Abstract

Objective:

To identify relationships between insulin resistance (IR) and mitochondrial respiration in perinatally HIV-infected youth.

Design:

Case–control study.

Methods:

Mitochondrial respiration was assessed in perinatally HIV-infected youth in Tanner stages 2–5, 25 youth with IR (IR+) and 50 without IR (IR−) who were enrolled in the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study. IR was defined as a homeostatic model of assessment for IR value at least 4.0. A novel, high-throughput oximetry method was used to evaluate cellular respiration in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Unadjusted and adjusted differences in mitochondrial respiration markers between IR+ and IR− were evaluated, as were correlations between mitochondrial respiration markers and biochemical measurements.

Results:

IR+ and IR− youth were similar on age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Mean age was 16.5 and 15.6 years in IR+ and IR−, respectively. The IR+ group had significantly higher mean BMI and metabolic analytes (fasting glucose, insulin, cholesterol, triglycerides, and venous lactate and pyruvate) compared with the IR−. Mitochondrial respiration markers were, on average, lower in the IR+ compared with IR−, including basal respiration (417.5 vs. 597.5 pmol, P = 0.074), ATP production (11 513 vs. 15 202 pmol, P = 0.078), proton leak (584.6 vs. 790.0 pmol, P = 0.033), maximal respiration (1815 vs. 2399 pmol, P = 0.025), and spare respiration capacity (1162 vs. 2017 pmol, P = 0.032). Nonmitochondrial respiration did not differ by IR status. The results did not change when adjusted for age.

Conclusion:

HIV-infected youth with IR have lower mitochondrial respiration markers when compared to youth without IR. Disordered mitochondrial respiration may be a potential mechanism for IR in this population.

Keywords: children, diabetes, HIV, insulin resistance, mitochondria

Introduction

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has been effective in controlling disease progression and extending life for HIV-infected patients but is also coupled with emerging and progressive longer term complications. Insulin resistance (IR) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are common among adults infected with HIV [1]. IR, a recognized precondition to T2DM, is also a concern in youth who are perinatally infected with HIV (pHIV), in which the prevalence is estimated to be between 15 and 52% [2,3].

The exact cause of IR in the setting of HIV is unknown, although mitochondrial dysfunction may play a role as is found in HIV-uninfected patients [4]. Mitochondria produce energy from fatty acids or glucose via oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). When OXPHOS is altered or dysfunctional, oxygen consumption is reduced and reactive oxygen species (ROS)/oxidative stress ensues leading to altered ATP/ADP ratios [10]. Clinically, direct inhibition of OXPHOS in muscle cells results in increased glucose uptake and lactate production, reduced glycogen synthesis and lipid and glucose oxidation, and unchanged lipid uptake [5]. These metabolic changes that result from mitochondrial dysfunction predispose to IR and T2DM.

In HIV infection, mitochondrial abnormalities associated with ART have been previously summarized [6–9]. Biomedical literature indicates that HIV itself and cART affect mitochondrial function via an array of mechanisms, including direct increases in ROS, decreases in ATP levels, and alterations in mitochondrial respiration (oxygen consumption) [6–9].

There are limited reports on the relationship of mitochondrial function and IR in HIV-infected youth [3,10]. Mitochondria play an integral role in cellular respiration, the biochemical processes that convert nutrients into usable energy (ATP) through the utilization of oxygen. In this case–control study, we characterize the phases of mitochondrial cellular respiration in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from pHIV children and determine the relationship between mitochondrial respiratory function and IR. The novelty of our study lies in the use of a high-throughput platform to assess cellular oxygen consumption among pHIV youth with and without IR.

Methods and materials

Study population

The Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS)-Adolescent Master Protocol (AMP) (https://phacsstudy.org/About-Us/Active-Protocols) enrolled 451 youth with pHIV who were 7–16 years of age from 2007 to 2009 from 15 study sites in the United States, including Puerto Rico. The PHACS-AMP is an ongoing, prospective study evaluating long-term effects of HIV infection and antiretrovirals in youth with perinatally acquired HIV infection. From these 451 pHIV youth, 361 were enrolled in a mitochondrial substudy from 2010 to 2015 (NIH R01 NR012885; M.G. and T.L.M., principal investigators). Youth were excluded from enrolling in the mitochondrial substudy if they had any known mitochondrial abnormality, Type I diabetes mellitus, liver dysfunction (including hepatitis B or C), or other conditions known to affect mitochondrial function or lactate levels (acute infection, malignancy, and ischemic condition).

Information was obtained on age, sex, self-reported race/ethnicity, and at yearly visit anthropometrics, and clinical, laboratory, and body composition assessments at predetermined intervals. Blood samples including PBMCs were also collected and stored for future studies in the PHACS central repository. Mitochondrial markers were measured in those enrolled in the mitochondrial substudy. IR was defined as a homeostasis model assessment IR (HOMA-IR) score at least 4.0 (IR+ cases) in our pubertal or postpubertal sample [2].

For this cross-sectional study of IR and mitochondrial respiration, we selected youth at the first mitochondrial substudy visit who were at Tanner stage 2–5. We selected all 25 pHIV youth with IR, and 50 pHIV who were randomly selected from the youth without IR. Ultimately, analysis was conducted on 22 IR+ and 44 IR− youth who had an adequate sample of PBMCs.

Clinical evaluation

History of antiretroviral use (past, current, and lifetime duration) was collected, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV clinical classification and nadir CD4+ cell count as well as current CD4+ cell count [11]. Tanner stage was determined by visual inspection. Weight and standing height were measured by standardized procedures [12]. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height2 (m2) [13]. Waist circumference was measured using a nonstretchable plastic tape measure at the navel at the end of gentle exhalation [12]. Waist-to-hip ratio was calculated. Weight, height, and BMI were standardized for age and sex using CDC-derived percentages and z-scores [13].

Laboratory evaluation

Blood samples were collected after a fast of at least 8 h to measure glucose, insulin, and lipids (total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides) at each site. Serum specimens were separated within 24 h of the draw and aliquoted as per protocol, labeled, and frozen at −70 °C. Glucose and insulin were measured at the Diabetes Research Institute Clinical Chemistry Laboratory at the University of Miami on a Cobas 6000 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) using the manufacturer's reagents and procedures. To quantify IR from fasting glucose and insulin measurements, HOMA-IR was calculated as [fasting insulin (μU/ml) × fasting glucose (mmol/l)/22.5].

Lactate and pyruvate samples were collected in chilled sodium fluoride-containing or potassium oxalate–containing tubes. Patients did not clench fists before or during the procedure, tourniquets were not used if possible, and the samples were processed within 30 min of collection. Abnormal lactate was defined as any level more than 2.0 mmol/l. If the lactate was more than 2.0 mmol/l, but the lactate/pyruvate ratio was 20 or less, repeat lactate/pyruvate measurements were done paying careful attention to blood-drawing technique.

Blood was collected in two EDTA tubes and processed within 2 h of the draw by separating PBMCs by Ficoll-Paque density gradient separation (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) in accordance with AIDS Clinical Trial Group guidelines [14]. Cells were viably cryopreserved at a concentration of 5 million cells/0.5-ml aliquots and stored at −140 °C at each site. Shipping occurred bi-monthly to the repository at Fisher Bioservices (Rockville, Maryland, USA). PBMCs were shipped quarterly to the University of Hawaii on dry ice by Fisher Bioservices and stored in liquid nitrogen at the University of Hawaii.

Mitochondrial cellular respiration and Mito Stress Test

Cellular respiration of PBMCs was assessed by the Seahorse XF24 (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, Massachusetts, USA). The Seahorse XF24 is a high-throughput oximetry platform to simultaneously measure oxygen consumption and extracellular acidification rates in real time. A Mito Stress Test uses additional reagents that can be introduced into the system to produce a distinctive trace that evaluates mitochondrial function by shutting down each of the complexes backwards in the electron transport chain (ETC). The areas under the curve from those individual traces can be integrated to determine the amount of basal respiration, ATP turnover, proton leak, maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, and nonmitochondrial respiration (Seahorse Bioscience; http://www.seahorsebio.com/resources/downloads/mito-stress.pdf).

The Mito Stress Test was performed with guidance from Hill et al.[15]. Cell viability was first determined using AOPI (acridine orange/propidium iodide) and PBMCs were seeded at a density of 5.0 × 105 cells per well in duplicate on cell culture plates treated with poly-l-lysine and allowed to settle and attach. Cell viability was 90–95%. Although the cells were adhering, the sensor cartridge ports were loaded with Mito Stress Test drug reagents oligomycin in port A, 2-[[4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl]hydrazinylidene]propanedinitrile] (FCCP) in port B, and a rotenone and antimycin A cocktail in port C. Drugs were solubilized in dimethylsulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and prepared at working concentrations in running media [XF Media (Seahorse Bioscience), modified with 25 mmol/l glucose (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mmol/l sodium pyruvate (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA) at pH 7.4, warmed to 37 °C] at final concentrations of 1.5 μmol/l for oligomycin, rotenone, and antimycin A, and at 2.0 μmol/l for FCCP. The sensor cartridge was placed in the Seahorse XF24 analyzer and allowed to calibrate and equilibrate. The cell culture plate was then inserted into the analyzer and programed to ensure a homogeneous environment. For each phase, measurements were performed in triplicate, totaling 12 points per trace.

The area under the curve was calculated from the trace for all respiratory parameters with the area under the first three points for basal respiration, points four to six for proton leak, points seven to nine for maximal respiration, the difference between basal and proton leak for ATP production, the difference between maximal and basal respiration for spare respiratory capacity, and from time zero through 110 min at point 12 as nonmitochondrial respiration. Negative plate controls were utilized to remove background interferences. THP-1 cells (a generous gift from Dr Peter Hoffmann at the University of Hawaii) were used at passage 4 for positive plate-to-plate controls, to verify assay reproducibility.

Data analysis

Comparison of demographic, metabolic, and mitochondrial parameters between those IR+ and IR− were performed using Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Using general linear models, we evaluated differences in respiration by IR status, unadjusted and adjusted for age. Spearman correlations were performed to evaluate associations between two continuous variables. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Participant characteristics

There were no differences between the groups in terms of sex, race/ethnicity, Tanner stage, CDC class, CD4+ cell count, HIV viral load, and current antiretroviral regimen. The median ages of the IR+ and IR− groups were 16.5 and 15.6 years (P = 0.104), and the majority of youth in both groups were Tanner 5 (76 and 58%, respectively) (Table 1). IR+ youth were significantly heavier (weight z-score 0.78 vs. 0.17 SD), had a greater BMI z-score (1.11 vs. 0.18 SD), and a higher waist-to-hip ratio (0.92 vs. 0.86) compared with the IR− group. The treatment regimens were similar between the groups with the majority of patients receiving cART with a protease inhibitor regimen. IR+ youth had higher levels of glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides (Table 2). Ever use of specific antiretroviral medications by IR status was not different between IR+ and IR− groups (Table 3).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics by insulin resistance status of youth.

| Characteristic | N (IR−/IR+) | IR− | IR+ | P valuea |

| Age (year) [median (IQR)] | 50/25 | 15.6 (13.0, 17.0) | 16.5 (14.8, 18.0) | 0.104 |

| Sex [female, N, (%)] | 50/25 | 25 (50) | 10 (40) | 0.468 |

| Race/ethnicity [N, (%)] | 50/25 | 1.00 | ||

| Hispanic | 13 (26) | 7 (28) | ||

| Black non-Hispanic | 36 (72) | 17 (68) | ||

| White/other non-Hispanic | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | ||

| Tanner stage [N (%)] | 50/25 | 0.521 | ||

| 2 | 8 (16) | 2 (8) | ||

| 3 | 5 (10) | 1 (4) | ||

| 4 | 8 (16) | 3 (12) | ||

| 5 | 29 (58) | 19 (76) | ||

| CDC class [N (%)] | 50/25 | 0.339 | ||

| A – mildly symptomatic | 10 (20) | 7 (28) | ||

| B – moderately symptomatic | 17 (34) | 12 (48) | ||

| C – severely symptomatic | 13 (26) | 4 (16) | ||

| N – not symptomatic | 10 (20) | 2 (8) | ||

| CD4+ cell count (cells/μl) [median (IQR)] | 44/24 | 687 (475, 851) | 574 (447, 899) | 0.379 |

| Nadir CD4+ cell count (cells/μl) [median (IQR)] | 50/25 | 339 (228, 540) | 215 (57, 442) | 0.042* |

| Current antiretroviral regimen [N (%)]b | 50/25 | 0.971 | ||

| cART with PI | 31 (62) | 17 (68) | ||

| cART without PI | 9 (18) | 4 (16) | ||

| Non-cART antiretroviral drugs | 4 (8) | 1 (4) | ||

| Not on antiretroviral drugs | 5 (10) | 2 (8) | ||

| Weight z-score [median (IQR)] | 50/23 | 0.17 (−0.52, 0.70) | 0.78 (0.28, 1.53) | 0.009** |

| Height z-score [median (IQR)] | 50/23 | −0.05 (−1.17, 0.59) | −0.41 (−1.51, 0.41) | 0.416 |

| BMI z-score [median (IQR)] | 50/23 | 0.18 (−0.44, 0.75) | 1.11 (0.57, 1.87) | <0.001*** |

| Waist-to-hip ratio [median (IQR)] | 49/21 | 0.86 (0.82, 0.91) | 0.92 (0.87, 1.0) | 0.015* |

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; cART, combined antiretroviral therapy; PI, protease inhibitor.

aWilcoxon Rank Sum test Fisher's exact Test/Kruskal Wallis test was used for categorical analyses was used for statistical analyses for continuous variables.

bFrequencies may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

*P ≤ 0.05.

**P ≤ 0.01.

***P ≤ 0.001.

Table 2.

Metabolic parameters in perinatally HIV-infected youth by insulin resistance status.

| Characteristic | N (IR−/IR+) | IR− [median (IQR)] | IR+ [median (IQR)] | P value |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 50/25 | 85 (80, 89) | 88 (84, 93) | 0.007** |

| Fasting Insulin (μU/ml) | 50/25 | 10.9 (6.9, 13.5) | 24.7 (22.4, 32.2) | <0.001*** |

| HOMA-IR | 50/25 | 2.3 (1.4, 2.8) | 5.9 (4.6, 7.4) | <0.001*** |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 49/25 | 153 (129, 172) | 182 (151, 198) | 0.012* |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 49/25 | 79 (54, 98) | 110 (88, 179) | <0.001*** |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 49/25 | 86 (73, 100) | 101 (68, 126) | 0.078 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 49/25 | 50 (41, 58) | 49 (43, 56) | 0.923 |

Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used for statistical analyses. HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; IR, insulin resistance.

*P ≤ 0.05.

**P ≤ 0.01.

***P ≤ 0.001.

Table 3.

Ever use of specific antiretroviral medications by insulin resistance status.

| Characteristic | HOMA-IR trigger status | ||||

| Yes (N = 25) | No (N = 50) | Total (N = 75) | P value* | ||

| HAART ever use | No | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 0.550 |

| Yes | 25 (100%) | 48 (96%) | 73 (97%) | ||

| Regimen includes PI + RTV or KAL ever use | No | 6 (24%) | 9 (18%) | 15 (20%) | 0.553 |

| Yes | 19 (76%) | 41 (82%) | 60 (80%) | ||

| d4T ever use | No | 3 (12%) | 13 (26%) | 16 (21%) | 0.235 |

| Yes | 22 (88%) | 37 (74%) | 59 (79%) | ||

| TDF ever use | No | 10 (40%) | 27 (54%) | 37 (49%) | 0.329 |

| Yes | 15 (60%) | 23 (46%) | 38 (51%) | ||

| ZDV ever use | No | 3 (12%) | 5 (10%) | 8 (11%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 22 (88%) | 45 (90%) | 67 (89%) | ||

| 3TC ever use | No | 1 (4%) | 5 (10%) | 6 (8%) | 0.657 |

| Yes | 24 (96%) | 45 (90%) | 69 (92%) | ||

| NVP ever use | No | 12 (48%) | 29 (58%) | 41 (55%) | 0.466 |

| Yes | 13 (52%) | 21 (42%) | 34 (45%) | ||

| ABC ever use | No | 15 (60%) | 27 (54%) | 42 (56%) | 0.805 |

| Yes | 10 (40%) | 23 (46%) | 33 (44%) | ||

| DDI ever use | No | 5 (20%) | 18 (36%) | 23 (31%) | 0.191 |

| Yes | 20 (80%) | 32 (64%) | 52 (69%) | ||

| RTV ever use | No | 7 (28%) | 11 (22%) | 18 (24%) | 0.578 |

| Yes | 18 (72%) | 39 (78%) | 57 (76%) | ||

| ATV ever use | No | 22 (88%) | 39 (78%) | 61 (81%) | 0.361 |

| Yes | 3 (12%) | 11 (22%) | 14 (19%) | ||

| EFV ever use | No | 13 (52%) | 27 (54%) | 40 (53%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 12 (48%) | 23 (46%) | 35 (47%) | ||

Fisher's Exact test/Kruskal Wallis test was used for categorical analyses. 3TC, lamivudine; ABC, abacavir; ATV, atazanavir; d4T, stavudine; DDI, didanosine; EFV, efavirenz; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; KAL, Iopinavir/ritonavir; NVP, nevirapine; PI, protease inhibitor; RTV, ritonavir; TDF, tenofovir; ZDV, zidovudine.

*P ≤ 0.05.

Mitochondrial respiration

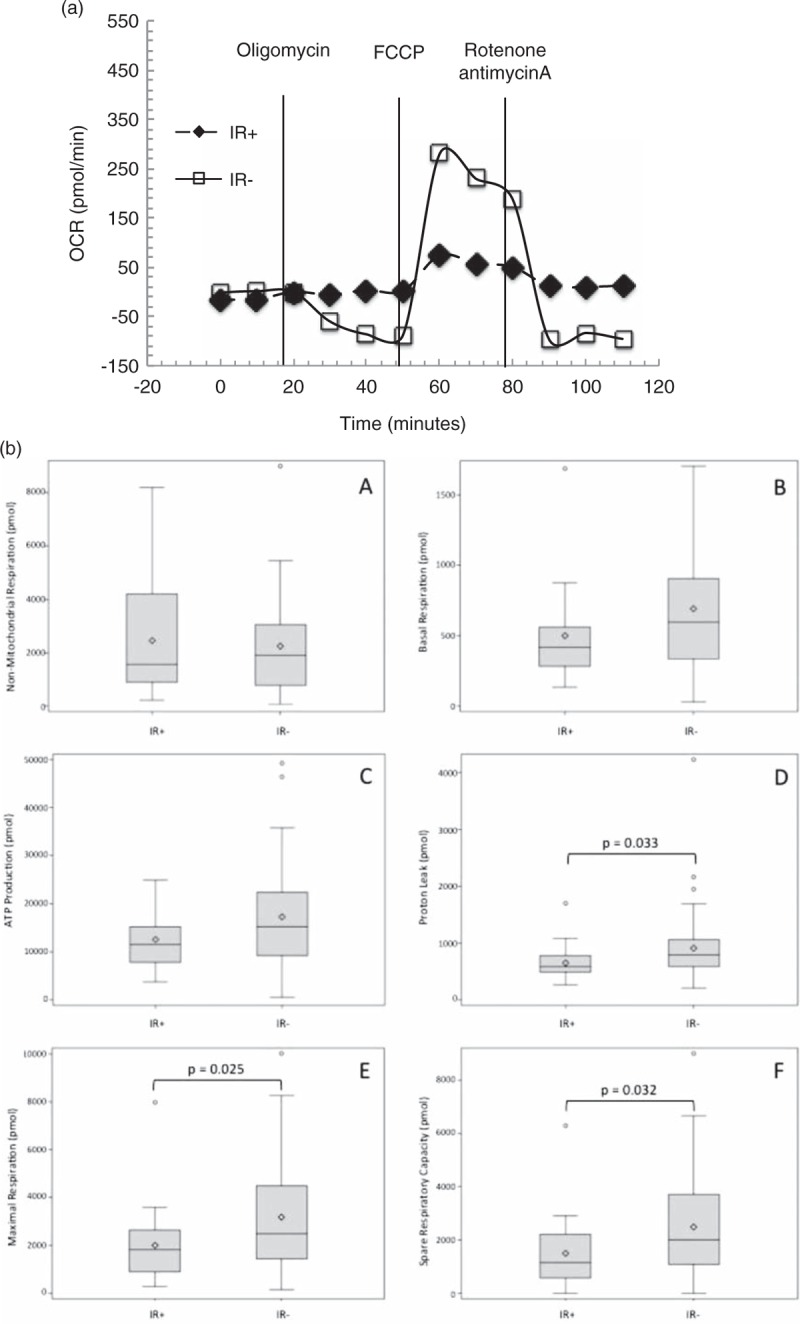

Representative traces from an IR+ and an IR− patient are shown in Fig. 1a. Among IR+ patients, there was very little variability (peaks and troughs) after injection of oligomycin, FCCP, rotenone, and antimycin A (data not shown). However, the representative trace for the IR− patient had greater variability in oxygen consumption after each injection as shown.

Fig. 1.

(a) Representative respiration curve of an insulin resistant (IR+, closed diamonds) and a non–insulin resistant (IR−, open squares) patients.

Vertical lines indicate injections of inhibitors (oligomycin-ATP coupler, 2-[[4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl]hydrazinylidene]propanedinitrile]-electron transport chain accelerator, and rotenone and antimycin A-mitochondrial inhibitors). Samples were assayed in duplicate for every time point. Measurements 0–20 min were used to calculate basal respiration, 30–50 min in the calculation of proton leak and ATP production, 60–80 min to calculate maximal respiration and spare respiratory capacity, and 90–110 min to calculate nonmitochondrial respiration. The IR+ youth have very little changes in oxygen consumption, whereas the IR− youth have notable changes in oxygen consumption. OCR, oxygen consumption rate. (b) Differences in mitochondrial respiratory parameters in 22 with insulin resistant and 44 non–insulin resistant youth. Area under the curve is calculated using the respiration curves and integrating under the curves before and after inhibitor injection. There was no difference in nonmitochondrial respiration between groups (A). Differences in basal respiration (B) and ATP production (C) approached significance. Significant differences between IR+ and IR− were observed in proton leak (D), maximal respiration (E), and spare respiratory capacity (F). AUC, area under the curve.

Comparisons of mitochondrial respiratory components between groups are shown in Table 4 and Fig. 1b. IR+ youth had higher venous lactate and pyruvate than IR− youth. The IR+ youth had significantly lower levels of proton leak (P = 0.033), maximal respiration (P = 0.025), and spare respiratory capacity (P = 0.032). Differences in basal respiration (P = 0.074) and ATP production (P = 0.078) between groups were borderline significant, whereas nonmitochondrial respiration was similar (P = 0.881). The results did not change when adjusted for age.

Table 4.

Mitochondrial respiratory characteristics in perinatally HIV-infected youth by insulin resistance status.

| Characteristic | N (IR+/IR−) | IR− [median (IQR)] | IR+ [median (IQR)] | P value |

| Venous lactate (mmol/l) | 46/24 | 1.10 (0.8, 1.2) | 1.6 (1.2, 1.9) | <0.001* |

| Venous pyruvate (mmol/l) | 45/24 | 0.09 (0.06, 0.11) | 0.12 (0.09, 0.17) | 0.003** |

| Basal respiration (pmol) | 44/22 | 597.5 (335, 906) | 417.5 (282, 561) | 0.074 |

| ATP production (pmol) | 44/22 | 15 202.1 (9164, 22 450) | 11 513.3 (7761, 15 220) | 0.078 |

| Proton leak (pmol) | 44/22 | 790.0 (590, 1058) | 584.6 (487, 782) | 0.033*** |

| Maximal respiration (pmol) | 44/22 | 2499.2 (1447, 4493) | 1815.8 (889, 2652) | 0.025*** |

| Spare respiratory capacity (pmol) | 44/22 | 2017.1 (1089, 3719) | 1162.5 (586, 2225) | 0.032*** |

| Nonmitochondrial respiration (pmol) | 44/22 | 1912.1 (786, 3056) | 1562.9 (895, 4216) | 0.881 |

Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used for statistical analyses.

*P ≤ 0.001.

**P ≤ 0.01.

***P ≤ 0.05.

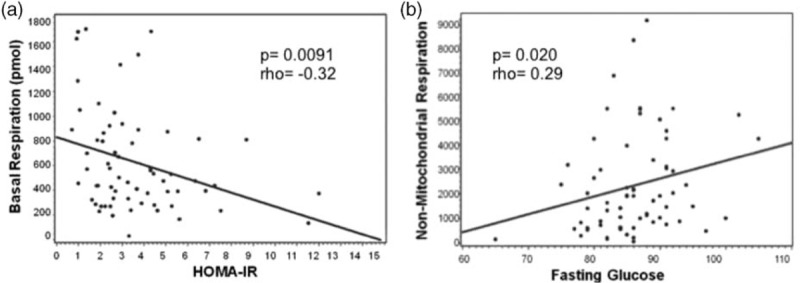

For the entire cohort (IR+ and IR−) mitochondrial respiratory parameters [basal respiration (r = −0.32; P = 0.0091), ATP (r = −0.346; P = 0.0044), proton leak (r = −0.347; P = 0.0043), maximal respiration (r = −0.347; P = 0.0043), and spare respiratory capacity (r = −0.334; P = 0.0062)] were negatively correlated with HOMA-IR. Figure 2 shows the negative relationship between HOMA-IR and basal respiration and positive relationship between glucose and nonmitochondrial respiration. Respiratory parameters [basal respiration (r = −0.252; P = 0.043), ATP production (r = −0.318; P = 0.010), proton leak (r = −0.308; P = 0.013), maximal respiration (r = −0.340; P = 0.0056), and spare respiratory capacity (r = −0.342; P = 0.0054)] were also negatively associated with LDL. Maximal respiration (r = −0.357; P = 0.013) and spare respiratory capacity (r = −0.357; P = 0.0047) were negatively correlated with waist-to-hip ratio. No other metabolic parameters were associated with respiration parameters.

Fig. 2.

Metabolic correlations associated with mitochondrial respiratory parameters.

Data represented are from perinatally HIV-infected youth (N = 66). (a) Relationship between basal respiration and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance with and without IR. An inverse relationship exists between basal respiration and insulin-resistant status as determined by homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (P value = 0.0091, rho = −0.32). (b) Relationship between nonmitochondrial respiration and fasting glucose. A positive correlation exists between fasting glucose and nonmitochondrial respiration (P value = 0.02, rho = 0.29).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated mitochondrial respiration in perinatally HIV-infected youth with IR and without IR who were well matched on demographics, pubertal development, current antiretroviral exposures, and HIV disease severity. We found that measures of multiple components of mitochondrial respiration were lower in those youth with IR compared with those without IR. Nonmitochondrial respiration was similar between groups. This is one of the first studies in perinatally HIV-infected youth that has associated impaired mitochondrial respiration with IR.

Mitochondrial respiratory function was different between the groups. Inhibitors that were used in this study shut down complexes starting at the end of the ETC working toward complex I. In doing so, the amount of oxygen consumed through these processes could be assessed by evaluating processes between each complex. Nonmitochondrial respiration results after completely shutting down the ETC with the rotenone and antimycin A cocktail. Nonmitochondrial respiration accounts for any other oxygen-consuming processes that are occurring and that are not conducted by ETC. Similar studies in non-HIV human PBMCs have been done in isolated human monocytes, lymphocytes, and platelets and showed that each had a distinct bioenergetics profile [16]. Limitations of this methodology are that the duration of cryopreservation of the cells and that cryopreservation/viability should be comparable among samples [17].

The positive correlation observed between nonmitochondrial respiration and fasting glucose suggests that there is damage to the ETC. FCCP is the optimal uncoupling agent from which maximal capacity and the spare respiratory capacity are calculated. The maximal capacity is the maximum total amount of energy that can be produced, whereas the spare respiratory capacity is indicative of the amount of energy that can be produced in a fight-or-flight response. The increase in nonmitochondrial respiration suggests that the integrity of the ETC is damaged and/or that there is substrate unavailability.

Following injection of oligomycin, ATP production, and proton leak are calculated. This decrease in ATP production in IR+ compared with IR− patients is also suggestive of damaged ETC integrity and substrate unavailability. Reasonably, proton leak was minimal as the peaks and troughs in the IR+ group were not highly variable. Proton leak in the IR− group was higher than in the IR+ group, which is often observed due to the high production of ATP leading to electron slippage; however, elevation in proton leak can be indicative of compromised ETC and ruptured membranes.

Finally, basal respiration reflects the amount of oxygen consumed at rest. A trend of lowered basal respiration in the IR+ suggests an adaptive response and/or a reduction of energy production through OXPHOS. Further insight into these differences is discussed by Hill et al.[18]. Reportedly, insulin-resistant/diabetic individuals have higher levels of oxidation products than those without these metabolic abnormalities [14,19]. This study is unlike that of Hartman et al. in which mitochondrial function was evaluated in T2DM and nondiabetic patients. This study identified significant differences in basal respiration, ATP production, and maximal respiration between the IR– and IR+ [20].

Collectively, these findings point to a disruption in utilization of nutrients to produce energy in our IR+ cohort. This suggests dysfunctional mitochondria and/or a breakdown in the hepatic-β-cell feedback loop both of which can account for the differences in glucose, insulin, and mitochondrial respiration. A significant positive correlation between glucose and nonmitochondrial respiration (Fig. 2) suggests that those who are insulin-resistant use an alternative and less efficient means of energy production. The body responds to the imbalance of nutrient intake and expenditure by storing these biomacromolecules as fat for later use such as gluconeogenesis.

Although the groups were similar demographically, there were differences observed in weight, BMI z-score, and waist-to-hip ratio, coupled with biochemical index differences in fasting glucose and insulin, HOMA-IR, cholesterol, and triglycerides. These variables are collinear with IR, and it is possible that difference in mitochondrial respiration relates to these other variables, but the sample size in our study was too small to be able to differentiate. Between the two groups, there were no observed differences in the use of, ever use, and exposure to cART, suggesting that treatment is unlikely to have a substantial influence on our findings. However, protease inhibitors, which more than 60% of the patients in both groups were receiving, have been linked to IR [21,22].

Due to the design of this study, long-term changes in mitochondrial respiration could not be evaluated. We elected to focus evaluations on those who were HIV-infected and who had prior use of ART, differentiated only by the characteristic of whether they were insulin-resistant or not. Future studies are warranted to evaluate mitochondrial respiration in healthy patients and HIV-exposed but uninfected patients for comparison. The increase in unchecked oxidative stress is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and IR, which is further characterized by abnormal energy metabolism as evidenced by alterations in mitochondrial DNA damage and cellular respiration. Cellular respiration involves both nuclear-encoded and mitochondrial-encoded genes. Future studies should examine critical genes involved with mitochondrial biogenesis and function.

IR and its attendant T2DM carry significant morbidity and mortality in the HIV population. Identifying potential causes is a critical step toward alleviating this burden of disease. The strength of this study lies in the evaluation and utility of PBMCs as a surrogate for insulin-sensitive tissues, the procurement of which is difficult or prohibitive, especially in children. Similar mitochondrial studies are being done with monocytes from patients procured postoperatively after cardiac surgery [23]. Collectively, findings from this study set the foundation to further characterize mitochondrial molecular underpinnings as mechanisms of metabolic disease with minimal invasiveness. Using data from this preliminary study, formative hypotheses for future cross-sectional and longitudinal investigations on mitochondrial biogenesis and function are possible.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: J.K.T. (Project and manuscript development, mitochondrial cellular respiration and Mito Stress Tests), T.L.M. (Clinical Mentor, manuscript development), J.W. (data analysis), D.L.J. (data analysis, manuscript development), M.E.G. (manuscript development), R.B.V.D. (manuscript development), and M.G. (Primary Mentor, project and manuscript development).

We thank the children and families for their participation in PHACS, and the individuals and institutions involved in the conduct of PHACS. The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development with cofunding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Office of AIDS Research, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, through cooperative agreements with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (HD052102) (Principal Investigator: George Seage; Project Director: Julie Alperen) and the Tulane University School of Medicine (HD052104) (Principal Investigator: Russell Van Dyke; Co-Principal Investigators: Kenneth Rich, Ellen Chadwick; Project Director: Patrick Davis). Data management services were provided by Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation (protease inhibitor: Suzanne Siminski), and regulatory services and logistical support were provided by Westat, Inc (protease inhibitor: Julie Davidson).

The following institutions, clinical site investigators and staff participated in conducting PHACS AMP in 2014, in alphabetical order: Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago: Ram Yogev, Margaret Ann Sanders, Kathleen Malee, Scott Hunter; Baylor College of Medicine: William Shearer, Mary Paul, Norma Cooper, Lynnette Harris; Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center: Murli Purswani, Mahboobullah Baig, Anna Cintron; Children's Diagnostic & Treatment Center: Ana Puga, Sandra Navarro, Patricia Garvie, James Blood; Children's Hospital, Boston: Sandra Burchett, Nancy Karthas, Betsy Kammerer; Jacobi Medical Center: Andrew Wiznia, Marlene Burey, Molly Nozyce; Rutgers New Jersey Medical School: Arry Dieudonne, Linda Bettica, Susan Adubato; St. Christopher's Hospital for Children: Janet Chen, Maria Garcia Bulkley, Latreaca Ivey, Mitzie Grant; St. Jude Children's Research Hospital: Katherine Knapp, Kim Allison, Megan Wilkins; San Juan Hospital/Department of Pediatrics: Midnela Acevedo-Flores, Heida Rios, Vivian Olivera; Tulane University Health Sciences Center: Margarita Silio, Medea Jones, Patricia Sirois; University of California, San Diego: Stephen Spector, Kim Norris, Sharon Nichols; University of Colorado Denver Health Sciences Center: Elizabeth McFarland, Alisa Katai, Jennifer Dunn, Suzanne Paul; University of Miami: Gwendolyn Scott, Patricia Bryan, Elizabeth Willen.

Funding: This study was supported by funding to T.L.M. and M.G. (R01 NR012885) and J.K.T. pilot project funding (G12 MD007601) from the National Institutes of Health. The Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS) was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development with cofunding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Office of AIDS Research, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, through cooperative agreements with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (HD052102) and the Tulane University School of Medicine (HD052104).

Note: The conclusions and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institutes of Health or U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflicts of interest

Disclaimers: M.E.G. is a clinical trial consultant for Daiichi Sankyo; a DSMB member for Tolmar; a site investigator for contracted trials with Eli Lilly & Company, Novo Nordisk, and Versartis; an advisory board member for Ipsen, Pfizer, and Sandoz; and a recipient of royalties from McGraw Hill and UpToDate.

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hadigan C, Kattakuzhy S. Diabetes mellitus type 2 and abnormal glucose metabolism in the setting of human immunodeficiency virus. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2014; 43:685–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geffner ME, Patel K, Miller TL, Hazra R, Silio M, Van Dyke RB, et al. Factors associated with insulin resistance among children and adolescents perinatally infected with HIV-1 in the pediatric HIV/AIDS cohort study. Horm Res Paediatr 2011; 76:386–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortuny C, Deya-Martinez A, Chiappini E, Galli L, de Martino M, Noguera-Julian A. Metabolic and renal adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015; 34:S36–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen KF, Dufour S, Shulman GI. Decreased insulin-stimulated ATP synthesis and phosphate transport in muscle of insulin-resistant offspring of type 2 diabetic parents. PLoS Med 2005; 2:e233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaster M. Insulin resistance and the mitochondrial link. Lessons from cultured human myotubes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007; 1772:755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shikuma CM, Day LJ, Gerschenson M. Insulin resistance in the HIV-infected population: the potential role of mitochondrial dysfunction. Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord 2005; 5:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barlow-Mosha L, Eckard AR, McComsey GA, Musoke PM. Metabolic complications and treatment of perinatally HIV-infected children and adolescents. J Int AIDS Soc 2013; 16:18600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dagan T, Sable C, Bray J, Gerschenson M. Mitochondrial dysfunction and antiretroviral nucleoside analog toxicities: what is the evidence?. Mitochondrion 2002; 1:397–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerschenson M, Brinkman K. Mitochondrial dysfunction in AIDS and its treatment. Mitochondrion 2004; 4:763–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma TS, Jacobson DL, Anderson L, Gerschenson M, Van Dyke RB, McFarland EJ, et al. Short communication: the relationship between mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance in HIV-infected children receiving antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013; 29:1211–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.[No authors listed] 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep 1992; 41:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III Body measurements (anthropometry). 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data 2000; 314:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Material Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Network (IMPAACT), International Material Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Network (IMPAACT) Section 2 1007HS laboratory processing. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill BG, Benavides GA, Lancaster JR, Jr, Ballinger S, Dell’Italia L, Jianhua Z, Darley-Usmar VM. Integration of cellular bioenergetics with mitochondrial quality control and autophagy. Biol Chem 2012; 393:1485–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chacko BK, Kramer PA, Ravi S, Johnson MS, Hardy RW, Ballinger SW, et al. Methods for defining distinct bioenergetic profiles in platelets, lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils, and the oxidative burst from human blood. Lab Invest 2013; 93:690–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keane KN, Calton EK, Cruzat VF, Soares MJ, Newsholme P. The impact of cryopreservation on human peripheral blood leucocyte bioenergetics. Clin Sci (Lond) 2015; 128:723–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill BG, Benavides GA, Lancaster JR, Jr, Ballinger S, Dell’Italia L, Jianhua Z, et al. Integration of cellular bioenergetics with mitochondrial quality control and autophagy. Biol Chem 2012; 393:1485–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atabek ME, Keskin M, Yazici C, Kendirci M, Hatipoglu N, Koklu E, et al. Protein oxidation in obesity and insulin resistance. Eur J Pediatri 2006; 165:753–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartman ML, Shirihai OS, Holbrook M, Xu G, Kocherla M, Shah A, et al. Relation of mitochondrial oxygen consumption in peripheral blood mononuclear cells to vascular function in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Vasc Med 2014; 19:67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blazquez D, Ramos-Amador JT, Sainz T, Mellado MJ, Garcia-Ascaso M, De Jose MI, et al. Lipid and glucose alterations in perinatally-acquired HIV-infected adolescents and young adults. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.dos Reis LC, de Carvalho Rondo PH, de Sousa Marques HH, de Andrade SB. Dyslipidaemia and insulin resistance in vertically HIV-infected children and adolescents. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2011; 105:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramer PA, Chacko BK, George DJ, Zhi D, Wei CC, Dell’Italia LJ, et al. Decreased bioenergetic health index in monocytes isolated from the pericardial fluid and blood of postoperative cardiac surgery patients. Biosci Rep 2015; 35:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]