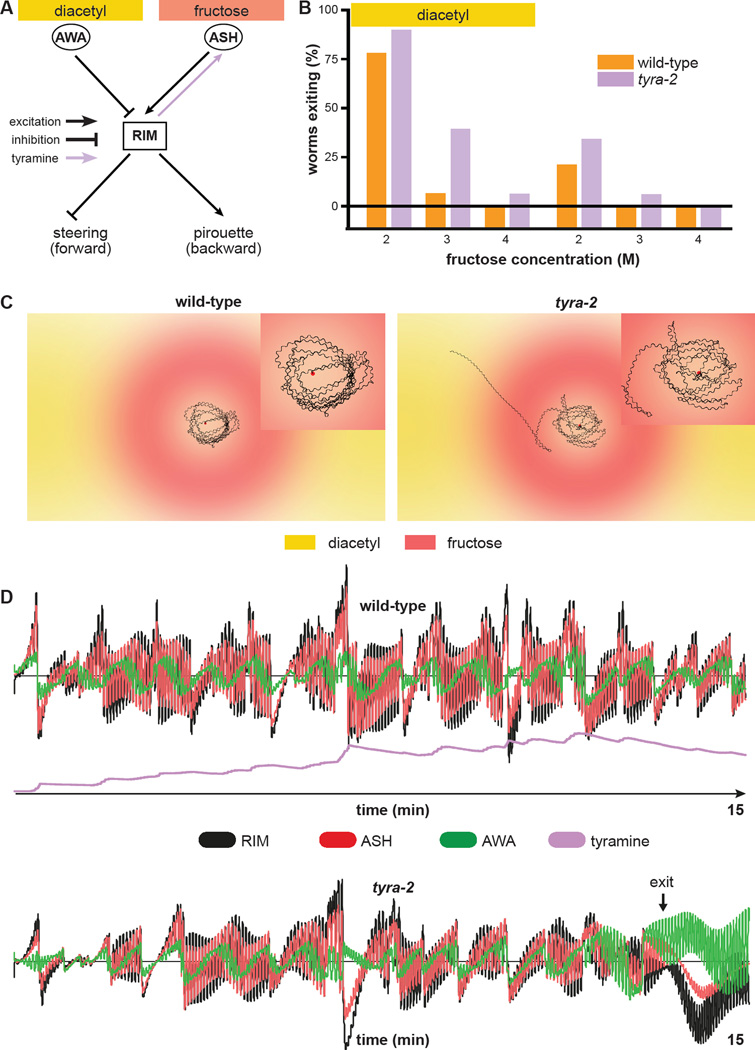

Figure 5. Computational modeling predicts non-linear slow tyramine signaling by RIM to ASH.

(A) Schematic of the simplified nervous system used for computational modeling. AWA and ASH provide direct inhibitory and excitatory inputs onto RIM, respectively. RIM integrates these sensory inputs and directionally biases forward locomotion via inhibition of steering and pirouette modulation. Tyraminergic positive feedback from RIM to ASH increases ASH sensitivity to osmotic stimuli. Simulated tyra-2 null-mutant worms lack the tyraminergic RIM-ASH signal.

(B) Decision balance of simulated wild-type and tyra-2 null-mutant worms encountering a 2 M, 3 M, or 4 M fructose ring in the presence or absence of food odor. n=1000 single worm simulations per genotype and condition.

(C) Sample fifteen-minute trajectories of simulated wild-type and tyra-2 null-mutant worms inside a 3 M ring with food odor outside. Trajectories are magnified in the insets.

(D) Neural activity profiles of AWA, ASH, and RIM during the simulated trajectories in (C). Activity of individual neurons and of tyramine signals are expressed in arbitrary units, plotted to the same scale for the simulated wild-type and tyra-2 null-mutant worms.