Abstract

The orchid genus Oberonia Lindl., is a taxonomically complex genus characterized by recent species radiations and many closely related species. All Oberonia species are under conservation as listed in the CITES and the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria. Given its difficulties in taxonomy and conservation status, Oberonia is an excellent model for developing DNA barcodes. Three analytical methods and five DNA barcoding regions (rbcL, matK, trnH-psbA, ITS, and ITS2) were evaluated on 127 individuals representing 40 species and 1 variety of Oberonia from China. All the three plastid candidates tested (rbcL, matK, and trnH-psbA) have a lower discriminatory power than the nuclear regions (ITS and ITS2), and ITS had the highest resolution rate (82.14%). Two to four combinations of these gene sets were not better than the ITS alone, but when considering modes of inheritance, rbcL+ITS and matK+ITS were the best barcodes for identifying Oberonia species. Furthermore, the present barcoding system has many new insights in the current Oberonia taxonomy, such as correcting species identification, resolving taxonomic uncertainties, and the underlying presence of new or cryptic species in a genus with a complex speciation history.

Keywords: DNA barcoding, Oberonia, taxonomy, radiation, species identification, ITS

Introduction

Oberonia Lindl. is a monophyletic genus (Tang G. D. et al., 2015) with its infrageneric classification still unclear with involving many closely related and recently radiated species. It comprises about 150–200 species centered in tropical Asia and extending to tropical Africa, NE Australia and the Pacific islands. There are 44 species and 2 varieties distributed in China (Su, 2000; Chen et al., 2009; Lin and Lin, 2009; Ormerod, 2010; Xu et al., 2010; Tian et al., 2013), including some taxonomically complex groups lacking clear species delimitations, such as O. acaulis Griff., O. acaulis var. luchunensis S. C. Chen and O. gongshanensis Ormerod; O. arisanensis Hayata, O. delicata Z. H. Tsi and S. C. Chen, O. japonica (Maxim.) Makino and O. menghaiensis S. C. Chen; O. austro-yunnanensis S. C. Chen and Z. H. Tsi and O. jenkinsiana Griff. ex Lindl.; O. insularis Hayata and O. sinica (S. C. Chen and K. Y. Lang) Ormerod, etc. All of these taxonomically complex groups show slightly differences in the morphology of their leaves or flowers, while in some cases, characters are overlaps between species. For example, O. japonica and O. delicata are morphologically similar in most aspects except for some differences in flower character. The former is characterized by sepals broader than petals (sepals 0.9 mm, petals 0.7 mm), while the latter has equal sepals and petals in width. However, flowers with sepals broader than petals (sepals 0.8 mm, petals 0.6 mm) were also found in the population of O. delicata from type location in Yunnan Province (LYL037). The overlapping characters among species make the discrimination and delineation of this genus more challenging. In addition, Oberonia species are vegetative consensus and have diminutive flowers that are not easily discernable by the naked eye, making their identification and taxonomy exceedingly difficult even for professional taxonomists. Thus, a tool such as DNA barcoding, to aid rapid and accurate identification of these species is critically needed.

Oberonia species in China are mostly distributed in Yunnan, Guangxi, Guangdong, and Hainan provinces which belong to the Indo-Burma hot spots. All of them are endangered and listed in CITES (Conventions on International Trade of Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora, http://www.cites.org/eng/disc/species.shtml) and the IUCN Red List categories and criteria (http://www.zhb.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/bgg/201309/t20130912_260061.htm.) Habitat loss and illegal collection in this region poses a great threat to species survival, particularly in the case of narrow endemic Oberonia species that confined to one location in Yunnan Province (Cardinale et al., 2012). Rapidly and correctly identifying Oberonia species in China could promote the monitoring of endangered taxa.

DNA barcoding is a relatively new tool for species identification (Hebert et al., 2003, 2004) and has been applied in many areas, such as taxonomy (Meier et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2013; Mutanen et al., 2015), the discovery of new or cryptic species (e.g., Burns et al., 2008; Karanovic, 2015; Saitoh et al., 2015), biodiversity assessment and conservation (e.g., Taberlet et al., 2012; Ji et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014), and monitoring the illegal wildlife trades (e.g., Baker, 2008; Gathier et al., 2013). After more than 10 years development, many plastid regions and nuclear regions have been suggested as universal barcodes for land plants, such as rbcL+matK, trnH-psbA, ITS, ITS2, etc. (CBOL Plant Working Group, 2009; Chen et al., 2010; Ren et al., 2010; Li et al., 2011). Although, significant progress has been made in the DNA barcoding, the discrimination of closely related species in recently evolved genera such as Oberonia Lindl., Willows (Salix L.) and Curcuma L. (Twyford, 2014; Chen et al., 2015), still poses a great challenge. Hence, testing DNA barcodes in such taxonomically difficult Oberonia genus could help to further understand the potential of these barcodes. The establishment of an available barcoding system for Oberonia could also facilitate the taxonomy and conservation of these taxa.

Five DNA barcode regions were assessed (rbcL, matK, psbA-trnH, ITS, and ITS2) in 40 species and 1 variety of Oberonia obtained from China. The objectives of this study are to: test the effectiveness of suggested core DNA barcodes (rbcL+matK) in Oberonia; evaluate the resolution of these five barcodes and in 2- to 4-region combinations to correctly identify individuals and discriminate among closely related species; and explore some of the taxonomic implications in Oberonia.

Materials and methods

Taxon sampling, DNA extraction, amplification, sequencing, and sequence downloads

In this study, 127 sequences from 40 species and 1 variety were collected for DNA sequencing, in which 123 sequences representing 39 species and 1 variety were from 6 provinces (Guangdong, Guangxi, Fujian, Hainan, Yunnan, and Tibet) in China. Four sequences from 1 species in Genbank were also included. In order to cover the morphological variability and geographical ranges, more individuals (>7) of widespread species such as O. caulescens Lindl. and O. ensiformis (Sm.) Lindl. were sampled. To test the potential of DNA barcodes, individuals of the taxonomically complex groups (e.g., O. acaulis, O. acaulis var. luchunensis, and O. gongshanensis; O. jenkinsiana and O. austro-yunnanensis; O. arisanensis, O. delicata, O. japonica, and O. menghaiensis; O. insularis and O. sinica) were sampled as much as possible. Detailed information about the samples is included in Table S1. The voucher specimens are deposited in the herbarium of the South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou (IBSC).

Total DNA was isolated from fresh or silica-dried leaves using a modified CTAB method (Doyle and Doyle, 1987). Primers are listed in Table S2. The ITS2 sequence was derived from the ITS (ITS, including ITS1, 5.8 s and ITS2) data directly. Two primer pairs of trnH-psbA were used for amplification and sequencing. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted in a reaction mix (30 μl) each containing 10–20 ng (1–2 μl) of template DNA, 15 μl of 2 × PCR mix (0.005 units/μl Taq DNA polymerase, 4 mM MgCl2, and 0.4 mM dNTPs, TIANGEN), 1 μl of each primer (10 μM) and 11–12 μl of ddH2O. The PCR program started with a 2 min pre-melt stage at 98°C, followed by 36 cycles of 10 s at 98°C, annealing at 51–54°C (51°C for rbcL and ITS, 52°C for matK, 54°C for both two primer pairs of trnH-psbA) for 30 s, followed by 50 s at 68°C, and a final 8 min extension at 68°C. The PCR products were run on 1% agarose gels to check the quality of the amplified DNA. Then, PCR products with high quality were sent to Invitrogen (Shanghai) for purification and sequencing from both directions to reduce sequencing error.

Data analyses

Sequences for each marker were edited and assembled using SEQUENCHER 4.14 (GenCodes, Corp. Ann Arbor) and then manually adjusted using Bioedit v7.1.3.0 (Hall, 1999). To assess the barcoding resolution for all barcodes (rbcL, matK, ITS, ITS2, trnH-psbA, rbcL+matK, rbcL+ITS, rbcL+ITS2, rbcL+trnH-psbA, matK+ITS, matK+ITS2, matK+trnH-psbA, rbcL+matK+ITS, rbcL+matK+ITS2, rbcL+matK+trnH-psbA, rbcL+matK+ITS+trnH-psbA), three analytical methods were employed, i.e., the pair-wise genetic distance method (PWG-distance), the sequence similarity method (TAXONDNA) and a phylogenetic-based method (Neighbor-Joining trees and Bayesian inference trees).

For the pair-wise genetic-based method, six parameters [average inter-specific distance, average theta (Θ) prime and smallest inter-specific distance; average intra-specific distance, average theta (Θ) and largest intra-specific distance] were calculated in Mega7 using the Kimura two-parameter distance model (K2P), to explore the intra- and inter-species variation (Chen et al., 2010; Pang et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2016) We considered discrimination to be successful if the minimum inter-species distance involving a species, represented by more than one individual was larger than its maximum intra-species distance.

The sequence similarity method used the proportion of correct identifications identified with TAXONDNA/ Species Identifier 1.8 program, to assess the potential of all markers for accurate species identification. The “Best Match” (BM) and “Best Close Match” (BCM) tests in TAXONDNA were run for species that were represented by more than one individual (Meier et al., 2006).

For the phylogenetic-based method, Neighbor Joining (NJ) trees of all markers were conducted in Mega7 with K2P model and Bayesian inference (BI) trees were conducted in MrBayes v. 3.1 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, 2001; Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003). If all the individuals of one species were clustered into a monophyletic group with the support nodes above 70% (NJ) or 95% (BI), then the species was considered as successfully identified. Species with a single specimen were included, but lacked depth to calculate significance. Dendrobium strongylanthum Rchb. f. (KF177656, KF143723, KF177553, and GU339107) was the outgroup for the tree-based analysis (Tang G. D. et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015).

Results

PCR amplification, sequencing, and genetic divergence

The characteristics of five DNA barcoding regions and their combinations are shown in Table 1. When evaluated separately, rbcL, matK, and ITS had very high success rates (100%) for PCR amplification and sequencing using a single primer pair. Although, trnH-psbA also exhibited relatively high amplification success of 95.12% with two primer pairs, only 7 samples (5.69%) were successfully amplified and sequenced using the commonly used primer pair trnH2/psbAF (Sang et al., 1997; Tate and Simpson, 2003). The remaining samples were, however, generated for trnH-psbA using another primer trnH(GUG)/psbA (Hamilton, 1999). Overall, the aligned length of the five markers ranged from 269 bp (ITS2) to 1187 bp (rbcL). A total of 486 new sequences were submitted to NCBI, which included 123 sequences of each rbcL, matK, and ITS, separately, and 117 sequences of trnH-psbA, were submitted to NCBI (Table S1). In addition, we downloaded 12 sequences of O. mucronata (D. Don) Ormerod and Seidenf. from NCBI, including 4 sequences each of rbcL, matK, and ITS, respectively (JN005593, JN005592, JN005591, JN005590; JN004531, JN004530, JN004529, JN004528; JN114637, JN114636, JN114635, and JN114634). In total, 127 accessions of rbcL, matK, and ITS representing 40 species and 1 variety and 117 accessions of trnH-psbA representing 39 species were obtained for further analysis.

Table 1.

Evaluation of five DNA markers and combinations of the markers.

| R | M | I | I2 | T | R+M | R+I | M+I | R+M+I | R+M+I2 | R+M+T | R+M+I+T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universality of primers | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Rate of PCR success (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Rate of sequencing success (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95.12 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Aligned length (bp) | 1187 | 815 | 827 | 269 | 1001 | 2002 | 2014 | 1642 | 2829 | 2271 | 3003 | 3830 |

| Average intra-distance (%) | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.45 | 0.57 | 0.82 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.31 |

| Average inter-distance (%) | 0.57 | 1.90 | 6.74 | 9.92 | 2.25 | 1.14 | 3.08 | 4.21 | 2.70 | 2.08 | 1.33 | 2.63 |

| Average theta (Θ) (%) | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.70 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.22 |

| Coalescent Depth (%) | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.91 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.32 |

| Proportion of variable sites (%) | 5.48 | 19.63 | 37.12 | 52.42 | 10.49 | 11.24 | 18.42 | 28.44 | 18.77 | 16.12 | 10.76 | 16.42 |

| Proportion of parsimony sites (%) | 3.96 | 15.34 | 30.35 | 41.26 | 7.29 | 8.34 | 14.50 | 22.90 | 14.56 | 12.07 | 7.69 | 12.30 |

R, rbcL; M, matK; I, ITS; I2, ITS2; T, trnH-psbA.

Among the five markers, ITS2 had the highest proportion of variable sites (52.42%) and parsimony-informative sites (41.26%), and rbcL had the lowest. RbcL showed the lowest intra-specific and inter-specific divergence as well, whilst trnH-psbA showed the highest intra-specific divergence (0.82%), followed by ITS2 (0.57%). However, the greatest inter-specific distance was found in ITS2 (9.92%), followed by ITS (6.74%).

The average intra- and inter-specific divergence in the 11 combinations varied from 0.14 to 0.45% and 1.00 to 4.21%, respectively (Table 1). The combinations of matK+trnH-psbA and matK+ITS showed the highest intra- and inter-specific genetic divergence, respectively. The core barcode rbcL+matK and the combination of rbcL+trnH-psbA had the lowest intra-specific genetic divergence, respectively (Table 1).

DNA barcoding gap assessment

The relative distribution of K2P distances based on single barcodes and their combinations indicated that ITS and ITS2 had relatively clear barcoding gaps, while the remaining three tested candidate barcodes and their combinations had overlaps between their inter- and intraspecific distances (Figure S1).

Species resolution of candidate barcodes

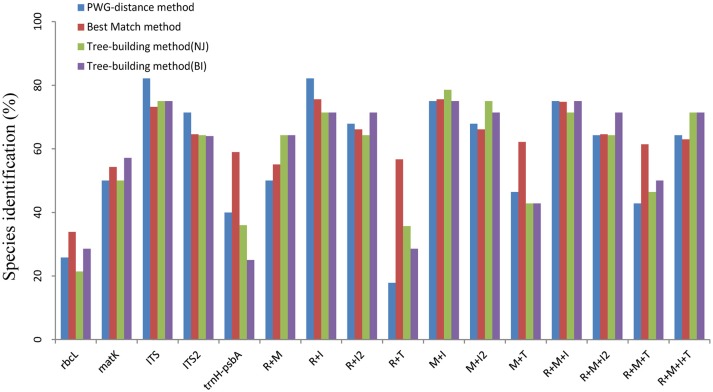

For the PWG-distance method, we used the local barcoding gap to reveal the species resolution power of candidate barcodes. That is, when a minimum inter-specific distance larger than the maximum intra-specific distance of a species, we considered it successfully identified. The proportion of the local barcoding gap varied among the markers tested (Figure S1 and Figure 1). Among single regions, the ITS exhibited the best species resolution (82.14%), followed by ITS2 (71.43%). In contrast, rbcL had the lowest species resolution (25.81%). Of the 11 combinations, rbcL+ITS showed the highest species resolution (82.14%), while rbcL+trnH-psbA showed the lowest species resolution (71.86%).

Figure 1.

Species discrimination rates of multiple candidate barcodes in Oberonia. R, rbcL; M, matK; I, ITS; I2, ITS2; T, trnH-psbA.

The TAXONDNA analysis based on BM and BCM methods exhibited similar discrimination success (Table 2). The ITS had the highest success rate for the correct identification of species (BM and BCM: 73.22%) among the five single barcodes, followed by the ITS2 (BM and BCM: 64.56%), whilst rbcL had the lowest resolution rate (BM and BCM: 33.85%). Among the 11 combinations, rbcL+ITS and matK+ITS performed the best (BM and BCM: 74.59%), followed by rbcL+matK+ITS (BM and BCM: 74.80%). However, the core barcode rbcL+matK demonstrated the lowest species resolution rate (BM and BCM: 55.11%).

Table 2.

Identification success based on the “best match” and “best close match” analysis methods.

| Region | Best match | Best close match | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct (%) | Ambiguous (%) | Incorrect (%) | Correct (%) | Ambiguous (%) | Incorrect (%) | |

| R | 33.85 | 59.84 | 6.29 | 33.85 | 59.05 | 6.29 |

| M | 54.33 | 37.79 | 7.87 | 54.33 | 35.43 | 7.87 |

| I | 73.22 | 16.53 | 10.23 | 73.22 | 16.53 | 4.72 |

| I2 | 64.56 | 26.77 | 8.66 | 64.56 | 26.77 | 4.72 |

| T | 58.97 | 20.51 | 20.51 | 58.97 | 20.51 | 20.51 |

| R+M | 55.11 | 30.7 | 14.17 | 55.11 | 29.92 | 12.59 |

| R+I | 75.59 | 12.59 | 11.81 | 75.59 | 12.59 | 7.87 |

| R+I2 | 66.14 | 23.62 | 10.23 | 66.14 | 22.83 | 7.08 |

| R+T | 56.69 | 21.25 | 22.04 | 56.69 | 21.25 | 22.04 |

| M+I | 75.59 | 12.59 | 11.81 | 75.59 | 12.59 | 7.87 |

| M+I2 | 66.14 | 23.62 | 10.23 | 66.14 | 22.04 | 8.66 |

| M+T | 62.2 | 14.17 | 23.62 | 62.2 | 14.17 | 23.62 |

| R+M+I | 74.8 | 12.59 | 12.59 | 74.8 | 12.59 | 8.66 |

| R+M+I2 | 64.56 | 25.19 | 10.23 | 64.56 | 25.19 | 7.08 |

| R+M+T | 61.41 | 14.17 | 24.4 | 61.41 | 14.17 | 24.4 |

| R+M+I+T | 62.99 | 10.23 | 26.77 | 62.99 | 10.23 | 25.98 |

R, rbcL; M, matK; I, ITS; I2, ITS2; T, trnH-psbA.

The Neighbor Joining (NJ) and Bayesian inference (BI) tree-building method showed similar discriminatory results (Figure 1). Among the five single barcodes, the ITS demonstrated the best discrimination power (NJ tree and BI tree: 75%), followed by ITS2, while rbcL and trnH-psbA had the lowest discrimination power. In the 11 combination barcodes, matK+ITS reached the highest resolution power (NJ tree: 78.57%; BI tree: 75%), followed by rbcL+ITS, rbcL+matK+ITS, and rbcL+matK+ITS+trnH-psbA. The core barcode rbcL+matK recommended by COBL had poor resolution (NJ tree and BI tree: 64.29%), and only slightly better than all combinations with trnH-psbA (rbcL+trnH-psbA, matK+ trnH-psbA, and rbcL+matK+trnH-psbA).

Discussion

Universality of DNA barcodes

Primer universality is an important criterion for an ideal DNA barcode (Kress and Erickson, 2007). In this regard, the rbcL, matK, and ITS had the best performance in PCR amplification and sequencing among the four regions (successfully amplifying and sequencing 100% samples), consistent with many previous studies (Xu et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2015). However, compared to the above three barcodes, trnH-psbA had a relatively low sequencing success rate of 95.12% when two primer pairs were used. This was due largely to poly (T) tracts at about 100 bp in the forward direction when sequencing. In addition, a 230 bp indel in three sequences of two species, i.e., O. intermedia King and Pantl and O. delicata resulted in alignment difficulties. As for the insertion events, small inversions associated with palindromes, and sequencing problems related to mononucleotide repeats within this non-coding chloroplast region will complicate its use as a barcode (Whitlock et al., 2010). Thus, sequence alignment of this region must be careful to avoid overestimates of the substitution events.

The resolution of tested candidate barcodes in Oberonia

When evaluated alone, the three plastid regions studied (rbcL, matK, trnH-psbA) had a resolution ranging from 21.43 to 57.14% (based on tree-building analysis), which is much lower than the discriminatory rate of nuclear region (Figure 1). Thus, all the single plastid regions are not recommended as DNA barcodes for the genus Oberonia. The low resolution of chloroplast regions has been previously reported in other plants including Paphiopedilum (25.74%), Curcuma (21.66%), and Quercus (0%) (Piredda et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2015). This could be due to the lower substitution rates that are found in plastid genomes, relative to their nuclear regions. Consequently, this highlights a need to search for nuclear DNA barcodes.

For the nuclear genome, the ITS and ITS2 generally provided better identification rates than the chloroplast sequences (Chen et al., 2010; Yao et al., 2010; Li et al., 2011). Likewise, the ITS and ITS2 have more parsimony informative sites, larger inter-specific distances and more discriminatory power than chloroplast regions in this study. In comparison the ITS distinguished 75% of monophyletic species, which was the best discrimination performance among the five loci (Figure 1). Meanwhile, any combinations with ITS produced better results than those combinations without (Figure 1 and Table 1). According to some previous results, it is difficult to amplify and directly sequence the region in some taxa because of incomplete concerted evolution of this multiple-copy region caused by hybridization or other factors (Alvarez and Wendel, 2003). However, it is not a problem in Oberonia and it has been widely used to generate phylogenies in many orchid taxa (Koehler et al., 2002; Zhai et al., 2014; Tang Y. et al., 2015). The amplification and sequencing rates of the ITS in this study were nearly 100%. Overall, for a single barcode, the ITS is the best candidate for Oberonia. Meanwhile, our results indicate that the ITS2 alone or in combinations with plastid markers did not have a higher discriminatory power than the ITS and/or its corresponding combinations (Figure 1 and Table 1). However, considering the ease of amplification, we suggest that the ITS2 may be an ideal supplementary barcode when ITS amplification has failed.

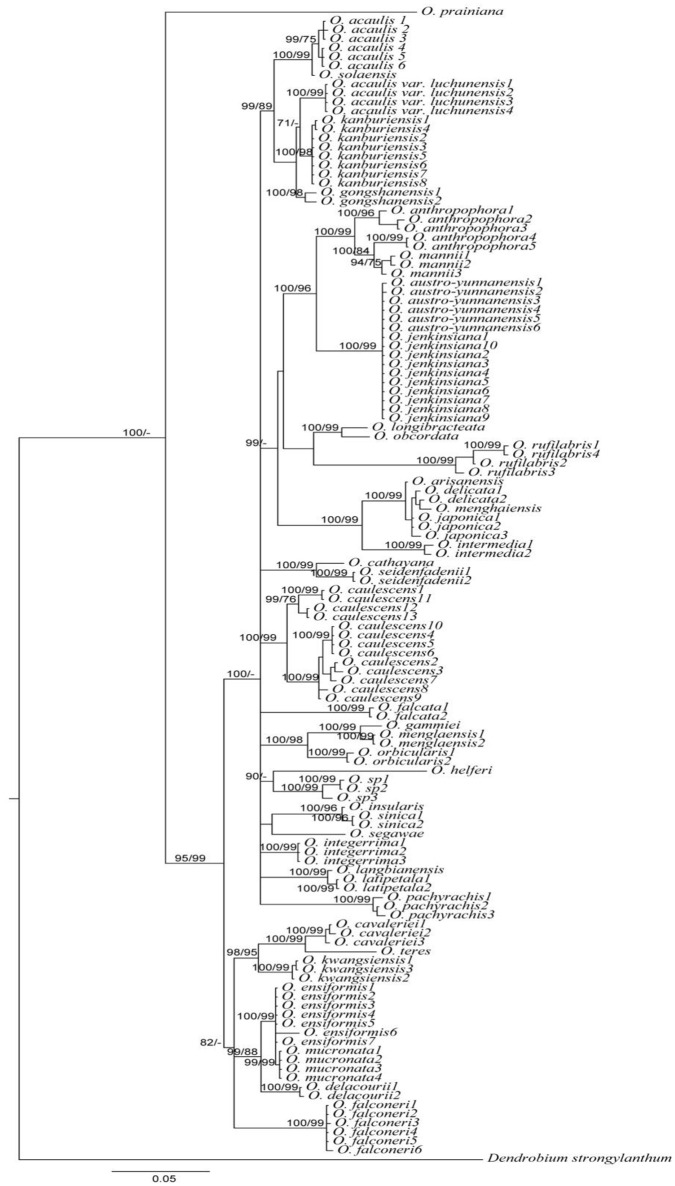

Multi-locus barcodes have been suggested as DNA barcodes for land plants and can often improve the resolution rate of species identification (CBOL Plant Working Group, 2009; Li et al., 2011). In this study, the two-locus barcode rbcL+matK, recommended by the CBOL Plant Working Group (2009), had a low discrimination rate of 64.29% based on the Tree-building method (Figure 1), which was lower than the identification rate of 72% proposed by the CBOL Plant Working Group (2009). One of the most plausible explanations for this discrepancy is that the CBOL Plant Working Group focused on assessing the relative, rather than the absolute discriminatory power of the tested barcodes. We sampled more closely related species within the Oberonia genus and while rbcL and matK discriminates among genera well, the resolution rates of these two markers, alone and in combination, decreased at infrageneric levels, especially within recently evolved genera. Of the 2- to 4- combinations of the five loci tested, rbcL+ITS and matK+ITS exhibited the best discriminatory performance, almost the same as the single ITS barcode (Figure 2, Figures S2, S3). In plant DNA barcoding studies, the use of markers from different genomes with different modes of inheritance has been suggested, because such combinations of DNA markers will further our understanding of species delimitation and the evolutionary processes of speciation (Li et al., 2011). Although the resolution rates of rbcL+ITS and matK+ITS were not better than the single marker ITS itself, we suggest that the combination marker either rbcL+ITS or matK+ITS, should be the first choice to barcode Oberonia species.

Figure 2.

Bayesian inference (BI) tree based on the combination of matK+ITS sequences in Oberonia. Numbers on branches represent BI and NJ support values, respectively.

Implications of DNA barcoding for the current taxonomy of Oberonia

The results obtained in this study shed some light on the identification and taxonomy of the genus Oberonia. In previous DNA barcoding studies on a single genus or between closely related groups, species misidentification can be corrected with DNA barcoding (Pryer et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012; Yan et al., 2015). In the present study, the sample O. kanburiensis 1 was initially identified as O. acaulis Griff., based on leaf morphology (lacked flowers). DNA barcoding showed that the sequences of this sample were different from the other samples of this species, and it continually clustered with O. kanburiensis Seidenf. sequences. Confusion often occurs between O. acaulis and O. kanburiensis, because their morphology is similar prior to flowering. After blooming we rechecked the specimen and confirmed that this accession was misidentified and was in-fact O. kanburiensis. Such misidentifications were also found in O. delacourii 1 and O. delacourii 2 which were initially identified as O. ensiformis (Smith) Lindl. based on leaf morphology (lacked flowers). This finding indicates that DNA barcoding can differentiate species, with small sample input, great speed, and higher reliability, than previous methods. Thus, a more robust method has been demonstrated for endangered species monitoring in Oberonia genus.

In addition to the effectiveness of correcting misidentified specimen, DNA barcoding could also help in resolving taxonomic uncertainties. For example, O. austro-yunnanensis S. C. Chen et Z. H. Tsi and O. jenkinsiana Griff. ex Lindl. were considered as two separate species, discriminated by a joint at the base of the leaf (O. austro-yunnanensis with a basal joint vs. O. jenkinsiana without a basal joint) and subtle differences in the lip of flowers. After carefully checking the specimen and the original literature, we found that neither O. austro-yunnanensis nor O. jenkinsiana have joints at the base of the leaf, and are morphologically similar in most respects. We suspect that these are the same species. In the phylogenetic tree (Figure 2) O. austro-yunnanensis continually clustered with O. jenkinsiana. Besides, O. jenkinsiana is a widespread species and the geographical distribution ranges of these two species overlap. Therefore, our analysis implies that species with identical morphology, distribution, and sequences should be treated as one species. It is also probable that O. sinica and O. insularis reflect a similar situation. In another situation, Oberonia acaulis var. luchunensis are treated as a variety of O. acaulis, but in the light of these DNA barcoding results and the large difference in morphology, O. acaulis var. luchunensis could be raised to an independent species rather than a variety of O. acaulis, although further work is necessary (Figure 2).

Discovery of new or cryptic species is an important application of DNA barcoding within taxonomy (DeSalle et al., 2005). Many studies have employed the DNA barcoding to discover new or cryptic species in a broad range of animals and plants (Burns et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2011; Saitoh et al., 2015). In our study, some taxa such as samples Oberonia sp. 1, 2, 3 are similar to Oberonia caulescens Lindl. with subtle morphological differences in flowers and leaves, not withholding geographical divergences. However, they did not cluster with O. caulescens in the phylogenetic trees, indicating the existence of a new or cryptic species, yet additional study is necessary.

Morphological characterization associated with geographical, ecological, reproductive, and molecular data will facilitate the construction of a robust taxonomic system for any particular taxa. However, taxonomy and species delimitation within a single genus, especially genera with closely related species, is more difficult. In our study, despite the excellent performance of DNA barcoding in the Oberonia species from China, DNA barcoding does have difficulties in discriminating closely related species. For example, taxonomic complex group O. arisanensis, O. delicata, O. japonica, and O. menghaiensis are morphological similar with subtle differences in the diagnostic characteristic of their flowers. DNA barcoding did not discriminate these four species and they all clustered together in the rbcL+ITS tree and matK+ITS tree (Figure 2, Figures S2, S3). Another case for DNA barcoding failure occurred in O. anthropophora, which displayed incongruent signals of nuclear and plastid gene regions (Figures S2, S3). The slow rate of molecular evolution, paralogy, incidence of hybridization, introgression, and incomplete sorting of ancestral polymorphisms are the most likely sources of DNA barcoding failure for closely related Oberonia species (Funk and Omland, 2003; Hollingsworth et al., 2011; León-Romero et al., 2012). The exploration of more molecular markers, such as SNP and SSR, are needed to develop DNA barcodes to assist in species identification (Liu et al., 2008; Yuan et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2012). This data will promote progress in DNA barcoding, while also facilitate the identification of endangered species.

Author contributions

Designed the study: YL, YT, and FX. Performed the experiment and analyzed the data: YL and YT. Wrote the paper: YL, YT, and FX. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 31370231).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Hong-Feng Chen, Prof. Qi-Fei Yi, Dr. Huai-Zhen Tian, Prof. Yan-Liu, De-Ping Ye, Jian-Wu Li, Qiang Liu, Ming-Zhong Huang, and Ya-Ping Chen for their assistance in the sample collection. We also thank Dr. Hai-Fei Yan and Yu Zhang (South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for their help in experiments, data analysis and revising the manuscripts. We thank Dr. Lei Duan and Dr. Juan Chen for revising the manuscripts.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.01791/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alvarez I., Wendel J. F. (2003). Ribosomal ITS sequences and plant phylogenetic inference. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 29, 417–434. 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00208-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker C. S. (2008). A truer measure of the market: the molecular ecology of fisheries and wildlife trade. Mol. Ecol. 17, 3985–3998. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03867.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J. M., Janzen D. H., Hajibabaei M., Hallwachs W., Hebert P. D. N. (2008). DNA barcodes and cryptic species of skipper butterflies in the genus Perichares in Area de Conservación Guanacaste, Costa Rica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 6350–6355. 10.1073/pnas.0712181105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale B. J., Duffy J. E., Gonzalez A., Hooper D. U., Perrings C., Venail P., et al. (2012). Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 486, 59–67. 10.1038/nature.11148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CBOL Plant Working Group (2009). A DNA barcode for land plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12794–12797. 10.1073/pnas.0905845106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Zhao J. T., Erickson D. L., Xia N., Kress W. J. (2015). Testing DNA barcodes in closely related species of Curcuma (Zingiberaceae) from Myanmar and China. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 15, 337–348. 10.1111/1755-0998.12319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. C., Ormerod P., Wood J. J. (2009). Oberonia Lindl., in Flora of China, Vol. 25, eds Wu Z. Y., Raven P. H., Hong D. Y.(Beijing; St. Louis, MO: Science Press and Missouri Botanical Garden Press; ), 236–245. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Yao H., Han J., Liu C., Song J., Shi L., et al. (2010). Validation of the ITS2 region as a novel DNA barcode for identifying medicinal plant species. PLoS ONE 5:e8613. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuénoud P., Savolainen V., Chatrou L. W., Powell M., Grayer R. J., Chase M. W. (2002). Molecular phylogenetics of Caryophyllales based on nuclear 18S rDNA and plastid rbcL, atpB, and matK DNA sequences. Am. J. Bot. 89, 132–144. 10.3732/ajb.89.1.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSalle R., Egan M. G., Siddall M. (2005). The unholy trinity: taxonomy, species delimitation and DNA barcoding. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 360, 1905–1916. 10.1098/rstb.2005.1722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J., Doyle J. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fay M. F., Swensen S. M., Chase M. W. (1997). Taxonomic affinities of Medusagyne oppositifolia (Medusagynaceae). Kew Bull. 52, 111–120. 10.2307/4117844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Funk D. J., Omland K. E. (2003). Species-level paraphyly and polyphyly: frequency, causes, and consequences, with insights from animal mitochondrial DNA. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34, 397–423. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gathier G., van der Niet T., Peelen T., van Vugt R. R., Eurlings M. C., Gravendeel B. (2013). Forensic identification of CITES protected slimming cactus (Hoodia) using DNA barcoding. J. Forensic Sci. 58, 1467–1471. 10.1111/1556-4029.12184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. Y., Huang L. Q., Liu Z. J., Wang X. Q. (2015). Promise and challenge of DNA barcoding in venus slipper (Paphiopedilum). PLoS ONE 11:e0146880. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. A. (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. B. (1999). Four primer pairs for the amplification of chloroplastic intergenic regions with intraspecific variation. Mol. Ecol. 8, 513–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert P. D., Cywinska A., Ball S. L., deWaard J. R. (2003). Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 270, 313–321. 10.1098/rspb.2002.2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert P. D. N., Penton E. H., Burns J. M., Janzen D. H., Hallwachs W. (2004). Ten species in one: DNA barcoding reveals cryptic species in the neotropical skipper butterfly Astraptes fulgerator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 14812–14817. 10.1073/pnas.0406166101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth P. M., Graham S. W., Little D. P. (2011). Choosing and using a plant DNA barcode. PLoS ONE 6:e19254. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Zhang A., Mao S., Huang Y. (2013). DNA Barcoding and species boundary delimitation of selected species of Chinese Acridoidea (Orthoptera: Caelifera). PLoS ONE 8:e82400. 10.1371/journal.pone.0082400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck J. P., Ronquist F. (2001). MRBAYES: bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17, 754–755. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y., Ashton L., Pedley S. M., Edwards D. P., Tang Y., Nakamura A., et al. (2013). Reliable, verifiable and efficient monitoring of biodiversity via metabarcoding. Ecol. Lett. 16, 1245–1257. 10.1111/ele.12162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanovic I. (2015). Barcoding of ancient lake Ostracods (Crustacea) reveals cryptic speciation with extremely low distances. PLoS ONE 10:e0121133. 10.1371/journal.pone.0121133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler S., Williams N. H., Whitten W. M., do Amaral M. C. E. (2002). Phylogeny of the Bifrenaria (Orchidaceae) complex based on morphology and sequence data from nuclear rDNA internal transcribed spacers (ITS) and chloroplast trnL-trnF region. Int. J. Plant Sci. 163, 1055–1066. 10.1086/342035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kress W. J., Erickson D. L. (2007). A two-locus global DNA barcode for land plants, the coding rbcL gene complements the non-coding trnH-psbA spacer region. PLoS ONE 2:e508. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- León-Romero Y., Mejía O., Soto-Galera E. (2012). DNA barcoding reveals taxonomic conflicts in the Herichthys bartoni species group (Pisces: Cichlidae). Mol. Ecol. Resour. 12, 1021–1026. 10.1111/1755-0998.12018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. Z., Gao L. M., Li H. T., Wang H., Ge X. J., Liu J. Q. (2011). Comparative analysis of a large dataset indicates that internal transcribed spacer (ITS) should be incorporated into the core barcode for seed plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 19641–19646. 10.1073/pnas.1104551108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T.-P., Lin W.-M. (2009). Newly discovered native orchids of taiwan (III). Taiwania 54, 323–333. 10.6165/tai.2009.54(4).323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Möller M., Gao L. M., Zhang D. Q., Li D. Z. (2011). DNA barcoding for the discrimination of Eurasian yews (Taxus L., Taxaceae) and the discovery of cryptic species. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 11, 89–100. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02907.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Yan H. F., Newmaster S. G., Pei N., Ragupathy S., Ge X. J. (2014). The use of DNA barcoding as a tool for the conservation biogeography of subtropical forests in China. Divers. Distrib. 21, 188–199. 10.1111/ddi.12276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Meng J., Sun X. (2008). A novel feature-based method for whole genome phylogenetic analysis without alignment: application to HEV genotyping and subtyping. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 368, 223–230. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier R., Shiyang K., Vaidya G., Ng P. K. (2006). DNA barcoding and taxonomy in Diptera: a tale of high intraspecific variability and low identifications success. Syst. Biol. 55, 715–728. 10.1080/10635150600969864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutanen M., Kekkonen M., Prosser S. W., Hebert P. D., Kaila L. (2015). One species in eight: DNA barcodes from type specimens resolve a taxonomic quagmire. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 15, 967–984. 10.1111/1755-0998.12361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormerod P. (2010). Orchidaceous additions to the flora of yunnan. Taiwania 55, 24–27. 10.6165/tai.2010.55(1).24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pang X., Shi L., Song J., Chen X., Chen S. (2013). Use of the potential DNA barcode ITS2 to identify herbal materials. J. Nat. Med. 67, 571–575. 10.1007/s11418-012-0715-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piredda R., Simeone M. C., Attimonelli M., Bellarosa R., Schirone B. (2011). Prospects of barcoding the Italian wild dendroflora: oaks reveal severe limitations to tracking species identity. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 11, 72–83. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02900.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryer K. M., Schuettpelz E., Huiet L., Grusz A. L., Rothfels C. J., Avent T., et al. (2010). DNA barcoding exposes a case of mistaken identity in the fern horticultural trade. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 979–985. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02858.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves G., Chase M. W., Goldblatt P., Rudall P., Fay M. F., Cox A. V., et al. (2001). Molecular systematics of Iridaceae: evidence from four plastid DNA regions. Am. J. Bot. 88, 2074–2087. 10.2307/3558433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren B. Q., Xiang X. G., Chen Z. D. (2010). Species identification of Alnus (Betulaceae) using nrDNA and cpDNA genetic markers. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 594–605. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02815.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P. (2003). MrBayes 3: bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh T., Sugita N., Someya S., Iwami Y., Kobayashi S., Kamigaichi H., et al. (2015). DNA barcoding reveals 24 distinct lineages as cryptic bird species candidates in and around the Japanese Archipelago. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 15, 177–186. 10.1111/1755-0998.12282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang T., Crawford D., Stuessy T. (1997). Chloroplast DNA phylogeny, reticulate evolution and biogeography of Paeonia (Paeoniaceae). Am. J. Bot. 84, 1120–1136. 10.2307/2446155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H. J. (2000). Oberonia Lindl., in Fl. Taiwan, 2nd Edn., Editorial Committee of Flora of Taiwan, Vol. 5 (Taipei: National Taiwan University; ), 981–984. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Skinner D. Z., Liang G. H., Hulbert S. H. (1994). Phylogenetic analysis of Sorghum and related taxa using internal transcribed spacers of nuclear ribosomal DNA. Theor. Appl. Genet. 89, 26–32. 10.1007/BF00226978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taberlet P., Coissac E., Pompanon F., Brochmann C., Willerslev E. (2012). Towards next-generation biodiversity assessment using DNA metabarcoding. Mol. Ecol. 21, 2045–2050. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05470.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G. D., Zhang G. Q., Hong W. J., Liu Z. J., Zhuang X. Y. (2015). Phylogenetic analysis of Malaxideae (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae): two new species based on the combined nrDNA ITS and chloroplast matK sequences. Guihaia 35, 447–463. 10.11931/guihaia.gxzw201506015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Yukawa T., Bateman R. M., Jiang H., Peng H. (2015). Phylogeny and classification of the East Asian Amitostigma alliance (Orchidaceae: Orchideae) based on six DNA markers. BMC Evol. Biol. 15:96. 10.1186/s12862-015-0376-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate J. A., Simpson B. B. (2003). Paraphyly of Tarasa (Malvaceae) and diverse origins of the polyploid species. Syst. Bot. 28, 723–737. 10.1043/02-64.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H. Z., Hu C., Tong Y. (2013). Two newly recorded species of Oberonia (Orchidaceae) from China. J. Trop. Subtrop. Bot. 21, 231–233. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-3395.2013.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Twyford A. D. (2014). Testing evolutionary hypotheses for DNA barcoding failure in willows. Mol. Ecol. 23, 4674–4676. 10.1111/mec.12892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock B. A., Hale A. M., Groff P. A. (2010). Intraspecific inversions pose a challenge for the trnH-psbA plant DNA barcode. PLoS ONE 5:e11533. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Li D., Li J. W., Xiang X., Jin W., Huang W., et al. (2015). Evaluation of the DNA barcodes in Dendrobium (Orchidaceae) from mainland Asia. PLoS ONE 10:e0115168. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z. H., Jiang H., Ye D. P., Liu E. D. (2010). The Wild Orchids in Yunnan. Kunming: Yunnan Publishing Group Corporation, Yunnan Science & Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yan L. J., Liu J., Möller M., Zhang L., Zhang X. M., Li D. Z., et al. (2015). DNA barcoding of Rhododendron (Ericaceae), the largest Chinese plant genus in biodiversity hotspots of the Himalaya–Hengduan Mountains. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 15, 932–944. 10.1111/1755-0998.12353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H., Song J., Liu C., Luo K., Han J., Li Y., et al. (2010). Use of ITS2 region as the universal DNA barcode for plants and animals. PloS ONE 5:e13102. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z., Chu G., Dan Y., Li J., Zhang L., Gao X., et al. (2012). BRCA1: a new candidate gene for bovine mastitis and its association analysis between single nucleotide polymorphisms and milk somatic cell score. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 6625–6631. 10.1007/s11033-012-1467-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Yuan Z., Tong X., Li Q., Gao W., Qin M., et al. (2012). Phylogenetic study of Oryzoideae species and related taxa of the Poaceae based on atpB-rbcL and ndhF DNA sequences. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 5737–5744. 10.1007/s11033-011-1383-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai J. W., Zhang G. Q., Li L., Wang M., Chen L. J., Chung S. W., et al. (2014). A new phylogenetic analysis sheds new light on the relationships in the Calanthe alliance (Orchidaceae) in China. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 77, 216–222. 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. Y., Wang F. Y., Yan H. F., Hao G., Hu C. M., Ge X. J. (2012). Testing DNA barcoding in closely related groups of Lysimachia L. (Myrsinaceae). Mol. Ecol. Resour. 12, 98–108. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03076.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.