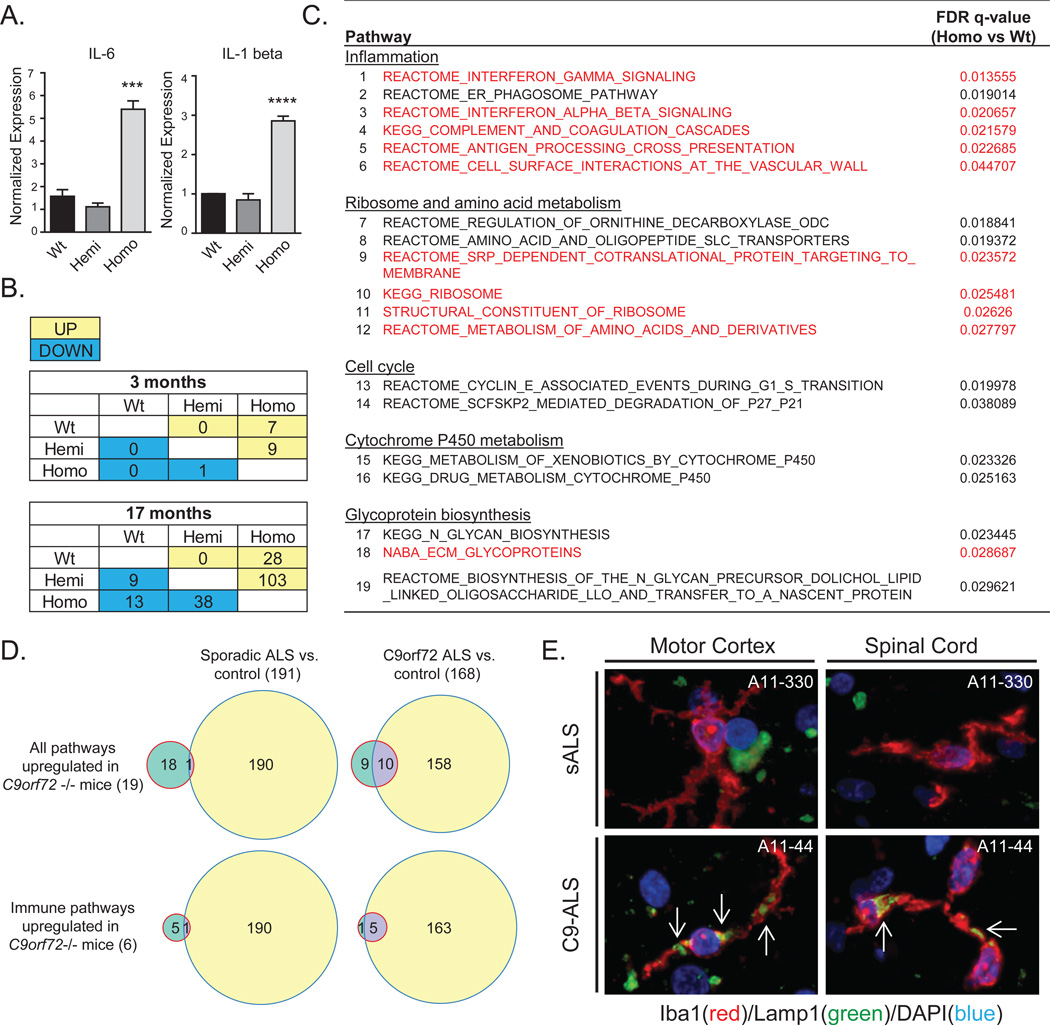

Fig. 4. Neuroinflammation in C9orf72−/− mice and C9orf72 expansion patient tissue.

(A) qRT-PCR of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and IL-1 beta) in microglia isolated from C9orf72−/− mice. (***p=0.0007; ****p=<0.0001, one-way ANOVA). (B) Tables showing the number of up and down-regulated pathways on GSEA (FDR<0.05) of RNA-seq from 3 and 17 month old lumbar spinal cords. (C) Table of up-regulated pathways in C9orf72−/− vs. C9orf72+/− and wild-type mouse spinal cords (FDR<0.05) at 17 months. Pathways up-regulated in both C9orf72−/− mice and human C9-ALS brain tissue are highlighted in red. (D) Top: Venn diagrams showing overlap between the 19 up-regulated pathways in C9orf72−/− mice from (C), and those up-regulated in cortex or cerebellum of sporadic ALS (left), or C9orf72 ALS (right). Bottom: Venn diagrams for the immune pathways from (C). (E) Human motor cortex and spinal cord from C9-ALS and sALS cases double-labelled with Iba1 (red) to identify microglia, and Lamp1 (green). Large accumulations of Lamp1 immunoreactivity (white arrows) were detected in activated microglia of C9-ALS but not sALS tissue.