Abstract

Introduction

Abdominal tuberculosis (TB) has always been a diagnostic challenge, even for the astute surgeon. In developing countries, extrapulmonary TB often presents as an acute abdomen in surgical emergencies such as perforations and obstructions of the gut. Abdominal TB in different forms has been found more often as an aetiology for the chronic abdomen. This paper aims to evaluate TB as a surgical problem.

Methods

A comprehensive review of the literature on abdominal TB was undertaken. PubMed searches for articles listing abdominal TB/different types/diagnosis/treatment (1980–2012) were performed.

Results

TB is still a global health problem and the abdomen is one of the most common sites of extrapulmonary TB. Presentation may vary from an acute abdomen to a number of different chronic presentations, which can mimic other abdominal diseases. While some may benefit from antitubercular therapy, others may develop surgical problems such as strictures or obstruction, which may necessitate surgical intervention.

Conclusions

Abdominal TB should always be considered one of the differential diagnoses of acute or chronic abdomen in endemic areas.

Keywords: Abdominal tuberculosis, Diagnosis, Treatment

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in developing countries.1 Abdominal TB has been a great concern for surgeons as its prevalence has been found to be as high as 12% in cases with extrapulmonary TB.1,2 Gastrointestinal TB is the sixth most common form of extrapulmonary TB3 with acute presentations (eg perforation and obstruction) and a variety of chronic problems (eg vague ill health, anorexia, weight loss, malabsorption syndrome, subacute intestinal obstruction).2 In India, TB is responsible for 5–9% of all cases of small intestinal perforations.3 Abdominal TB predominately affects young adults.3,4

Methods

A systematic search of the literature was performed to determine the diagnostic procedure relevant to abdominal TB and its different treatment modalities. This comprised a comprehensive search of PubMed using the following keywords: ‘abdominal tuberculosis’, ‘different types’, ‘diagnostic procedures’ and ‘treatment methods’ (including all related terms). The search was performed separately by the authors. Abstracts were reviewed and after omission of duplicates, relevant papers were retrieved.

Pathology and pathogenesis

The most common route of infection is by ingestion/swallowing of contaminated materials such as infected sputum or milk. The second route is via haematogenous spread from a distant primary focus (lungs) and, rarely, direct spread from the adjacent infected structures such as the fallopian tubes.5 Ingestion of infected milk has become rare in the West since the pasteurisation of milk and in developing countries, since the habit of boiling milk developed. Bacilli isolated in patients with abdominal TB are therefore mostly Mycobacterium tuberculosis and not Mycobacterium bovis.6–8

After ingestion, the organism is trapped in the Peyer’s patches of the small intestine and carried by macrophages through the lymphatics to the adjacent mesenteric lymph nodes, where they remain dormant. Suppression of the host defence due to malnutrition, diabetes, renal failure and immunosuppression/human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) increases the risk of reactivation of a dormant focus. Half (50%) of HIV patients with TB have extrapulmonary involvement, compared with only 10–15% of TB patients who are not infected with HIV.9,10

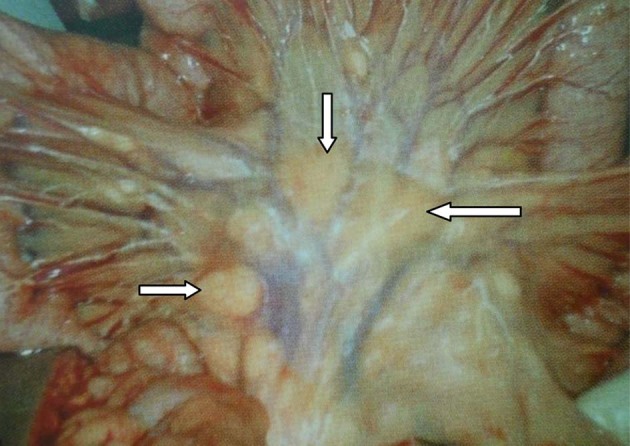

Abdominal TB involves the gastrointestinal tract (Figs 1 and 2), peritoneum, lymph nodes and solid viscera (eg liver, spleen), each of which can be acute or chronic.

Figure 1.

Abdominal tuberculosis with small gut involvement (arrows)

Figure 2.

Multiple enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes (arrows)

Gastrointestinal tuberculosis

The gastrointestinal tract is involved in 65–78% of cases.8,11 The peritoneum and lymph nodes are commonly involved. Although gastrointestinal TB can manifest itself in the oesophagus, stomach, duodenum, appendix, large bowel and anorectal area,12 the most common site of involvement is the ileum and ileocaecal region.11,13–15

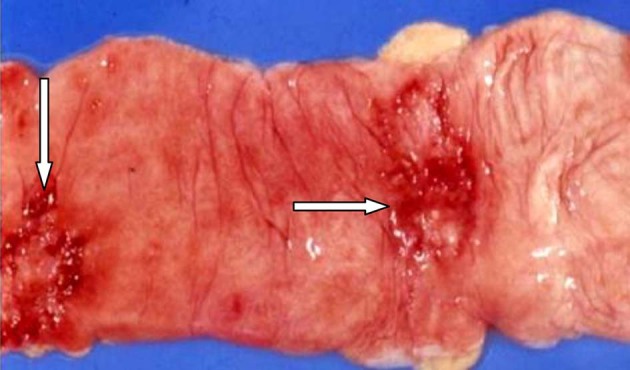

Intestinal lesions

Inflammatory enlargement of the Peyer’s patches leads to mucosal ulcerations. Endarteritis may lead to ischaemia and development of strictures. Fibrosis may follow and can result in typical ‘napkin ring’ strictures. Small intestinal strictures may be multiple in nature (Fig 3). They may present as acute or subacute intestinal obstruction clinically.

Figure 3.

Transverse ulcers with undermined edges (arrows)

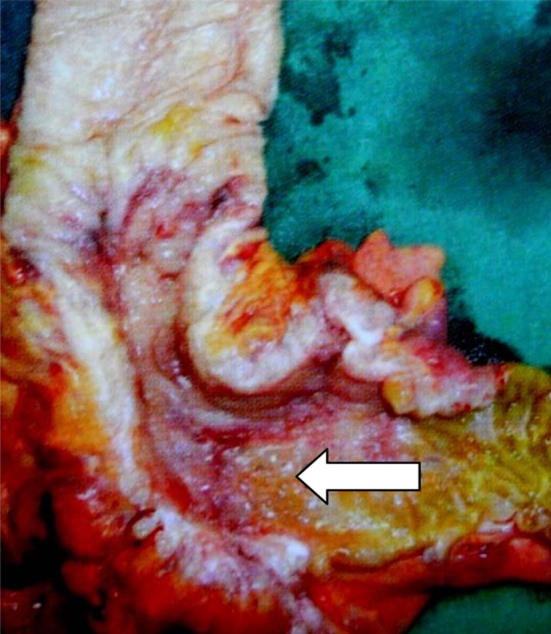

Three types of intestinal lesions are seen: ulcerative, stricturous and hypertrophic. Ulcerative and stricturous lesions are common in the small intestine (Fig 4). Ulcerohypertrophic lesions resulting from extensive inflammation of submucosa and subserosa are mostly found in the ileocaecal region. Isolated segmental colonic TB has also been reported.16,17

Figure 4.

Resected part of ileocaecal region showing stricturous lesion (arrow) in the terminal ileum

Mesenteric lymph nodes may become enlarged and caseate, leading to intra-abdominal abscesses. Loops of ileum, mesentery and lymph nodes may form a mass known as the ‘abdominal cocoon’ (Fig 5).18

Figure 5.

Interloop adhesion and abdominal cocoon (arrows)

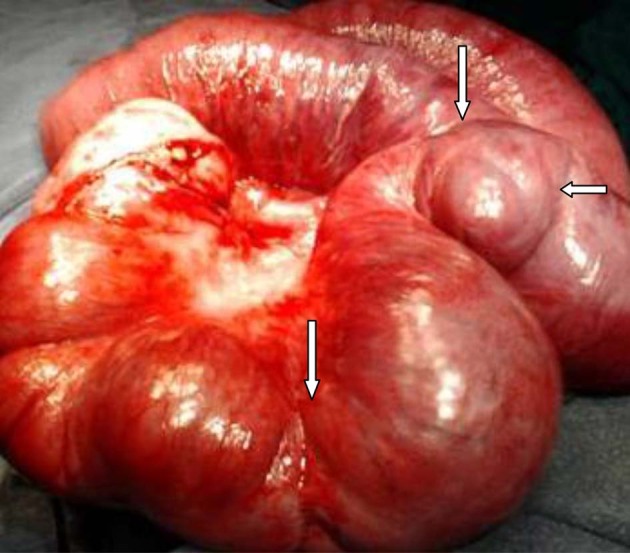

Tuberculous peritonitis

Peritoneal involvement presents as multiple miliary tubercles on the peritoneal and intestinal surfaces (Fig 6).10 There may be thickened omentum, which is felt as a transverse band across the abdomen and commonly referred to as rolled up omentum in TB.10

Figure 6.

Peritoneal involvement of tuberculosis (arrow)

Diffuse peritoneal involvement may present as the ascitic, fibrous, encysted or purulent variety. The ascitic type has straw coloured fluid while the fibrous type has adhesions of intestines and viscera with less fluid. The encysted and loculated types have adhered intestines enclosing a cavity of serous fluid. The purulent type is rare.12

Clinical features

The disease can occur at any age but is more common in young adults.3,4 The mean age of patients is 30–40 years.1 Alhough some suggest women suffer more than men, the disease is seen equally in both sexes.1,12 The clinical picture of abdominal TB is different in children to that in adults. About 90% of features in children are due to the involvement of the peritoneum and lymph nodes.1 Symptoms related to intestinal lesions are seen in about 10% of cases.1,19

Abdominal TB is noted for its diverse presentations, which can mimic many clinical conditions. It may have an acute, chronic or acute-on-chronic presentation, or it could be a pure incidental finding. While peritoneal and lymph node involvement contributes in the majority of cases,20 the clinical spectrum depends on the site and type of pathology. Patients have malabsorption in 21–75% of cases.6,11 Many patients experience a mobile lump in the abdomen, which may be tender at times.1 Some may experience bouts of subacute intestinal obstruction marked by colicky pain, distension, vomiting, gurgling and a feeling of relief after passage of flatus. Rectal bleed occurs in few cases and massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding is rare. Anorectal TB can present as stricture, fistula-in-ano or an anal fissure.

Gastroduodenal TB may mimic peptic ulcer,21 carcinoma or it may present with perforation.1 TB of the oesophagus and pancreas may be confused with cancers of the relevant areas.

Tubercular peritonitis with ascites may present with less tenderness and guarding than pyogenic peritonitis with perforation. An encysted collection may present as a lump anywhere in the peritoneal cavity while mesenteric lymph nodes present mostly as a lump in the centre of the abdomen. Portal hypertension and obstructive jaundice have been noted due to compression of the portal vein and common bile duct by enlarged lymph nodes.1

About 30% of patients have systemic manifestations such as low grade fever, rise of temperature in the evening, lethargy, malaise, night sweats and weight loss.6 This is more commonly seen with the ascitic type of tubercular peritonitis and ulcerative lesions of the intestine.1

An acute abdomen may be due to intestinal obstruction (in acute or acute-on-chronic cases), acute mesenteric lymphadenitis, peritonitis, perforations proximal to a stricture or acute tubercular appendicitis.1,22

Differential diagnoses

Kapoor has discussed the differential diagnoses of TB.1 These can be divided into those for different pathologies.

Intestinal pathology

The intestinal lesions in TB can present as ulcers, strictures, hypertrophic lesions or perforations. Ulcerative lesions need to be differentiated from similar lesions encountered in coeliac disease, immunoproliferative diseases and tropical sprue. Tubercular strictures may be confused with strictures in Crohn’s disease and a carcinoma of the ileocaecal region. Hypertrophic lesions found in malignancy, amoebomas, actinomycosis and appendicular lumps may mimic lesions of tubercular origin. Enteric perforations may be confused with tubercular perforations.

Peritoneal pathology

Ascites due to cirrhosis of the liver, congestive cardiac failure and malnutrition are similar to tubercular peritonitis. Peritoneal tubercles of carcinomatosis may be confused with tubercular lesions of the peritoneum, and mesenteric and ovarian cysts are often confused with encysted tubercular collections of the peritoneum. Although rare, the purulent variety of tubercular peritonitis needs to be differentiated from pyoperitoneum due to perforation of a hollow viscus.

Investigations

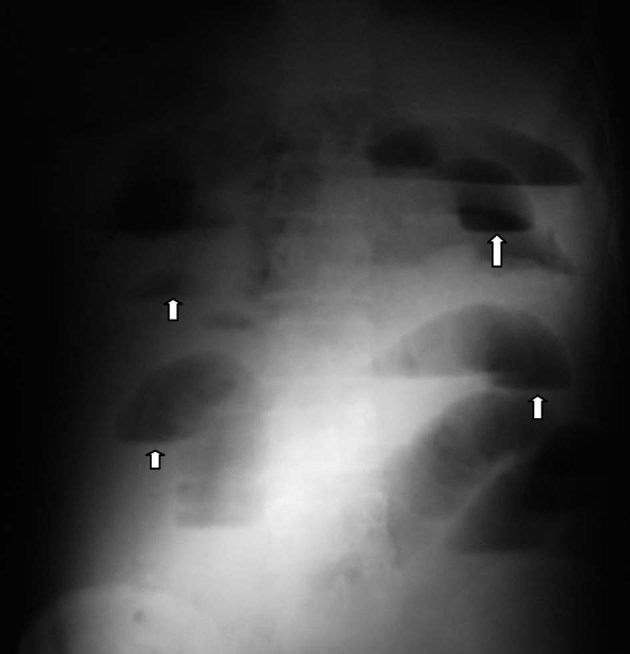

The diagnosis of abdominal TB is challenging.20 Chest radiography may show concomitant pulmonary disease in 7–72% of patients.15 In reality, a healed focus of TB is found in 39% of cases.23 In an acute abdomen, an erect abdominal x-ray may show dilated loops of jejunum or ileum with air–fluid levels (Fig 7) suggesting subacute or acute intestinal obstruction.

Figure 7.

X-ray showing small bowel obstruction with multiple air–fluid levels (arrows) due to abdominal tuberculosis

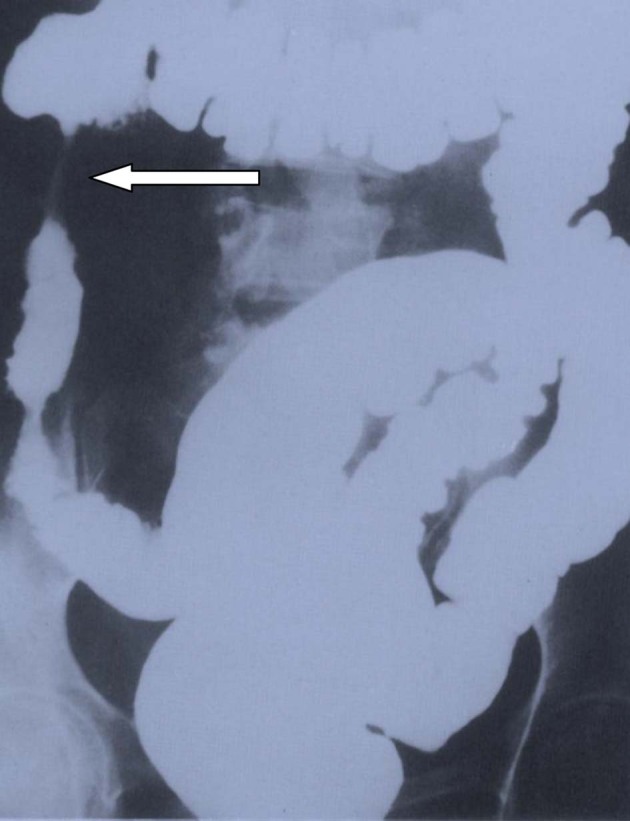

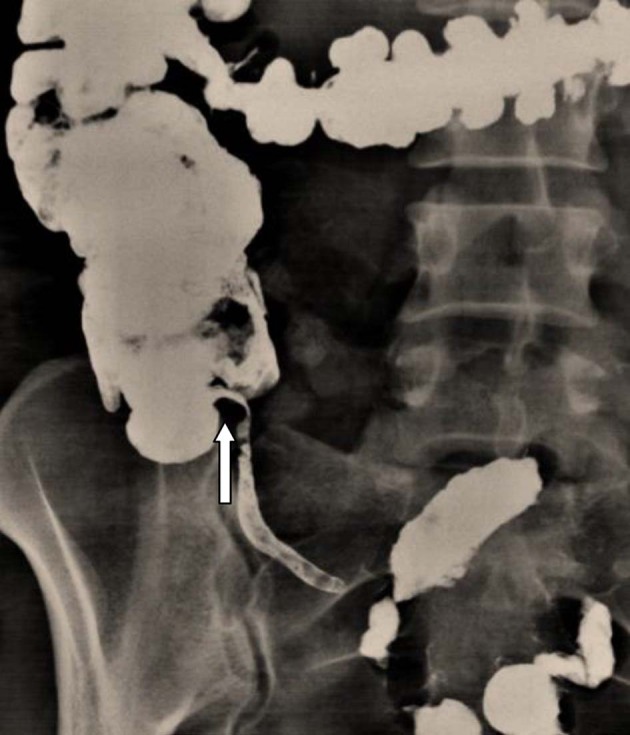

In cases of ileocaecal TB, a double contrast barium enema may show a shortened ascending colon with a deformed/shortened or narrowed caecum (Figs 8 and 9). The ileocaecal valve can distort with incompetence. The ileocaecal junction may seem deformed with the ileocaecal junction at an obtuse angle.1 The Fleischner sign is the narrowing of the terminal ileum and the Stierlin sign is a fibrotic terminal ileum opening into a contracted caecum. Barium studies can give false results in about 25% of cases and they fail to differentiate TB from Crohn’s disease and malignancy.15

Figure 8.

Terminal ileum (arrow) drawn upward into the ascending colon

Figure 9.

Narrowing of ileocaecal junction with upward pulling of caecum (arrow)

Ultrasonography evaluates ascites, enlarged nodes and hyperplastic lesions. Ultrasonography guided ascitic tap or fine needle aspiration from enlarged lymph nodes or hypertrophic lesions may be informative.1

Computed tomography (CT) demonstrates the adhesion of bowel loops (Fig 10) and thickened omentum with irregular soft tissue densities.24 CT can also evaluate lymph nodes.1

Figure 10.

Computed tomography showing interloop adhesion and intestinal cocoon (arrows) with enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes (arrow head)

Colonoscopic evaluation of intestinal TB shows friable mucosa with nodularity as well as irregular ulcers with well defined margins and undermined edges. Pseudopolyps and cobblestoning need to be differentiated from Crohn’s disease and malignancy.16 Colonoscopic biopsy may not reveal granulomas in all cases, as the lesions are submucosal.17

Laparoscopy is now becoming the diagnostic procedure of choice. It is rapid, safe and accurate. It allows biopsy of typical tubercles in the peritoneum and other organs with an accuracy of 75%. Both lymphoma and carcinomatosis can be excluded.25 Diagnostic laparotomy may be performed when endoscopic/laparoscopic procedures are not possible.

Management

All patients with abdominal TB should receive a full course of antitubercular therapy. The World Health Organization guidelines recommend a six-month course: four drugs (isoniazide/rifampicin/pyrazinamide/ethambutol/streptomycin) for two months followed by two drugs (isoniazide/rifampicin) for four months.10 Uncomplicated tuberculous enteritis can be managed with 9–12 months of chemotherapy with 2 months of intensive 4-drug treatment followed by 7 months of 2-drug treatment.

Surgical treatment

About 20–40% patients with abdominal TB present with an acute abdomen and need emergency surgical management.26 Chronic patients with subacute obstruction are managed conservatively and surgery is planned after suitable workup.27

Tubercular perforations are mostly ileal and proximal to a stricture. If they are close to one another, resection of the segment is performed. If the stricture is not close, the perforation can be closed in layers and the stricture is dealt with by strictureplasty or resection, depending on the length of the narrowed segment. Multiple strictures in a segment may require resection and anastomosis.28,29 Strictures of recent onset that are not very tight may be left alone or dilated through an enterotomy.28,29 Bypass procedures are not preferred to resections owing to the possibility of future obstructions and malabsorption.1

Acute tubercular peritonitis and mesenteric lymphadenitis need to be managed with caution. If a laparotomy is carried out, only a biopsy needs to be performed with peritoneal toilet and the abdomen should be closed without a drain.1

All patients with ileocaecal TB must be offered antitubercular chemotherapy. Patients who develop complications such as obstruction can be operated on safely with a right hemicolectomy.1,13 The choice of surgery has become more conservative, and limited ileocaecal resection and anastomosis is preferred to right hemicolectomy.23

Postoperative complications include anastomotic leak, faecal fistula, peritonitis, intra-abdominal sepsis, persistent obstruction, wound infection and dehiscence.11,13 Reoperation may be required for recurrent obstruction.

Delayed diagnosis and injudicious treatment are principally responsible for the mortality rate of 4–12%.1 The high mortality is partly associated with malnutrition, anaemia and hypoalbuminaemia; mortality is higher (12–25%) in the presence of acute complications.11

Our experience with abdominal tuberculosis

Over the last 25 years, we have explored many emergency cases. We have dealt with perforations, strictures leading to obstruction, multiple adhesion and different forms of peritoneal TB. All of these patients did extremely well with antitubercular therapy postoperatively.

Chronic problems such as subacute obstruction, constipation, anorexia, loss of weight, ascites need a high index of clinical suspicion. While some patients may benefit from a conservative approach with antitubercular therapy, others may develop surgical problems such as strictures or obstruction, which may necessitate surgical intervention. In our experience, abdominal TB should be considered a surgical problem in cases of both acute and chronic abdomen.

Conclusions

A high index of suspicion in populations where TB is common (eg India), timely diagnosis using radiology, imaging and endoscopy, and judicious management with a combined therapy of antitubercular drugs and conservative surgery can reduce the mortality of this curable yet potentially lethal disease.

References

- 1.Kapoor VK. Abdominal tuberculosis. Postgrad Med J 1998; 74: 459–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CH, Yang CC, Yeh YH, et al. Pancreatic tuberculosis with obstructive jaundice – a case report. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 2,534–2,536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma MP, Bhatia V. Abdominal tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res 2004; 120: 305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanrikulu AC, Aldemir M, Gurkan F, et al. Clinical review of tuberculous peritonitis in 39 patients in Diyarbakir, Turkey. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 20: 906–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereira JM, Madureira AJ, Vieira A, Ramos I. Abdominal tuberculosis: imaging features. Eur J Radiol 2005; 55: 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tandon HD. The pathology of intestinal tuberculosis and distinction from other diseases causing stricture. Trop Gastroenterol 1981; 2: 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharp JF, Goldman M. Abdominal tuberculosis in East Birmingham – a 16 year study. Postgrad Med J 1987; 63: 539–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vij JC, Malhotra V, Choudhary V, et al. A clinicopathological study of abdominal tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc 1992; 39: 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldman KP. AIDS and tuberculosis. Tubercle 1988; 69: 71–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar S, Pandey HI, Saggu P. Abdominal Tuberculosis. : Taylor I, Johnson C. Recent Advances in Surgery. 28th edn. London: RSM; 2005. pp47–58. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhansali SK. Abdominal tuberculosis. Experiences with 300 cases. Am J Gastroenterol 1977; 67: 324–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed ME, Hassan MA. Abdominal tuberculosis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1994; 76: 75–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joshi MJ. The surgical management of intestinal tuberculosis – a conservative approach. Indian J Surg 1978; 40: 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer KR, Patil DH, Basran S, et al. Abdominal tuberculosis in urban Britain – a common disease. Gut 1985; 26: 1,296–1,305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tandon RK, Sarin SK, Bose SL, et al. A clinico-radiological reappraisal of intestinal tuberculosis – changing profile? Gastroenterol Jpn 1986; 21: 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah S, Thomas V, Mathan M, et al. Colonoscopic study of 50 patients with colonic tuberculosis. Gut 1992; 33: 347–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh V, Kumar P, Kamal J, et al. Clinicocolonoscopic profile of colonic tuberculosis. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91: 565–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaushik R, Punia RP, Mohan H, Attri AK. Tuberculosis abdominal cocoon – a report of 6 cases and review of the literature. World J Emerg Surg 2006; 1: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma AK, Agarwal LD, Sharma CS, Sarin YK. Abdominal tuberculosis in children: experience over a decade. Indian Pediatr 1993; 30: 1,149–1,153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.al-Hadeedi S, Walia HS, al-Sayer HM. Abdominal tuberculosis. Can J Surg 1990; 33: 233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukerjee P, Chopra I. Gynaecological tuberculosis in relation to abdominal tuberculosis. Proc Assoc Surg E Afr 1979; 2: 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rangabashyam N, Anand BS, OmPrakash R. Abdominal Tuberculosis. : Morris PJ, Wood WC. Oxford Textbook of Surgery. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp3 ,237–3, 249. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prakash A. Ulcero-constrictive tuberculosis of the bowel. Int Surg 1978; 63: 23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bankier AA, Fleischmann D, Wiesmayr MN, et al. Update: abdominal tuberculosis – unusual findings on CT. Clin Radiol 1995; 50: 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hossain J, Al-Aska AK, Al Mofleh I. Laparoscopy in tuberculous peritonitis. J R Soc Med 1992; 85: 89–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dandapat MC, Mohan Rao V. Management of abdominal tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc 1985; 32: 126–129. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhansali SK. Abdominal tuberculosis. Experiences with 300 cases. Am J Gastroenterol 1977; 67: 324–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katariya RN, Sood S, Rao PG, Rao PL. Stricture-plasty for tubercular strictures of the gastro-intestinal tract. Br J Surg 1977; 64: 496–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pujari BD. Modified surgical procedures in intestinal tuberculosis. Br J Surg 1979; 66: 180–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]