Abstract

Objective

To assess the feasibility of prospectively collecting biological samples (urine) from palliative care patients in the last weeks of life.

Setting

A 30-bedded specialist hospice in the North West of England.

Participants

Participants were adults with a diagnosis of advanced disease and able to provide written informed consent.

Method

Potential participants were identified by a senior clinician over a 12-week period in 2014. They were then approached by a researcher and invited to participate according to a developed recruitment protocol.

Outcomes

Feasibility targets included a recruitment rate of 50%, with successful collection of samples from 80% who consented.

Results

A total of 58 patients were approached and 33 consented (57% recruitment rate). Twenty-five patients (43%) were unable to participate or declined; 10 (17%) became unwell, too fatigued, lost capacity, died or were discharged home; and 15 (26%) refused, usually these patients had distressing pain, low mood or profound fatigue. From the 33 recruited, 20 participants provided 128 separate urine samples, 12 participants did not meet the inclusion criteria at the time of consent and 1 participant was unable to provide a sample. The criterion for a urinary catheter was removed for the latter 6 weeks. The collection rate during the first 6 weeks was 29% and 93% for the latter 6 weeks. Seven people died while the study was ongoing, and another 4 participants died in the following 4 weeks.

Conclusions

It is possible to recruit and collect multiple biological samples over time from palliative care patients in the last weeks and days of life even if they have lost capacity. Research into the biological changes at the end of life could develop a greater understanding of the biology of the dying process. This may lead to improved prognostication and care of patients towards the end of life.

Keywords: STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first investigation to prospectively collect biological samples from patients towards the end of life and in the dying phase.

The study raises the possibility of conducting systemic research into the biological changes in patients towards the end of life.

All of the participants who subsequently died on the study had a cancer diagnosis. It therefore does not accurately reflect the dying process patients with a non-cancer diagnosis go through.

The study was found to be acceptable to patients, their families and the staff; however, there was no formal process used to assess this.

The protocol described can be used in future research.

Introduction

Clinicians find it difficult to diagnose accurately when someone is dying. There is no evidence-based method of consistently and accurately estimating an advanced cancer patient's prognosis. Existing methods of predicting prognosis are no more accurate than a multiprofessional prognostic estimate.1 Uncertainty has been recognised by healthcare professionals as a great barrier to the provision of good palliative care.2 This prognostic uncertainty may lead to a lack of appropriate intervention or prompt inappropriate and burdensome interventions. Accurate prognostication is crucial for patients, their families, the treating medical teams and healthcare providers to plan and provide the best possible care for patients at the end of life.

Understanding of the biological process of dying is limited. The current evidence base informing terminal care is largely descriptive, retrospective or extrapolated, and there are no empirical studies investigating biochemical changes during the dying process.3 A review of end-of-life care in the UK and the National Care of the Dying audit in hospitals conducted in England both recommended research into the recognition of dying.4 5 The collection of biological samples would allow for the use of systemic research methods including molecular and metabolomic approaches to investigate the dying process.

Conducting research to understand the biological processes at the end of life is difficult due to the numerous logistical, practical and ethical challenges of collecting data at this time. Obstacles to research include the following: the heterogeneous nature of the patient population due to variants in primary disease and concomitant and independent comorbidities, the high prevalence of cognitive problems which affect capacity, the unstable nature of the disease process, the lack of research infrastructure and experience in palliative care teams and ‘gatekeeping’ (ie, preventing access to potential research participants by clinical staff).6 However, research is essential to improve patient care and for palliative care to develop as an evidence-based specialty.7

In this paper, we evaluated the feasibility of collecting multiple biological samples (urine) from hospice patients in the last weeks and days of life, including patients who lost the capacity to give consent.

Methods

Setting and participants

The study was conducted at a 30-bedded specialist hospice in the North West of England over a 12-week period during 2014. The hospice provides care for patients with life-limiting diseases with cancer and non-cancer diagnoses. Ethics approval was provided by North Wales (West) Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 13/WA/0266). Participants were enrolled in the study, provided that they met eligibility criteria (table 1), and informed consent was provided.

Table 1.

Study inclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

*During the first 6 weeks of the study, a urinary catheter was part of the inclusion criteria. With an amendment to the research ethics approval, this requirement was withdrawn for the latter 6 weeks of the study to facilitate increased participation.

Enrolment procedure

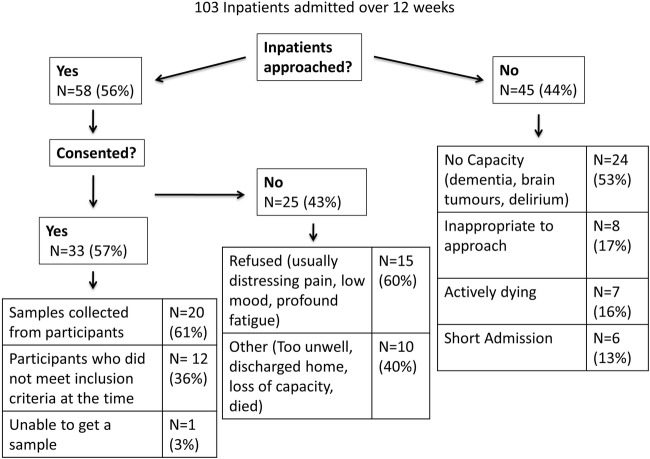

The research method, including participant selection, was designed to minimise the potential for distress caused by recruiting in this challenging and emotive phase of life. There was extensive discussion among the team and consultation with a patient advisory group about the title on the documents used—‘Investigation of the biological changes in urine towards the end of life—a feasibility study’. All existing and new inpatients at the hospice were considered potential participants. A senior doctor (registrar or consultant) on the clinical team reviewed each inpatient to evaluate whether an approach about participation in the study would cause distress. If deemed appropriate, the patient was provided with a one-page introductory patient information leaflet and permission for a research team member to approach was requested. Prior to the study starting, education sessions were held with the hospice staff to outline the purpose of the study and what would be involved. A research team member then approached the potential participant and discussed a detailed three-page patient information leaflet, which explained the purpose of the study as follows: “we plan to analyse the urine of patients with advanced disease and how this changes towards the end of life. There is very little known about changes in a person's body at this incredibly important time. By doing this study we want to examine if the physical experiences of the patient can be seen in the genes and in the chemicals found in urine.” The patient was encouraged to involve their family in their decision-making and was given appropriate time (minimum 24 hours) to consider their participation and have the opportunity for further discussion with their family, friends, hospice clinical staff or research team. The patient's agreement to enter the study was documented, and the signed consent form was placed in the medical notes; a copy was also given to the patient, and an additional copy was kept for the research site file. Medical records and medication charts were reviewed to collect the age, race, diagnosis and, if appropriate, known metastases, comorbidities, medications, smoking status and catheter system used. Some participants were asked to clarify demographic questions. Once informed consent was obtained and all inclusion criteria were met, sample collection began. Participating patients who were discharged from the hospice and subsequently readmitted were asked to reconfirm their consent to participate verbally. The process for enrolment is outlined in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Process for enrolment.

Sample collection

Since potential participants could lose the ability to provide consent as the study progressed, participants were asked specifically whether they agreed to continue with sample collection should they lose the ability to consent. Prior to sample collection, the capacity of the participant was assessed for ongoing assent to collect samples. If a participating patient's clinical condition deteriorated to the extent that the patient lost capacity to consent to sample collection, then a consultee was identified to advise the researcher about the participant's ongoing continuation in the study. The consultee was selected as per ‘Guidance on nominating a consultee for research involving adults who lack capacity to consent’ (Department of Health, UK). Initially, a personal consultee was consulted for advice. They were ideally someone who knew the participant well but were not acting in a professional or paid capacity, for example, next of kin, immediate family, relatives or friends. If a personal consultee was not identified or unable to attend the hospice, then the researcher nominated a healthcare professional (a hospice doctor or nurse who was involved in the patient's care), unconnected with the research who was willing to act as a nominated consultee. The nominated consultee then contacted a family member and listened to their views if it was the first time that the participant was unable to give consent. The ‘consultee’ was given a ‘consultee information leaflet’ and given time to consider it. If after reading this they were in agreement with the participant continuing in the study, they were asked to sign a ‘consultee declaration form’. Only then was a sample collected. If the participant continued to lack capacity, then permission to collect urine was sought from the personal (or nominated) consultee each time a sample was collected.

Withdrawal of participants

Patients were informed verbally and with the patient information leaflet that they could withdraw from the study at any time and no reason for withdrawal was required. It was emphasised that their clinical care would not be affected. If a participant withdrew from the study or the consultee requested withdrawal, no reason was required. However, when they shared their reason with the research team or a member of the healthcare staff, this was recorded in the study database.

Sample collection

Biological samples were collected three times a week by the research team. Research team members collected 20 mL of urine from participants in a universal container. For those participants with a urinary catheter, the urine was collected using a needle and syringe from the catheter port. The samples were stored on site in a locked freezer at −20°C. An anonymised record of the medication administered was collected.

Feasibility criteria

We designed a priori criteria which included the following conditions: recruitment rate of at least 50% and the collection of urine samples from 80% of those who consented. There are no established precedents for what constitutes successful recruitment within a feasibility study of this type. However, we have engaged the outcomes from the Prognosis in Palliative care Study (PiPS), which is the closest in terms of focus to set the bar for recruitment. The PiPS study recruited 43% within a hospice setting, and we decided to target 50%.1 Hagen et al state that palliative care studies can have attrition rates of 50% or higher.8 Despite this, we aimed for a collection rate of 80%.

Statistical analysis

The primary reason for this study was to establish feasibility of collecting biological samples from patients in the last weeks of life. The target sample size was n=20, which was determined primarily based on feasibility considerations to test procedures for a larger study. The sociodemographic and outcome variables are reported using descriptive measures including the mean for continuous variables and number (per cent) for categorical variables. The analysis of feasibility outcomes was descriptive in nature, with the results expressed as percentages and feasibility assessed against the corresponding targets.

Results

In total, 128 separate samples from 20 different participants were collected (see table 2). Four participants lost capacity while on the study, and the consultee declaration form worked well in facilitating the continued sample collection for these participants.

Table 2.

Summary of participant details and samples collected

| Age (years) | |

| Range | 50–90 |

| Mean | 70.6 |

| Median | 67.5 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 9 |

| Female | 11 |

| Diagnosis (number of cases) | |

| Cancer | |

| Lung | 6 |

| Breast | 3 |

| Colorectal | 3 |

| Prostate | 3 |

| Ovarian | 1 |

| Gastric | 1 |

| Renal | 1 |

| Non-malignant | |

| Multisystem atrophy | 1 |

| Motor neuron disease | 1 |

| Number of samples collected | |

| Range | 1–18 |

| Mean | 6 |

| Median | 5 |

| Number of samples collected in the weeks before dying | |

| Week 1 | 15 samples from 6 participants |

| Week 2 | 17 samples from 9 participants |

| Week 3 | 21 samples from 8 participants |

| Week 4 | 10 samples from 6 participants |

| Participants in the last 4 weeks of life | 11 |

| Participants alive more than 3 months after the study | 6 |

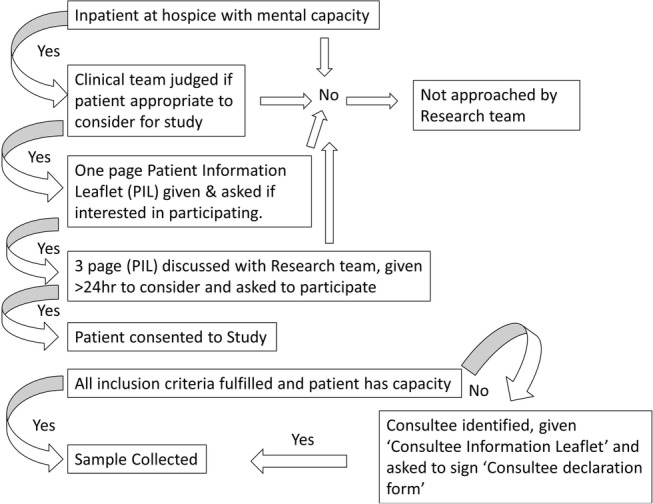

Fifty-six per cent (n=58) of inpatients at the hospice were approached. Of the patients who were not approached, 53% did not have capacity (eg, dementia, brain primary or secondary, delirium), 16% were actively dying, 13% had too short an admission and 17% were deemed inappropriate to approach (anxiety 13%, anger 2%, low mood 2%).

From the 58 patients approached, 33 consented to participate in the study (57%). No problems were identified with the information leaflets and consent form used. Only one patient asked a researcher to leave during the discussion of the patient information leaflet.

The protocol used was found to be acceptable to participants, their families and staff, and no episodes of distress were encountered. This was not formally assessed; however, no symptoms were received regarding the discussion of the study protocol in recruitment, or the collection of study data and only one patient asked a researcher to leave during the discussion of the patient information leaflet. One participant withdrew from the study (5%). One patient who consented and discharged was readmitted and reconsented during the study.

Of the 43% who did not consent, 40% of those approached became unwell, too fatigued, lost capacity, died or were discharged home. The remaining 60% refused; usually, these patients had distressing pain, low mood or profound fatigue. This is summarised in figure 2.

Figure 2.

A summary of the patients approached and consented during the study.

Within the first 6 weeks of the study, 17 patients consented to participate. As a urinary catheter was part of the study inclusion criteria, only five of these participants were eligible to have samples collected (collection rate of 29%). Owing to the high consent rate and low collection rate early in the study, an amendment to the Research Ethics Committee was made to remove having the urinary catheter as part of the inclusion criteria. During the latter 6 weeks, following the approved amendment to the protocol, 15 participants were recruited (collection rate of 93%). Samples were not collected from one patient despite multiple attempts over a 2-week period. One patient asked to withdraw from the study after the collection of one urine sample as it was felt ongoing collection was considered too burdensome. Seven people died, while the study was ongoing and another four participants died in the following 4 weeks.

Discussion

Research into the physiology of the dying process is difficult. This paper describes a protocol for the collection of biological samples (urine) from hospice patients towards the end of life and during the dying process. There was a 57% recruitment rate of inpatients and a collection rate of 93% when urine was collected from participants with or without a urinary catheter. A total of 128 separate samples from 20 different participants were collected over the 12-week period.

The study confirms the ability to prospectively recruit patients and collect multiple urine samples towards the end of life and in the dying phase, including when a person has lost the capacity to give consent. The protocol used was found to be acceptable, although this was not formally assessed. One participant withdrew from the study (5%). Attrition rates of 50% and even higher have been described in other palliative care studies.8 The methodology used benefited greatly from the input of the patient representative group and by asking the medical team to screen patients before a researcher approached. Four participants lost capacity while on the study, and the consultee declaration form worked well in order to continue sample collection. The involvement of family through the consent process and sample collection helped in ongoing sample collection in those participants when mental capacity was lost. In fact, some patients and families derived meaning from being able to contribute to the study.

During the study, the requirement for a urinary catheter as a criterion for sample collection was removed after 6 weeks. This was due to the low recruitment rate (29%) when samples were collected from 5 out of 17 patients who had consented to the study. The change facilitated an increased recruitment rate (93%).

Challenges within the study

Challenges to sample collection included the necessity for sensitive communication skills, the timing of sample collection, patients who were unable to sign the consent form and patient fatigue. During the consenting process, finding the appropriate words to describe the rationale for the study required experience and training in advanced communication skills; both researchers were experienced palliative medicine physicians. Urine collection from participants who did not have a urinary catheter highlighted issues to be considered in future studies. Participants had variable mobility, and providing a urine sample could be inconvenient for them if they were not otherwise going to the toilet. One patient who consented to the study was unable to provide a sample despite 6 attempts over a 2-week period. Another patient was able to provide only one sample over the same time period. There were some participants who could initially provide samples, but over time as their disease progressed and their mobility decreased, samples became more difficult to collect, which caused gaps in sample collection. There were also times when it was challenging to engage with the medical teams, for example on ward round days. This sometimes caused a delay in the clinical team approaching a patient for initial consent. Other challenges included two participants who were unable to write their signature on the consent form, and those patients with severe fatigue who often felt unable either for the entire initial discussion or the subsequent follow-up meeting to consent to the study. Therefore, it would be important in any future work to keep the patient information leaflets and consent forms as short as possible.

The majority of participants recruited had a cancer diagnosis (90%), and all of the samples collected in participants who subsequently died had a cancer diagnosis. As a result, this cohort does not represent the dying process of people with a non-malignant diagnosis. Also, all of the participants recruited were of a white British background and were therefore not a broad cultural cross section of patients.

Palliative patients can have a variable prognoses ranging from years to days or hours. Those patients towards the end of life (in the last weeks of life) are an important and understudied patient population. It is imperative that no distress is caused to them or their families, and this is a concern to all parties involved in research. However, our protocol addresses these important concerns. In the hospice, we discussed with the treating team the appropriateness of patients being included in the study, for example whether the patient was aware of the advanced nature of their disease. This could be considered a form of gatekeeping.

Challenges for future research

This study highlights a cohort of patients who on admission to a hospice had already lost capacity and therefore could not take part in the study. In particular, this included patients with dementia, brain tumours and those actively dying. In the UK, the Mental Capacity Act of 2005 prevents the recruitment of patients to research studies who are unable to give consent. A future challenge in the UK will be to design studies to include this cohort of patients.

Prior studies do suggest that palliative patients want to participate in research,9 10 and our study confirms this. The consent rate of 57% of those approached was encouraging and affirmed the importance of conducting research into end-of-life care for these patients and their families. The PiPS which recruited palliative patients from 18 palliative services in the UK had a 43% recruitment in the hospice setting, demonstrating that access to palliative patients was significantly easier in the hospice as compared to other settings.6 The PiPS study and the Rees and Hardy study, which developed a process of advance consent to enable research to be undertaken in patients in the terminal phase, reported that very few patients were distressed when approached. Rees and Hardy also reported that the consent process can be very time consuming and emotionally draining for staff.11

Stone et al6 reported that obstacles to research include the nature of the patient population, the high prevalence of cognitive problems, the unstable nature of the disease process, the lack of research infrastructure and experience in palliative care teams and ‘gatekeeping’ (ie, preventing access to potential research participants by clinical staff). Stone et al also mention common reasons for inaccessibility of patients: died before review, gatekeeping, discharged before review, patients did not wish to see a researcher, non-competent patient and relatives unavailable, researcher unavailable and patient unavailable. Our own study reflected similar challenges, although we did not find gatekeeping to be an issue.

As reported by Rees and Hardy, patients on palliative care wards often have a poor performance status and are too unwell to read lengthy patient information sheets.11 They are therefore unable to give consent. In addition, patients are often reported to be too anxious to understand complex study descriptions.12 Therefore, from our experience and the experience of other studies, it is important in any future work to keep the patient information leaflets and consent forms as simple and as short as possible.6 13

Diagnosing when a patient with advanced cancer is in the last weeks or days of life is a challenge; currently, no diagnostic test is available.5 Accurate prognostic information is essential to coordinate and manage care in response to need, while avoiding burdensome and unnecessary interventions. Even though little is known about the biology of dying, it has been suggested that there may be a common process to dying.14 15 Future work will involve systemic research approaches including metabolomic and genomic analyses of the urine samples. The aim of this research would be to develop a greater understanding of the biological process of dying and identify potential biomarkers for the dying process.

Conclusion

This paper describes a study for the collection of biological samples from patients towards the end of life including those without capacity. Importantly, the protocol used minimises undue distress to patients or their families. By incorporating the consultee process, the protocol overcomes the legal and ethical requirements in patients who lose mental capacity. It is our hope that this protocol will aid others to collect samples from what is considered to be a difficult cohort of patients to study. Research into the biological changes at the end of life could develop a greater understanding of the dying process. This may lead to improved prognostication and care of patients towards the end of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the NIHR for the Academic Clinical Fellow post for SC, the Staff of the Marie Curie Hospice Liverpool and Marie Curie Palliative Care Institute Liverpool and to Elizabeth Wright and Brenda Hughes for their invaluable input.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Richard Latten at @LattRJ

Contributors: All authors were involved in critical review of the manuscript and have seen and approved the final version. Specific contributions are as follows. SC, RL, SM, CRM, ACN, JW, CP and JE involved in study conception and design. SC and AS involved in sample acquisition. SC, AS and SM drafted the manuscript. ACN, RL, CRM, JW, CP and JE revised the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: North Wales Research Ethics Committee—West. REC reference 13/WA/0266.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Gwilliam B, Keeley V, Todd C et al. Development of prognosis in palliative care study (PiPS) predictor models to improve prognostication in advanced cancer: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2011;343:d4920 10.1136/bmj.d4920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oishi A, Murtagh FE. The challenges of uncertainty and interprofessional collaboration in palliative care for non-cancer patients in the community: a systematic review of views from patients, carers and health-care profession. Palliat Med 2014;28:1081–98. 10.1177/0269216314531999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plonk WM Jr, Arnold RM. Terminal care: the last weeks of life. J Palliat Med 2005;8:1042–54. 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal College of Physicians. National care of the dying audit for hospitals, England London: RCP 2014.

- 5.Neuberger J. More Care, Less Pathway: A Review of the Liverpool Care Pathway. London: Department of Health UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone PC, Gwilliam B, Keeley V et al. Factors affecting recruitment to an observational multicentre palliative care study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:318–23. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hermet R, Burucoa B, Sentilhes-Monkam A. The need for evidence-based proof in palliative care. Eur J Palliat Care 2002;9:104–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Brasher PM et al. Formal feasibility studies in palliative care: why they are important and how to conduct them. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;42:278–89. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terry W, Olson LG, Ravenscroft P et al. Hospice patients’ views on research in palliative care. Intern Med J 2006;36:406–13. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01078.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nwosu AC, Mayland CR, Mason S et al. Patients want to be involved in end-of-life care research. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:457 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rees E, Hardy J. Novel consent process for research in dying patients unable to give consent. BMJ 2003;327:198 10.1136/bmj.327.7408.198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Hays JC et al. Identifying, recruiting, and retaining seriously-ill patients and their caregivers in longitudinal research. Palliat Med 2006;20:745–54. 10.1177/0269216306073112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook AM, Finlay IG, Butler-Keating RJ. Recruiting into palliative care trials: lessons learnt from a feasibility study. Palliat Med 2002;16:163–5. 10.1191/0269216302pm551xx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reuben DB, Mor V, Hiris J. Clinical symptoms and length of survival in patients with terminal cancer. Arch Intern Med 1988;148:1586–91. 10.1001/archinte.1988.00380070082020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadhim H, Deltenre P, De Prez C et al. Interleukin-2 as a neuromodulator possibly implicated in the physiopathology of sudden infant death syndrome. Neurosci Lett 2010;480:122–6. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]