Curing of the patient, prolonging of life, and avoiding premature death should be the primary focus of the cancer care team in the care of the patient. Fortunately, with advances in clinical trials and biomedical care, we now see that patients are cured or living longer. Cancer, once considered an acute disease with a diagnosis being synonymous with death, pain and suffering is now viewed more as a chronic illness with the extension of life as the real goal. It is also reasonable to say that with advances in radiation therapy, refinements in chemotherapeutic agents, personalized medicine coupled with aggressive surgeries, outcomes for cure as well as extension of life are increasingly attainable.

With an extension of life and survivorship being more within our grasp, patient care goals are expanding beyond active biomedical treatment to include the maintenance and improvement of function, relief of suffering, and improvement of the quality of life. When prolonging life is not possible, health care is charged with facilitating a good death through the advances in psychosocial and palliative care.

Advances in research, coupled with the growth and development of multidisciplinary specializations requires all professionals to take the view that whole patient care is an essential component of comprehensive care of the patient.[1] Research has demonstrated the very high prevalence rates of cancer-related distress experienced by the patient. Studies in Canada and the United States report that high levels of distress (broadly defined) affects 35-45% of cancer patients from time of diagnosis, through treatment, recurrent disease, palliative care, and survivorship.[2,3] When describing distress, we are no longer talking only about anxiety or depression. In fact, large research studies have demonstrated that distress is complex and may be exacerbated by physical, psychosocial, spiritual, and/or practical concerns.[4] The interrelationship of these dimensions contribute to the patient experience, their quality of life, and how they cope with cancer and its treatment.

Given the prevalence rates of distress, how are health care programs and how are we as health care professionals identifying and addressing patient distress? First, research has already demonstrated that patients under-report concerns when asked how they are doing.[5] Unfortunately the casual “how are you doing” question is seen more as a salutation than a clinical inquiry. If the question is seen as a salutation, as it often is, it is unlikely that the patient will respond identifying key concerns. As well, research has demonstrated that health care providers rely mostly on clinical acumen and not standardized measures to determine patient's key concerns or symptoms of stress. In fact, less than 15% of providers actually use standardized questionnaires to assess how patients are managing their illness.[6,7] Given these findings, it is not surprising to see high error rates in assessing how patients are doing, something that we would find unacceptable in physical medicine.[8,9]

As trained cancer care providers, it is incumbent on us to reflect the values promoted by Hippocrates (460-378 BCE). Subsequently, it follows that as health care professionals, we must promote the values of best practice in patient care by striving to do no harm, to do medical good, and to commit to scientific objectivity. One way we can accomplish this level of care is by embracing the scientist-practitioner model of patient care in our respective disciplines. Whatever discipline we represent, the primary driver of patient care should be based on objective measurement.[10]

Vital signs of body temperature, pulse or heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate are the four physical vital signs that are routinely measured to best describe a patient's physical status. Because of the high prevalence rates of pain in oncology care, pain has been designated the 5th vital sign.[11] Similarly, because of the high prevalence rate of distress present in cancer patients, distress has been designated the 6th vital sign.[12,13,14]

This labeling of Distress as the 6th Vital Sign and the adoption of routine screening has been accepted in many countries. The clinical application of standardized screening for distress is increasingly being applied and incorporated into routine cancer care practice.

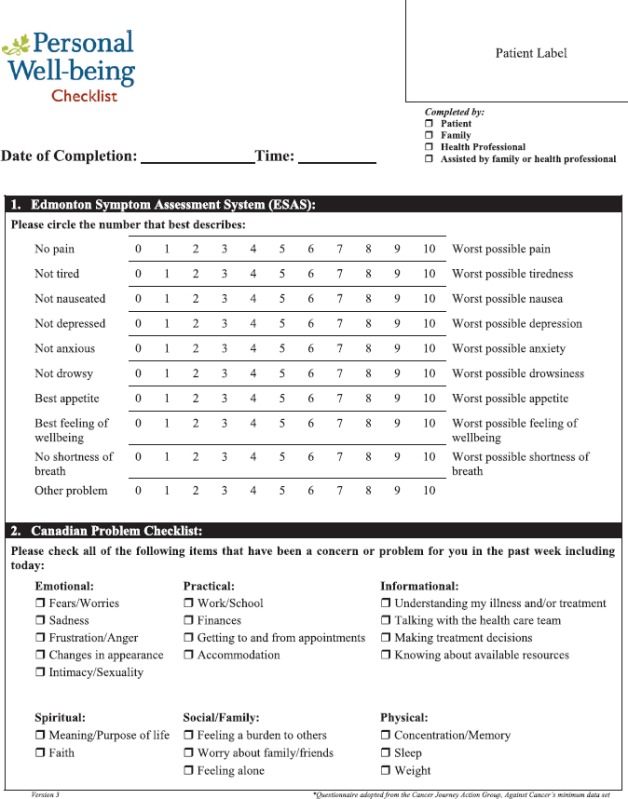

There are several standardized screening measures that are in use. One of the first such short tools with good sensitivity is the Distress Thermometer and the Problem Check List.[4] Another, the Personal Well-Being Check List, with good sensitivity and specificity, widely used across Canada, is a short tool designed to ask patients to self-rate key concerns in a Likert format.(insert Personal Well-being Checklist here).

Screening is a snapshot of patient's key concerns which should be used to guide the health care team to conduct further assessments and pursue appropriate referrals if required. In looking at the ESAS part of the Personal Well-being Checklist, scores of 7 and above are considered in the very high range requiring immediate action by the health care team. Items scored in the 4-7 range are considered moderately high, and require further discussion about the identified concern. It is essential to be mindful that screening for distress alone will not result in a change; follow-up is the essential next step.

To be effective, Screening for Distress must be seen as a clinical tool that creates an opportunity for the nurse and health care team to address key concerns of the patient. Screening can guide the conversation and facilitate a symptom management plan. From our work, we have learned that Screening for Distress is about teamwork. Screening for Distress results in a more accurate identification of key symptom concerns that will transcend “guess work” about how the patient is doing. These concerns can be resolved in the clinic or if necessary, by a referral to an appropriate professional. Screening for Distress, when implemented into clinic practice, can create efficiencies, and significantly decrease the burden to the patient, family, and healthcare system.

Since Screening for Distress has been branded as the 6th vital sign in oncology, there has been a significant increase in research and publications on the screening, assessment and management of multifactorial distress. As well several cancer care delivery programs have included distress screening and distress management as a new accreditation standard.[15,16,17]

Given the prevalence of distress, and our ability to understand and manage the symptoms of distress, it seems that this is the right time to embrace the “science of caring” in our clinical practice. By implementing programs of Screening for Distress as the 6th vital sign, using standardized measures, we address cancer care for the “whole patient” as scientist-practitioners. In observing that distress as the 6th vital sign is emerging as an international symbol for improving psychosocial care, Dr. Eduardo Cazap, UICC President stated: “We expect that recognizing distress as the 6th vital sign will improve the treatment of cancer patients, improve outcomes for cancer patients, and improve the effectiveness of cancer care systems around the world.”[18]

Acknowledgments

This article was written on the basis of a presentation given at the AONS 2015 conference held in Seoul Korea by the Asian Oncology Nursing Society.

References

- 1.Adler NE, Page A. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting, National Institute of Medicine (US) and Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, Goodey E, Koopmans J, Lamont L, et al. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2297–304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCCN practice guidelines for the management of psychosocial distress. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Oncology (Williston Park) 1999;13:113–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Homsi J, Walsh D, Rivera N, Rybicki LA, Nelson KA, Legrand SB, et al. Symptom evaluation in palliative medicine: Patient report vs systematic assessment. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:444–53. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pirl WF, Muriel A, Hwang V, Kornblith A, Greer J, Donelan K, et al. Screening for psychosocial distress: A national survey of oncologists. J Support Oncol. 2007;5:499–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell AJ. Pooled results from 38 analyses of the accuracy of distress thermometer and other ultra-short methods of detecting cancer-related mood disorders. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4670–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Jenkins V, Saul J. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1011–5. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell AJ, Hussain N, Grainger L, Symonds P. Identification of patient-reported distress by clinical nurse specialists in routine oncology practice: A multicentre UK study. Psychooncology. 2011;20:1076–83. doi: 10.1002/pon.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMurtry R, Bultz BD. Public policy, human consequences: The gap between biomedicine and psychosocial reality. Psychooncology. 2005;14:697–703. doi: 10.1002/pon.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Pharmaceutical Council. Pain: Current Understanding of Assessment, Management and Treatments. National Pharmaceutical Council, USA. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bultz BD, Carlson LE. Emotional distress: The sixth vital sign in cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6440–1. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland JC, Bultz BD. National comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). The NCCN guideline for distress management: A case for making distress the sixth vital sign. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rebalance Focus Action Group. A position paper: Screening key indicators in cancer patients: Pain as a 5th vital sign and emotional distress as a 6 th vital sign. Can Strategy for Cancer Control Bull. 2005;7 Supplement:4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.A ccreditation Canada. Cancer Care and Oncology Services Standards. 2008. http://www.accreditation.ca/accreditationprograms/qmentum/standards/cancercare/

- 16.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer, 2012. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. 2012. [Last accessed on 2015 Aug 31]. Available from: https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.ashx .

- 17.Fang CK. Taiwan, written communication. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulz B, Loscalzo MJ, Holland JC. Distress as the 6th vital sign is emerging as an international symbol for improving psychosocial care. In: Holland JC, Breitbart WS, Jacobsen PB, Lederberg MS, Loscalzo MJ, McCorkle RS, editors. Psycho-Oncology. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. pp. 735–8. [Google Scholar]