Abstract

Spinal lamina I projection neurons serve as a major conduit by which noxious stimuli detected in the periphery are transmitted to nociceptive circuits in the brain, including the parabrachial nucleus (PB) and the periaqueductal gray (PAG). While neonatal spino-PB neurons are more than twice as likely to exhibit spontaneous activity compared to spino-PAG neurons, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear since nothing is known about the voltage-independent (i.e. ‘leak’) ion channels expressed by these distinct populations during early life. To begin identifying these key leak conductances, the present study investigated the role of classical inward-rectifying K+ (Kir2) channels in the regulation of intrinsic excitability in neonatal rat spino-PB and spino-PAG neurons. The data demonstrate that a reduction in Kir2-mediated conductance by external BaCl2 significantly enhanced intrinsic membrane excitability in both groups. Similar results were observed in spino-PB neurons following Kir2 channel block with the selective antagonist ML133. In addition, voltage-clamp experiments showed that spino-PB and spino-PAG neurons express similar amounts of Kir2 current during the early postnatal period, suggesting that the differences in the prevalence of spontaneous activity between the two populations are not explained by differential expression of Kir2 channels. Overall, the results indicate that Kir2-mediated conductance tonically dampens the firing of multiple subpopulations of lamina I projection neurons during early life. Therefore, Kir2 channels are positioned to tightly shape the output of the immature spinal nociceptive circuit and thus regulate the ascending flow of nociceptive information to the developing brain, which has important functional implications for pediatric pain.

Keywords: Superficial dorsal horn, projection neuron, leak conductance, intrinsic excitability

Lamina I of the spinal superficial dorsal horn (SDH) contains projection neurons that serve as a major conduit through which noxious stimuli detected in the periphery are transmitted to higher, pain-related brain regions (Mantyh et al., 1997; Nichols et al., 1999; Bester et al., 2000; Andrew, 2009). These projection neurons are innervated by peripheral nociceptive afferents and project their axons to multiple supraspinal circuits involved in pain processing (Hylden et al., 1989; Lima et al., 1991; Al-Khater and Todd, 2009; Todd, 2010). Approximately 80% of rat lamina I projection neurons target the parabrachial nucleus (PB), which modulates the emotional valence of pain perception via connections to the amygdala; while 20% of lamina I projection neurons target the periaqueductal gray (PAG), which mediates descending inhibition by endogenous enkephalin signaling and rostroventral medulla activation (Jhamandas et al., 1996; Price, 2000; Gauriau and Bernard, 2002; Vogt, 2005; Heinricher et al., 2009; Todd, 2010).

Lamina I projection neurons exhibit spontaneous activity throughout early postnatal development (Li and Baccei, 2012), which may provide an endogenous source of excitation to promote the activity-dependent tuning of supraspinal nociceptive circuits. However, the prevalence of spontaneous activity in neonatal projection neurons depends on their target in the brain, as the fraction of spino-PB neurons exhibiting spontaneous firing was 2–3 fold higher compared to spino-PAG neurons (Li and Baccei, 2011, 2012), which is consistent with prior reports showing that intrinsic membrane properties vary significantly across distinct neuronal populations within the spinal dorsal horn (Murase and Randic, 1983; Grudt and Perl, 2002; Prescott and De Koninck, 2002; Ruscheweyh et al., 2004). The mechanisms underlying the observed difference in the prevalence of spontaneous activity between immature spino-PB and spino-PAG neurons remain poorly understood, as nothing is known about the specific ionic conductances expressed by lamina I projection neurons during early life. Insight into the factors shaping the ascending flow of nociceptive information from the neonatal spinal cord to the brain is essential to obtaining a complete understanding of the neurobiological basis for pediatric pain.

Mounting evidence supports the critical importance of voltage-independent (i.e. ‘leak’) ion channels, such as classical inward-rectifying potassium (Kir2) channels, in regulating the intrinsic excitability of neurons in the CNS (Wilson and Kawaguchi, 1996; Marder and Goaillard, 2006; Young et al., 2009; Li et al., 2013). Kir2 channels are expressed in the neonatal rat spinal cord (Murata et al., 2016), where they have been shown to tightly regulate pacemaker activity within lamina I interneurons during early life (Li et al., 2013). Therefore, Kir2 channels are strong candidates to regulate membrane excitability within ascending projection neurons in the immature superficial dorsal horn. However, the role of Kir2-mediated conductance in modulating the firing of neonatal lamina I interneurons cannot necessarily be extrapolated to projection neurons, since ion channel expression can occur in a highly cell type-dependent manner in the spinal dorsal horn (Engelman et al., 1999; Yasaka et al., 2010; Hu and Gereau, 2011). Therefore, it remains unknown whether Kir2 channels are functionally expressed in neonatal lamina I projection neurons, and to what extent they contribute to shaping the output of immature spinal pain circuits.

The results below demonstrate that constitutive Kir2 channel activity dampens the intrinsic excitability of both spino-PB and spino-PAG neurons during early life, suggesting that these leak channels have a generalized role in restricting the ascending flow of nociceptive information to the developing brain and thereby limiting pain sensitivity. However, the similar expression of Kir2-mediated conductance in the two populations suggests that other ionic mechanisms must underlie the greater occurrence of spontaneous firing within immature spino-PB neurons.

Experimental Procedures

Ethical Approval

All experiments were conducted under strict adherence to the animal welfare guidelines set forth by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Back-labeling of lamina I projection neurons

Sprague-Dawley rats of both sexes were placed under a surgical plane of anesthesia with a mixture of ketamine (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) on postnatal day 1 (P1) and placed into a custom mold mounted in a stereotaxic frame (World Precision Instruments, Inc. Sarasota, FL). Under sterile conditions, lambda and portions of the parietal and occipital bones were exposed by surgical incision. A small hole was made with a drill (OmniDrill-35; World Precision Instruments, Inc. Sarasota, FL) using a ball mill carbide #1/4 burr (World Precision Instruments, Inc. Sarasota, FL, USA) above the right parabrachial nucleus (PB) or right periaqueductal gray (PAG), at stereotaxic coordinates (in mm, with respect to lambda); PB: −2.7 rostrocaudal (RC), −1.0 mediolateral (ML), −4.3 dorsoventral (DV); PAG: −1.9 RC, −0.6 ML, −2.9 DV. A Hamilton microsyringe (62RN; 2.5 µL), fitted with a 28-gauge needle, was loaded with FAST DiI oil (2.5 mg/ml). Using a microsyringe injector (Micro-4; World Precision Instruments, Inc. Sarasota, FL), the loaded Hamilton syringe was positioned at either the PB or PAG, and 120 nl DiI was injected at a rate of 25 nl/min (Figure 1A). Upon completion of the injection, the syringe was kept in place for 1 minute to allow for maximum DiI delivery. After withdrawal of the syringe, the surgical wound was closed using Vetbond™ (3M, St. Paul, MN USA). Animals undergoing surgery were kept on an electric heat pad maintained at 37°C, and were under observation until complete recovery from anesthesia, after which they were returned to their home cage for 2–4 days prior to electrophysiological experiments.

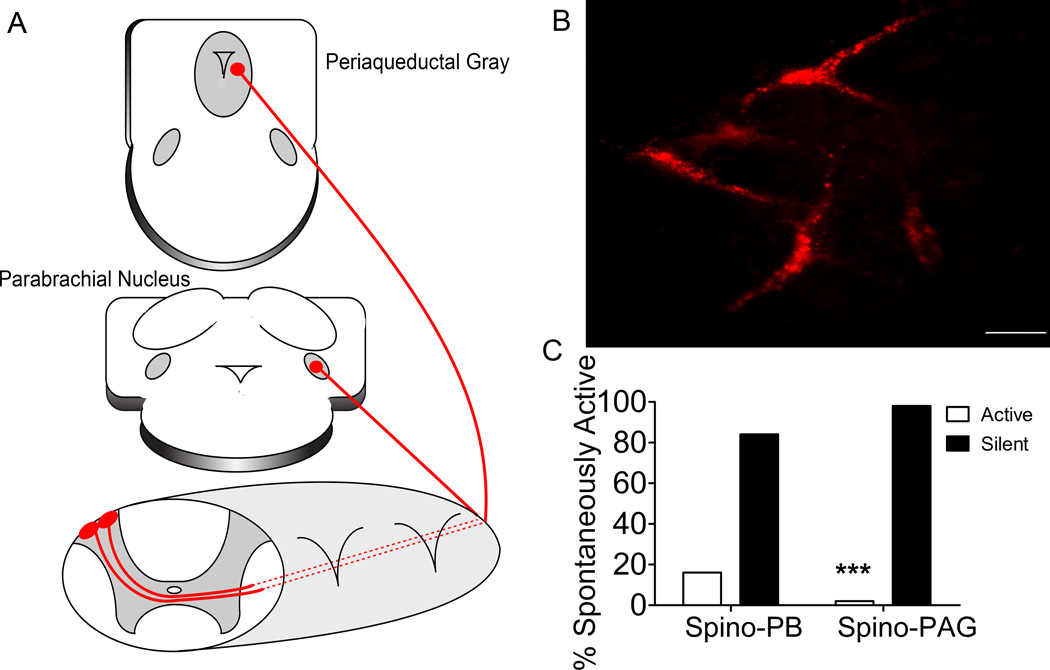

Figure 1. Neonatal rat spino-PB neurons are more likely to be spontaneously active compared to spino-PAG neurons.

A, Schematic representation of the DiI back-labeling strategy; DiI injection into the periaqueductal gray or the parabrachial nucleus resulted in effective labeling of lamina I projection neurons. B, Representative micrograph of DiI back-labeled spino-PB projection neurons in an intact spinal cord preparation; scale bar, 25 µM. C, Spino-PB projection neurons exhibit a significantly higher prevalence of spontaneous activity compared to spino-PAG neurons (n = 51, 11 rats, p = 0.0008, Fischer’s exact test).

Preparation of intact spinal cord

Tissue preparation was performed as previously described (Li et al., 2015). Briefly, DiI injected Sprague-Dawley rats, on P3–P5, were put under a deep plane of anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg; Fatal-Plus, Vortec Pharmaceuticals, Dearborn, MI). Animals were then transcardially perfused with ~10 mL of dissection solution composed of (in mM): 250 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, 6 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 25 glucose (pH = 7.2) then decapitated. Spinal cords were dissected from the vertebral column in oxygenated dissection solution, and then stripped of all meningeal layers. Finally, the lumbar enlargement was isolated and placed into a submersion-type recording chamber (RC-22; Warner Instruments, Hamden CT), then mounted onto the stage of an upright microscope (BX51WI; Olympus, Center Valley, PA), and perfused with room temperature, oxygenated aCSF composed of (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, 25 glucose, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2 at a rate of 1–3 ml/min.

Patch clamp recordings

Patch electrodes were constructed from thin-walled, single-filament borosilicate glass (1.5 mm outer diameter; World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL) using a microelectrode puller (P-97; Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Pipette tip resistances ranged from 4–6 MΩ, and seal resistances were > 1 GΩ. Patch electrodes were filled with a solution composed of (in mM): 130 K-gluconate, 10 KCl, 10 HEPES, 10 Na-phosphocreatine, 4 MgATP, 0.3 Na2GTP (pH 7.2, 305 mOsm).

Lamina I neurons were visualized in the intact spinal cord preparation using oblique infrared LED illumination as previously described (Safronov et al., 2007; Szűucs et al., 2009). DiI-labeled lamina I projection neurons were visualized by fluorescence illumination. Patch clamp recordings were obtained through the use of a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For recording under voltage clamp conditions, after establishment of the whole cell configuration, series resistance was evaluated and monitored to ensure that it remained < 20 MΩ. Fast synaptic transmission was blocked via bath perfusion (at 1–3 ml / min) of a solution containing (in µM): 10 NBQX, 25 AP-5, 10 gabazine, 0.5 strychnine (Tocris Bioscience; Bristol, UK). In some experiments BaCl2 was added to the bath solution at 0.2 mM. To isolate Kir2 currents, negative voltage ramps were applied via the patch electrode from −55 mV to −155 mV (0.2 mV / ms; 5 sweeps). Ramp currents were averaged and the Ba2+-sensitive component was obtained by electronic subtraction. Conductance was measured at two potentials equidistant from the reversal potential (i.e. ERev + 25 mV and ERev − 25 mV) as described previously (Derjean et al., 2003; Li et al., 2013). For recording under current clamp conditions, approximately 1 minute after whole-cell configuration establishment, spontaneous activity was recorded at the resting membrane potential (RMP). Membrane capacitance was determined by using the built-in pClamp membrane test. Input resistance (Rinput) was measured by applying a hyperpolarizing current step (−10 pA) via the patch electrode. Rheobase was measured by applying short depolarizing current steps (5 pA steps, 80 ms duration) until an action potential was generated. Action potential duration was measured by determining the elapsed time from the threshold to the half maximal amplitude during the repolarization phase of the action potential. Firing frequency was measured by applying sustained depolarizing current steps (10 pA steps, 800 ms duration). Instantaneous firing frequency measurements were obtained for each step by determining the mean interspike interval−1.

Data analysis and statistics

The data presented here were obtained from a total of 125 identified lamina I projection neurons that projected either to the parabrachial nucleus or the periaqueductal gray. These neurons were recorded in 24 rat pups ranging in age from P3–P5. All data sets passed Kolmogorov-Smirnoff normality tests, and were presented as mean ± SEM. Firing frequency measurements were compared using two-way repeated measures ANOVA, utilizing the Holm-Sidak method to make multiple comparisons. Observations of spontaneous activity prevalence were compared using Fischer’s exact test. All other measurements were compared using unpaired or paired t-tests. For all statistical tests, a resultant p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Neonatal spino-parabrachial neurons exhibit a higher prevalence of spontaneous activity compared to spino-periaqueductal gray neurons

Prior work conducted in spinal cord slices has demonstrated that spino-parabrachial (PB) neurons exhibit a 2–3 fold higher prevalence of spontaneous activity compared to spino-periaqueductal gray (PAG) neurons (Li and Baccei, 2012). However, it remained unclear if this difference in spontaneous firing is also observed in the intact spinal cord preparation, which better preserves the morphology, dendritic arborizations, and axon trajectories of lamina I neurons (Safronov et al., 2007; Szűcs et al., 2009). Patch clamp recordings from back-labeled projection neurons in the intact spinal cord (Figure 1A, B) confirmed that spino-PB projection neurons exhibit a significantly higher prevalence of spontaneous activity compared to spino-PAG neurons (Figure 1C, n = 52, 11 rats, p = 0.0008, Fischer’s exact test), although the occurrence of spontaneous firing was less common than previously noted in spinal cord slices (Li and Baccei, 2011, 2012) for both groups of projection neurons.

Spino-PB and spino-PAG neurons express similar levels of Kir2 current during the neonatal period

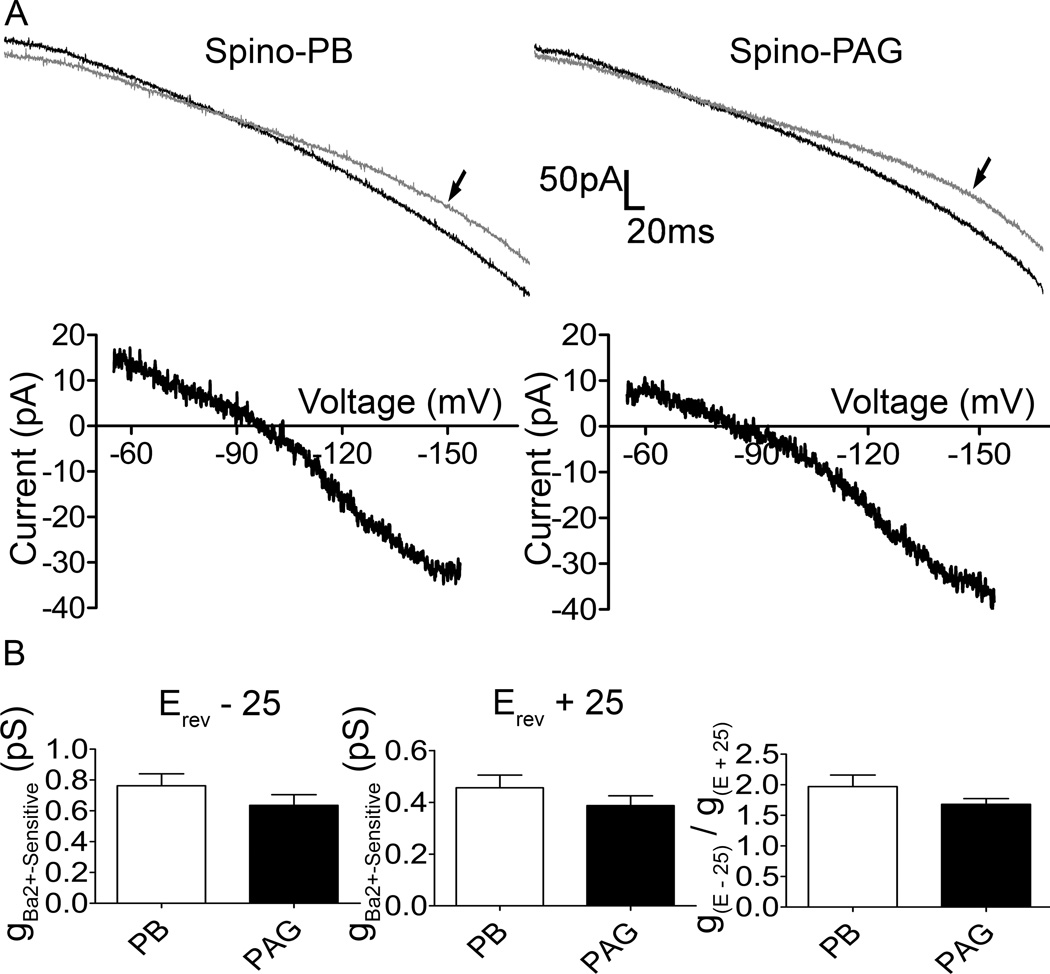

Classical Kir2 channels have been shown to be constitutively active at resting membrane potentials, sensitive to externally applied Ba2+, and exhibit strong inward rectification (Standen and Stanfield, 1978; Day et al., 2005; Li et al., 2013). To characterize Kir2 currents in immature lamina I projection neurons, whole-cell patch clamp recordings were obtained from identified spino-PB or spino-PAG neurons in an intact spinal cord prepared at postnatal day (P)3–P5. Currents were evoked by the application of a negative voltage ramp before and after the bath application of BaCl2 (Figure 2A), which is selective for Kir channels at concentrations less than 1 mM (Coetzee et al., 1999). In both populations of projection neurons, the currents evoked by the voltage ramp were sensitive to 200 µM Ba2+ (Figure 2A, top panels). Isolation of the Ba2+-sensitive component via electronic subtraction (Figure 2A, lower panels) revealed an inward rectifying current with a mean reversal potential (Spino-PB, Erev = −98.2 ± 2.6 mV; Spino-PAG, Erev = −96.6 ± 1.7 mV) close to the predicted equilibrium potential of K+ under our experimental conditions. These characteristics are consistent with the well-documented biophysical properties of Kir2 channels (Liu et al., 2001; Young et al., 2009; Sepulveda et al., 2015). Importantly, there was no significant difference in the level of Ba2+-sensitive conductance between neonatal spino-PB and spino-PAG neurons (Fig. 2B, left, Erev − 25, p = 0.23, unpaired t-test; Fig. 2B, middle, Erev + 25, p = 0.27, unpaired t-test) or in the degree of inward rectification (Fig. 2B, right, p = 0.17, unpaired t-test).

Figure 2. Spino-PB and spino-PAG projection neurons express Kir2-mediated current during early life.

A top, Representative whole-cell current traces evoked by a 100 mV (−55 mV to −155 mV) hyperpolarizing voltage ramp applied to spino-PB (left) and spino-PAG (right) projection neurons. Gray trace with arrow indicates recorded current in the presence of Ba2+; black trace, recorded current in the absence of Ba2+. A bottom, Representative Ba2+-sensitive components following electronic subtraction. B, comparisons of measured Ba2+-sensitive conductance (Erev − 25, left; Erev + 25, middle) and inward rectification ratio (gE − 25 / gE + 25, right) between spino-PB and spino-PAG projection neurons revealed no significant differences between groups. n = 31, 12 rats, for all comparisons.

Kir2 channels tonically reduce the intrinsic excitability of multiple populations of lamina I projection neurons during early life

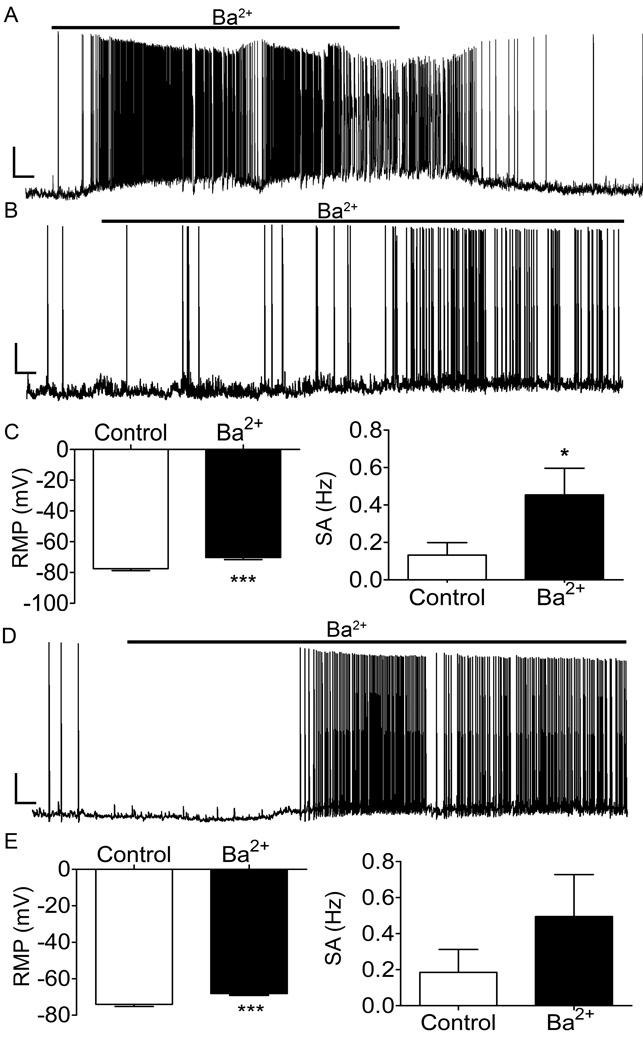

Background Kir2 leak conductance is known to shape neuronal excitability across many sensory modalities (Correia and Lang, 1990; Chen et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2004; Ruan et al., 2010). To elucidate the extent to which Kir2 channels shape the intrinsic membrane excitability of immature lamina I projection neurons, current clamp recordings were obtained from identified spino-PB (Figures 3A, B) and spino-PAG neurons (Figure 3D) in the intact spinal cord preparation at P3–P5. Spontaneous activity was recorded before and after bath administration of 200 µM Ba2+ to block Kir2 channels. Ba2+ application significantly depolarized the resting membrane potential (RMP) of both spino-PB and spino-PAG neurons (Figure 3C, left, p < 0.0001, paired t-test; Figure 3E, left, p < 0.0001) and significantly increased the rate of spontaneous action potential firing in spino-PB neurons (Figure 3C, right, p = 0.03). A similar trend was observed in spino-PAG neurons although this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 3E, right).

Figure 3. Ba2+ blockade of Kir2 channels depolarizes immature lamina I projection neurons and enhances spino-PB neuron spontaneous activity.

A, Representative trace showing a reversible increase in spontaneous action potential discharge in a spino-PB neuron in response to 200 µM Ba2+ bath application. Black bar, duration of Ba2+ application. Scale bars, 20 mV and 20 s. B, Representative trace of a spontaneously active spino-PB cell illustrating an increase of spontaneous action potential discharge in response to 200 µM Ba2+ bath application. Black bar, duration of Ba2+ application. Scale bars, 20 mV and 10 s. C, Ba2+ application significantly depolarizes the resting membrane potential (RMP) of spino-PB neurons (n = 32, 7 rats, p < 0.0001, paired t-test; left) and increases the rate of spontaneous activity (SA) (n = 32, 7 rats, p = 0.028, paired t-test; right). D, Representative trace of a spontaneously active spino-PAG neuron showing an increase of spontaneous action potential discharge in response to 200 µM Ba2+ bath application. Black bar, duration of Ba2+ application. Scale bars, 20 mV and 10 s. E, Ba2+ application significantly depolarizes spino-PAG RMP (n = 20, 4 rats, p < 0.0001, paired t-test; left) but did not significantly affect the frequency of spontaneous firing (n = 20, 4 rats, p = 0.09, paired t-test; right) in this population.

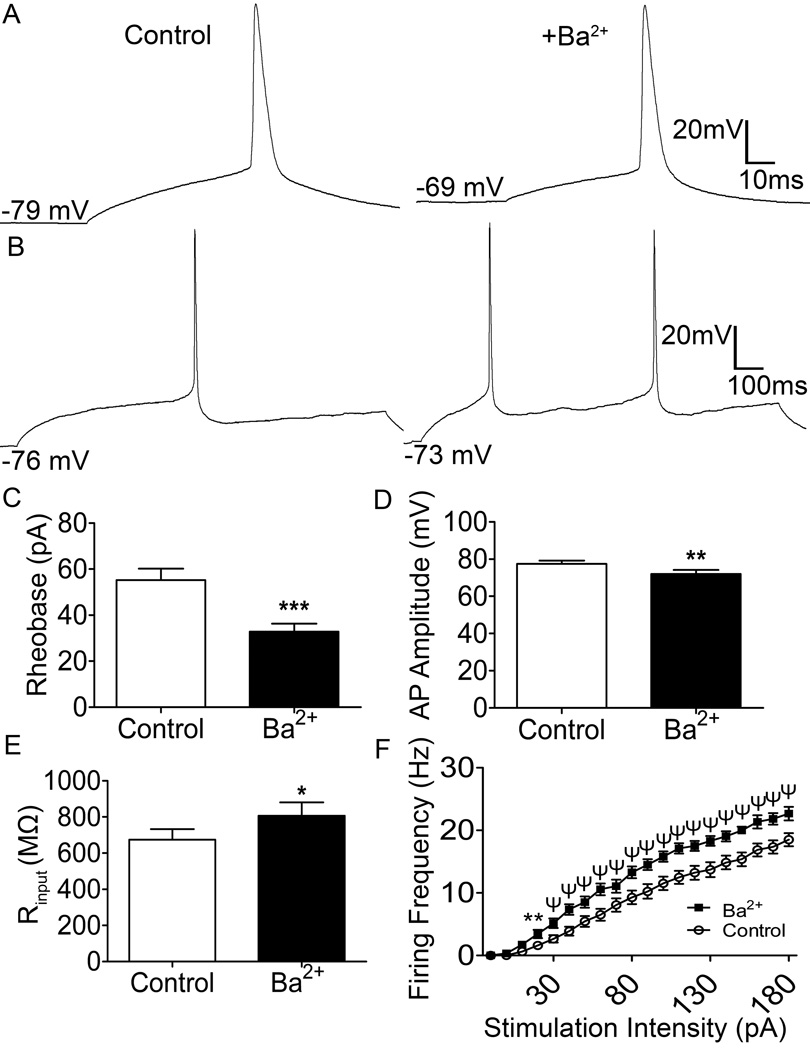

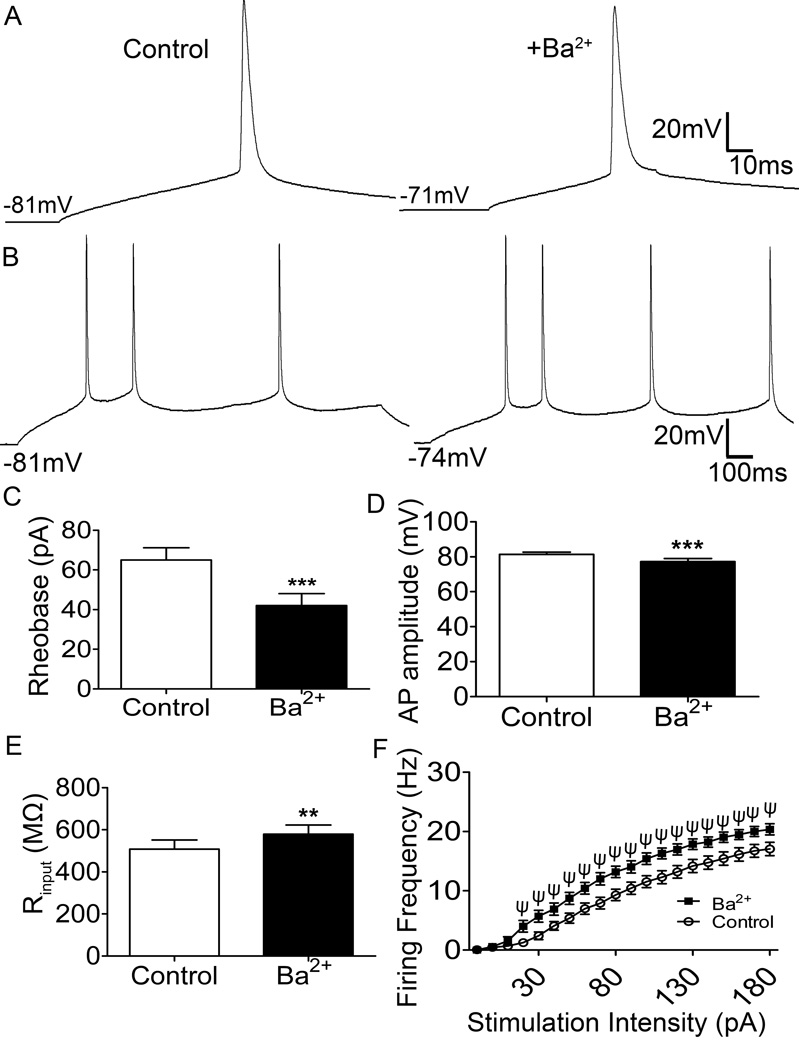

Ba2+ block of Kir2 channels in both spino-PB and spino-PAG neurons at physiological membrane potentials (Figures 4A, 5A) also significantly decreased the rheobase (Figure 4C, p < 0.0001; Figure 5C; p < 0.0001). In addition to the observed decrease in rheobase, the application of external Ba2+ also significantly decreased the amplitude of the evoked action potentials (Figure 4D, p = 0.0013; Figure 5D, p < 0.0001). These alterations were accompanied by a significant increase in input resistance (Figure 4E, p = 0.013; Figure 5E, p < 0.01) which indicates an overall reduction in background leak conductance. Finally, the ability of spino-PB and spino-PAG projection neurons to repetitively fire action potentials in response to a sustained depolarizing current injection was examined in the absence and presence of external Ba2+ (Figures 4B, 5B). Ba2+ application significantly enhanced the firing frequency of both populations of neonatal projection neurons when compared to control (Figure 4F, F(19,513) = 6.6, p < 0.001; Figure 5F, F(19,361) = 7.7, p < 0.001; two-way repeated measures ANOVA).

Figure 4. Ba2+ blockade of Kir2 channels enhances the intrinsic excitability of neonatal spino-PB neurons.

A, top, Representative traces of action potentials evoked via depolarizing current steps (5 pA steps, 80 ms duration) in the absence (left) and presence (right) of Ba2+. B, Representative traces of repetitive firing evoked by current steps (10 pA, 800 ms duration) in the absence (left) and presence (right) of Ba2+. C–E, Ba2+ application significantly reduces rheobase (p < 0.0001, paired t-test; C) and AP amplitude (p < 0.01, paired t-test; D), while enhancing membrane resistance (p < 0.05, paired t-test; E). F, Ba2+ application significantly enhances the firing frequency of immature spino-PB projection neurons (** p < 0.01; ψ p < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak post-tests). n = 32, 7 rats, for all comparisons.

Figure 5. Ba2+ application increases the intrinsic excitability of neonatal spino-PAG neurons.

A, Representative traces of action potentials evoked by depolarizing current steps (5 pA, 80 ms duration) in the absence (left) and presence (right) of Ba2+. B, Representative traces of repetitive firing evoked by intracellular current injection (10 pA steps, 800 ms duration) in the absence (left) and presence (right) of Ba2+. C–E, Ba2+ application significantly reduces rheobase (p < 0.0001, paired t-test; C) and AP amplitude (p < 0.0001, paired t-test; D) while membrane resistance was increased (p < 0.01, paired t-test; E). F, Ba2+ application significantly enhances the firing frequency of spino-PAG projection neurons during early life (ψ p < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak post-tests). n = 20, 4 rats, for all comparisons.

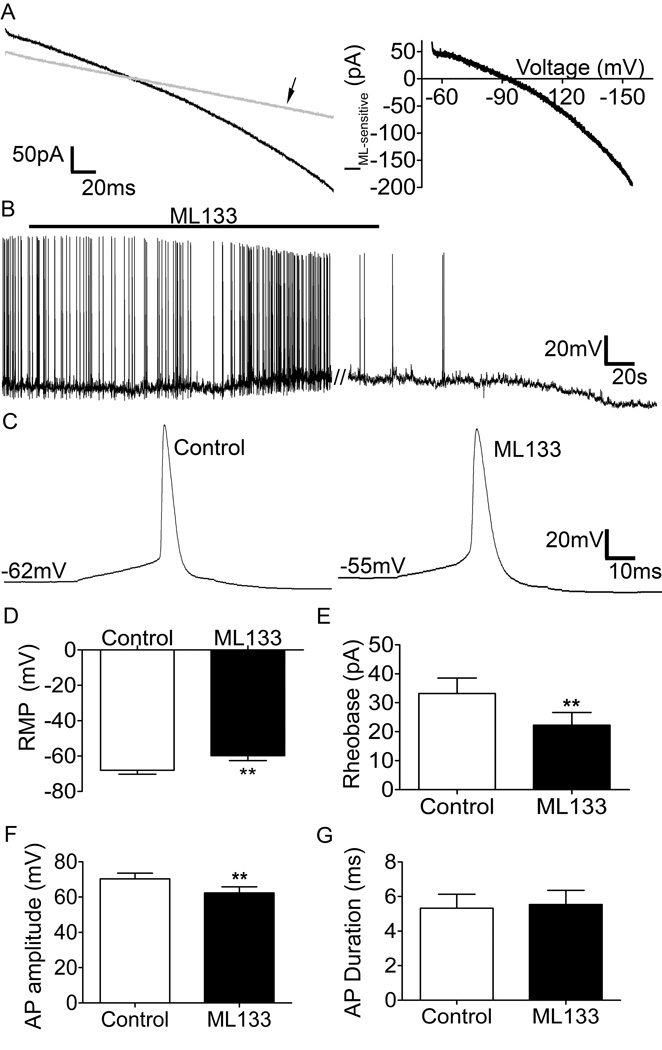

To exclude the possibility that the Ba2+ modulated the excitability of lamina I projection neurons via off-target effects on other ion channels, we next investigated whether the bath perfusion of a potent and selective Kir2 antagonist, ML133 (Wang et al., 2011), exerted a similar influence on the leak conductance and firing of immature spino-PB neurons. Under voltage-clamp conditions, the evoked whole-cell ramp currents were sensitive to 100 µM ML133 (Figure 6A, left) and subsequent electronic subtraction revealed an inward-rectifying K+ current (Figure 6A, right) similar to that obtained with Ba2+ perfusion. Importantly, ML133 increased spontaneous activity (Figure 6B), depolarized the RMP (Figure 6C, D, n = 11, 2 rats, for all comparisons, p < 0.01, paired t-test) and decreased rheobase (Figure 6E; p < 0.01, paired t-test) in immature spino-PB neurons. In addition, ML133 application significantly decreased the amplitude of evoked action potentials (Figure 6F, p < 0.01), but did not affect the AP duration (Figure 6G; p = 0.48, paired t-test). ML133 application also caused an increase in mean membrane resistance from 906 ± 138.1 MΩ to 1076 ± 140.8 MΩ, though the difference was not statistically significant (data not shown).

Figure 6. ML133 suppresses Kir2 currents and enhances intrinsic membrane excitability in immature spino-PB neurons.

A left, representative whole-cell current trace evoked by a 100 mV hyperpolarizing voltage ramp (from −55 mV to −155 mV) in the presence (arrow) and absence of the selective Kir2 channel antagonist ML133 (100 µM); A right, representative electronic subtraction yielding the ML133-sensitive (i.e. Kir2) current. B, Representative trace demonstrating a depolarizing shift in resting membrane potential (RMP) and increased spontaneous activity in response to 10 µM ML133 application (black bar). C, Representative action potentials evoked by depolarizing current steps (5 pA, 80 ms) in the absence (left) and presence (right) of ML133. D–G, ML133 application significantly depolarizes the RMP (p < 0.01, paired t-test; D), decreases rheobase (p < 0.01, paired t-test; E), decreases AP amplitude (p < 0.01, paired t-test; F), and has no effect on AP duration (p = 0.48, paired t-test, G). n = 11, 2 rats, for all comparisons.

In summation, these studies collectively demonstrate that spino-PB and spino-PAG projection neurons express similar levels of a Kir2-mediated leak conductance that suppresses intrinsic membrane excitability in a tonic manner during the early postnatal period.

Discussion

The level of activity in lamina I projection neurons can significantly influence pain perception (Mantyh et al., 1997; Nichols et al., 1999; Suzuki et al., 2002), as this population represents the major output of the spinal superficial dorsal horn (SDH) network (Hylden et al., 1989; Han et al., 1998; Todd, 2010). Despite their clear importance for nociceptive processing, surprisingly little is known about the specific ionic mechanisms governing the intrinsic excitability of lamina I projection neurons at any stage of postnatal development. Voltage-independent (i.e. “leak”) K+ channels, including classical inward-rectifying K+ (Kir2) channels, play a fundamental role in the regulation of ionic homeostasis, passive membrane properties and intrinsic excitability in a wide array of neurons and other excitable cells (Marder and Goaillard, 2006; Yang et al., 2010). While recent work has demonstrated that Kir2.1, 2.2, and 2.3 are heavily expressed in the SDH of both neonatal and adult rats (Li et al., 2013; Murata et al., 2016), these studies provide little specific information about functional Kir2 expression in projection neurons due to their low prevalence within lamina I (Todd, 2010). The present results identify, for the first time, Kir2 channels as key regulators of intrinsic membrane excitability in multiple populations of ascending spinal projection neurons during early life. By dampening the firing of these neurons in a tonic manner, Kir2 channels constitutively limit the flow of nociceptive information to the developing brain.

Therefore, it seems clear that fluctuations in Kir2 channel activity within neonatal projection neurons resulting from the action of neurotransmitters or neuromodulators could profoundly alter the “gain” of ascending nociceptive signaling. Notably, the magnitude of Kir2 current can be regulated by cholinergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission as well as lipid signaling (Wilson and Kawaguchi, 1996; Shen et al., 2007; Surmeier et al., 2007; Shi et al., 2008; Xie et al., 2008). In addition, the level of Kir2 conductance in developing projection neurons could be influenced by noxious somatosensory experience during early life, as previous work has demonstrated that neonatal surgical injury enhances Kir current expression in GABAergic lamina II interneurons of the adult mouse spinal cord and thus dampens their intrinsic excitability (Li and Baccei, 2014). Nonetheless, the degree to which persistent alterations in the expression of Kir2, or other leak channels, contribute to the long-term changes in pain sensitivity following early tissue damage (Walker et al., 2016) remains unexplored.

Spontaneous activity in ascending projection neurons during early life (Li and Baccei, 2012) may have significant consequences for the appropriate formation of supraspinal nociceptive circuits, as documented in other sensory systems (Hubel and Wiesel, 1970; Yu et al., 2004), where inappropriate spatio-temporal action potential firing can persistently alter network connectivity and synchronization (Brunjes, 1994; Katz and Shatz, 1996; Tritsch et al., 2007). Therefore, given their potent ability to regulate activity in neonatal projection neurons, Kir2 channels may exert prolonged effects on the functional organization of developing pain pathways. Indeed, Kir2.1 overexpression in neurons is known to modify axon growth, axon terminal arborization, circuit integration and synaptic pruning (Hua et al., 2005; Lorenzetto et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2010; Matsumoto et al., 2016), as well as disrupt the normal development of sensory networks in the CNS (Katz and Shatz, 1996; Yu et al., 2004; Tritsch et al., 2007). Kir2 channels could also shape the maturation of nociceptive pathways at the level of the primary afferents, as sensory neurons highly express Kir2.x channels (Murata et al., 2016) and Kir2.1 overexpression in this population reduces hyperalgesia after peripheral nerve damage (Ma et al., 2010).

Our prior work suggests that the levels of spontaneous activity in ascending pain pathways varies depending on the brain region targeted, as the prevalence of spontaneously active neurons is significantly higher in spino-PB neurons compared to spino-PAG projection neurons (Li and Baccei, 2012). While the present study confirms a higher prevalence of spontaneous activity in the spino-PB population (Figure 1), the overall rate of spontaneous firing was in fact similar between groups (Figure 3C, E). This suggests that while spino-PB neurons are more likely to be spontaneously active at rest, they fire at a lower rate compared to the small subset of spontaneously firing spino-PAG cells. Notably, the two populations appear to also exhibit similar peak repetitive firing rates at the stimulus intensities examined (Figures 4F, 5F). Collectively, the present data demonstrate that the difference in the prevalence of spontaneous activity cannot be explained by a differential expression of Kir2 conductance between the two populations, as Kir2-mediated current was found in similar amounts in spino-PB and spino-PAG neurons (Figure 2B). In addition, the two groups of projection neurons displayed a similar increase of intrinsic membrane excitability upon blocking Kir2 currents via Ba2+ application (Figures 3–5), which is consistent with prior studies of Kir2 channels in multiple subtypes of CNS neurons (Standen and Stanfield, 1978; Day et al., 2005; Li et al., 2013) including interneurons within the spinal superficial dorsal horn (Li et al., 2013). While the sensitivity to Ba2+ and ML133 point to the expression of Kir2.1–2.3 in projection neurons (Hibino et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011), as reported previously within lamina I interneurons (Li et al., 2013), the exact Kir2 isoforms that regulate the firing of spino-PB and spino-PAG neurons remain to be identified.

Nonetheless, it remains possible that cell type-specific expression of other leak K+ channels, such as the two-pore potassium (K2P) leak channels that are strongly expressed in the developing rat dorsal horn (Blankenship et al., 2013), underlies the difference in spontaneous activity across various populations of immature projection neurons. Alternatively, the higher prevalence of spontaneous firing seen in spino-PB neurons could potentially reflect a greater expression of a leak Na+ channel that provides constitutive inward current to facilitate action potential generation. A voltage-independent sodium leak channel, NALCN, has recently been shown to be expressed in the rodent CNS, as well as in central pattern generating neurons of Lymnea stagnalis and C. elegans (Lee et al., 1999; Lu et al., 2007; Lu and Feng, 2011; Gao et al., 2015). However, the degree to which NALCN modulates the excitability of neurons within peripheral or central nociceptive pathways remains completely unknown. Clearly, future investigations are needed to elucidate the full complement of leak ion channels that shape the output of the spinal nociceptive circuit throughout life.

Conclusions

The present evidence demonstrates that tonic Kir2 current dampens the intrinsic membrane excitability of neonatal spino-PB and spino-PAG projection neurons to a similar degree, suggesting that the higher prevalence of spontaneous activity previously reported in the spino-PB population cannot be explained by a weaker expression of Kir2 channels.

Nevertheless, the present results clearly indicate that the output of the immature spinal pain circuit is strongly governed by Kir2 conductance, which is predicted to moderate the ascending transmission of nociceptive signals to the developing brain and thus constrain pain sensitivity during a critical period of early life.

Highlights.

Neonatal rat spino-PB and spino-PAG neurons express similar leak conductance through inward-rectifying K+ (Kir) channels.

Block of Kir2 channels significantly enhances the intrinsic membrane excitability of both spino-PB and spino-PAG neurons.

Kir2 channels may thus constitutively diminish nociceptive signal transmission from the neonatal spinal cord to the brain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NS072202 to MLB). The authors would like to thank Mrs. Elizabeth Serafin for technical support during the project.

Abbreviations

- SDH

Superficial dorsal horn

- PB

Parabrachial nucleus

- PAG

Periaqueductal gray

- Kir

Classical inward-rectifying potassium channel

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Khater KM, Todd AJ. Collateral projections of neurons in laminae I, III, and IV of rat spinal cord to thalamus, periaqueductal gray matter, and lateral parabrachial area. J Comp Neurol. 2009;515:629–646. doi: 10.1002/cne.22081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew D. Sensitization of lamina I spinoparabrachial neurons parallels heat hyperalgesia in the chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain. J Physiol. 2009;587:2005–2017. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.170290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bester H, Chapman V, Besson JM, Bernard JF. Physiological properties of the lamina I spinoparabrachial neurons in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2239–2259. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.4.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship ML, Coyle DE, Baccei ML. Transcriptional expression of voltage-gated Na(+) and voltage-independent K(+) channels in the developing rat superficial dorsal horn. Neuroscience. 2013;231:305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.11.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunjes PC. Unilateral naris closure and olfactory system development. Brain Res Rev. 1994;19:146–160. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Yu YC, Zhao JW, Yang XL. Inwardly rectifying potassium channels in rat retinal ganglion cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:956–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee WA, Amarillo Y, Chiu J, Chow A, Lau D, McCormack T, Moreno H, Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Pountney D, Saganich M, Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Rudy B. Molecular diversity of K+ channels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;868:233–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia MJ, Lang DG. An electrophysiological comparison of solitary type I and type II vestibular hair cells. Neurosci Lett. 1990;116:106–111. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90394-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day M, Carr DB, Ulrich S, Ilijic E, Tkatch T, Surmeier DJ. Dendritic excitability of mouse frontal cortex pyramidal neurons is shaped by the interaction among HCN, Kir2, and Kleak channels. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8776–8787. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2650-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derjean D, Bertrand S, Le Masson G, Landry M, Morisset V, Nagy F. Dynamic balance of metabotropic inputs causes dorsal horn neurons to switch functional states. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:274–281. doi: 10.1038/nn1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman HS, Allen TB, MacDermott AB. The distribution of neurons expressing calcium-permeable AMPA receptors in the superficial laminae of the spinal cord dorsal horn. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2081–2089. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02081.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Xie L, Kawano T, Po MD, Guan S, Zhen M, Pirri JK, Alkema MJ. The NCA sodium leak channel is required for persistent motor circuit activity that sustains locomotion. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6323. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauriau C, Bernard JF. Pain pathways and parabrachial circuits in the rat. Exp Physiol. 2002;87:251–258. doi: 10.1113/eph8702357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudt TJ, Perl ER. Correlations between neuronal morphology and electrophysiological features in the rodent superficial dorsal horn. J Physiol. 2002;540:189–207. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han ZS, Zhang ET, Craig AD. Nociceptive and thermoreceptive lamina I neurons are anatomically distinct. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:218–225. doi: 10.1038/665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinricher MM, Tavares I, Leith JL, Lumb BM. Descending control of nociception: Specificity, recruitment and plasticity. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino H, Inanobe A, Furutani K. Inwardly rectifying potassium channels: their structure, function, and physiological roles. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:291–366. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu HJ, Gereau RWt. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 regulates excitability and Kv4.2-containing K(+) channels primarily in excitatory neurons of the spinal dorsal horn. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:3010–3021. doi: 10.1152/jn.01050.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua JY, Smear MC, Baier H, Smith SJ. Regulation of axon growth in vivo by activity-based competition. Nature. 2005;434:1022–1026. doi: 10.1038/nature03409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. The period of susceptibility to the physiological effects of unilateral eye closure in kittens. J Physiol. 1970;206:419–436. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylden JL, Anton F, Nahin RL. Spinal lamina I projection neurons in the rat: collateral innervation of parabrachial area and thalamus. Neuroscience. 1989;28:27–37. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhamandas JH, Petrov T, Harris KH, Vu T, Krukoff TL. Parabrachial nucleus projection to the amygdala in the rat: electrophysiological and anatomical observations. Brain Res Bull. 1996;39:115–126. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)02084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC, Shatz CJ. Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science. 1996;274:1133–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Cribbs LL, Perez-Reyes E. Cloning of a novel four repeat protein related to voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. FEBS Lett. 1999;445:231–236. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Baccei ML. Pacemaker neurons within newborn spinal pain circuits. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9010–9022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6555-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Baccei ML. Developmental regulation of membrane excitability in rat spinal lamina I projection neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2012;107:2604–2614. doi: 10.1152/jn.00899.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Baccei ML. Neonatal tissue injury reduces the intrinsic excitability of adult mouse superficial dorsal horn neurons. Neuroscience. 2014;256:392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Blankenship ML, Baccei ML. Inward-rectifying potassium (Kir) channels regulate pacemaker activity in spinal nociceptive circuits during early life. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3352–3362. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4365-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Kritzer E, Ford NC, Arbabi S, Baccei ML. Connectivity of pacemaker neurons in the neonatal rat superficial dorsal horn. J Comp Neurol. 2015;523:1038–1053. doi: 10.1002/cne.23706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima D, Mendes-Ribeiro JA, Coimbra A. The spino-latero-reticular system of the rat: projections from the superficial dorsal horn and structural characterization of marginal neurons involved. Neuroscience. 1991;45:137–152. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90110-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CW, Sim S, Ainsworth A, Okada M, Kelsch W, Lois C. Genetically increased cell-intrinsic excitability enhances neuronal integration into adult brain circuits. Neuron. 2010;65:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GX, Derst C, Schlichthorl G, Heinen S, Seebohm G, Bruggemann A, Kummer W, Veh RW, Daut J, Preisig-Muller R. Comparison of cloned Kir2 channels with native inward rectifier K+ channels from guinea-pig cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 2001;532:115–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0115g.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetto E, Caselli L, Feng G, Yuan W, Nerbonne JM, Sanes JR, Buffelli M. Genetic perturbation of postsynaptic activity regulates synapse elimination in developing cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16475–16480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907298106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Su Y, Das S, Liu J, Xia J, Ren D. The neuronal channel NALCN contributes resting sodium permeability and is required for normal respiratory rhythm. Cell. 2007;129:371–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu TZ, Feng ZP. A sodium leak current regulates pacemaker activity of adult central pattern generator neurons in Lymnaea stagnalis. PloS one. 2011;6:e18745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Rosenzweig J, Zhang P, Johns DC, LaMotte RH. Expression of inwardly rectifying potassium channels by an inducible adenoviral vector reduced the neuronal hyperexcitability and hyperalgesia produced by chronic compression of the spinal ganglion. Mol Pain. 2010;6:65. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantyh PW, Rogers SD, Honore P, Allen BJ, Ghilardi JR, Li J, Daughters RS, Lappi DA, Wiley RG, Simone DA. Inhibition of hyperalgesia by ablation of lamina I spinal neurons expressing the substance P receptor. Science. 1997;278:275–279. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Goaillard JM. Variability, compensation and homeostasis in neuron and network function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:563–574. doi: 10.1038/nrn1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto N, Hoshiko M, Sugo N, Fukazawa Y, Yamamoto N. Synapse-dependent and independent mechanisms of thalamocortical axon branching are regulated by neuronal activity. Dev Neurobiol. 2016;76:323–336. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murase K, Randic M. Electrophysiological properties of rat spinal dorsal horn neurones in vitro: calcium-dependent action potentials. J Physiol. 1983;334:141–153. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Yasaka T, Takano M, Ishihara K. Neuronal and glial expression of inward rectifier potassium channel subunits Kir2.x in rat dorsal root ganglion and spinal cord. Neurosci Lett. 2016;617:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols ML, Allen BJ, Rogers SD, Ghilardi JR, Honore P, Luger NM, Finke MP, Li J, Lappi DA, Simone DA, Mantyh PW. Transmission of chronic nociception by spinal neurons expressing the substance P receptor. Science. 1999;286:1558–1561. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott SA, De Koninck Y. Four cell types with distinctive membrane properties and morphologies in lamina I of the spinal dorsal horn of the adult rat. J Physiol. 2002;539:817–836. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DD. Psychological and neural mechanisms of the affective dimension of pain. Science. 2000;288:1769–1772. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Q, Chen D, Wang Z, Chi F, He J, Wang J, Yin S. Effects of Kir2.1 gene transfection in cochlear hair cells and application of neurotrophic factors on survival and neurite growth of co-cultured cochlear spiral ganglion neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010;43:326–339. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscheweyh R, Ikeda H, Heinke B, Sandkuhler J. Distinctive membrane and discharge properties of rat spinal lamina I projection neurones in vitro. J Physiol. 2004;555:527–543. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.054049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safronov BV, Pinto V, Derkach VA. High-resolution single-cell imaging for functional studies in the whole brain and spinal cord and thick tissue blocks using light-emitting diode illumination. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;164:292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda FV, Pablo Cid L, Teulon J, Niemeyer MI. Molecular aspects of structure, gating, and physiology of pH-sensitive background K2P and Kir K+-transport channels. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:179–217. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Tian X, Day M, Ulrich S, Tkatch T, Nathanson NM, Surmeier DJ. Cholinergic modulation of Kir2 channels selectively elevates dendritic excitability in striatopallidal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1458–1466. doi: 10.1038/nn1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi TJ, Liu SX, Hammarberg H, Watanabe M, Xu ZQ, Hokfelt T. Phospholipase C{beta}3 in mouse and human dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord is a possible target for treatment of neuropathic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20004–20008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810899105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standen NB, Stanfield PR. A potential- and time-dependent blockade of inward rectification in frog skeletal muscle fibres by barium and strontium ions. J Physiol. 1978;280:169–191. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier DJ, Ding J, Day M, Wang Z, Shen W. D1 and D2 dopamine-receptor modulation of striatal glutamatergic signaling in striatal medium spiny neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki R, Morcuende S, Webber M, Hunt SP, Dickenson AH. Superficial NK1-expressing neurons control spinal excitability through activation of descending pathways. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1319–1326. doi: 10.1038/nn966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szűcs P, Pinto V, Safronov BV. Advanced technique of infrared LED imaging of unstained cells and intracellular structures in isolated spinal cord, brainstem, ganglia and cerebellum. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;177:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd AJ. Neuronal circuitry for pain processing in the dorsal horn. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:823–836. doi: 10.1038/nrn2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritsch NX, Yi E, Gale JE, Glowatzki E, Bergles DE. The origin of spontaneous activity in the developing auditory system. Nature. 2007;450:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature06233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BA. Pain and emotion interactions in subregions of the cingulate gyrus. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:533–544. doi: 10.1038/nrn1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SM, Beggs S, Baccei ML. Persistent changes in peripheral and spinal nociceptive processing after early tissue injury. Exp Neurol. 2016;275(Pt 2):253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HR, Wu M, Yu H, Long S, Stevens A, Engers DW, Sackin H, Daniels JS, Dawson ES, Hopkins CR, Lindsley CW, Li M, McManus OB. Selective inhibition of the K(ir)2 family of inward rectifier potassium channels by a small molecule probe: the discovery, SAR, and pharmacological characterization of ML133. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:845–856. doi: 10.1021/cb200146a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CJ, Kawaguchi Y. The origins of two-state spontaneous membrane potential fluctuations of neostriatal spiny neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2397–2410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02397.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie LH, John SA, Ribalet B, Weiss JN. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) regulation of strong inward rectifier Kir2.1 channels: multilevel positive cooperativity. J Physiol. 2008;586:1833–1848. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang KC, Foeger NC, Marionneau C, Jay PY, McMullen JR, Nerbonne JM. Homeostatic regulation of electrical excitability in physiological cardiac hypertrophy. J Physiol. 2010;588:5015–5032. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.197418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasaka T, Tiong SY, Hughes DI, Riddell JS, Todd AJ. Populations of inhibitory and excitatory interneurons in lamina II of the adult rat spinal dorsal horn revealed by a combined electrophysiological and anatomical approach. Pain. 2010;151:475–488. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young CC, Stegen M, Bernard R, Muller M, Bischofberger J, Veh RW, Haas CA, Wolfart J. Upregulation of inward rectifier K+ (Kir2) channels in dentate gyrus granule cells in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Physiol. 2009;587:4213–4233. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.170746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CR, Power J, Barnea G, O'Donnell S, Brown HEV, Osborne J, Axel R, Gogos JA. Spontaneous Neural Activity Is Required for the Establishment and Maintenance of the Olfactory Sensory Map. Neuron. 2004;42:553–566. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]