Abstract

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is an unusual salivary gland malignancy that remains poorly understood. It is a slow growing but aggressive neoplasm with a tendency for recurrence. It is characterized by the proliferation of ductal (luminal) and myoepithelial cells in cribriform, tubular, solid, and cystic forms. Standard treatment, including surgery with postoperative radiation therapy, has attained reasonable local control rates, but distant metastases do not allow any improvement in the survival rate. The understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving ACC is quite rudimentary. We present a case of a 55-year-old female diagnosed with ACC involving the floor of the mouth with an aim to present the carcinoma's behavior, immunohistocytochemistry, the staining pattern, its treatment, and prognosis.

Keywords: Adenoid cystic carcinoma, Minor salivary gland, Floor of the mouth, Malignant

1. Introduction

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is the fourth most common malignant epithelial salivary gland neoplasm, accounting for approximately 10% of all salivary carcinomas.1 ACC was first described by three Frenchmen (Robin, Lorain, and Laboulbene) in the years 1853 and 1854. It was later described as cylindroma by Billroth2 in 1856. The term ‘adenoid cystic carcinoma’ was coined in the year 1928 by Spies3 and is in use till date. ACC constitutes less than 1% of all head and neck malignancies with 50% occurring intraorally, commonly in the hard palate.3, 4 Other less frequent intraoral sites are the lower lip, retromolar region, sublingual gland, buccal mucosa, and floor of the mouth.3 Extraorally, parotid gland (25%) is the single most common site of origin. These are clinically innocuous lesions usually characterized by small size and slow growth,4 but are generally associated with extensive subclinical invasion and distant metastasis.4 Pain is an important symptom of the condition due to its perineural spread.3 It occurs mostly in 5th and 6th decades, with a female predilection. Cervical lymph node metastasis is found in 8–13% of cases. Distant metastasis is found in up to 50% cases in lungs and bones. ACCs involving minor salivary glands have worse prognosis than those of the major salivary glands.3

2. Case report

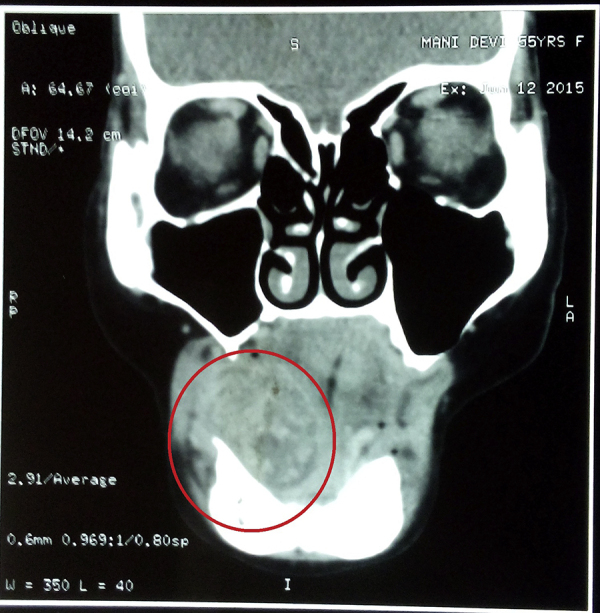

A 55-year-old female patient reported to our unit with a chief complaint of intraoral swelling below the tongue for the last one year. She was apparently asymptomatic one-year back when she noticed a small swelling over the right side of the floor of the mouth. The swelling gradually increased in size over this period. No associated pain, bleeding, or discharge was found. Past medical and dental history was not significant. Extraoral examination revealed a firm, diffuse, nontender swelling with slight fullness of the right side cheek and lower lip region. Intraorally, a firm, diffuse, nontender oval-shaped swelling measuring approximately 3 cm × 4 cm was present in the right side of floor of mouth region extending over the edentulous alveolar ridge and displacing the tongue contra laterally (Fig. 1). The tip of tongue deviated toward the right side on protrusion. No loss of taste and general sensation of the tongue were noted. An ulcer was noticed to develop over the swelling following the FNAC from the puncture site. Cervical lymph nodes were not palpable. Routine hematological findings were within normal limits. Computed tomographic scan (coronal view) showed an ill-defined homogenous poorly capsulated mass present in the right floor of the mouth region with infiltration in the adjacent musculature of tongue (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative intraoral photograph showing the swelling over the floor of the mouth.

Fig. 2.

Computed tomographic scan (coronal view) shows an ill-defined homogenous poorly capsulated mass present in the right floor of the mouth region with infiltration in the adjacent musculature of tongue.

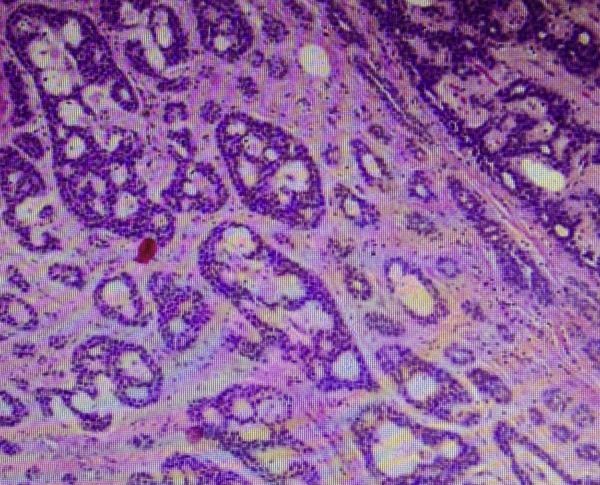

Fine-needle aspiration cytology was suggestive of ACC of the minor salivary gland. TNM staging was T3N0M0. The treatment plan was complete excision of the lesion through intraoral approach under general anesthesia. A longitudinal incision of approximately 4 cm length was placed over the most prominent region of swelling, and then layer-wise dissection was done. On exposure, the tumor was found capsulated and hence complete en bloc excision was done (Fig. 3). Lingual nerve and deep lingual vessels were preserved. The closure was done in layers with 3-0 vicryl suture. After one week, wound healing was found satisfactory. Histopathology study revealed it as ACC of the minor salivary gland (Fig. 4). The patient was advised postoperative radiotherapy. She underwent radiotherapy with 60 Gy Cobalt. Following radiotherapy, oral mucositis was observed, which was managed symptomatically. Patient was advised for regular follow-up visits after every three months and no locoregional recurrence has been found as yet (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Excised lesion.

Fig. 4.

Photomicrograph (H & E stained) revealed numerous duct-like structures and tubules containing mucinous substance; ducts were lined by cuboidal epithelium. Various islands of hyperchromatic, basophilic, and isomorphic cells surrounded by hyalinized stroma were seen.

Fig. 5.

Postoperative photograph showing satisfactory wound healing.

3. Discussion

ACC accounts for approximately 10% of all salivary gland neoplasms. The parotid gland is the single most common site of origin (25%) in the head and neck regions. Most ACCs arise in the minor salivary glands (60%). ACC of minor salivary gland origin occurs most frequently in the hard palate.4 Foote and Frazell5 were the first to describe that ACC was located in the major and minor salivary glands. They also reported that the tumors were usually small with an incomplete capsule and showed the variations in histology that had a propensity to perineural spread. They suggested that relatively conservative surgical approach leads to high failure rates and advocated a more radical surgical treatment. At present, ACC remains an extremely difficult lesion to treat. Conley and Dingman6 described it as one of the most biologically destructive and unpredictable tumors of the head and neck. It has high recurrence rate in patients with increased survival and even when radical excision has been performed.

Clinically, ACC is a relentless, slow growing, and progressive tumor. Sometimes it is associated with pain in cases of large tumor size and perineural spread.4 There is a strong positive correlation between site of origin and prognosis. The more favorable prognosis with major salivary gland ACC as compared to minor salivary gland is attributed to the earlier diagnosis of the neoplasm due to increased accessibility.3 ACC of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses has got worse prognosis than in any other area of the head and neck regions.7

Tumor staging is considered as one of the most reliable indicators of overall prognosis, but some authors have emphasized the importance of histological subtyping.8 Szanto et al.9 introduced histopathological grading as cribriform or tubular (grade I), less than 30% solid (grade II), or greater than 30% solid (grade III). The cribriform variant demonstrates significantly poor prognosis in terms of local recurrence rate. Solid histologic pattern of ACC appeared to have an overall worse prognosis in terms of distant metastases and long-term survival. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy is widely accepted as the diagnostic procedure of head and neck lesions. The cytologic typing of ACC is helpful in most cases by the finding of large globules of extracellular matrix, partially surrounded by basaloid tumor cells, but lacking characteristic globules.10 Imaging includes ultrasonography in case of major salivary glands. CT is indicated if invasion of adjacent structures is suspected. MRI is helpful in cases of perineural invasion or skull base invasion.6

The use of immunohistocytochemistry, and the staining pattern of p53, bcl-2, P-glycoprotein, glutathione S transferase, and topoisomerase, and sequencing analysis of p53, due to their proven association with poor prognosis and therapy resistance, have been analyzed. p53 alteration is an independent prognostic marker and the proteins known for their radio- and chemotherapy resistance can be overexpressed in some ACCs, suggesting that those molecules could influence the outcome of new therapeutic management.11 ACC shows aggressive behavior by its ability to invade and metastasize. One more factor regulating these functions is the urokinase-type plasminogen activator and its receptor. The urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor participates not only in several normal cellular processes but also influences tumor invasion and metastasis by facilitating the destruction of extracellular matrices. Studies on skull base ACC urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor expression proved it to be a negative prognostic factor.12

The minor salivary gland tumors should be treated by local radical excision and postoperative radiotherapy.13 ACCs arising in major salivary glands are treated surgically, followed by possible addition of adjunctive radiotherapy. ACC of the parotid gland should be treated by preservation of the facial nerve if not paralyzed preoperatively and not involved by tumors at the time of surgery, followed by postoperative radiotherapy.14 Submandibular gland ACC should be treated by a supraomohyoid neck dissection followed by postoperative radiotherapy. Selective neck dissection for other involving sites is controversial in N0 patients.15

In patients who receive postoperative radiation therapy, improved outcomes have been observed with radical surgery. Radiation, usually in doses of 60 Gy or more, may be of benefit when there is minimal residual microscopic disease. On few occasions there is frequently unrecognized perineural invasion in specimens with “negative” margins that would have benefited from the addition of radiation therapy.16 The use of fast neutron irradiation seems to be better than photon beam therapy because of the higher relative biologic effectiveness of neutron radiation.17 Chemotherapy currently is seeking a role in the management of advanced and metastatic salivary gland tumors.18

ACCs arising from sites close to the cranial base (nasopharynx, nasal cavity, and maxilla) have a significantly increased risk of local recurrence. This is related to the difficulty of obtaining a clear resection margin at the cranial base because of the difficulties associated with the surgery, intracranial extension of the tumor along nerves, and restrictions on the limits of resection due to the proximity of neural and vascular structures. Gamma knife has been recommended for the treatment of recurrent salivary gland tumors involving the skull base, using a dose of 15 Gy. Grade I tumors have also been associated with early recurrence (>1 year) and an earlier risk for development of distant metastases.19

Metastatic spread to regional lymph nodes is rare, but distant metastasis to the lungs and bones is frequent. 5-year survival rates are considerably high, but 10- to 20-year survival rates are very low.20 Median survival times after appearance of distant metastases among patients with isolated lung metastases and those with bone metastases with or without lung involvement were 54 and 21 months, respectively. The larger size of tumor at presentation and the development of locoregional treatment failure are the two factors most predictive of distant metastases.21 Thoracotomy to excise solitary salivary malignant lung metastases may be worthwhile when the salivary histology is low grade and the disease-free interval from treatment of the primary and detection of the metastasis is measured in years. There are advocates for lung resection of ACC metastases who report good-quality survival, with an estimated 5-year survival rate of 84%, which continued to decline until there were no survivors after 14 years. Routine chest radiographs on follow-up may help in early recognition of the lung metastasis.22, 23, 24

4. Conclusion

ACC follows an unpredictable course, and shows locally aggressive behavior, high rate of recurrence in case of perineural invasion, and an uncertain prognosis after surgical resection. Postoperative radiotherapy is advocated when disease-free margins cannot be obtained surgically and when there is locally advanced disease or high-grade histological findings. Long-term follow-up is advised because local recurrence and distant metastasis may occur late in the course of disease.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Kim K.H., Sung M.W., Chung P.S., Rhee C.S., Park C.I., Kim W.H. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120:721–727. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1994.01880310027006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Germany B.T., Riemer G. 1856. The Cylindroma Studies on the Development of the Blood Vessels Along with Observations from the Royal University Surgical Clinic Berlin; pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giannini P.J., Shetty K.V., Horan S.L., Reid W.D., Litchmore L.L. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the buccal vestibule: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:1029. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahajan A., Kulkarni M., Parekh M., Khan M., Shah A., Gabhane M. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of hard palate: a case report. Oral Maxillofac Pathol J. 2011;2:127. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foote F.W., Frazell E.L. Tumours of the major salivary glands. Cancer. 1953;6:1065–1133. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195311)6:6<1065::aid-cncr2820060602>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conley J., Dingman D.L. Adenoid cystic carcinoma in the head and neck (cylindroma) Arch Otolaryngol. 1974;100:81–90. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1974.00780040087001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard D.J., Lund V.J. Reflections on the management of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93:338–341. doi: 10.1177/019459988509300309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiro R.H., Huvos A.G. Stage means more than grade in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1992;164:623–628. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80721-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szanto P.A., Luna M.A., Tortoledo M.E. Histologic grading of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands. Cancer. 1984;54:1062–1069. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840915)54:6<1062::aid-cncr2820540622>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagel H., Hotze H.J., Laskawi R. Cytologic diagnosis of adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary glands. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;20:358–366. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199906)20:6<358::aid-dc6>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolude B., Adisa A.O., Lawal A.O., Adeyemi B.F. Strong immunohistochemical expression of C-kit may characterize adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary gland. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2014;26(4):549–553. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doerr T.D., Marentette L.J., Flint A. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor expression in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skull base. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:215–218. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradley P.J. Submandibular gland and the minor salivary gland neoplasms. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;7:72–78. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castler J.D., Conley J.J. Surgical management of adenoid cystic carcinoma in the parotid gland. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;106:332–338. doi: 10.1177/019459989210600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medina J.E. Neck dissection in the treatment of cancer of major salivary glands. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 1998;31(5):815–822. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umeda M., Nishimatsu N., Yokoo S. The role of radiotherapy for patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma. Oral Med Oral Surg Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:724–729. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.106302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber P.E., Debus J., Latz D. Radiotherapy for advanced adenoid cystic carcinoma: neutrons, photons or mixed beam? Radiother Oncol. 2001;59:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(00)00273-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spiro R.H. Management of malignant tumours of the salivary glands. Oncology. 1998;12:671–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee N., Millender L.E., Larson D.A. Gamma knife radiosurgery for recurrent salivary gland malignancies involving the base of skull. Head Neck. 2003;25:210–216. doi: 10.1002/hed.10193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westra W.H. The surgical pathology of salivary gland neoplasms. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 1999;39:919–943. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley P.J. Distant metastases from salivary glands. Cancer ORL. 2001;63:233–242. doi: 10.1159/000055748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sung M.-W., Kim K.H., Kim J.-W. Clinicopathologic predictors and impact of distant metastasis from adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:1193–1197. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.11.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acharya S., Annehosur V., Hallikeri K., Shivappa S.K. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the sublingual salivary gland: case report of a rare clinical entity. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2015 Available online 15 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coca-Pelaz A., Rodrigo J.P., Bradley P.J. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck – an update. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(7):652–661. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]