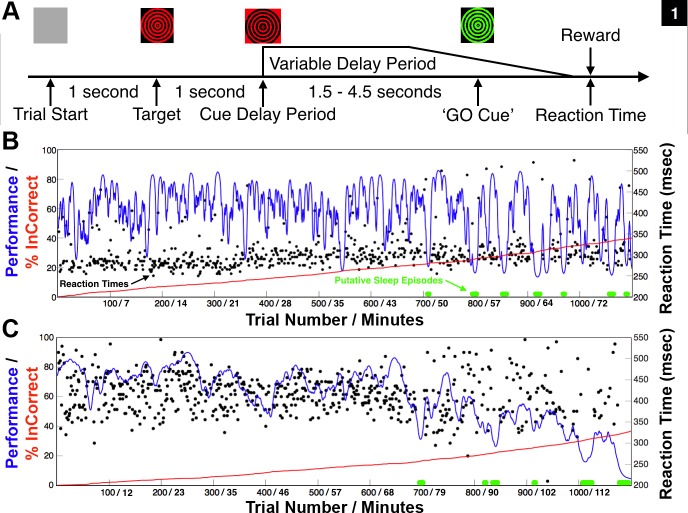

Fig. 1.

The animal's typical behavioral performance of the vigilance task during experimental sessions without central thalamic deep brain stimulation. When motivated to work for juice rewards, both animals typically performed until satiated and then ceased to work. A: structure of the vigilance task. To perform correctly, the animal had to maintain stable fixation (2 degree visual angle) on the displayed target (red/black dartboard) that would undergo contrast reversal, at 10 Hz, during stable fixation. The contrast reversal indicated the start of the variable delay period that would last 1.5–4.5 s and ended when the color of the target switched from red/black to green/black, “GO” cue, instructing the animal to touch an infrared switch for juice reward. B: native behavioral performance of nonhuman primate 1 (NHP1) during the vigilance task. The performance estimate is shown as a smoothly varying blue line (Smith et al. 2009), and reaction times of correctly performed trials are plotted in black. The red line indicates the cumulative number of incorrect trials. Periods of slow rolling eye movements, eye closure, and a presumed increase in drowsiness co-occurred with marked increases in the power of low-frequency oscillatory activity (4–8 Hz) recorded in frontal and midline ECoG electrodes (see methods) and are marked in green along the zero performance line. Mean delay period was 2.2 s and average performance in this session was 60% correct (660 of 1,100 trials). Trial number and total time on task are indicated. C: same as in B but for NHP2. Mean delay period was 4.2 s and average performance during this session was 61% correct (673/1,100 trials). Note the trending decrease in average performance and increased variance in reaction times following trial 600 in both animals, corresponding to ∼43 and 68 min time on task, respectively. Periods of eye closure and presumed increased drowsiness occurred frequently in the latter half of most experimental sessions. These trends are consistent with performance changes observed in additional animals performing the identical vigilance task (Shah et al. 2009; Smith et al. 2009) and in humans performing similar tasks continuously over extend periods of time (Paus et al. 1997).