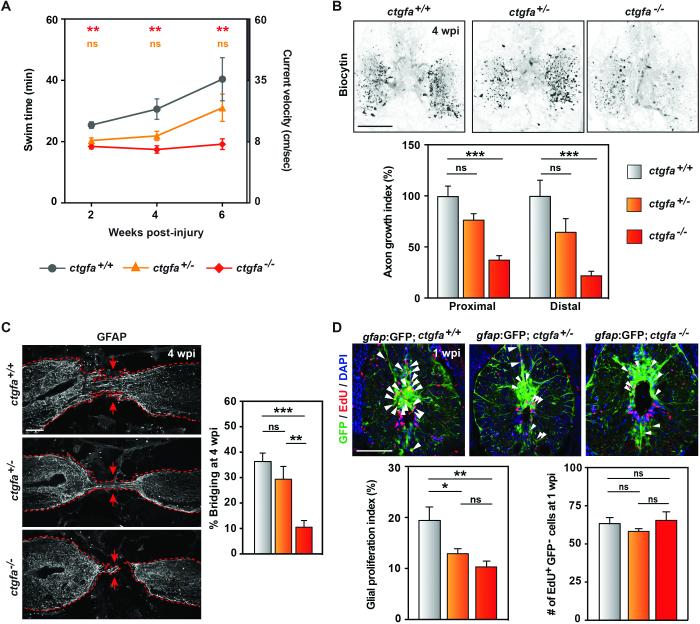

Fig. 2. ctgfa is necessary for glial bridging and spinal cord regeneration.

(A) Swim assays assessed animals’ capacity to swim against increasing water current inside an enclosed swim tunnel. Seven wild-type (ctgfa+/+), 10 ctgfa heterozygous (ctgfa+/−) and 10 mutant (ctgfa−/−) clutchmates were assayed at 2, 4, and 6 wpi. Statistical analyses of swim times are shown for ctgfa−/− (red) and ctgfa+/− (orange) compared to wild-types. Recovery of ctgfa−/− animals was not significant between 2 and 6 wpi. (B) Anterograde axon tracing in ctgfa mutant animals at 4 wpi. For quantification of axon growth at areas proximal (shown in images) and distal to the lesion core, 16 wild-type, 17 ctgfa+/−, and 20 ctgfa−/− zebrafish from 2 independent experiments were used. (C) GFAP immunohistochemistry in ctgfa mutant spinal cords at 4 wpi. Percent bridging was quantified for 10 wild-type, 9 ctgfa+/− and 10 ctgfa−/− clutchmates from 3 independent experiments. Dashed lines delineate glial GFAP staining, and arrows point to sites of bridging. (D) Glial cell proliferation in wild-type, ctgfa+/−, and ctgfa−/− spinal cords at 1 wpi. For quantification of glial proliferation indices (left) and number of EdU-positive gfap:GFP-negative cells (right), 10 wild-type, 12 ctgfa+/−, and 15 ctgfa−/− animals from 2 independent experiments were used. For statistical analyses, (*), (**) and (***) represent P-values of <0.05, <0.01, and <0.001, respectively; while (ns) indicates P-values > 0.05. Scale bars, 100 μm.