Abstract

Molecules of the coagulation pathway predispose patients to cancer-associated thrombosis and also trigger intracellular signaling pathways that promote cancer progression. The primary transcript of Tissue Factor, the main physiologic trigger of blood clotting, can undergo alternative splicing yielding a secreted variant, termed asTF (alternatively spliced Tissue Factor). asTF is not required for normal hemostasis, but its expression levels positively correlate with advanced tumor stages in several cancers, including pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The asTF-over-expressing pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell line Pt45.P1/asTF+ and its parent cell line Pt45.P1 were tested for growth and mobility under normoxic conditions that model early stage tumors, and in the hypoxic environment of late-stage cancers. asTF over-expression in Pt45.P1 cells conveys increased proliferative ability. According to cell cycle analysis, the major fraction of Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells reside in the dividing G2/M phase of the cell cycle, whereas the parental Pt45.P1 cells are mostly confined to the quiescent G0/G1 phase. asTF over-expression is also associated with significantly higher mobility in cells plated under either normoxia or hypoxia. A hypoxic environment leads to upregulation of Carbonic Anhydrase IX (CAIX), which is more pronounced in Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells. Inhibition of CAIX by the compound U-104 significantly decreases cell growth and mobility of Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells in hypoxia, but not in normoxia. U-104 also reduces the growth of Pt45.P1/asTF+ orthotopic tumors in nude mice. CAIX is a novel downstream mediator of asTF in pancreatic cancer, particularly under hypoxic conditions that model late-stage tumor micro-environment.

Keywords: cancer progression, hypoxia, anchorage independence, tissue factor, cell division, migration

Introduction

The genetic programs of tumor progression are activated downstream of deregulated growth and survival signals in cancers, but not in benign tumors 1. They direct tissue destruction and dissemination. There is a functional link between the programs of tumor progression and the hemostatic system 2, as both coagulopathy and neoangiogenesis are important features of the vasculature associated with malignancy 3–5. Blood clotting disorders ranging from thrombosis to hemorrhage lead to poor prognosis in cancer patients, and hemostatic system inhibitors have long been proposed as a means to control tumor progression 6. Beyond coagulopathies, the components of the hemostatic system also directly affect the course of the disease via tumor cell proliferation, survival, and dissemination. For instance, in the absence of fibrinogen, lung metastases in mice with melanoma are significantly reduced 7. Thrombin and its receptor (PAR-1) increase the invasive phenotype in breast cancer 8. Tissue Factor (TF) and the complex TF/FVIIa/FXa contribute to tumor progression in breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and other malignancies 8, 9.

TF is known to promote the expression of metastasis genes, which directly mediate tumor progression 10,11. The primary transcript of TF, the main physiological trigger of blood coagulation, undergoes alternative splicing to yield a variant form, termed asTF (alternatively spliced Tissue Factor). asTF is devoid of the transmembrane domain and hence can be secreted 10. Whereas TF expression positively correlates with advanced tumor stages and thrombosis, asTF is not required for normal hemostasis 11, but its expression levels are higher in patients with more aggressive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. asTF acts as a cell inducer by binding β-1 Integrins, which are selectively activated by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF) 12,13. Although asTF expression is associated with increased tumor cell proliferation, metastases, and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer 11,14,15, the underlying mechanisms of tumor progression at late stages, where it is highly expressed, are yet to be fully delineated.

Once pancreatic cancer has progressed, asTF acts in an environment of low glucose, high lactate, and low pH. In this setting, the cancer cells maintain their homeostasis in part through the actions of Carbonic Anhydrases. These enzymes catalyze the reversible hydration of carbon dioxide, and thus contribute to pH maintenance. Carbonic Anhydrase IX (CAIX) is a transmembrane protein that may be over-expressed in hypoxic cancer cells as a result of increased glycolysis and acidic pH, and was recently proposed to play a major role in the pathobiology of pancreatic cancer 16. While increasing survival by preventing an intracellular drop in pH, CAIX in turn makes the extracellular space more acidic and through this process could also affect cancer cell motility. At late cancer stages, tumor-promoting proteins such as asTF may in part act through CAIX. Indeed, we showed that asTF overexpression in pancreatic cancer cells upregulates the expression of VEGF 15, a gene that, like CAIX, is regulated by HIF-117.

To better understand the mechanisms by which asTF promotes tumor progression in late-stage pancreatic cancer, we tested the asTF-over-expressing pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell line Pt45.P1/asTF+ and the parent cell Pt45.P1 for proliferative potential and mobility under a normoxic, high glucose environment that models early stage tumors, and a hypoxic, energy-deprived, low pH environment that recapitulates the milieu of late-stage tumors.

Methods

Cell Culture

The human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell line Pt45.P1 and the Pt45.P1 derived, asTF-over-expressing cell line Pt45.P1/asTF+ were cultured in high glucose (1000 mg/l) DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Fisher Scientific), HEPES (Gibco), sodium pyruvate (Sigma) and the selecting antibiotic (Zeocin) as appropriate. Early stage cell culture conditions (normoxic, physiologic pH, high glucose) were characterized by 5% CO2, ambient O2, 1000 mg/l glucose and 0 mM lactate, whereas late stage conditions (hypoxic, low glucose/high lactate) comprised 20% CO2, 1% O2, 0 mg/l glucose and 5 mM lactate in BME medium (Gibco). We note that Pt45.P1 cells were previously described to carry KRAS mutation, a genetic hallmark of PDAC 18.

Protein Expression

Cell lysates were collected 48 h after seeding the cells at 0.5 × 105/well in 24-well plates under early stage conditions (5% CO2, ambient O2, 1000 mg/ml glucose) or advanced stage conditions (20% CO2, 1% O2, no glucose, 5 mM lactate). For generating chemical hypoxia as a positive control, HeLa cells were treated with 100 μM CoCl2 for 48 h before lysing. The protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce BCA assay, and 15 μg of protein was loaded per lane on 8% SDS PAGE. The separated proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane, blocked with 5% nonfat milk, probed with antibodies to asTF (rabbit monoclonal RabMab1) 19, vimentin (rabbit mAb, Cell Signaling), β-actin (rabbit, Cell Signaling), HIF-1α (rabbit pAb, Bethyl Laboratories), HIF-2α (rabbit pAb, GeneTex) CAIX (mouse mAb, GeneTex), or CAXII (goat pAb, Acris), followed by probing with the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad) and developed using ECL and H2O2.

Cell Proliferation Assay

Pt45.P1 and Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells were seeded in triplicates under early stage or late stage conditions in 96-well plates at a density of 2,000 cells/well. The cell abundance was measured on days 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 using Cell Proliferation Reagent WST-1 (Roche), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. WST-1 (4-[3-(4-Iodophenyl)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-5-tetrazolio]-1,3-benzene disulfonate) is taken up by live cells and cleaved by enzymes of the intermediary metabolism to formazan, which is retained intracellularly. This generates absorbance at 420–480 nm that can be directly correlated to the levels of viable cells in the system.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Pt45.P1 and Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells were seeded in 24-well plates either for adhesion (directly on the plastic surface of the plate) or under non-adherent conditions (on a layer of 0.015 μg/mm2 poly-HEMA 20, 21, at a minimum density of 100,000 cells/well. 72 h after plating, the cells were harvested and stained with propidium iodide (Sigma) 22, and were analyzed for cell cycle stage using FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Gap Closure (Wound Healing) Assay

Pt45.P1 and Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 0.1×106 cells/well. After 1–1.5 days, the cells had adhered and reached confluence, and the plates were scratched at the center of each well using a P200 pipet tip. To control for possible confounding effects by cell division, the assay was performed in the presence or absence of 2 μM thymidine (a G1/S blocker of cell cycle progression). Photographs were taken at 0, 18, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. The wells were quantitatively analyzed for gap closure activity by determining the area (in pixels) left unoccupied using the software ImageJ. The area at 0 hours was set to 100%.

Pharmacologic Inhibition of CAIX

To evaluate the contributions by CAIX to asTF-mediated tumor progression, functional assays were performed in the presence or absence of the carbonic anhydrase IX and XII inhibitor U-104 (EMD Millipore) or vehicle control (0.15% DMSO). The drug concentration was 75 μM, applied to Pt45.P1 and Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells.

Mouse Tumor Model

All animal procedures and studies were carried out in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee, University of Cincinnati. Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells (1×106 in 20 μL PBS) were orthotopically implanted into the pancreata of nude mice (age: 12–14 weeks; source: Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN; n = 8 per group, (one mouse was lost in the treatment group due to severe complications). Eight weeks after implantation, the mice were injected with U-104 (Selleck Chemicals) or vehicle control. U-104 was solubilized in 55.6% PEG 400, 11.1% ethanol and 33.3% water at 5 mg/ml, and then administered at 100 μl/dose intra-peritoneally, daily over a period of four weeks as described 19,20.

Results

CAIX is a downstream target of asTF. Because asTF expression is significantly upregulated in patients with late-stage pancreatic cancer 11, it is important to better delineate the downstream mechanisms through which it may promote tumor progression. Whereas conventional cell culture conditions aim to impart high growth capacity to cancer cells that may inform on early transformation, they do not suitably reflect the microenvironment of late-stage cancer lesions. We therefore analyzed Pt45.P1/asTF+ and Pt45.P1 lysates for the expression of specific proteins under normoxic, high glucose conditions that model early-stage tumors and in the hypoxic, high lactate environment of late-stage cancers (Figure 1A). HIF-2α was selectively expressed by Pt45.P1 cells that have a low basal level of asTF expression, whereas over-expression of asTF was accompanied by negligible HIF-2α expression. Although Pt45.P1 cells and Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells had comparable expression levels of HIF-1α, hypoxia-induced expression of CAIX (a known downstream target of HIF-1α) was significantly more pronounced in Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells compared to Pt45.P1 cells (Figure 1B). As we previously described, levels of full-length TF (flTF) do not increase in response to asTF overexpression in Pt45.P1 cells under normoxic conditions 11,23; the same was observed under hypoxic conditions (not shown). CAIX is an enzyme inducible by the lack of oxygen that plays important roles in maintaining intracellular pH and increasing cancer cell invasiveness. asTF favors a signaling pathway associated with HIF-1α over HIF-2α, and this may induce CAIX in a late-stage tumor environment. No appreciable levels of CAXII were detected in either Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells or Pt45.P1 cells under normoxic or hypoxic conditions (not shown).

Figure 1. Up-regulation of CAIX by asTF over-expression.

A) Cell culture conditions for modeling early stage or late stage pancreatic cancer progression. B) Expression of the hypoxia-associated proteins HIF-1α (117 kD), HIF-2α (118 kD), and CAIX (55 kD) in early (norm) or late stage (hyp) environments. β-Actin served as a loading control. HeLa cells treated with 100 μM CoCl2 were used as a positive control for hypoxia-induced gene expression. “env,” the environment under which the cells were kept for 48 hours before lysing, with “hyp” indicating hypoxic/low glucose and “norm” indicating normoxic/high glucose. The bottom panel shows the over-expression of asTF in Pt45.P1 cells, vimentin 18, and the loading control β-Actin.

Under late-stage tumor conditions, CAIX contributes to asTF-induced cell cycle progression

To test the effect of asTF overexpression on cell division, Pt45.P1 and Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells were assessed for cell proliferation using a colorimetric assay. Over a period of four days, under both early- and late-stage conditions, the Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells showed a significantly higher rate of proliferation compared to Pt45.P1 cells (Figure 2A, B). U-104, a benzene-sulphonamide, is a pharmacologic inhibitor of Carbonic Anhydrase IX and XII 24,25. The proliferation rate of Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells under –late-stage conditions was decreased in the presence of U-104. The drug did not affect the distribution of the cell cycle phases in Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells in early stage, or of Pt45.P1 cells in early or late-stage environments (Figure 2C–F).

Figure 2. Cell proliferation in normoxia and hypoxia.

Pt45.P1 and Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells were plated in triplicates in 96-well plates in A) the early stage environment (5% CO2, ambient O2, 1000 mg/l glucose, 0 mM lactate) or B) the advanced stage environment (20% CO2, 1% O2, 0 mg/l glucose, 5 mM lactate). C–F) Effects of the CAIX inhibitor U-104 (75 μM) on cell proliferation by Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells (C,E) or Pt45.P1 cells (D,F) under advanced stage (C,D) or early stage conditions (E,F). At the indicated times, WST-1 uptake was measured by colorimetry. The error bars are SEM. * indicates significance at p < 0.05.

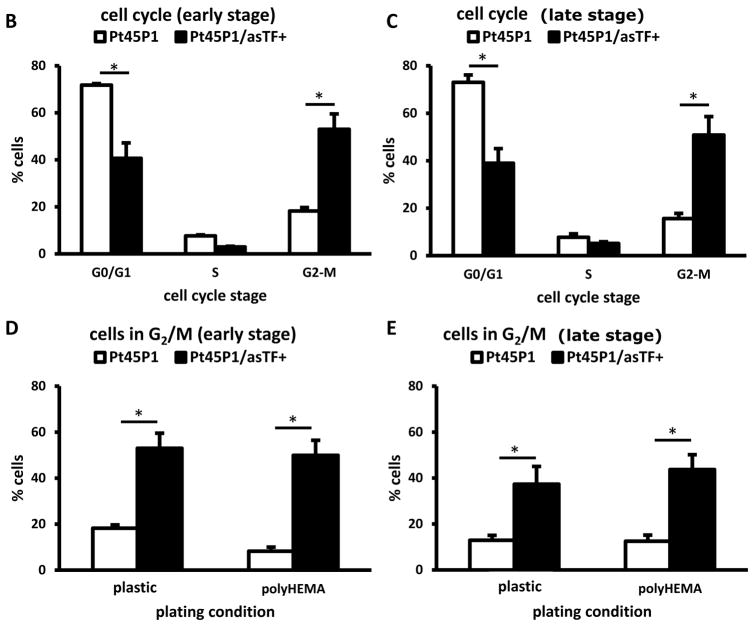

To further corroborate the proliferation results, we analyzed Pt45.P1 and Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells, plated under early- and late-stage conditions, for their distribution over cell cycle stages via propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. While Pt45.P1 cells had a significantly higher percentage of cells in the non-dividing G0/G1 phase, asTF-over-expressing cells were more prominently found in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle in both early (Figure 3A) and late-stage (Figure 3B) environments. Non-adherent survival and proliferation is an integral element of tumor progression, as it allows for the spread of the transformed cells. We therefore asked whether asTF over-expression contributes to cell cycle progression under non-adherent conditions. Pt45.P1 and Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells were plated either on conventional cell culture dishes, or on a layer of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (poly-HEMA) to prevent the cells from attaching to the plastic surface. A significantly higher percentage of cells over-expressing asTF resided in the dividing G2/M phase of the cell cycle under adherent and non-adherent conditions, in both conventional cell culture that is reflective of early stage tumors (Figure 3C) and in a late-stage-like environment (Figure 3D). Thus, asTF expression promotes cell growth under adhesive conditions that model cell attachment to the basement membrane, as well as in non-adhesive states that represent cancer cells in circulation.

Figure 3. Effect of asTF on cell cycle phases.

A) Flow cytometry profiles of PT45.P1 cells transfected with asTF or vector after staining with propidium iodide to analyze the phases of the cell cycle. The plating conditions are indicated above each graph. B,C) Pt45.P1 and Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells were plated in triplicates in early stage (B) or advanced stage (C) environments and were analyzed for cell cycle stage via flow cytometry after propidium iodide staining. The percentage of cells in G2/M was assessed after plating in conventional cell culture dishes (plastic) or on poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (poly-HEMA) to prevent cell adhesion. The comparison was done under early stage (D) or advanced stage (E) conditions. The error bars are SEM. * indicates significance at p < 0.05.

When CAIX was inhibited by U-104 in adherent cells under late-stage conditions, the percentage of Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells in the G0/G1 phase significantly increased by 44% as compared to Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells without drug treatment (Figure 4). This inhibition via U-104 also reduced the percentage of cells in the G2/M phase of the cells cycle in the late-stage-like environment, although the p-value only reached 0.07.

Figure 4. Decreased cell cycle progression under CAIX inhibition.

The effect of 75 μM U-104 on cell cycle progression was assessed by flow cytometry after propidium iodide staining. A) Flow cytometry profiles of PT45.P1 cells transfected with asTF or vector after staining with propidium iodide to analyze the phases of the cell cycle. The plating conditions are indicated above each graph. B,D) Percentage of cells in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle for Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells (B) and Pt45.P1 cells (D). C,E) Percentage of cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle for Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells (C) and Pt45.P1 cells (E). The error bars are SEM. * indicates significance at p < 0.05.

In a late-stage environment, CAIX acts as a mediator of asTF-imparted increase in cell motility

To measure the capacity for directed migration, a gap closure (“wound healing”) assay was performed, whereby we assessed the ability of asTF-over-expressing versus control Pt45.P1 cells to close a gap created by disrupting a monolayer through scratching the center of a well. asTF over-expression facilitated cell motility as evidenced by a complete restoration of the Pt45.P1/asTF+ monolayer within 24 hours, whereas Pt45.P1 cells still showed a visible gap after 48 hours (Figure 5A–C). To ensure that the migration result was not compromised by the different growth rates between Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells and the parental cell line Pt45.P1, we also performed the experiment in the presence of 2 μM thymidine, which blocks cell cycle progression at G1/S phase 26. The results were comparable, corroborating the enhancing effect of asTF on cell motility (Figure 5D–E).

Figure 5. Acceleration of gap closure by asTF over-expressors.

A) Comparison of gap closure ability of Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells versus Pt45P1 cells under early and advanced stage conditions. B,C) Quantification of cell motility. The graph shows the area unoccupied by Pt45.P1/asTF+ or Pt45.P1 cells under both early and advanced stages at various time intervals (0 h, 18 h, 24 h, 48 h). D,E) Effect of thymidine on cell motility. This assay was performed to compare the gap closure ability of asTF over-expressors and Pt45.P1 cells in the presence of thymidine (2 μM), a G1/S blocker. The graph represents the area unoccupied by Pt45.P1/asTF+ and Pt45.P1 cells under both normoxia and hypoxia at the designated time intervals. The error bars are SEM. *indicates significance at p < 0.05.

To evaluate the functional significance of CAIX, which acts downstream of asTF in pancreatic cancer, the cell migration assays were performed in the absence or presence of 75 μM U-104. Under late-stage conditions and in the presence of U-104, the ability of Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells to close the gap was significantly reduced as compared to untreated and/or DMSO treated cells (Figure 6). Of note, U-104 neither affected the motility of Pt45.P1 cells (in early- or late-stage environments), nor of Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells under early stage conditions (Figure 6G). Thus, the hypoxia-specific upregulation of CAIX by asTF-over-expressing cells imparts them with a more aggressive phenotype under conditions that represent late-stage tumors.

Figure 6. Effect of CAIX inhibition on gap closure.

A) Structure of the CAIX inhibitor U-104, 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-3-(4-sulfamoylphenyl)urea. B) Gap closure ability of Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells over 48 hours in the presence of the CAIX inhibitor U-104 (75 μM) or of vehicle control (0.15% DMSO) under advanced stage or early stage conditions. env. represents the environment, under which the cells were kept, with hyp indicating hypoxic/low glucose and norm indicating normoxic/high glucose. C–G) Quantification of the gap closure abilities by Pt45.P1 and Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells in the presence or absence of U-104. The unoccupied area at 0 hours is set to 100%. C) Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells in early or advanced environments without U-104 treatment. D) Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells in the presence of U-104 under early or late stage environments. E) Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells in the early stage environment in the presence of U-104 or vehicle control. F) Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells in the presence of U-104 or vehicle control under late stage environment. G) Pt45.P1 cells in the presence of U-104 under early or advanced environments. *indicates significance at p < 0.05.

asTF engages CAIX in vivo

To test the involvement of CAIX in asTF-fueled tumorigenesis in vivo, we implanted Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells orthotopically into the pancreata of nude mice. 8 weeks post-implantation, one group was treated with daily injections of U-104 for 4 weeks, whereas the control group received vehicle injections. The weights of the pancreata (surrogate readouts for tumor growth) in the treated group were lower than in the untreated group; however the p-value did not reach significance, possibly due to limited in vivo efficacy of U-104. (Figure 7A,B). When stained for Ki-67, a proliferation marker, the U-104-treated group did display significantly smaller levels of proliferating tumor cells as compared to the vehicle-treated group (Figure 7C,D). These results suggest that in vivo, asTF engages CAIX to promote tumor progression.

Figure 7. asTF in vivo.

A) Pancreata after extraction. Top row = mice treated with U-104, bottom row = untreated mice, left = sham injected mouse (no tumor). B) Mean and standard deviation of the pancreas weights from the groups of treated versus untreated mice. C) Percent positively staining cells from immunohistochemistry for Ki-67. D) Representative microscopic images of Ki-67 immunohistochemistry. Left = untreated mouse (injected with the vehicle), middle = mouse treated with U-104, right = negative control staining of a tumorous pancreas.

Discussion

In the hypoxic tumor environment of late-stage pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, asTF expression is prominent in tumor lesions, surrounding tumor tissues, and lymph nodes. It may correlate positively with tumor grade 11. Here we confirm that asTF supports proliferation and migration, thus enhancing aggressive tumor cell behavior. Although the in vitro phenotype of tumor growth and motility, induced by asTF over-expression, is comparable between the early-stage conditions and the late-stage conditions modeled here, the asTF-mediated functions in these different environments are associated with distinct downstream signaling pathways that do (hypoxia) or do not (normoxia) involve CAIX. asTF promotes the progression of pancreatic cancer in early- and late-stage environments alike. Physical interaction with β1 intergins is critical to asTF’s functions in a pancreatic cancer setting: to this effect, we recently published that asTF extensively co-localizes with β1-integrins in vivo in an orthotopic PDAC model employing Pt45.P1 cells 23. Since its initial discovery in the early 2000’s, asTF’s expression has been detected at significant levels in multiple PDAC cell lines and tumor growth promoting effects of free/secreted asTF have been described for several PDAC cell lines i.e. MiaPaCa-2, Capan-1, and Pt45.P111, 14, 15, 28; however, our paper is the first to assess the intracellular mechanisms underlying asTF’s effects on PDAC cells under patently hypoxic conditions. Whereas many cell functions decline in hypoxia/high lactate, asTF maintains its activity by engaging a CAIX-associated pathway that physiologically is an element of the cellular hypoxia response

Because glycolysis constitutes a common metabolic pathway in cancer cells that leads to the generation and accumulation of high levels of lactic acid, the intracellular pH of these cells drops substantially. CAIX is a membrane-bound enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of water and carbon dioxide, extracellularly, to bicarbonate ions and protons. These bicarbonate ions are then transported inside the cells, elevating the intracellular pH toward physiologic levels, so that cell survival is assured. Through the same process, CAIX leads to an accumulation of protons extracellularly, which makes the extra-cellular environment more acidic. In various types of cancers, patients having tumors with high CAIX expression have a higher risk of locoregional failure, disease progression, and higher risk to develop metastases 29. CAIX is a downstream mediator of HIF-1α, which is activated by hypoxia. By contrast, HIF-2α expression is seen in Pt45.P1 cells, and is not associated with asTF levels. This difference in the expression levels of hypoxia-inducible factors is important for cell fate because HIF-1α and HIF-2α regulate distinct hypoxia-associated pathways 30. asTF may engage various signaling pathways in transformed cells . One or more of these mechanisms may be associated with the environment-dependent, alternative pathways described here (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Signaling pathways associated with asTF.

Schematic representation of two distinct pathways to increased proliferation and motility, which are induced by asTF. Under normoxic, early stage conditions the tumor promoting effects by asTF are exerted independently of CAIX. In the hypoxic, advanced stage tumor environment, the selective up-regulation of CAIX ensures that proliferative and motile potential are sustained.

U-104 has been used in the pharmacological inhibition of CAIX, both in vitro and in vivo. A benzenesulphonamide, U-104, specifically inhibits CAIX and CAXII, whereas it has only a weak inhibitory effect on other carbonic anhydrases. CAIX inhibition via U-104 may significantly decrease tumor growth in breast cancer 25,24. In our in vitro model of late-stage tumors, we did see a significant reduction in pancreatic cancer cell growth and migration in the presence of U-104, which was limited to Pt45.P1/asTF+ cells expressing high levels of CAIX, while Pt45.P1 cells in the same environment express low levels of CAIX and were not affected by U-104.

For over six decades, cancer cells have been grown in culture 31 and the conditions have conventionally been devised to maximize cell growth. However, such systems disregard one of the important pathophysiological properties of late-stage tumors: the prevalence of hypoxia 32. During early stages of transformation, tumor cells acquire gain-of-function mutations in oncogenes or loss-of-function mutations in tumor suppressor genes that cause excessive proliferation and anti-apoptosis. As the transformed cells multiply, they outgrow the diffusion limits of oxygen, thus, becoming hypoxic. Because of increased glycolysis, more lactic acid is generated, which makes the lesions acidic 33, 34. Even though new blood vessels are formed in cancer angiogenesis, they are disorganized and cannot effectively alleviate this state 34, 35, 36. Such conditions need to be studied in model systems that account for the microenvironment that is prevalent during tumor progression.

While cell culture is indispensable for cancer research, it has important limitations for modeling in situ environments. The technique has been developed in a direction that allows high signal-to-noise ratios, which often egregiously exceed bona fide physiologic changes. Plastic dishes render cells hypo-active, so that their transcriptional baseline activity is reduced compared to cell growth on extracellular matrix molecules, and ensuing responses to external stimuli may be exaggerated 37. Likely in part because of the culture conditions, gene expression changes by cell lines in response to environmental stimuli have disproportionately higher magnitude than similar changes occurring in vivo38. We therefore sought to study asTF pathobiology under conditions reaching beyond the canonical normoxic, high glucose cell culture conditions that maximize cell division and produce supra-physiologic responses. An aggressive phenotype that may arise in a late-stage tumor micro-environment prompted us to study the mechanisms that promote aggressive behavior under hypoxic, low-glucose, high-lactate tumor conditions, revealing a heretofore unknown asTF-CAIX axis in pancreatic cancer. We note the importance of adapting experimental models as closely as possible to the disease states under study.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by DOD Grant PR094070 to GFW and NIH/NCI Grant 1R21CA16029301-A1 and 1R01CA190717-A0 to VYB. The cell line Pt45P1 was generously provided by Prof. Holger Kalthoff, UKSH, Campus Kiel, Germany.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Zhang G, He B, Weber GF. Growth factor signaling induces metastasis genes in transformed cells: molecular connection between Akt kinase and osteopontin in breast cancer. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6507–19. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6507-6519.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rickles FR, Shoji M, Abe K. The role of the hemostatic system in tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis: tissue factor is a bifunctional molecule capable of inducing both fibrin deposition and angiogenesis in cancer. Int J Hematol. 2001;73:145–50. doi: 10.1007/BF02981930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wojtukiewicz MZ, Sierko E, Klement P, Rak J. The hemostatic system and angiogenesis in malignancy. Neoplasia. 2001;3:371–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falanga A, Marchetti M, Vignoli A. Coagulation and cancer: biological and clinical aspects. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:223–33. doi: 10.1111/jth.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falanga A, Marchetti M, Vignoli A, Balducci D. Clotting mechanisms and cancer: implications in thrombus formation and tumor progression. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2003;1:673–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wojtukiewicz MZ, Sierko E, Kisiel W. The role of hemostatic system inhibitors in malignancy. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2007;33:621–42. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palumbo JS, Kombrinck KW, Drew AF, Grimes TS, Kiser JH, Degen JL, Bugge TH. Fibrinogen is an important determinant of the metastatic potential of circulating tumor cells. Blood. 2000;96:3302–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lal I, Dittus K, Holmes CE. Platelets, coagulation and fibrinolysis in breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:207. doi: 10.1186/bcr3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palumbo JS. Mechanisms linking tumor cell-associated procoagulant function to tumor dissemination. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2008;34:154–60. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1079255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogdanov VY, Balasubramanian V, Hathcock J, Vele O, Lieb M, Nemerson Y. Alternatively spliced human tissue factor: a circulating, soluble, thrombogenic protein. Nat Med. 2003;9:458–62. doi: 10.1038/nm841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unruh D, Turner K, Srinivasan R, Kocatürk B, Qi X, Chu Z, Aronow B, Plas DR, Gallo CA, Kalthoff H, Kirchhofer D, Ruf W, et al. Alternatively spliced tissue factor contributes to tumor spread and activation of coagulation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:9–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keely S, Glover LE, MacManus CF, Campbell EL, Scully MM, Furuta GT, Colgan SP. Selective induction of integrin beta1 by hypoxia-inducible factor: implications for wound healing. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2009;23:1338–46. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-125344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van den Berg YW, van den Hengel LG, Myers HR, Ayachi O, Jordanova E, Ruf W, Spek CA, Reitsma PH, Bogdanov VY, Versteeg HH. Alternatively spliced tissue factor induces angiogenesis through integrin ligation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19497–502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905325106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hobbs JE, Zakarija A, Cundiff DL, Doll JA, Hymen E, Cornwell M, Crawford SE, Liu N, Signaevsky M, Soff GA. Alternatively spliced human tissue factor promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a pancreatic cancer tumor model. Thromb Res. 2007;120:S13–21. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(07)70126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Signaevsky M, Hobbs J, Doll J, Liu N, Soff GA. Role of alternatively spliced tissue factor in pancreatic cancer growth and angiogenesis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2008;34:161–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1079256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Dong M, Sheng W, Huang L. Roles of Carbonic Anhydrase IX in Development of Pancreatic Cancer. Pathology & Oncology Research. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12253-015-9935-6. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wykoff CC, Beasley NJ, Watson PH, Turner KJ, Pastorek J, Sibtain A, Wilson GD, Turley H, Talks KL, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, et al. Hypoxia-inducible expression of tumor-associated carbonic anhydrases. Cancer research. 2000;60:7075–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sipos B, Möser S, Kalthoff H, Török V, Löhr M, Klöppel G. A comprehensive characterization of pancreatic ductal carcinoma cell lines: towards the establishment of an in vitro research platform. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:444–52. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0784-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srinivasan R, Ozhegov E, van den Berg YW, Aronow BJ, Franco RS, Palascak MB, Fallon JT, Ruf W, Versteeg HH, Bogdanov VY. Splice variants of tissue factor promote monocyte-endothelial interactions by triggering the expression of cell adhesion molecules via integrin-mediated signaling. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:2087–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuroda Y, Wakao S, Kitada M, Murakami T, Nojima M, Dezawa M. Isolation, culture and evaluation of multilineage-differentiating stress-enduring (Muse) cells. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1391–415. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi Z, Mirza M, Wang B, Kennedy M, Weber G. Osteopontin-a alters glucose homeostasis in anchorage-independent breast cancer cells. Cancer letters. 2014;344:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adler B, Weber GF, Cantor H. Activation of T cells by superantigen: cytokine production but not apoptosis depends on MEK-1 activity. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3749–54. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199811)28:11<3749::AID-IMMU3749>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unruh D, Unlu B, Lewis CS, Qi X, Chu Z, Sturm R, Keil R, Ahmad SA, Sovershaev T, Adam M, Van Dreden P, Woodhams BJ, et al. Antibody-based targeting of alternatively spliced tissue factor: a new approach to impede the primary growth and spread of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lou Y, McDonald PC, Oloumi A, Chia S, Ostlund C, Ahmadi A, Kyle A, Auf dem Keller U, Leung S, Huntsman D, Clarke B, Sutherland BW, et al. Targeting tumor hypoxia: suppression of breast tumor growth and metastasis by novel carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3364–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lock FE, McDonald PC, Lou Y, Serrano I, Chafe SC, Ostlund C, Aparicio S, Winum JY, Supuran CT, Dedhar S. Targeting carbonic anhydrase IX depletes breast cancer stem cells within the hypoxic niche. Oncogene. 2013;32:5210–9. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosner M, Schipany K, Hengstschläger M. Merging high-quality biochemical fractionation with a refined flow cytometry approach to monitor nucleocytoplasmic protein expression throughout the unperturbed mammalian cell cycle. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:602–26. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kocatürk B, Berg YW, Tieken C, Mieog SJD, Kruijf EM, Engels CC, Ent MA, Kuppen PJ, Velde CJ, Ruf W. Alternatively spliced tissue factor promotes breast cancer growth in a 1 integrin-dependent manner. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:11517–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307100110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haas SL, Jesnowski R, Steiner M, Hummel F, Ringel J, Burstein C, Nizze H, Liebe S, Lohr JM. Expression of tissue factor in pancreatic adenocarcinoma is associated with activation of coagulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4843–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i30.4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Kuijk SJ, Yaromina A, Houben R, Niemans R, Lambin P, Dubois LJ. Prognostic Significance of Carbonic Anhydrase IX Expression in Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol. 2016;6:69. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ratcliffe PJ. HIF-1 and HIF-2: working alone or together in hypoxia? J Clin Invest. 2007;117:862–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI31750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gey G, Coffman W, Kubicek M. Tissue culture studies of the proliferative capacity of cervical carcinoma and normal epithelium. Cancer Res. 1952;12:264–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaupel P, Mayer A. Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2007;26:225–39. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osinsky S, Zavelevich M, Vaupel P. Tumor hypoxia and malignant progression. Exp Oncol. 2009;31:80–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayer A, Vaupel P. Hypoxia, lactate accumulation, and acidosis: siblings or accomplices driving tumor progression and resistance to therapy? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;789:203–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7411-1_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carmeliet P, Jain R. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–57. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gatenby R, Smallbone K, Maini P, Rose F, Averill J, Nagle R, Worrall L, Gillies R. Cellular adaptations to hypoxia and acidosis during somatic evolution of breast cancer. British journal of cancer. 2007;97:646–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Syed M, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Skau KA, Weber GF. Acetylcholinesterase supports anchorage independence in colon cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:787–98. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weber GF, Johnson BN, Yamamoto BK, Gudelsky GA. Effects of stress and MDMA on hippocampal gene expression. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:141396. doi: 10.1155/2014/141396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]