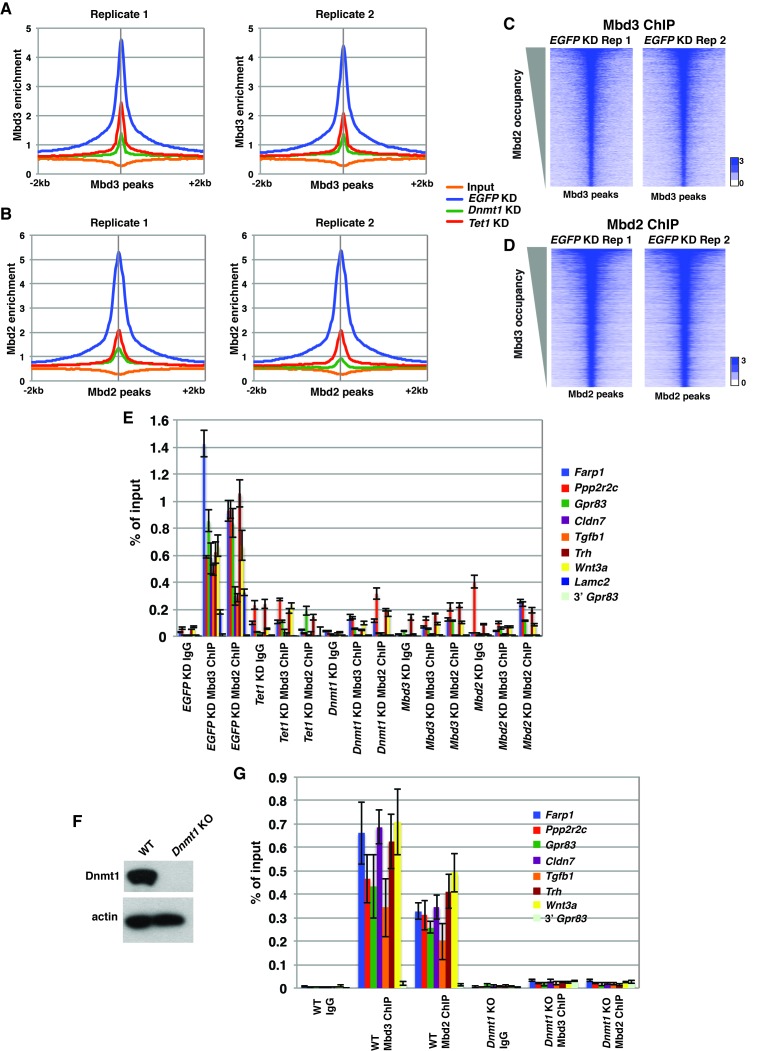

Figure 2. Dnmt1 and Tet1 are required for Mbd3 and Mbd2 binding in ES cells.

(A) Genome browser tracks of replicate ChIP-seq experiments examining endogenous Mbd3 or Mbd2 occupancy in control (EGFP KD), Dnmt1 KD, and Tet1 KD ES cells over indicated loci (Hoxd cluster). (B) Overlap of Mbd3 and Mbd2 binding. Shown are Venn diagrams delineating the overlap between all genomic locations (top panel) or TSS-proximal locations (−1 kb to +100 bp; bottom panel) bound by Mbd3 and Mbd2. (C–D) Aggregation plots of Mbd3 (C) or Mbd2 (D) ChIP-seq data showing occupancy over ICPs (top left panel, from [Weber et al., 2007]), annotated TSSs (bottom left panel), the LMR subset (top middle panel, from [Stadler et al., 2011]), gene-distal DHSs (bottom middle panel, from GSM1014154 with TSSs removed) Mbd2 peaks (top right panel, called from EGFP KD ChIP-seq experiments), and Mbd3 peaks (bottom right panel, called from EGFP KD ChIP-seq experiments) ± 2 kb in control (EGFP KD), Dnmt1 KD, or Tet1 KD ES cells. (E–F) Heatmaps of Mbd3 enrichment over Mbd3 binding sites sorted by Mbd2 occupancy (E) and Mbd2 enrichment over Mbd2 binding sites sorted by Mbd3 occupancy (F) in control (EGFP KD), Dnmt1 KD, or Tet1 KD ES cells. The profiles shown in aggregation plots and heatmaps represent the average of two biological replicates.