Figure 2.

Experiment 2

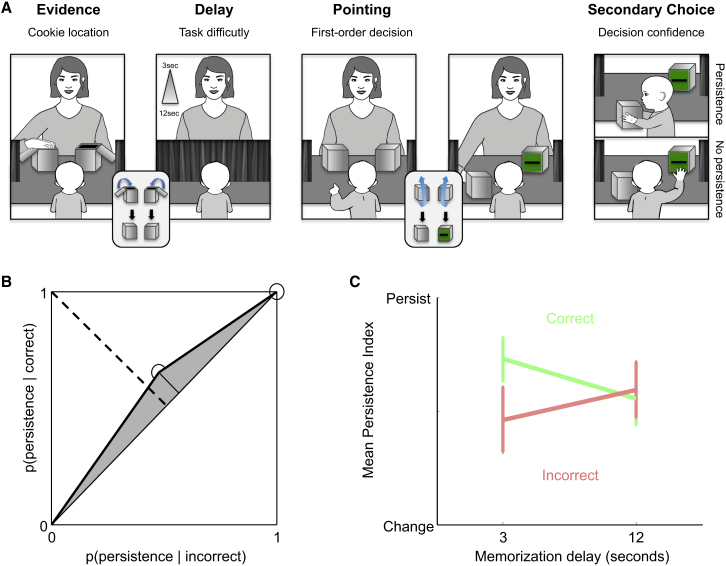

(A) Experimental design. The two boxes contained a lid, which could only be opened by an adult. Although one of them had a slit such that infants were able to directly reach for its content (unsealed box), there was no slit in the other box, rendering its content unreachable without the help of an adult (sealed box). Importantly, both boxes looked identical from the infants’ point of view, such that they could not know which box they were selecting (sealed versus unsealed box). During the familiarization phase (four trials), infants saw the experimenter hide a biscuit in one of two boxes. The experimenter then asked them to point to indicate where they remembered the biscuit to be. As soon as infants produced a pointing response, the selected box was pushed forward. During the first two trials, the biscuit was hidden in the unsealed box, so infants could directly recover it. During the last two trials, the biscuit was hidden in the sealed box, so as to teach infants to ask their caregiver to open it for them. The test phase (eight trials) was similar to the familiarization phase except for two elements. First, a variable memorization delay (3 or 12 s) was introduced. Second, the biscuits were now hidden half of the time in the unsealed box and the other half in the sealed box. Importantly, infants selected the sealed and unsealed boxes equally often (t(21) = 0.3; p > 0.7), showing that they could not discriminate the two boxes before pointing. Selection of the sealed box forced infants to either confirm their initial choice by asking their caregiver to open it or invalidate their initial choice by turning to the alternative box, whose content was directly reachable.

(B) Mean type 2 ROC curve. Individual type 2 ROC curves were constructed by plotting the probability of producing one type of secondary response for correct trials against the probability of producing the same type of secondary response for incorrect trials.

(C) Relationship between persistence and accuracy depending on task difficulty. A persistence index was obtained for each subject by coding secondary actions in a binary fashion, with zeros corresponding to changes of mind (i.e., no persistence) and ones corresponding to asking for help (i.e., persistence). Persistence indices were then averaged separately for correct and incorrect trials, per levels of difficulty, for each participant. Error bars show SEMs.

See also Figure S2.