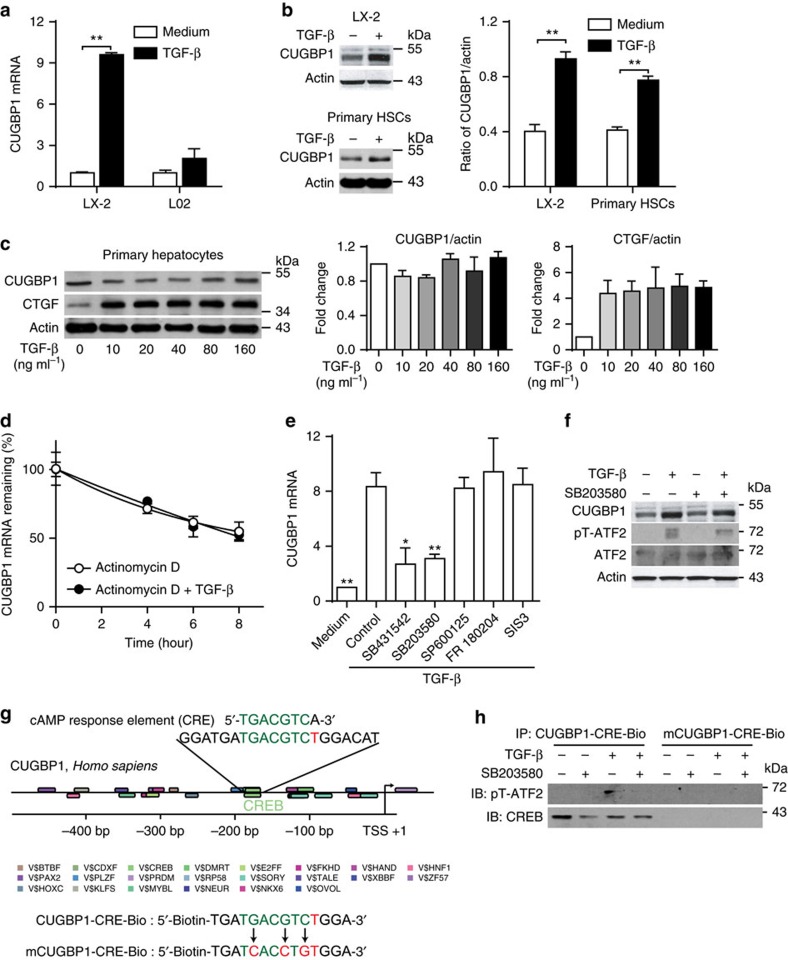

Figure 2. TGF-β increases CUGBP1 expression in HSCs via p38 MAPK.

(a) Quantitative PCR analyses of CUGBP1 mRNA from the human hepatic stellate cell line LX-2 or human hepatocyte L02 cells treated with or without 5 ng ml−1 TGF-β for 6 h (mean±s.e.m.; n=3, **P<0.01 by Student's t-test). (b,c) Western blot analyses of CUGBP1 from LX-2 cells, primary mouse HSCs (b), and primary mouse hepatocytes (c) treated with or without 5 ng ml−1 TGF-β for 24 h. The data are representative of three independent experiments (mean±s.e.m.; n=3, **P<0.01 by Student's t-test). (d,e) LX-2 cells were treated with actinomycin D (1 μg ml−1) and with or without 5 ng ml−1 TGF-β for indicated time intervals (d). LX-2 cells were treated with or without SB431542 (10 μM), SB203580 (10 μM), SP600125 (10 μM), FR180204 (10 μM) or SIS3 (20 μM), following 5 ng ml−1 TGF-β treatment for 6 h (e). And then quantitative PCR was carried out to detect the remaining mRNA expression of CUGBP1. (mean±s.e.m.; n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's test). (f) Western blot analyses of LX-2 cells treated with or without SB431542, following 5 ng ml−1 TGF-β treatment for 24 h. (g) Gene2promotor analyses of promoter and transcription factors of human CUGBP1 gene. (h) Probe pull down assay was performed by mixing CUGBP1-CRE-Bio or mCUGBP1-CRE-Bio with total cell extracts from LX-2 cells treated as in f. Precipitates were prepared for Western blotting using SoftLink Soft Release avidin resin. The data in f and h are representative of two independent experiments.