Abstract

The analysis of acylcarnitines (AC) in plasma/serum is established as a useful test for the biochemical diagnosis and the monitoring of treatment of organic acidurias and fatty acid oxidation defects. External quality assurance (EQA) for qualitative and quantitative AC is offered by ERNDIM and CDC in dried blood spots but not in plasma/serum samples. A pilot interlaboratory comparison between 14 European laboratories was performed over 3 years using serum/plasma samples from patients with an established diagnosis of an organic aciduria or fatty acid oxidation defect. Twenty-three different samples with a short clinical description were circulated. Participants were asked to specify the method used to analyze diagnostic AC, to give quantitative data for diagnostic AC with the corresponding reference values, possible diagnosis, and advice for further investigations.

Although the reference and pathological concentrations of AC varied among laboratories, elevated marker AC for propionic acidemia, isovaleric acidemia, medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, and multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiencies were correctly identified by all participants allowing the diagnosis of these diseases. Conversely, the increased concentrations of dicarboxylic AC were not always identified, and therefore the correct diagnosis was not reach by some participants, as exemplified in cases of malonic aciduria and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency. Misinterpretation occurred in those laboratories that used multiple-reaction monitoring acquisition mode, did not derivatize, or did not separate isomers. However, some of these laboratories suggested further analyses to clarify the diagnosis.

This pilot experience highlights the importance of an EQA scheme for AC in plasma.

Keywords: Acylcarnitines, External quality assurance, Fatty acid oxidation defects, Organic acidurias

Introduction

Acylcarnitines (AC) are esters formed by conjugation of acyl-CoAs and free carnitine by means of carnitine acyl transferases with different substrate specificities, either involved in the mitochondrial β-oxidation of fatty acids or in branched-chain amino acids catabolism. When acyl-CoAs accumulate in the mitochondrial matrix due to a specific metabolic disease, AC formation is favored, and then accumulation of AC in all physiological fluids reflects the mitochondrial acyl-CoA status. Consequently, the analysis of AC provides indirect evidence of mitochondrial metabolism (Bohles et al. 1994; Sewell and Bohles 1995).

The development of tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) facilitated the analysis of these compounds in the 1990s (Millington et al. 1990; Vreken et al. 1999). The recognition of disease-specific AC profiles in plasma and urine has proven very useful for the biochemical diagnosis and/or treatment monitoring of organic acidurias and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) defects, and therefore AC have become an important part of the investigation of inherited metabolic diseases in the biochemical genetic laboratories. Analysis of AC by MS/MS is also used in the expanded neonatal screening programs of many countries using dried blood spots (DBS) (McHugh et al. 2011).

More recently, there has been an increasing demand for satisfactory quality assurance in the biochemical genetic laboratories including external quality control to guarantee comparability of results between different centers (Fowler et al. 2008). Both institutions European Research Network for evaluation and improvement of screening, Diagnosis and treatment of Inborn Errors of Metabolism (ERNDIM, www.erndim.org) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, www.cdc.gov) offer excellent external quality assurance (EQA) schemes for qualitative and quantitative analysis of AC in DBS, respectively. The ERNDIM EQA scheme is probably more suitable for biochemical genetic laboratories, while the program of CDC is more useful for neonatal screening programs, where measurement of diagnostic AC is crucial for the identification of the diseases in asymptomatic neonates. However, AC are often determined in plasma or serum samples in biochemical genetic centers. Although quantitative analysis of a limited number of commercially available AC in serum has been introduced recently (ERNDIM Special Assays Serum scheme), so far no qualitative/interpretative EQA scheme exists for a comprehensive range of AC in plasma/serum samples. This study considers a pilot interlaboratory comparison between 14 European centers carried out between 2012 and 2014, by circulating plasma/serum samples from a range of well-defined FAO defects and organic acidurias in order to evaluate the analytical performance and interpretation of AC.

Samples and Methods

Samples

Twenty-three authentic serum or plasma samples from patients with one of the following eighteen different defects were used: five FAO defects [carnitine acylcarnitine translocase (CACT), long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD), multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MAD), medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD), very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD)], 12 organic acidurias [ethylmalonic encephalopathy (ETHE1), glutaric aciduria type I (GAI), holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency (HCS), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency (HMGL), isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (IBDH), isovaleric acidemia (IVA), β-ketothiolase deficiency (β-KT), malonic aciduria (MA), methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency (MCC), methylmalonic aciduria (MMA), combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria (MMA + Hcys), propionic acidemia (PA)], and one plasma sample from a patient affected with a combined defect of short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD) and IVA (SCAD + IVA). Diagnoses were confirmed biochemically, by enzyme testing and/or mutation analysis. Most cases were receiving l-carnitine supplementation at the time of sampling. Some defects were circulated twice to evaluate reproducibility of performance.

De-identified plasma samples, stored at −20°C over several years, were pooled together from samples remaining after analysis for diagnosis or treatment monitoring. Aliquots (60 μL), each with a short clinical description, were circulated twice a year at room temperature by regular mail from Madrid or Copenhagen to the different participants between 2012 and 2014. Samples were received by the participants within 2–7 days. Instructions were given that samples should be assayed within 5 days or should be frozen at −20°C until assay. Two aliquots from the samples (VLCAD/2013 and GAI/2014) were lost during transport and could not be analyzed by two laboratories.

Fourteen centers participated in this study: four laboratories studied all 23 samples from the beginning; then more laboratories progressively joined our program; thus, four laboratories analyzed 20 samples; one lab analyzed 11 samples; three analyzed seven samples and two additional laboratories only three samples.

AC Analytical Methods

Participants were asked to specify the method used, to give quantitative results for the AC relevant to the diagnosis with their corresponding reference values, the probable diagnosis and advice for further investigations. As in other qualitative/interpretative ERNDIM schemes, results were required to be returned within 3 weeks of receipt of the samples. On completion of each survey, a report was sent to participants to enable them to evaluate their own results.

All laboratories analyzed acylcarnitines by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS): 6/14 used custom-made or commercial mixes of deuterated AC (Chromsystems, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, or PerkinElmer) to quantify samples (one-point calibration), and only two of them included deuterated glutarylcarnitine (C5DC); 3/14 used external calibration with unlabeled AC and some deuterated AC as internal standards; one lab used a combined methodology, and the remainder did not inform about the standards or the quantification method used.

Eight of fourteen laboratories analyzed the AC as butylated derivatives, five of fourteen analyzed them underivatized, and one lab analyzed both forms, butylated and underivatized acylcarnitines. Table 1 shows the list of AC isomers and differences in their identification by both methods. Nine of the fourteen laboratories used full-scan precursor ion acquisition mode, and 5/14 laboratories used the multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) mode.

Table 1.

List of acylcarnitine (AC) isomers without or with derivatization involved in this scheme

| Underivatized | Derivatized | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m/z | Notation | AC | m/z | Notation | AC |

| 232 | C4 | Butyryl Isobutyryl |

288 | C4 | Butyryl Isobutyryl |

| 244 | C5:1 | Tiglyl 3-Methylcrotonyl |

300 | C5:1 | Tiglyl 3-Methylcrotonyl |

| 246 | C5:0 | Isovaleryl 2-Methylbutyryl-(d+l) Pivaloyl |

302 | C5:0 | Isovaleryl 2-Methylbutyryl-(d+l) Pivaloyl |

| 248 | C3DC C4OH |

Malonyl 3-Hydroxybutyryl |

360 | C3DC | Malonyl |

| 304 | C4OH | 3-Hydroxybutyryl | |||

| 262 | C4DC | Methylmalonyl-(d + l) Succinyl |

374 | C4DC | Methylmalonyl-(d+l) Succinyl |

| C5OH | 3-Hydroxyisovaleryl 2-Methyl-3-hydroxybutyryl |

318 | C5OH | 3-Hydroxyisovaleryl 2-Methyl-3-hydroxybutyryl |

|

| 276 | C5DC C6OH |

Glutaryl Hydroxyhexanoyl |

388 | C5DC C10OH |

Glutaryl Hydroxydecanoyl |

| 290 | C6DC | Methylglutaryl Adipyl |

402 | C6DC | Methylglutaryl Adipyl |

One lab included the separation of the short-chain isomers in its routine method, and two other laboratories only performed it when they considered necessary.

The presence of the marker AC was checked immediately before sending the samples to the participants and after 7 days by leaving the samples at room temperature, mimicking the transport conditions.

Results

The concentration variations of the AC in some problematic samples before sending and after 7 days at room temperature are presented in Table 2. Considerable differences in AC concentrations between the two measurements were observed in some samples, but in most cases the decreases in the AC concentrations did not prevent diagnosis. Two exceptions were the samples LCHAD/2012 and MMA + Hcys/2014. In these samples some of the diagnostically relevant AC were within the control range after 7 days at room temperature.

Table 2.

Marker acylcarnitines (AC) before sending the samples and after 7 days at room temperature in some problematic samples (data are from Madrid)

| Disease/year | Main marker AC | Day 0 (μmol/L) | Day 7 at room temperatures (μmol/L) | Upper reference level (μmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETHE1/2014 | C4 | 1.14 | 0.88 | 0.48 |

| C5 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.20 | |

| GAI/2012 | C5DC | 2.40 | 1.0 | 0.33 |

| GAI/2014 | C5DC | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.33 |

| HMGL/2012 | C5OH | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.05 |

| C6DC | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.04 | |

| HMGL/2014 | C5OH | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.05 |

| C6DC | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.04 | |

| LCHAD/2012 | C14OH | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| C16OH | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.03 | |

| C18:1OH | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.11 | |

| C18OH | 0.39 | 0.07 | 0.01 | |

| MA/2013 | C3DC | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.04 |

| MA/2014 | C3DC | 0.59 | 0.54 | 0.04 |

| MMA/2012 | C3 | 17.64 | 8.04 | 0.89 |

| C4DC | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.05 | |

| MMA+Hcys/2014 | C3 | 1.09 | 0.65 | 0.89 |

| C4DC | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

ETHE1 ethylmalonic encephalopathy, GAI glutaric aciduria type I, HMGL 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency, LCHAD long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, MA malonic aciduria, MMA methylmalonic aciduria, MMA+Hcys combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria

Analytical Performance

Reference values and pathological concentrations of AC measured varied considerably among laboratories. Figure 1 shows pathological and reference values for C5DC, marker for GAI, as an example of the variation between participants.

Fig. 1.

Pathological and reference values for C5DC in sample GAI/2012 in the different participant laboratories. URL upper reference level, RT room temperature

The increases of the following species, C3 (PA); C5:0 (IVA); C5:1 and C5OH (β-KT); C8:0, C10:1 and C10:0 (MCAD); C14:1 (VLCAD); C5-C18 (MADD); C16OH and C18:1OH (LCHAD); C16:0 and C18:1 (CACT); and C4:0 and C5:0 (ETHE1 or SCAD + IVA), were correctly identified by all laboratories (Table 3). Only two laboratories separated the isomers of C5:0, confirming the elevation of isovalerylcarnitine in the samples instead of the other two C5:0 species 2-methylbutyrylcarnitine or pivaloylcarnitine.

Table 3.

External quality assurance pilot study of acylcarnitines (AC) in serum/plasma

| Disease/year | Main marker AC | Concentrations of AC expressed as mean ± SD (range) (μmol/L) | Correct identification of the main marker AC/total number of participants | Correct interpretation of the diagnosis/total number of participants | Diagnosis missed by labs using derivatized AC | Diagnosis missed by labs using underivatized AC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA/2013 | C3 | 39 ± 16 (24–67) | 8/8 | 8/8 | None | None |

| IVA/2012 | C5:0 | 14.4 ± 1.1 (13.4–16) | 4/4 | 4/4 | None | None |

| β-KT/2013 | C5:1 | 0.66 ± 0.24 (0.46–1.15) | 7/8: C5:1 and C5OH | 8/8 | None | None |

| C5OH | 0.35 ± 0.15 (0.14–0.53) | 1/8: C5:1 | ||||

| β-KT/2014 | C5:1 | 0.75 ± 0.74 (0.47–1.29) | 12/12 | 12/12 | None | None |

| C5OH | 0.39 ± 0.24 (0.23–1.13) | |||||

| MCAD/2012 | C8:0 | 5.3 ± 2.4 (3.3–8.6) | 4/4 | 4/4 | None | None |

| C10:1 | 1.75 ± 0.71 (1.3–2.8) | |||||

| VLCAD/2013 | C14:1 | 0.82 ± 0.32 (0.52–1.49) | 7/7 | 7/7 | None | None |

| MAD/2013 | C5:0 | 1.45 ± 0.46 (0.7–2.1) | 8/8 | 8/8 | None | None |

| C8:0 | 1.69 ± 0.51 (1.02–2.04) | |||||

| C10:0 | 2.8 ± 1.4 (1.3–4.9) | |||||

| LCHAD/2012 | C16OH | 0.27 ± 0.12 (0.07–0.45) | 10/10 | 8/10: LCHAD/MTP | None | None |

| C18:1OH | 0.21 ± 0.16 (0.01–0.56) | 2/10: LCHAD | ||||

| CACT/2013 | C16:0 | 2.6 ± 0.5 (1.9–3.3) | 8/8 | 6/8: CPTII/CACT | None | None |

| C18:1 | 2.5 ± 0.4 (2.1–3.2) | 2/8: CPTII | ||||

| ETHE1/2014 | C4:0 | 1.5 ± 0.5 (0.98–2.8) | 12/12 | 11/12 | 1a/9a | 1a/5a |

| C5:0 | 0.54 ± 0.15 (0.38–0.75) | |||||

| SCAD + IVA/2014 | C4:0 | 6.8 ± 3.2 (4.2–12.5) | 8/9: C4:0 and C5:0 | 4/9: SCAD and IVA | 3/5 | 2/4 |

| C5:0 | 12.5 ± 3.5 (7.8–17.5) | 1/9: C5:0 | ||||

| IBDH/2014 | isoC4 or C4 | 0.77 ± 0.26 (0.47–1.3) | 6/9: C4 (only 2 as isoC4) | 4/9: IBDH | 3/5 | 2/4 |

| HCS/2014 | C3 | 1.2 ± 0.6 (0.83–2.1) | 5/9: C3 + C5OH | 3/9: HCS | 5/5 | 1/4 |

| C5OH | 0.39 ± 0.35 (0.25–1.17) | 3/9: C5OH or C3 | ||||

| MCC/2014 | C5OH | 5.5 ± 2.3 (1.2–7.8) | 7/9: C5OH + C5:1 | 7/9: MCC | 1/5 | 1/4 |

| C5:1 | 0.05; 0.031 | 2/9: C5OH/C4DC | ||||

| MA/2013 | C3DC | 0.85 ± 0.88 (0.02–1.32) | 4/8 | 5/8 | 1/5 | 2/3 |

| 1/8: C3DC/C4OH | ||||||

| MA/2014 | C3DC | 1.00 ± 1.04 (0.53–1.51) | 9/12 | 10/12 | 0/9a | 2/5a |

| 1/12: C3DC/C4OH | ||||||

| MMA/2012 | C3 | 17.9 ± 3.3 (12.8–23.6) | 8/10: C3 + C4DC | 8/10 | 2/7 | 0/3 |

| C4DC | 1.5 ± 2.1 (0.12–6.81) | 2/10: C5OH/C4DC | ||||

| MMA/2014 | C3 | 13.1 ± 2.9 (8–15.4) | 10/12: C3 + C4DC | 12/12 | None | None |

| C4DC | 0.73 ± 0.48 (0.12–1.77) | 2/12: C5OH/C4DC | ||||

| MMA+Hcys/2014 | C3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 (0.78–1.6) | 7/12: C3 + C4DC | 7/12 | 3a/9a | 3a/5a |

| C4DC | 0.33 ± 0.21 (0.11–0.62) | 5/12: C3 or C4DC | ||||

| GAI/2012 | C5DC | 0.93 ± 0.93 (0.11–2.4) | 9/10 | 10/10 | None | None |

| GAI/2014 | C5DC | 0.41 ± 0.66 (0.11–0.77) | 10/11 | 10/11 | 0/8a | 1/5a |

| HMGL/2012 | C5OH | 0.25 ± 0.19 (0.11–0.53) | 3/4: C5OH + C6DC | 3/4 | 0/2 | 1/2 |

| C6DC | 0.88 ± 0.84 (0.15–1.8) | 1/4: C5OH | ||||

| HMGL/2014 | C5OH | 0.34 ± 0.09 (0.25–0.62) | 9/12: C5OH + C6DC | 9/12 | 0/9a | 3/5a |

| C6DC | 0.29 ± 0.26 (0.8–0.92) | 3/12: C5OH |

CACT carnitine acylcarnitine translocase deficiency, CPTII carnitine palmitoyl-CoA transferase type II deficiency, ETHE1 ethylmalonic encephalopathy, GAI glutaric aciduria type I, HCS holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency, HMGL 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency, IBDH isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, IVA isovaleric acidemia, β-KT β-ketothiolase deficiency, LCHAD long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, MA malonic aciduria, MAD multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, MCAD medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, MCC methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency, MMA methylmalonic aciduria, MMA+Hcys combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, MTP mitochondrial trifunctional protein deficiency, PA propionic acidemia, SCAD+IVA combined defect of short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase and IVA, VLCAD very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency

aOne lab used combined methodology (butylated and underivatized AC)

Considering the quantitative results, it is interesting to note that the pathological levels of C5:0, C16 + C18:1, and those of C3 between 10 and 20 μmol/L (in MMA cases) were very similar in most laboratories. However, when C3 was lower than 5 μmol/L (as in the HCS case) or higher than 20 μmol/L (as in the PA case), the pathological levels varied from 0.83 to 2.1 μmol/L and from 24 to 67 μmol/L, respectively. These differences seem unrelated to the quantification methods used or to the derivatization of AC. The use of the same commercial mix of deuterated AC did not assure similar values.

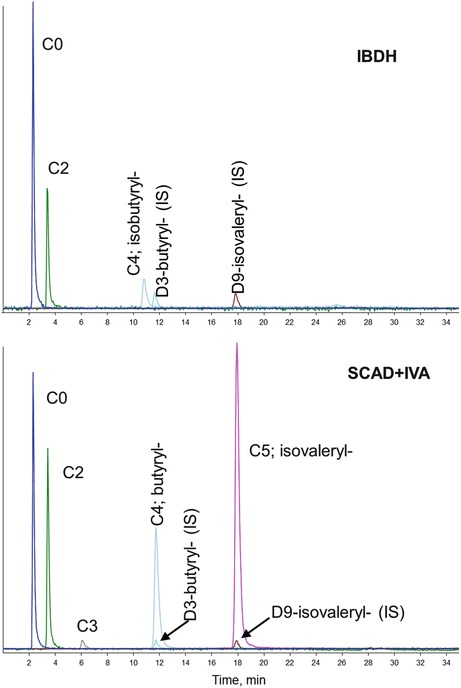

On the other hand the isolated increase of C4 in the IBDH sample was not consistently identified, and only two laboratories identified isobutyrylcarnitine (isoC4) by separation of isomers (Fig. 2). Another difficult sample was that of HCS where the slightly elevated levels of C3 and C5OH were not detected by some laboratories.

Fig. 2.

Separation of isomers in IBDH deficiency and a combined defect of SCAD and IVA by HPLC/MS/MS as described by Ferrer et al. (2007). IS internal standard. Chromatograms from lab in Madrid

The analytical performance of the dicarboxylic acylcarnitines (C3DC, C4DC, C5DC, and C6DC) was clearly unsatisfactory. One MA sample was circulated twice since some participants failed to correctly identify C3DC in the first round. In the second survey, we observed that two laboratories repeated the failure, because either C3DC was still not included in MRM acquisition or because C3DC and C4OH were isobaric in the underivatized method; consequently, relatively high reference values were in place (see Table 1).

Similarly one laboratory, which failed to identify C6DC in the first round because the MRM acquisition did not contain the transition for C6DC, did not modify the acquisition parameters between circulations. This resulted in a repeat failure with the second circulation of this sample.

Difficulty in the recognition of the abnormal profile (increases of C3 and C4DC) in three MMA samples (two mutase defects and one combined MMA and Hcys) was also observed. Only one laboratory routinely separates isomers of C4DC (d- and l-methylmalonyl carnitines and succinylcarnitine). The other two laboratories that were able to separate them did not use it in these samples. In the case of MMA + Hcys, both marker AC were only marginally elevated after 1 week at room temperature (Table 2), which could explain both the great dispersion in the quantitative results and the interpretation of this sample. In the other two MMA samples, the increases of C3 and C4DC were easily recognized by 8/10 and 10/12 laboratories, whereas 4/22 analyzing underivatized AC were unable to distinguish between C5OH and C4DC (Table 3).

The increase of C5DC in two GAI samples from low-excretor patients was detected by 86% of the participants. A wide range of reference and pathological C5DC levels was observed (Fig. 1) that seemed not to be related either to methodological aspects of the analysis, the use of deuterated C5DC as internal standard, or the inclusion of the derivatization step. C5DC was still not included in the list of AC acquired by MRM in one lab in the second round (sample GAI/2014), leading to a wrong diagnosis.

Interpretation

The diagnosis of PA, IVA, β-KT, MCAD, VLCAD, and MADD was reached by all participants (Table 3). Despite correct identification by all laboratories of [C16OH and C18:1OH] and [C16 and C18:1], markers for LCHAD/MTP defects and CPTII/CACT defects, respectively, some laboratories suggested only one of the two possible defects as possible diagnosis. Despite problems with the identification of C5DC, diagnosis of GAI was suggested by one participant based on the clinical information. Although most of the participants identified the marker AC of MMA (C3 and C4DC), two laboratories overlooked the increase of C4DC, and interpretation was correct in 20/22 cases.

Diagnostic proficiency was poor in cases of MA, HMGL, IBDH, combined SCAD + IVA defect, and a mild form of HCS. In the case of MA, a slight improvement in performance was observed in the second circulation. The interpretation was correct in 62.5% and 83% in the first and second round, respectively. In the case of HMGL, no improvement in performance was observed in samples that were circulated twice, with the same diagnostic proficiency of 75% in both rounds. In these two diseases, two laboratories either did not include C3DC and C6DC in the list of AC acquired by MRM or did not review their reference values between the two circulations, making it difficult to reach a correct interpretation. In the case of IBDH, the increase of C4 was identified by six out of nine laboratories, but only four of them suggested the diagnosis of IBDH/SCAD, while the remaining two only suggested an SCAD defect. In the case of a combined defect SCAD + IVA, despite the correct identification of raised C4 and C5 AC by all but one laboratory (which overlooked the increase of C4), the correct diagnosis was only achieved by 4/9, the remaining suggested IVA or MADD. Due to the rarity of this combined defect and being unable to separate isomers, some laboratories suggested an SCAD defect combined with pivaloyl carnitine derived from treatment. In the HCS sample, the diagnostic significance of the slightly elevated levels of C3 and C5OH was not recognized by most laboratories resulting in an incorrect diagnosis.

Misinterpretation occurred mainly in those laboratories with analytical issues, namely, those that did not derivatize (due to isobaric AC species rather than sensitivity), did not separate isomers, failed to include some MRM pairs in the MRM acquisition list, or did not consider the concentrations of diagnostically significant AC to be raised against their reference values. However, some laboratories with good analytical performance failed in the interpretation, possibly because of inexperience with these rarer conditions, and they overlooked pointers in the clinical data, e.g., the combined defect of SCAD + IVA or the mild form of HCS. Generally laboratories correctly suggested further analyses such as organic acid analysis in urine to confirm a diagnosis.

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrates that the identification of the monocarboxylic AC is not a major problem in most laboratories despite the interlaboratory variation in quantitative results and reference values. Conversely, the identification of the dicarboxylic AC presented some difficulties, both in analytical performance and interpretation. In this pilot scheme, some causes of poor analytical performance have been identified; however, other pitfalls and problems in these methodologies have been reported previously and should also be considered, e.g., appropriate conditions of butylation, half-life of the butyl esters, or the hydrolysis of acylcarnitines to free carnitine (Johnson 1999). Therefore, it is essential to be aware of all the relevant AC markers, and where MRM acquisition mode is used, the specific transitions of these AC should be included in the experiment. Laboratories should also be aware that the number of isobaric AC of interest is greater without derivatization than with derivatization. Those laboratories that include a derivatization step should be careful with the reaction conditions and the elapsed time until the MS/MS analysis. For a comprehensive analysis, isomer separation by HPLC/MS/MS is necessary in cases where the specific isomer present defines the diagnosis but not always if the overall AC profile is sufficient to infer the biochemical diagnosis. Finally, single-point calibration methods are faster and less laborious, but accuracy and/or precision can be sacrificed where the concentration analyte is considerably different to that of the internal standard used for quantitation.

In order to improve the analytical performance of AC analysis, some commercially available AC (C8, C5DC, C16, C18) have been included in the ERNDIM quantitative Special Assays in Serum (SAS) scheme starting in 2014, but it is still too early to evaluate the results. Further AC (C3 and C5) are planned to be added to the 2016 SAS distributions.

The interpretation of the pathological profiles of the common disorders (PA, IVA, β-KT, MCAD, MADD, and VLCAD) is, in general, well performed by most laboratories. However, some defects that are more prevalent in the Mediterranean area (like HMGL) or in North Europe (like the mild variant of HCS) are less well identified. This fact emphasizes the need of circulation of samples from such rare disorders as they offer a unique training resource in order to not overlook some diagnostic AC and miss the diagnosis (Bonham 2014).

Recently, a harmonized scoring system has been adopted by the ERNDIM Scientific Advisory Board for all interpretative schemes (two points for analytical performance and two points for interpretative proficiency). Since 2014 the concept of critical error has been introduced for the performance assessment for analytical or interpretative errors that would be unacceptable for most laboratories and would have serious adverse effects on patient management. If we had applied this concept here, those laboratories that misdiagnosed HCS, HMGL, or MA would be classified as poor performers.

Although the number of participants in this pilot experience was limited (only 14 laboratories), the feasibility of this scheme has been demonstrated during 3 years regarding sample suitability, stability, and robustness of result presentation and reporting. This work highlights the necessity of an analytical and interpretative ERNDIM EQA scheme for AC in plasma samples, being that ERNDIM supports the development of new EQA schemes as part of its activity (Fowler et al. 2008).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. A Sánchez for technical assistance in preparing the samples. We are grateful to the Scientific Advisory Board of ERNDIM for support and helpful discussions.

Sentence Take-Home Message

The need of external quality assurance programs for analysis of acylcarnitines in plasma is ascertained.

Details of the Contributions of Individual Authors

Conception and design: PRS, JO, BM

Analysis and interpretation of data: PRS, BM

Drafting the article or revising critically: PRS, GR, CA, JGV, LF, GL, WO, PP, AR, CVS, BM

Agreement to submission: all authors

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

P Ruiz Sala, G Ruijter, C Acquaviva, A Chabli, MGM de Sain-van der Velden, J Garcia-Villoria, MR Heiner-Fokkema, E Jeannesson-Thivisol, K Leckstrom, L Franzson, G Lynes, J Olesen, W Onkenhout, P Petrou, A Drousiotou, A Ribes, C Vianey-Saban, and B Merinero declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Ethical approval for the use of residual anonymized patient samples in this study was granted from the institutional Ethics Committee of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

Details of Funding

The authors confirm independence from the sponsors; the content of the article has not been influenced by the sponsors.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

Contributor Information

B. Merinero, Email: bmerinero@cbm.csic.es

Collaborators: Matthias R. Baumgartner, Marc Patterson, Shamima Rahman, Verena Peters, Eva Morava, and Johannes Zschocke

References

- Bohles H, Evangeliou A, Bervoets K, Eckert I, Sewell A. Carnitine esters in metabolic disease. Eur J Pediatr. 1994;153:S57–S61. doi: 10.1007/BF02138779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonham JR. The organisation of training for laboratory scientists in inherited metabolic disease, newborn screening and paediatric clinical chemistry. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:763–764. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I, Ruiz-Sala P, Vicente Y, Merinero B, Perez-Cerda C, Ugarte M. Separation and identification of plasma short-chain acylcarnitine isomers by HPLC/MS/MS for the differential diagnosis of fatty acid oxidation defects and organic acidemias. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;860:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler B, Burlina A, Kozich V, Vianey-Saban C. Quality of analytical performance in inherited metabolic disorders: the role of ERNDIM. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:680–689. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-1025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW. Inaccurate measurement of free carnitine by the electrospray tandem mass spectrometry screening method for blood spots. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1999;22:201–202. doi: 10.1023/A:1005443212817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh D, Cameron CA, Abdenur JE, Abdulrahman M, Adair O, Al Nuaimi SA, Ahlman H, Allen JJ, Antonozzi I, Archer S, Au S, Auray-Blais C, Baker M, Bamforth F, Beckmann K, Pino GB, Berberich SL, Binard R, Boemer F, Bonham J, Breen NN, Bryant SC, Caggana M, Caldwell SG, Camilot M, Campbell C, Carducci C, Bryant SC, Caggana M, Caldwell SG, Camilot M, Campbell C, Carducci C, Cariappa R, Carlisle C, Caruso U, Cassanello M, Castilla AM, Ramos DE, Chakraborty P, Chandrasekar R, Ramos AC, Cheillan D, Chien YH, Childs TA, Chrastina P, Sica YC, de Juan JA, Colandre ME, Espinoza VC, Corso G, Currier R, Cyr D, Czuczy N, D’Apolito O, Davis T, de Sain-Van der Velden MG, Delgado Pecellin C, Di Gangi IM, Di Stefano CM, Dotsikas Y, Downing M, Downs SM, Dy B, Dymerski M, Rueda I, Elvers B, Eaton R, Eckerd BM, El Mougy F, Eroh S, Espada M, Evans C, Fawbush S, Fijolek KF, Fisher L, Franzson L, Frazier DM, Garcia LR, Bermejo MS, Gavrilov D, Gerace R, Giordano G, Irazabal YG, Greed LC, Grier R, Grycki E, Gu X, Gulamali-Majid F, Hagar AF, Han L, Hannon WH, Haslip C, Hassan FA, He M, Hietala A, Himstedt L, Hoffman GL, Hoffman W, Hoggatt P, et al. Clinical validation of cutoff target ranges in newborn screening of metabolic disorders by tandem mass spectrometry: a worldwide collaborative project. Genet Med. 2011;13:230–254. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31820d5e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millington DS, Kodo N, Norwood DL, Roe CR. Tandem mass spectrometry: a new method for acylcarnitine profiling with potential for neonatal screening for inborn errors of metabolism. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1990;13:321–324. doi: 10.1007/BF01799385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewell AC, Bohles HJ. Acylcarnitines in intermediary metabolism. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:871–877. doi: 10.1007/BF01957495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreken P, van Lint AE, Bootsma AH, Overmars H, Wanders RJ, van Gennip AH. Quantitative plasma acylcarnitine analysis using electrospray tandem mass spectrometry for the diagnosis of organic acidaemias and fatty acid oxidation defects. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1999;22:302–306. doi: 10.1023/A:1005587617745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]