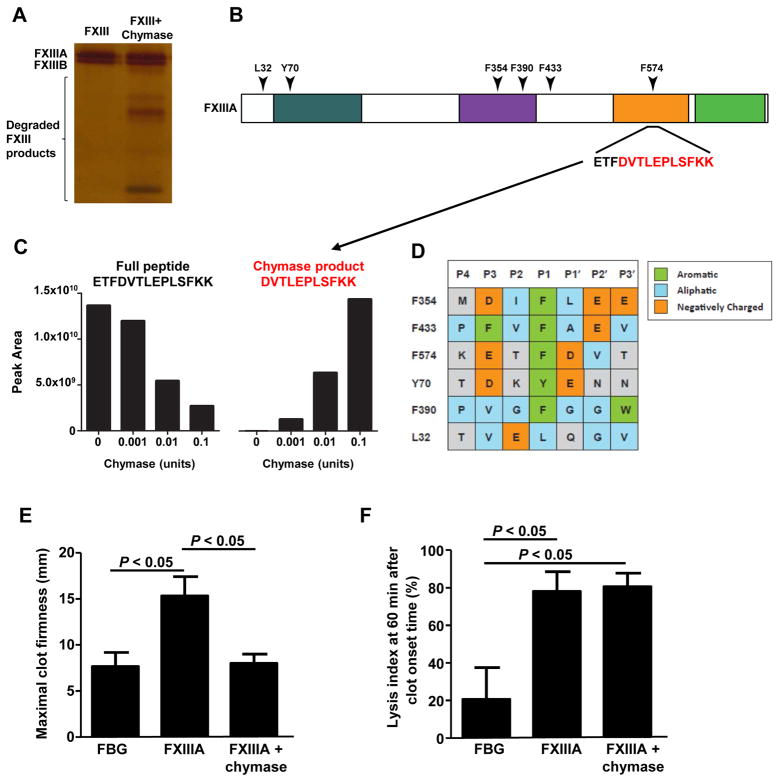

Human chymase degrades FXIIIA and diminishes its activity

mMCP-4 and human chymase share similar substrate specificity. 25 Therefore, we hypothesized that human chymase may also have the ability to down-regulate FXIIIA via proteolysis. FXIIIA that was incubated with human skin chymase led to extensive fragmentation of FXIIIA, but not FXIIIB (Fig. 5A and mass spectrometry data not shown). We performed in vitro cleavage reactions containing FXIIIA and increasing chymase concentrations to identify chymase cleavage sites. By focusing on the peptides identified in the FXIIIA samples that were incubated with the lowest utilized chymase concentration (0.001U), we identified peptides containing non-tryptic termini that represent 6 potential chymase cleavage sites (Fig. 5B). Using label-free quantitative mass spectrometry, we found that these putative chymase cleavage products increased in abundance with increasing chymase concentrations, as depicted for the cleavage site at F574 (Fig. 5C). Additionally, for 5 out of 6 of these high affinity cleavage sites, we found that chymase cleavage followed aromatic residues (P1) (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, the amino acids that were two residues upstream and downstream of the cleavage site (P3 and P2′) were enriched for aliphatic or negatively charged residues (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. Human chymase degrades FXIIIA and diminishes its activity.

(A) Human FXIIIA was incubated with human skin chymase for 6 h at 37 °C. FXIIIA fragmentation was assessed by silver stain analysis. The data are representative of those obtained from 3 independent experiments. (B) A human FXIIIA domain map, including the conserved transglutaminase regions and the location of the detected chymase cleavage sites are shown. (C) FXIIIA was incubated with increasing concentrations of human skin chymase for 6 hours at 37 °C and then subjected to LC-MS/MS. Six chymase cleavage sites in FXIIIA produced a marked dose-response to the increasing chymase levels, as exemplified for cleavage site F574. (D) An approximation of the consensus peptide sequence alignment patterns containing the detected chymase cleavage sites. Chymase cleavage occurs between P1 and P1′. The peptide sequences shown were sorted in order of their negatively charged and aliphatic residues. (E–F) ROTEM results are reported as maximal clot firmness (MCF) (E), which represents fibrin polymerization, FXIIIa activity, and the lysis index 60 (LI60) (F), which represents the percentage of the remaining clot in relation to the MCF value at 60 min after clot onset time. The data were pooled from 3 independent experiments.

These data are consistent with the reported substrate specificity for human chymase 25 and suggest that human chymase is sufficient to specifically cleave FXIIIA.

Interestingly, our mass spectrometric analysis of FXIIIA degradation showed that human chymase did not cleave FXIIIA at all of the potential cleavage sites. One of the possible explanations is that chymase accessibility to certain cleavage sites may be reduced by the presence of charged or bulky amino acids in P4-P2 or P3′-P4′. In fact, cleavage at F574 may not be favored by chymase over other sites according to substrate specificity; however, 3D structure analysis revealed that F574 is a very accessible site for chymase cleavage (data not shown). To confirm that the FXIIIA fragmentation data obtained with our mass spectrometry analysis were derived from chymase activity, we designed a peptide (GVP) spanning the chymase site, F574, which could compete with FXIIIA for chymase-mediated cleavage (Suppl. Fig. 5A). Our in vitro data indicated that GVP could prevent FXIIIA degradation by human chymase and Mcpt4+/+ PCMC lysates (Suppl. Figs. 5B and 5C) indicating that FXIIIA fragmentation was caused by chymase proteolytic activity.

To assess whether chymase-mediated FXIIIA degradation leads to the generation of peptides with reduced biological activity, we performed a ROTEM clot lysis assay with the FXIIIA digests. Chymase alone had no effect on fibrin clot formation by thromboelastography, indicating that chymase could not cleave and inactivate thrombin-activated FXIIIa when it was added simultaneously with FXIIIA and thrombin to this assay (data not shown). FXIIIA incubation with chymase prior to ROTEM impaired the ability for FXIIIA to strengthen the fibrin clot (Fig. 5E); however, it did not affect clot stability (Fig. 5F) demonstrating that FXIIIA cleavage by chymase leads to the generation of FXIIIA fragments with reduced biological activity.

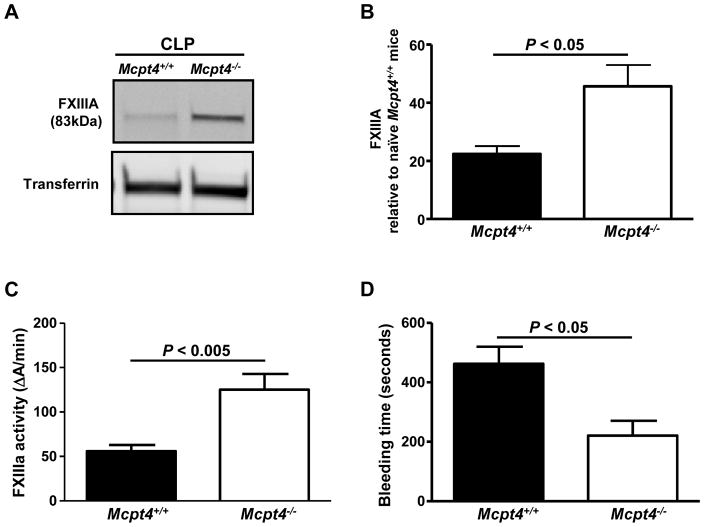

Chymase-deficient mice exhibit increased plasma FXIIIA levels and activity during experimental sepsis

Taking into account our in vitro data, we investigated whether chymase-FXIIIA interactions influence disease outcome. For this purpose, we investigated chymase-FXIIIA interactions in sepsis because fibrinolysis and its down-regulation is a key component of the septic coagulation response, and increased FXIIIa activity levels correlate with disease severity and fatality in sepsis.26 Mcpt4+/+ mice exhibited a significant reduction in FXIIIA plasma and activity levels when compared with naïve Mcpt4+/+ mice (Figs. 4C, 6A and 6B) at 24 h after experimental sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). This observation seemed to indicate that FXIIIA is consumed during sepsis as observed for other coagulation factors in this disorder.27 Mcpt4−/− mice exhibited reduced downregulation of FXIIIA plasma and activity levels when compared with naïve Mcpt4−/− mice or Mcpt4+/+ mice at 24 h after CLP (Figs. 4A, 6A and 6B) indicating that FXIIIA consumption during sepsis is partially mediated by chymase. On the contrary, Mcpt4+/+ and Mcpt4−/− mice exhibited similar plasma fibrinogen levels after CLP (Suppl. Fig. 6), suggesting that the chymase-mediated effects on FXIIIa activity levels were not an indirect result of changes in upstream mediators of the coagulation cascade.

Figure 6. mMCP-4 diminishes FXIIIA amounts and FXIII activity levels in mice during experimental sepsis.

(A) Western blot analysis and (B) densitometry values for FXIIIA plasma levels, (C) FXIIIa plasma activity levels, and (D) bleeding times at 24 h after CLP in Mcpt4+/+ (n = 5–9) and Mcpt4−/− mice (n = 3–8).

We also observed that the Mcpt4−/− mice did not have increased bleeding times, as were observed with the Mcpt4+/+ mice (Fig. 6D), suggesting that mMCP-4 mediated downregulation of FXIIIA plasma and activity levels at 24 h after CLP impaired their capacity to stop bleeding. Therefore, these data demonstrate that mMCP-4 not only degrades FXIIIA in vitro but it also reduces its function, which likely causes alterations in the clotting system during sepsis.

DISCUSSION

Accumulating in vitro and in vivo evidence indicates that mast cell functions may be much broader than their well-defined contribution to IgE-associated immune-responses. In this study, we characterized mast cell releasates in order to further understand the contribution of mast cells to health and disease. For this purpose, we used proteomics as an unbiased approach to characterize mast cell secretomes. Previous studies used mass spectrometry analysis to dissect signaling pathways that are involved in IgE-mediated mast cell activation; 28,29,30 however, a characterization of the mediators that are released by mast cells upon activation has not yet been reported. Therefore, we characterized the releasates generated by BMCMCs and PCMCs upon IgE/antigen-mediated activation. BMCMCs and PCMCs were utilized because these cells can be generated in the large numbers that are required for mass spectrometry analysis (25 million cells/treatment), and they are the closest in vitro “surrogates” to the two main murine mast cell subtypes, MMCs and CTMCs. Moreover, our BMCMC and PCMC culture conditions have been standardized and validated by us and other groups. However, we cannot dismiss the fact that the local microenvironment and the mechanisms of mast cell activation (IgE-dependent and IgE-independent) can influence the spectrum of mediators produced and released by mast cells from different locations during normal and pathological conditions. For example, we found that BMCMCs released reduced amounts of mast cell proteases upon IgE/antigen activation; however, MMCs can up-regulate certain proteases, such as the mast cell chymase, mMCP-1, during parasitic infections or following exposure to IL-9 or IL-10. 31 Therefore, further studies using alternative mass spectrometry methods that allow for low cell number usage will be important to replicate our work using freshly isolated cells from naïve and challenged mice. In the meanwhile, the validation of unexpected or unknown mast cell mediators that are found studying cultured mast cells may be possible by independent verification of their expression using databases such as the one provided by the Immunological Genome Project (ImmGen, http://www.immgen.org/databrowser/) when complemented with targeted proteomics. By using Immgen, we retrieved information that freshly isolated mast cells from the trachea, tongue, esophagus, skin, and peritoneum express FXIIIA mRNA, as we found for BMCMCs and PCMCs.

The mechanisms that regulate and/or shape the extracellular proteomes that are generated by different mast cell populations are unclear. We found that releasates from IgE/antigen-activated PCMCs were enriched in mediators that are associated with proteolysis as a main biological function (Table 1). In contrast, releasates from IgE/antigen-activated BMCMC contained a large number of mediators with immune regulatory capabilities and reduced proteolytic activity. From this observation, we hypothesized that proteolytic cleavage is a mechanism that can shape the profile of mediators produced by mast cells. For example, a mast cell type with a reduced number and/or diversity of proteases, such as BMCMCs, may be prone to regulate immune responses through the production of mediators, such as cytokines or chemokines, after IgE/antigen-mediated activation. Our proteomics findings were especially notable when we investigated how mast cells that express different protease profiles could differentially regulate the levels of the same mediator, FXIIIA, and affect its function during healthy and septic conditions. We focused our attention on FXIIIA due to its high abundance in the BMCMC releasates and undetectable levels in the PCMC releasates. Based on our proteomics findings pertaining to the protease profiles, we hypothesized that while BMCMCs contribute to FXIIIA production, PCMCs mainly contribute to FXIIIA degradation via proteolysis upon IgE-mediated activation.

The capability of mast cells to secrete FXIIIA suggests that these cells may contribute to plasma FXIIIA levels in addition to the FXIIIA that is potentially produced by platelets and other myeloid cells. 32 However, we found that mast cell-deficient mice exhibited increased total and active FXIIIA plasma levels (Figs. 3A, 3B and 3C). Moreover, mast cell deficient mice also exhibited reduced bleeding times (Fig. 3D). 17 Overall, these observations suggest that mast cells may significantly influence clotting processes through FXIIIA down-regulation. Our findings with mMCP-4 deficient mice (Fig. 4) suggest that chymase is involved in the down-regulation of FXIIIA amounts and function under homeostatic conditions.

It has been shown that murine 33 and rat chymase 34 can be constitutively secreted by naïve mast cells. Therefore, we think that constant or intermittent release of mast cell-derived chymase downregulates FXIIIA amounts and function. The mechanism by which mast cells release chymase in unchallenged rodents is unknown but it may involve piecemeal degranulation as observed for mast cells from the human intestine. 35

What is the relevance of FXIIIA-chymase interactions during disease? To answer this question, we utilized the CLP model of sepsis because diminished fibrinolysis is a key component of the septic coagulation response36 and because we observed that chymase plays a key role in protecting from sepsis by proteolytically cleaving inflammatory mediators that exacerbate the disease. 4 We found that chymase deficiency in mice subjected to CLP partially restored their plasma FXIIIA levels to those observed in naïve mice (Figs. 3B and 6B), suggesting that chymase released from activated mast cells may degrade FXIIIA during CLP. Notably, neutrophil elastase can also inactivate FXIIIA, 37 which makes our findings even more noteworthy considering that Mcpt4−/− mice exhibit an augmented hyperinflammatory response, which is mainly neutrophilic, during CLP.4 Septic Mcpt4−/− mice exhibited reduced bleeding times, likely as a consequence of their increased FXIIIa activity levels (Figs. 6C and 6D). However, we did not detect fibrin deposition in the kidneys of Mcpt4−/− mice, which is indicative of septic disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), a potential cause of acute kidney injury that Mcpt4−/− mice develop after CLP.4 This evidence suggests that the increased FXIIIa activity levels we observed in the chymase-deficient mice did not cause significant coagulopathy alterations. These observations are consistent with the fact that severe CLP-induced sepsis, as is the septic phenotype that Mcpt4−/− mice develop after CLP surgery, is a weaker inducer of DIC.38 FXIII-deficiency impairs myeloid cell migration39,40 and inflammation after myocardial infarction.41 Therefore, FXIIIA may be able to contribute to the hyper-inflammatory response that Mcpt4−/− mice develop after CLP,4 by inducing myeloid cell mobilization.

We can only speculate for now on when mast cell-mediated production of FXIIIA may influence disease outcomes or may overcome its degradation by chymase. For example, mast cell-derived FXIIIA may prevent pathogen dissemination that contributes to pathogen entrapment into clots, 42 or contribute to the coagulopathies that are observed with systemic mastocytosis. 43 However, we should point out that this assumption comes with the caveats that mast cells produce other mediators with the ability to influence coagulation, such as heparin and tryptase44 and there are additional cellular sources of FXIIIA.8 Moreover, mast cell activation in non-allergic disorders may involve certain IgE-independent stimuli to which CTMCs may be more responsive than MMCs, leading to a more pronounced reduction in FXIIIA levels and activity than that observed after IgE-dependent mast cell activation. Therefore, we believe that further studies will be necessary to assess the contribution of mast cell-derived FXIIIA to health and disease, ideally using mice with FXIIIA-deficiency in mast cell-specific subsets.

The relevance of our murine findings regarding the contribution of FXIIIA-mast cell interactions in human homeostasis and disease still requires investigation. We performed a pilot study in which we investigated FXIIIA expression in nasal polyp mast cells from chronic rhinosinusitis patients. We found that a subset of mast cells located in the epithelium submucosa and around the glands of nasal polyps expressed FXIIIA (Suppl. Fig. 7). Interestingly, FXIIIA expressing cells within glands are rare. These observations correlate with the chymase expression levels that were recently reported for mast cells in nasal polyps, in which chymase expression levels were low in mast cells that were located in the epithelium and high for mast cells located in the nasal polyp glands.45 These findings raise questions regarding the contribution of mast cells in nasal polyp development. In fact, our findings suggest that gland mast cells may have a beneficial effect by reducing excessive fibrin deposition in nasal polyps via chymase-mediated proteolytic degradation of FXIIIA that is produced by either mast cells themselves or by M2 macrophages.46

Conclusions

Overall, our studies in mice and humans suggest that mast cells have the ability to produce and degrade FXIIIA depending on their chymase expression profile: mast cells expressing chymase degrade FXIIIA, while mast cells that do not express chymase mainly produce FXIIIA. We believe that our findings exemplify a new level of complexity for mast cells in health and disease: the mast cell protease content can shape its extracellular mediator profile.

Supplementary Material

Clinical implications.

Unbiased characterization of mast cell releasates by mass spectrometry analysis has the potential to provide a better understanding of the contribution of mast cells to health and disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research for this work was supported by grants for A.M.P. from the National Institute of Health (NIH) (HL113351-01) and American Heart Association (12GRNT9680021), for R.G.J. from the NIH (5R00HL103768-04), and a fellowship for N.J.S. from the American Association of Immunologists (2015 AAI Careers in Immunology Fellowship). N.J.W. is supported, in part, by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (grant KL2 TR000421), a component of the NIH. S.R.R. was supported by the Parker B. Francis Fellowship. M.A. was supported by the Swedish Research Council. This work is supported in part by the University of Washington’s Proteomics Resource (UWPR95794).

We thank Dr. Piper Treuting for the critical advice regarding histological studies with chymase-deficient mice and Dr. Hajime Karasuyama for the Mcpt-8-DTR mice.

Abbreviations used

- BMCMCs

bone marrow derived-cultured mast cells

- PCMCs

peritoneal cell-derived mast cells

- FXIIIA

coagulation factor XIIIA

- mMCP

mouse mast cell protease

- CPA

carboxypeptidase A

- MMC

mucosal mast cells

- MCTC

connective tissue mast cells

- CLP

cecal ligation and puncture

- DNP-HSA

2, 4-Dinitrophenyl-Human Serum Albumin

- DIC

disseminated intravascular coagulation

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-mass spectrometry

- ROTEM

rotational thromboelastometry

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

Author contributions: N.J.S, V.A.G, M.C., P.T., N.J.W., G.H.D., S.R.R., and T.V. performed the experiments; V.A.G., N.J.W., M.A., G.P., N.J.W., G.H.D., S.R.R., T.V., and R.G.J. interpreted results and assisted with manuscript writing; N.J.S and A.M.P. wrote the manuscript; A.M.P. directed the project.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Galli SJ, Tsai M, Marichal T, Tchougounova E, Reber LL, Pejler G. Approaches for analyzing the roles of mast cells and their proteases in vivo. Adv Immunol. 2015;126:45–127. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pejler G, Ronnberg E, Waern I, Wernersson S. Mast cell proteases: multifaceted regulators of inflammatory disease. Blood. 2010;115:4981–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-257287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson MK, Karlson U, Hellman L. The extended cleavage specificity of the rodent beta-chymases rMCP-1 and mMCP-4 reveal major functional similarities to the human mast cell chymase. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:766–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.06.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piliponsky AM, Chen CC, Rios EJ, Treuting PM, Lahiri A, Abrink M, et al. The chymase mouse mast cell protease 4 degrades TNF, limits inflammation, and promotes survival in a model of sepsis. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:875–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Razin E, Ihle JN, Seldin D, Mencia-Huerta JM, Katz HR, LeBlanc PA, et al. Interleukin 3: A differentiation and growth factor for the mouse mast cell that contains chondroitin sulfate E proteoglycan. J Immunol. 1984;132:1479–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malbec O, Roget K, Schiffer C, Iannascoli B, Dumas AR, Arock M, et al. Peritoneal cell-derived mast cells: an in vitro model of mature serosal-type mouse mast cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:6465–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eckert RL, Kaartinen MT, Nurminskaya M, Belkin AM, Colak G, Johnson GV, et al. Transglutaminase regulation of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:383–417. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagoly Z, Katona E, Muszbek L. Factor XIII and inflammatory cells. Thromb Res. 2012;129(Suppl 2):S77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duckert F. Documentation of the plasma factor XIII deficiency in man. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1972;202:190–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1972.tb16331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douaiher J, Succar J, Lancerotto L, Gurish MF, Orgill DP, Hamilton MJ, et al. Development of mast cells and importance of their tryptase and chymase serine proteases in inflammation and wound healing. Adv Immunol. 2014;122:211–52. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800267-4.00006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muszbek L, Bereczky Z, Bagoly Z, Komaromi I, Katona E. Factor XIII: a coagulation factor with multiple plasmatic and cellular functions. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:931–72. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katona EE, Ajzner E, Toth K, Karpati L, Muszbek L. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the determination of blood coagulation factor XIII A-subunit in plasma and in cell lysates. J Immunol Methods. 2001;258:127–35. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00479-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordell PA, Kile BT, Standeven KF, Josefsson EC, Pease RJ, Grant PJ. Association of coagulation factor XIII-A with Golgi proteins within monocyte-macrophages: implications for subcellular trafficking and secretion. Blood. 2010;115:2674–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-231316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarvary A, Szucs S, Balogh I, Becsky A, Bardos H, Kavai M, et al. Possible role of factor XIII subunit A in Fcgamma and complement receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Cell Immunol. 2004;228:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lilla JN, Chen CC, Mukai K, BenBarak MJ, Franco CB, Kalesnikoff J, et al. Reduced mast cell and basophil numbers and function in Cpa3-Cre; Mcl-1fl/fl mice. Blood. 2011;118:6930–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wada T, Ishiwata K, Koseki H, Ishikura T, Ugajin T, Ohnuma N, et al. Selective ablation of basophils in mice reveals their nonredundant role in acquired immunity against ticks. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2867–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI42680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lauer P, Metzner HJ, Zettlmeissl G, Li M, Smith AG, Lathe R, et al. Targeted inactivation of the mouse locus encoding coagulation factor XIII-A: hemostatic abnormalities in mutant mice and characterization of the coagulation deficit. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88:967–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mallen-St Clair J, Pham CT, Villalta SA, Caughey GH, Wolters PJ. Mast cell dipeptidyl peptidase I mediates survival from sepsis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:628–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI19062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao W, Oskeritzian CA, Pozez AL, Schwartz LB. Cytokine production by skin-derived mast cells: endogenous proteases are responsible for degradation of cytokines. J Immunol. 2005;175:2635–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato A, Chustz RT, Ogasawara T, Kulka M, Saito H, Schleimer RP, et al. Dexamethasone and FK506 inhibit expression of distinct subsets of chemokines in human mast cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:7233–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy A, Ganesh G, Sippola H, Bolin S, Sawesi O, Dagalv A, et al. Mast cell chymase degrades the alarmins heat shock protein 70, biglycan, HMGB1, and interleukin-33 (IL-33) and limits danger-induced inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:237–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.435156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tchougounova E, Pejler G, Abrink M. The chymase, mouse mast cell protease 4, constitutes the major chymotrypsin-like activity in peritoneum and ear tissue. A role for mouse mast cell protease 4 in thrombin regulation and fibronectin turnover. J Exp Med. 2003;198:423–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens RL, Friend DS, McNeil HP, Schiller V, Ghildyal N, Austen KF. Strain-specific and tissue-specific expression of mouse mast cell secretory granule proteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:128–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ge Y, Jippo T, Lee YM, Adachi S, Kitamura Y. Independent influence of strain difference and mi transcription factor on the expression of mouse mast cell chymases. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:281–92. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63967-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersson MK, Enoksson M, Gallwitz M, Hellman L. The extended substrate specificity of the human mast cell chymase reveals a serine protease with well-defined substrate recognition profile. Int Immunol. 2009;21:95–104. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeerleder S, Schroeder V, Lammle B, Wuillemin WA, Hack CE, Kohler HP. Factor XIII in severe sepsis and septic shock. Thromb Res. 2007;119:311–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T, ten Cate H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:695–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamaoka K, Okayama Y, Kaminuma O, Katayama K, Mori A, Tatsumi H, et al. Proteomic Approach to FcepsilonRI aggregation-initiated signal transduction cascade in human mast cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009;149(Suppl 1):73–6. doi: 10.1159/000211376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Castro RO, Zhang J, Groves JR, Barbu EA, Siraganian RP. Once phosphorylated, tyrosines in carboxyl terminus of protein-tyrosine kinase Syk interact with signaling proteins, including TULA-2, a negative regulator of mast cell degranulation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:8194–204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.326850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bounab Y, Hesse AM, Iannascoli B, Grieco L, Coute Y, Niarakis A, et al. Proteomic analysis of the SH2 domain-containing leukocyte protein of 76 kDa (SLP76) interactome in resting and activated primary mast cells [corrected] Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:2874–89. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.025908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee YM, Jippo T, Kim DK, Katsu Y, Tsujino K, Morii E, et al. Alteration of protease expression phenotype of mouse peritoneal mast cells by changing the microenvironment as demonstrated by in situ hybridization histochemistry. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:931–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65634-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffin K, Simpson K, Beckers C, Brown J, Vacher J, Ouwehand W, et al. Use of a novel floxed mouse to characterise the cellular source of plasma coagulation FXIII-A. Lancet. 2015;385(Suppl 1):S39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scudamore CL, Pennington AM, Thornton E, McMillan L, Newlands GF, Miller HR. Basal secretion and anaphylactic release of rat mast cell protease-II (RMCP-II) from ex vivo perfused rat jejunum: translocation of RMCP-II into the gut lumen and its relation to mucosal histology. Gut. 1995;37:235–41. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wastling JM, Scudamore CL, Thornton EM, Newlands GF, Miller HR. Constitutive expression of mouse mast cell protease-1 in normal BALB/c mice and its up-regulation during intestinal nematode infection. Immunology. 1997;90:308–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dvorak AM, Furitsu T, Kissell-Rainville S, Ishizaka T. Ultrastructural identification of human mast cells resembling skin mast cells stimulated to develop in long-term human cord blood mononuclear cells cultured with 3T3 murine skin fibroblasts. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;51:557–69. doi: 10.1002/jlb.51.6.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schouten M, Wiersinga WJ, Levi M, van der Poll T. Inflammation, endothelium, and coagulation in sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:536–45. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bagoly Z, Fazakas F, Komaromi I, Haramura G, Toth E, Muszbek L. Cleavage of factor XIII by human neutrophil elastase results in a novel active truncated form of factor XIII A subunit. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:668–74. doi: 10.1160/TH07-09-0577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel KN, Soubra SH, Lam FW, Rodriguez MA, Rumbaut RE. Polymicrobial sepsis and endotoxemia promote microvascular thrombosis via distinct mechanisms. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1403–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dardik R, Krapp T, Rosenthal E, Loscalzo J, Inbal A. Effect of FXIII on monocyte and fibroblast function. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2007;19:113–20. doi: 10.1159/000099199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jayo A, Conde I, Lastres P, Jimenez-Yuste V, Gonzalez-Manchon C. Possible role for cellular FXIII in monocyte-derived dendritic cell motility. Eur J Cell Biol. 2009;88:423–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nahrendorf M, Hu K, Frantz S, Jaffer FA, Tung CH, Hiller KH, et al. Factor XIII deficiency causes cardiac rupture, impairs wound healing, and aggravates cardiac remodeling in mice with myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2006;113:1196–202. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.602094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loof TG, Morgelin M, Johansson L, Oehmcke S, Olin AI, Dickneite G, et al. Coagulation, an ancestral serine protease cascade, exerts a novel function in early immune defense. Blood. 2011;118:2589–98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stankovic K, Sarrot-Reynauld F, Puget M, Massot C, Ninet J, Lorcerie B, et al. Systemic mastocytosis: predictable factors of poor prognosis present at the onset of the disease. Eur J Intern Med. 2005;16:387–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prieto-Garcia A, Zheng D, Adachi R, Xing W, Lane WS, Chung K, et al. Mast cell restricted mouse and human tryptase. heparin complexes hinder thrombin-induced coagulation of plasma and the generation of fibrin by proteolytically destroying fibrinogen. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:7834–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.325712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takabayashi T, Kato A, Peters AT, Suh LA, Carter R, Norton J, et al. Glandular mast cells with distinct phenotype are highly elevated in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:410–20. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takabayashi T, Kato A, Peters AT, Hulse KE, Suh LA, Carter R, et al. Increased expression of factor XIII-A in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:584–92. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.