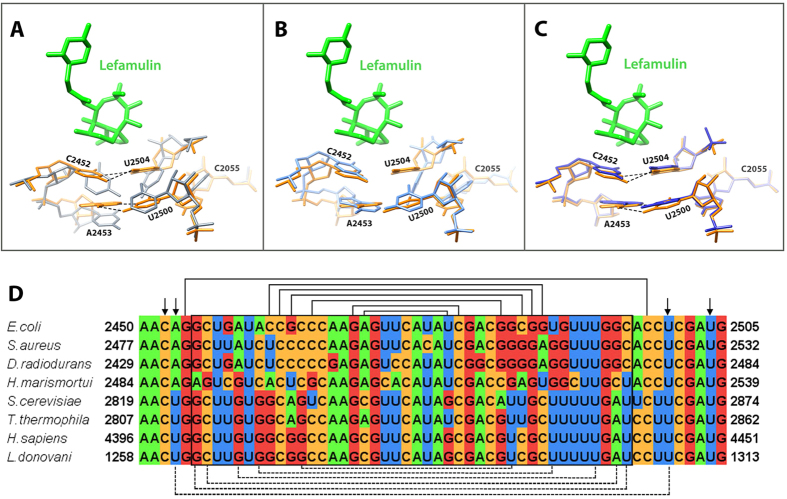

Figure 4. The binding pocket of lefamulin.

(A) SA50S-lef (lefamulin in green and 23S rRNA in orange) superimposed on the structure of human 80S (grey) (4UG0). In S. aureus nucleotides C2452 and U2504 interact with each other (marked with dashed lines) while the same nucleotides in eukaryotes’ structures have the same identity but different orientations, so they cannot interact with each other. Nucleotides A2543 and U2500 are paired (marked with dashed lines) and stacked to C2452 and U2504 in the bacterial ribosomes. In eukaryotes’ structures, nucleotides 2453 and 2500 are both uridines and no interaction between them occurs owing to their orientation. In eukaryotes, U2504 has different orientation than in bacteria which allows pi stacking to A2055 (C in bacteria, A in eukaryotes). This interaction stabilizes the “open” conformation of the PTC which is the key for the pleuromutilins’ selectivity. (B) A superposition of the rRNA H50S-tiamulin structure (light blue) (3G4S) on that of SA50S-lef (orange). In archaea, nucleotides A2543 and U2500 cannot form Watson-Crick base-pair due to the stacking between U2504 and A2055. (C) A superposition of the rRNA apo SA50S structure (blue) (4WCE) on the SA50S-lef (orange) shows that the position of these nucleotides is the same in the bound and the unbound 50S. (D) Multiple sequence alignment of part of the pleuromutilin binding site, comparing the bacterial, archaeal and eukaryotes large ribosomal subunit rRNA. Helix 89 nucleotides, which are part of the PTC, are marked in a box. Arrows are indicating on the nucleotides C2452, A/U2453, U2504 and U2500 which are 1st and 2nd shell from the mutilin moiety. The lines represent Watson-crick base pairs, dashed lines are base pairs only in bacteria.