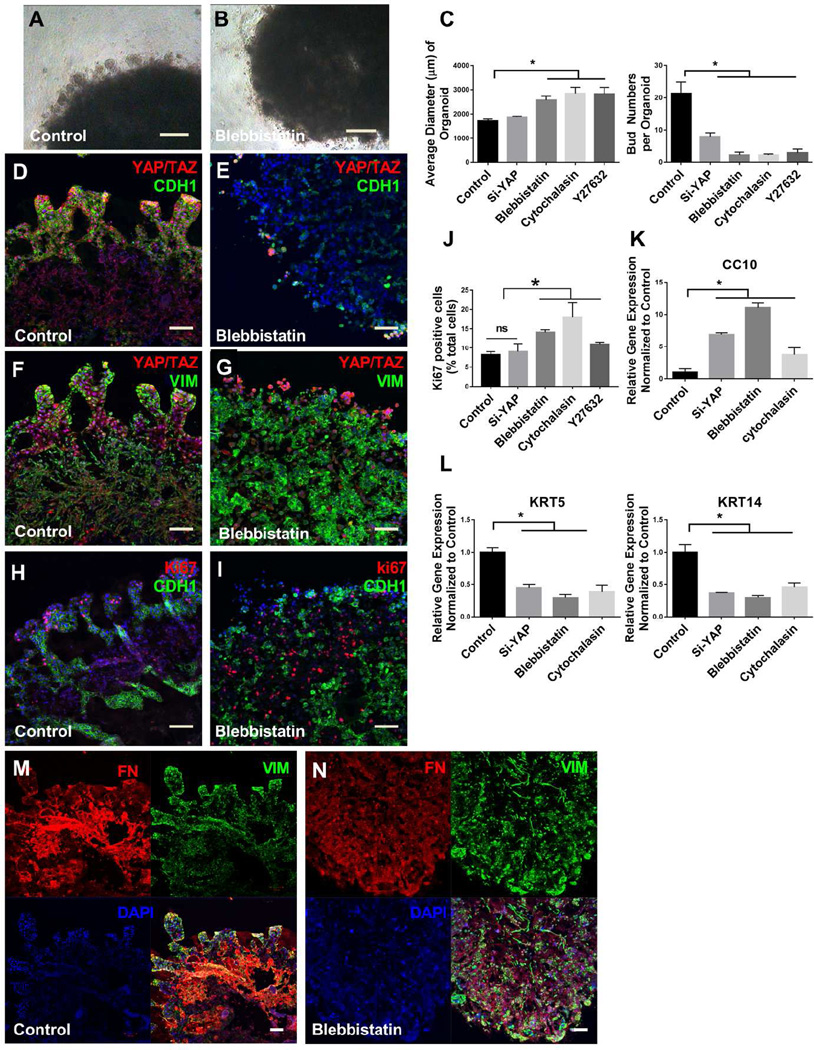

Figure 5.

Invasive tubular structures require localized YAP and actomyosin. Tubular outgrowths from airway organoids invade surrounding matrix shown in the control (A), loss of such structures with blebbistatin treatment (B). Quantification the number of invasive tubular structures (number of buds) and the average diameter of airway organoids in different treatment groups comparing with control (C). Co-staining of YAP/TAZ (red) and E-cadherin (CDH1, green) reveals high expressing YAP/TAZ cells within invasive epithelial tubular structures of airway organoids in the control (D) and their relative loss and disorganization in blebbistatin treatment group (E). Co-staining of YAP/TAZ (red) and Vimentin (green) in the control (F) and blebbistatin treatment group (G). Co-staining of Ki67 (red) and Vimentin (green) in the control (H) and blebbistatin treatment group (I), along with quantification of Ki67 postitive cells (J). Co-staining of Fibronectin (red) and Vimentin (green) in the control (M) and blebbistatin treatment group (N). Relative gene expression of KRT5, KRT14 and CC10 in airway organoids with and without Si-YAP, blebbistatin and cytochalasin D treatment (K, L). Values in graphs represent mean ± SEM; n=3, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; t-test. Scale bars, 200µm (A–B), 100µm (D, E, F, G, H, I, M, N).