Abstract

Introduction

The reported number of new leprosy patients has barely changed in recent years. Thus, additional approaches or modifications to the current standard of passive case detection are needed to interrupt leprosy transmission. Large-scale clinical trials with single dose rifampicin (SDR) given as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to contacts of newly diagnosed patients with leprosy have shown a 50–60% reduction of the risk of developing leprosy over the following 2 years. To accelerate the uptake of this evidence and introduction of PEP into national leprosy programmes, data on the effectiveness, impact and feasibility of contact tracing and PEP for leprosy are required. The leprosy post-exposure prophylaxis (LPEP) programme was designed to obtain those data.

Methods and analysis

The LPEP programme evaluates feasibility, effectiveness and impact of PEP with SDR in pilot areas situated in several leprosy endemic countries: India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Tanzania. Complementary sites are located in Brazil and Cambodia. From 2015 to 2018, contact persons of patients with leprosy are traced, screened for symptoms and assessed for eligibility to receive SDR. The intervention is implemented by the national leprosy programmes, tailored to local conditions and capacities, and relying on available human and material resources. It is coordinated on the ground with the help of the in-country partners of the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations (ILEP). A robust data collection and reporting system is established in the pilot areas with regular monitoring and quality control, contributing to the strengthening of the national surveillance systems to become more action-oriented.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained from the relevant ethics committees in the countries. Results and lessons learnt from the LPEP programme will be published in peer-reviewed journals and should provide important evidence and guidance for national and global policymakers to strengthen current leprosy elimination strategies.

Keywords: leprosy transmission, post-exposure prophylaxis, contact tracing, contact screening, rifampicin

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Includes sites in six leprosy endemic countries and is complemented by sites in two additional countries to answer key questions of contact tracing and single dose rifampicin post-exposure prophylaxis (SDR PEP) feasibility and impact across various health systems in Asia, Africa and South America.

Implementation and coordination by national programmes will help to facilitate PEP integration into national strategies and thus ensure sustainability.

Expert guidance and close monitoring ensures quality data collection and analysis.

Results may not be fully relevant for countries with fundamentally different health systems and low-endemic areas.

Differing contact definitions limit the potential to pool results, and a focus on household members in some countries may reduce the impact of SDR PEP.

Introduction

Over the past 30 years, the prevalence of diagnosed leprosy cases has declined by 95%, from 5.2 million in 1985 to <200 000 in 2015.1 2 This remarkable reduction has often been cited as a major public health success. Indeed, in 2000, the WHO's goal to eliminate leprosy as a public health problem, defined as a prevalence of <1 leprosy patient per 10 000 population, was officially reached.3 This contributed to a sharp decline in official interest for leprosy in most endemic countries, and a significant reduction in financial support for national programmes that manifested itself in reduced case finding and diagnosis efforts.4–7 The reduction of the recorded prevalence can be attributed to the widespread availability of free multidrug therapy (MDT), along with a shortening of the standard treatment.8 The reported annual number of new cases has plateaued at 200 000–250 000 globally in the past decade; with 213 899 new diagnoses reported in 2015.1 2 This stagnation, and the fact that still about 10% of the new diagnoses occur in children, suggests ongoing leprosy transmission,4 7 while the continuing detection of patients with advanced disease indicates serious diagnostic delays.7 As a result, alternative control strategies are needed to interrupt transmission of Mycobacterium leprae and accelerate case detection.

The main risk factor for leprosy is prolonged close contact with an infectious patient.9 Early case detection and prompt treatment with MDT are the cornerstones of the WHO recommendations for leprosy control10 11 but solid evidence exists that post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) with single dose rifampicin (SDR) can reduce the risk of contacts to develop leprosy by 50–60% over the 2 years following SDR administration.12–15 Chemoprophylaxis has already been used in the 60s and 70s when weekly dapsone for 2–3 years was tested, an approach that proved too cumbersome to become widely implemented.16–21 Other trials used acedapsone every 10 weeks for 7 months.22 23 A meta-analysis of the dapsone studies showed their superiority over placebo with an overall reduction of the leprosy new case detection rate (NCDR) of 40% in contacts,16 17 20 while the NCDR reduction of acedapsone prophylaxis was 51%.13 22 23 In 1988, SDR chemoprophylaxis (25 mg/kg) was first studied in the Southern Marquesas Islands in a non-controlled trial.24 25 A follow-up survey 10 years later suggested a 70% effectiveness of chemoprophylaxis. However, over the same period a 50% reduction in the NCDR was observed in the non-treated population of French Polynesia. Therefore, the true effectiveness of SDR may have been 35–40%.26 In the mid-1990s, chemoprophylaxis was introduced on different Pacific islands where the leprosy NCDR had remained very high.27 Over two cycles, with a 1-year interval, 70% of the population was screened for leprosy and treated prophylactically. Healthy adults received rifampicin, ofloxacin and minocycline (ROM), while children under 15 years received SDR.28 In 1999, a substantial reduction in the NCDR was observed.27 Recent data indicate that transmission is ongoing.29 In 2000, a study using rifampicin only was initiated on five highly endemic Indonesian islands.14 The population was screened before the intervention and subsequently once a year for 3 years; two doses of rifampicin were administered to asymptomatic inhabitants with a 3.5 months interval, either in a ‘blanket’ approach where SDR was given to the entire population, or a ‘contact’ strategy in which SDR was only given to eligible household and neighbour contacts of patients with leprosy. The NCDR on the control island was 39/10 000. After 3 years, the cumulative NCDR in the blanket group was significantly lower (about 3 times), whereas no difference was found between the control group and the islands where SDR was given to contacts only.14

The COLEP trial in Bangladesh was a single-centre, double-blind, cluster-randomised, placebo-controlled study designed to determine the effectiveness of SDR in contacts and to identify the characteristics of contact groups most at risk of developing clinical leprosy.30 The overall risk reduction for contacts during the first 2 years after SDR administration was 57%. There was no further risk reduction beyond the 2 years12 and thereafter.31 The overall number needed to treat to prevent a single diagnosis of leprosy among contacts was 265 after 2 years and 297 after 4 years.12 The protective effect of SDR was highest in contact groups with the lowest a priori risk for leprosy: non-blood-related contacts, contacts of index patients with paucibacillary leprosy and social contacts.12 Importantly, childhood vaccination with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) also had a protective effect of nearly 60%, and previously immunised contacts appeared to benefit from an 80% protective effect.32

Considering all available evidence, it appears that chemoprophylaxis should target defined contact groups, but under certain conditions, mass administration may be warranted. High NCDRs, difficult geographical accessibility, insufficient availability healthcare services or a high level of stigma are reasons to prefer mass administration to targeted PEP.13 Two international expert meetings hosted by the Novartis Foundation in 2013 and 2014 and including physicians, epidemiologists and public health professionals, concluded that contact tracing followed by PEP for asymptomatic contacts has the potential to offer a degree of protection, across diverse settings, comparable to that reported in controlled trials.1 33

To accelerate the translation of the existing evidence into policy and motivate endemic countries to introduce chemoprophylaxis into their routine leprosy activities, the LPEP programme was designed. It aims to demonstrate the effectiveness and impact on case detection rates of contact tracing and screening combined with SDR PEP under routine programme conditions, across a diversity of health systems, national leprosy programmes and geographical characteristics, and to determine operational parameters.

Objectives

The LPEP programme aims to assess contact tracing and administration of SDR PEP implemented by national leprosy programmes with regard to:

Impact on the new case detection rate, measured through strengthened surveillance and reporting systems

Feasibility in diverse routine programme settings

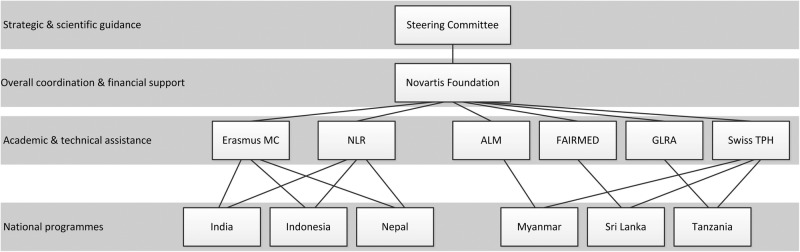

The LPEP programme provides a comprehensive package, including systematic contact tracing and screening for early case detection and PEP administration for asymptomatic contacts (figure 1). In addition, the programme also promotes capacity building for front-line leprosy workers to strengthen screening and diagnosis, and for surveillance system managers to improve data collection and reporting.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the impact of the LPEP programme on the transmission of Mycobacterium leprae. LPEP, leprosy post-exposure prophylaxis; MDT, multidrug therapy; SDR PEP, single dose rifampicin post-exposure prophylaxis.

Methods and analysis

Study coordination

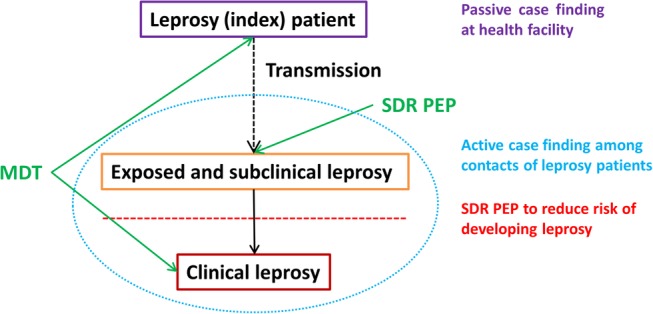

A steering committee of leprosy experts, policymakers, academic researchers, people affected by leprosy and the project partners (International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations (ILEP) members, national leprosy programmes and the Novartis Foundation) oversees the programme, advises on strategic and operational matters, establishes the dissemination strategy and reviews programme publications. The Novartis Foundation provides the overall coordination of the LPEP programme and ensures financial support. LPEP country protocol development, programme management and implementation at national level are handled by the national leprosy programmes supported by the respective ILEP partners. The Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH) and the Erasmus University's Medical Center (Erasmus MC) support the local programme protocol development, provide training and assist with the strengthening of surveillance systems operated by the national programmes. They further monitor adherence to protocol and data quality, coordinate data analysis and facilitate the dissemination of the study results. All in-country activities of the academic partners are closely coordinated with, and supported by, the respective ILEP partner and the national programme (figure 2). An annual meeting facilitates progress and review and exchange among the partners.

Figure 2.

Governance structure of the LPEP programme. ALM, American Leprosy Mission; Erasmus MC, Erasmus Medical Center; GLRA, German Leprosy and Tuberculosis Relief Association; ILEP, International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations; LPEP, leprosy post-exposure prophylaxis; NLR, Netherlands Leprosy Relief; Swiss TPH, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute.

Study areas

Participation in the LPEP programme was open to countries meeting the following criteria: (1) subnational administrative units (eg, districts) with a high NCDR, relatively easy access and a functioning leprosy control infrastructure, (2) capacity for routine contact tracing and screening in the local leprosy programme, (3) declared interest from the Ministry of Health and (4) commitment and resources to continue contact tracing and PEP after the conclusion of the LPEP programme. When selecting the countries, diversity in terms of geography and leprosy programme organisation was taken into account. Table 1 presents key leprosy indicators at baseline in the selected LPEP sites in India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Tanzania. Additional pilot sites are located in Brazil and Cambodia.

Table 1.

Key leprosy-related indicators in the areas where the LPEP programme is implemented (baseline as of 2013)

| Country | India | Indonesia |

Myanmar |

Nepal |

Sri Lanka |

Tanzania |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subnational area | Dadra & Nagar Haveli union territory | Sumenep district | Maluku Tenggara Barat (Lingat village) | Nyaung-U district | Myingyan district | Tharyar waddy district | Jhapa district | Morang district | Parsa district | Kalutara district | Puttalam district | Kilombero district | Liwale district | Nanyumbu district |

| Population (in thousands) | 374 | 1059 | 1.9 | 738 | 976 | 1110 | 813 | 965 | 601 | 1200 | 800 | 401 | 95 | 159 |

| NCDR (per 10 000) | 9.8 | 4.5 | NA* | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 5.8 | 6.7 |

| New cases of MB leprosy (%) | 23.1 | 75.8 | NA* | 68.9 | 75.3 | 67.5 | 57.2 | 47.8 | NA | 36.4 | 60.9 | 76.1 | 78.2 | 58.5 |

| New cases with G2D (%) | 0.0 | 9.5 | NA* | 6.8 | 19.5 | 14.9 | 2.2 | 7.1 | 1.6 | 5.5 | 13.0 | NA | 1.8 | 6.6 |

| New cases (%): | ||||||||||||||

| Females | 59.2 | 48.0 | NA* | 47.3 | 37.7 | 34.2 | 38.0 | 38.6 | NA | 44.2 | 41.3 | NA | 49.1 | 51.9 |

| Children | 26.1 | 10.9 | NA* | 2.7 | 3.9 | 7.0 | 4.8 | 11.7 | 8.9 | 6.7 | 9.8 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 8.5 |

*No data available due to absence of leprosy services in this isolated village, but a visiting health worker from district level reported 30 suspected patients with leprosy.

G2D, grade 2 disability; MB, multibacillary; NA, not available; NCDR, new case detection rate.

Study design

In agreement with its objectives; the LPEP programme is implemented under routine conditions rather than as a clinical trial. A general study protocol was prepared and served as the basis for the elaboration of national LPEP protocols tailored to the realities of each country. Patients with leprosy diagnosed <2 years prior to the start of the field work (retrospective index patients) and patients diagnosed during the programme period (3 years prospective index patients) are eligible for inclusion. These index patients have to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) confirmed leprosy diagnosis and being on MDT treatment for at least 4 weeks, (2) residency in an LPEP pilot area, (3) one or more contacts (as defined by the local definition of contacts, see table 2) and (4) willingness to disclose their disease status to the targeted contacts. All traced contacts are screened for signs of leprosy. Exclusion criteria for SDR administration are: (1) refusal to give informed consent, (2) age <2 or 6 years (country-specific age ranges are applied, see table 2), (3) pregnancy (PEP can be given after delivery), (4) rifampicin use in the past 2 years (eg, for tuberculosis (TB) or leprosy treatment, or preventively as a contact of another index patient), (5) history of liver or renal disorders (eg, jaundice), (6) leprosy disease, (7) signs and/or symptoms of leprosy until negative diagnosis, (8) signs and/or symptoms of TB until negative diagnosis (patients having any of the following symptoms are referred for full TB assessment: cough for more than 2 weeks, night sweats, unexplained fever, weight loss) and (9) known allergy to rifampicin.

Table 2.

LPEP modalities in the participating countries

| Activities | India | Indonesia | Myanmar | Nepal | Sri Lanka | Tanzania |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Routine contact tracing in the national programme | HH members and neighbours | HH members and neighbours | HH members | HH members and neighbours | not systematic | none |

| Contact definition in LPEP | HH members, neighbours and class fellows | HH members and neighbours | HH members and neighbours | HH members and neighbours | HH members | HH members |

| Estimated number of contacts per index patient | 20 | 50 | 20 | 30 | 5 | 5 |

| Screening period for LPEP | Retrospective contact tracing starting in 2013 | Contact tracing starting in 2015 | Retrospective contact tracing starting in 2014 | Retrospective contact tracing starting in 2014 | Retrospective contact tracing starting in 2015 | Retrospective contact tracing starting in 2014 |

| Responsible for contact tracing | Accredited social health activist, para medical worker, multipurpose health worker | Village midwife | Midwives, PHS2 or JLW; supported by (Assistant) LI | Leprosy focal person and female CHV | PHI | Trained VHW |

| Responsible for contact screening | Para medical worker and multipurpose health worker | Self-screening; Leprosy health worker at PHC and Village midwife | Midwives, PHS2 or JLW; supported by (Assistant) LI | Leprosy focal person and female CHV | MOH | VHW |

| Responsible for diagnosis | Doctor at PHC | Leprosy health worker at PHC | Midwives, PHS2 or JLW; supported by (Assistant) LI | Leprosy focal person/doctor | Dermatologist | Clinician |

| Responsible for SDR administration | Para medical worker and multipurpose health worker | Leprosy health worker at PHC | Midwives, PHS2 or JLW; supported by (Assistant) LI | Leprosy focal person and female CHV | MOH | VHW |

| Minimum Age for SDR | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 |

| Level of data entry | At district level | At district level | At national level | At district level | At district level | At district level |

CHV, community health volunteer; DTLC, district TB and leprosy coordinator; HH, household; JLW, junior leprosy worker; LI, leprosy inspector; LPEP, leprosy post-exposure prophylaxis; MOH, medical officer of health; PHC, primary health centre; PHS2, public health supervisor 2; PHI, public health inspector; PMW, para medical worker; VHW, voluntary health worker.

Table 2 presents the study modalities in the different countries. Leprosy services are integrated into primary healthcare services in all LPEP countries, with passive case detection as the core strategy of the routine leprosy programmes combined with contact tracing in all countries except Tanzania (see online supplementary annex 2). Focal persons for diagnosis of leprosy vary from non-clinician health professionals in Indonesia, Myanmar and Nepal, to trained clinicians in India, Sri Lanka and Tanzania. Notably, contact tracing, screening and diagnosis are all performed by different functions and persons in Sri Lanka, demanding particularly robust communication and information systems.

bmjopen-2016-013633supp_annex.pdf (209.9KB, pdf)

In most study areas the LPEP programme targets specific contact groups. Owing to high prevalence, its difficult access and the closed character of the community, a blanket approach is applied in a village on the Indonesian Selaru Island (Lingat) where all inhabitants are screened and PEP is administered to all asymptomatic individuals.

Sample size calculation

To establish a decreasing trend in the NCDR of 10–15% per year in every LPEP country, with sufficient statistical power (p=0.05), a logistic regression model suggests the enrolment of between 175 (decrease of 15% in NCDR) and 400 (decrease of 10% in NCDR) new index patients per year.

Data collection and monitoring

The data collection and reporting solutions for LPEP were developed or adapted by the technical partners in close collaboration with the national leprosy programmes and the in-country ILEP partners. To ensure the seamless integration of the LPEP programme into the national leprosy control programmes, existing data collection and reporting systems were assessed. The aim was to use the available structures wherever feasible and thereby to minimise duplication of data collection efforts between national programmes and LPEP. Supplementary LPEP forms were then developed to capture the not-routinely collected data. The minimally required LPEP indicators are listed in online supplementary annex 1. Sociodemographic information, leprosy classification and disability grade, disease history (mode of detection, start of treatment) and previous rifampicin use (apart from MDT) are recorded for all index patients. For contacts, data collection captures sociodemographic characteristics, relationship to the index patient, contact category (household, neighbour, social), BCG vaccination scar, outcome of the screening (signs of leprosy or TB) and SDR exclusion criteria. In addition, referrals and adverse events (AEs) following SDR PEP are documented (see Ethics section).

A programme-specific database is offered to participating countries but any locally developed database that fits the programme requirements is also accepted. For example in Sri Lanka, a locally developed MySQL database is used. Data entry is carried out continuously, either at national or district level; and database copies are regularly shared with the technical and ILEP partners for verification and interim analyses. Feasibility will be evaluated in terms of coverage (proportion of contacts traced, screened and receiving PEP, if eligible), required resources and coordination efforts. Effectiveness will be measured as the impact of the LPEP programme on the NCDR of the pilot areas.

In addition to the routine surveillance and programme-specific monitoring of the national programme, twice yearly monitoring visits are conducted by the technical and in-country ILEP partners to monitor protocol adherence, resolve operational questions and evaluate the quality of procedures and data. Data collection and monitoring will be maintained for 3 years.

Ethics

An expert meeting, involving both tuberculosis and leprosy experts, focused on the potential risk of promoting rifampicin resistance through the use of SDR in leprosy control. It concluded that current evidence suggests that the risk of emerging rifampicin resistance in M. tuberculosis is minimal, and that the benefit of reducing the leprosy NCDR largely outweighs that risk.34

The national leprosy programmes submitted the country-specific LPEP protocol and data collection instruments for review and approval to the relevant ethics committees. There was no need for ethical clearance in Indonesia as the country has already integrated the principle of PEP into its routine leprosy programme in several districts. In each of the participating countries, a designated national expert from the Ministry of Health acts as the principal investigator for the LPEP programme.

Informed consent is obtained from all index patients and contacts, either written or verbally, depending on local practices for comparable studies and as approved by the ethical committee. It contains information on possible side effects of SDR (ie, influenza-like syndromes and discolouration of urine) and details of how a leprosy expert can be contacted in case of AEs or other concerns. AEs are reported following national pharmacovigilance guidelines and using the LPEP AE Form, while referred for proper follow-up.

Discussion

The WHO global strategy for leprosy control 2011–2015 called for increased investments in operational research to support the overall aims of the global leprosy control programme, and to evaluate novel and promising interventions.10 11 Being an essential building block of various disease control and outbreak containment programmes, contact tracing and chemoprophylaxis have been identified as key factors to sustainably reduce the number of new patients and move towards M. leprae transmission interruption. The LPEP programme is designed to answer key questions regarding the implementation of chemoprophylaxis for leprosy control and to provide evidence for the feasibility and impact of contact tracing and PEP on the NCDR across a range of different health systems and levels of leprosy endemicity.

The LPEP programme is accompanied by ancillary studies. The cost-effectiveness study aims to measure the local costs associated with contact tracing and PEP and compare those to the costs of routine case detection and treatment. The acceptability and perception studies focus on knowledge and understanding of leprosy in communities where LPEP is implemented, on attitudes and behaviour towards persons affected by leprosy, and views of the proposed intervention among different stakeholders.

In Brazil and Cambodia, similar approaches, complementing the evidence from the LPEP programme, are tested. In Brazil, the government-funded ‘PEP-Hans’ project explores the administration of chemoprophylaxis and immunoprophylaxis (SDR and BCG), to about 20 contacts per index patient. PEP-Hans is implemented in 16 municipalities of Mato Grosso, Pernambuco and Tocantins states, and covers index patients diagnosed from 2015 to 2017. An estimated 850 index patients with 17 000 contacts will be included each year. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for SDR and BCG are aligned with the LPEP programme, as are the main variables for impact evaluation. Chemoprophylaxis and immunoprophylaxis cannot be co-administered since there is a minimum waiting time of 24 hours for BCG after SDR, and of 30 days for SDR after BCG. In Cambodia, the administration of SDR to household and neighbour contacts is evaluated within the ‘Retrospective Active Case Finding’ project started in 2011. Given the relatively low number of new patients with leprosy diagnosed in this country, the contacts of all patients diagnosed in an operational district since 2011 are traced, screened and managed in a single ‘drive’. This approach is repeated until all 31 high-priority operational districts have been covered. The project is implemented by a consortium involving the National Leprosy Elimination Programme, CIOMAL (International Committee of the Order of Malta for Leprosy Relief) and the Novartis Foundation.

Outlook

After 3 years of SDR administration to contacts of patients with leprosy, the full impact and feasibility of the intervention will start to emerge in 2019. Data will be analysed at country level, and pooled analyses will be conducted as far as differences in the epidemiology and set-up of national leprosy programmes allow.

The LPEP programme will help to translate the existing evidence on SDR PEP for reducing the risk of developing leprosy among contacts of patients with leprosy into routine action by providing solid data from a range of settings and conditions, established by national leprosy control programmes themselves. Participating countries will be in a good position to fully integrate contact tracing and SDR PEP into their national leprosy control strategies and expand the activities to additional areas in the country.

Dissemination of the results and lessons learnt from the LPEP programme will be carried out through publication in open access journals, as well as through reports and conference abstracts and presentations. The data will provide crucial guidance for Ministries of Health of all leprosy endemic countries interested in applying a similar approach. The results of the LPEP programme will also be of great value for global policymakers when deciding on resource allocation for the interruption of M. leprae transmission.

Footnotes

Contributors: LM, WvB, JHR, AC, BVP and AA designed the study. TB-J, PS, LM, WvB, JHR, AT, MB, AC, BVP, FM and AA supported the development of country-specific protocols, and coordinate and monitor the study implementation. TB-J, PS, MB and J-HR have drafted the manuscript. All authors have reviewed the draft manuscript, and have read and approved the final version. The LPEP study group ensures the scientific integrity of all aspects of the programme, and all LPEP study group members have received and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The LPEP programme is funded by the Novartis Foundation.

Competing interests: All co-authors are either staff of the Novartis Foundation or work as paid consultants for the programme described here.

Ethics approval: (1) The Institutional Human Ethical Committee of the National Institute of Epidemiology in India (NIE/IHEC/201407-01); (2) The Ethical Committee on Medical Research involving Human Participants at the Department of Health of the Ministry of Health in Myanmar (13/2014/1087); (3) The Ethical Review Board at the Nepal Health Research Council in Nepal (39/2015); (4) The Ethics Review Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Kelaniya in Sri Lanka (P/134/08/2015); and (5) The Ethical Committee at the National Institute for Medical Research of the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare in Tanzania (approval date: 4 May 2015).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Smith CS, Noordeen SK, Richardus JH et al. . A strategy to halt leprosy transmission. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:96–8. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70365-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Global leprosy update, 2014: need for early case detection. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2015;90:461–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Global leprosy update, 2013; reducing disease burden. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2014;89:389–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodrigues LC, Lockwood DNj. Leprosy now: epidemiology, progress, challenges, and research gaps. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:464–70. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70006-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burki T. Old problems still mar fight against ancient disease. Lancet 2009;373:287–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60083-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burki T. Fight against leprosy no longer about the numbers. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:74 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70015-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith WC, van Brakel W, Gillis T et al. . The missing millions: a threat to the elimination of leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9:e0003658 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noordeen SK. History of chemotherapy of leprosy. Clin Dermatol 2016;34:32–6. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2015.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Beers SM, Hatta M, Klatser PR. Patient contact is the major determinant in incident leprosy: implications for future control. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 1999;67:119–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. Enhanced global strategy for further reducing the disease burden due to leprosy (Plan Period: 2011–2015). New Delhi: South-East Asia Region, 2009. [PubMed]

- 11.WHO. Enhanced global strategy for further reducing the disase burden due to leprosy (2011–2015) Operational guidelines (updated) New Delhi: South-East Asia Region, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moet FJ, Pahan D, Oskam L et al. . Effectiveness of single dose rifampicin in preventing leprosy in close contacts of patients with newly diagnosed leprosy: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008;336:761–4. 10.1136/bmj.39500.885752.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reveiz L, Buendía JA, Téllez D. Chemoprophylaxis in contacts of patients with leprosy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2009;26:341–9. 10.1590/S1020-49892009001000009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakker MI, Hatta M, Kwenang A et al. . Prevention of leprosy using rifampicin as chemoprophylaxis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005;72:443–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith CM, Smith WC. Chemoprophylaxis is effective in the prevention of leprosy in endemic countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2000;41:137–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wardekar RV. DDS prophylaxis against leprosy. Lepr India 1967;39:155–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noordeen SK. Chemoprophylaxis in leprosy. Lepr India 1969;41:247–54. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noordeen SK, Neelan PN. Chemoprophylaxis among contacts of non-lepromatous leprosy. Lepr India 1976;48:635–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noordeen SK. Long term effects of chemoprophylaxis among contacts of lepromatous cases. Results of 8 1/2 years follow-up. Lepr India 1977;49:504–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noordeen SK, Neelan PN. Extended studies on chemoprophylaxis against leprosy. Indian J Med Res 1978;67:515–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otsyula Y, Ibworo C, Chum HJ. Four years’ experience with dapsone as prophylaxis against leprosy. Lepr Rev 1971;42:98–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neelan PN, Noordeen SK, Sivaprasad N. Chemoprophylaxis against leprosy with acedapsone. Indian J Med Res 1983;78:307–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neelan PN, Sirumban P, Sivaprasad N. Limited duration acedapsone prophylaxis in leprosy. Indian J Lepr 1986;58:251–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cartel JL, Chanteau S, Moulia-Pelat JP et al. . Chemoprophylaxis of leprosy with a single dose of 25 mg per kg rifampin in the southern Marquesas; results after four years. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 1992;60:416–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cartel JL, Chanteau S, Boutin JP et al. . Implementation of chemoprophylaxis of leprosy in the Southern Marquesas with a single dose of 25 mg per kg rifampin. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 1989;57:810–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen LN, Cartel JL, Grosset JH. Chemoprophylaxis of leprosy in the southern Marquesas with a single 25 mg/kg dose of rifampicin. Results after 10 years. Lepr Rev 2000;71:S33–5; discussion S35–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanc LJ. Summary of leprosy chemoprophylaxis programs in the Western Pacific Region. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 1999;67:S30–31. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diletto C, Blanc L, Levy L. Leprosy chemoprophylaxis in Micronesia. Lepr Rev 2000;71:S21–3; discussion S24–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO. Epidemiological review of leprosy in the Western Pacific Region, 2008–2010. Manila: Western Pacific Region, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moet FJ, Oskam L, Faber R et al. . A study on transmission and a trial of chemoprophylaxis in contacts of leprosy patients: design, methodology and recruitment findings of COLEP. Lepr Rev 2004;75:376–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feenstra SG, Pahan D, Moet FJ et al. . Patient-related factors predicting the effectiveness of rifampicin chemoprophylaxis in contacts: 6 year follow-up of the COLEP cohort in Bangladesh. Lepr Rev 2012;83:292–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuring RP, Richardus JH, Pahan D et al. . Protective effect of the combination BCG vaccination and rifampicin prophylaxis in leprosy prevention. Vaccine 2009;27:7125–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith WC, Aerts A. Role of contact tracing and prevention strategies in the interruption of leprosy transmission. Lepr Rev 2014;85:2–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mieras L, Anthony R, van Brakel W et al. . Negligible risk of inducing resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis with single-dose rifampicin as post-exposure prophylaxis for leprosy. Infect Dis Poverty 2016;5:1–5. 10.1186/s40249-016-0140-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013633supp_annex.pdf (209.9KB, pdf)