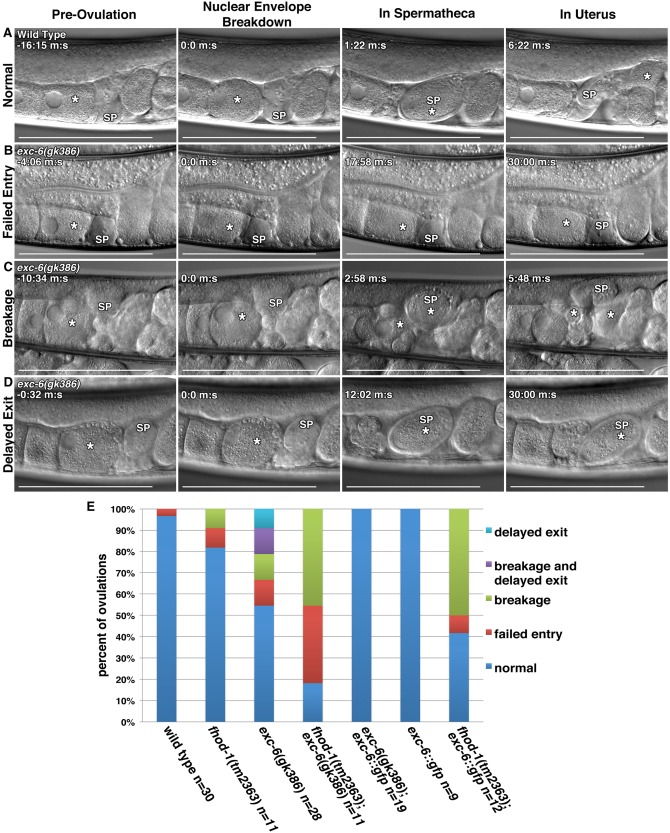

Figure 4.

EXC‐6 and FHOD‐1 promote ovulation. (A‐D) Ovulation was visualized in live worms using DIC microscopy. In all images, (*) indicates the ovulating oocyte or fertilized embryo, and (SP) indicates the spermatheca. (A) Normal ovulation can be subdivided into four landmarks: Pre‐ovulation when the proximal oocyte has an intact nucleus, Nuclear Envelope Breakdown (NEBD) and coincident rounding of the proximal oocyte, In Spermatheca, when ovulation has completed and the oocyte has entered the spermatheca, and In Uterus, when the fertilized embryo (*) has exited the spermatheca to the uterus. In three examples of defective ovulations in exc‐6(gk386) hermaphrodites, we observe: (B) Failed Entry of the proximal oocyte into the spermatheca following NEBD, (C) Breakage of the proximal oocyte into two pieces (two asterisks) during its entry into the spermatheca, and (D) Delayed Exit, in which the fertilized embryo fails to exit the spermatheca within 30 min. Scale bars, 100 µm. Time stamps indicate min:sec. (E) Frequencies of ovulations phenotypes. While ovulations of wild‐type worms were almost always normal, less that 20% of fhod‐1(tm2363);exc‐6(gk386) double‐mutant ovulations were normal. Only 50% of exc‐6(gk386) ovulations were normal. An exc‐6::gfp transgene fully rescued the exc‐6(gk386) defects, had no effect in a wild‐type background, but severely exacerbated ovulation in a fhod‐1(tm2363) background. Shown are the combined results of two independent experiments.