Abstract

Wet Ag/AgCl electrodes, although very popular in clinical diagnosis, are not appropriate for expanding applications of wearable biopotential recording systems which are used repetitively and for a long time. Here, the development of a low-cost and low-noise active dry electrode is presented. The performance of the new electrodes was assessed for recording electrocardiogram (ECG) and electroencephalogram (EEG) in comparison with that of typical gel-based electrodes in a series of long-term recording experiments. The ECG signal recorded by these electrodes was well comparable with usual Ag/AgCl electrodes with a correlation up to 99.5% and mean power line noise below 6.0 μVRMS. The active electrodes were also used to measure alpha wave and steady state visual evoked potential by recording EEG. The recorded signals were comparable in quality with signals recorded by standard gel electrodes, suggesting that the designed electrodes can be employed in EEG-based rehabilitation systems and brain-computer interface applications. The mean power line noise in EEG signals recorded by the active electrodes (1.3 μVRMS) was statistically lower than when conventional gold cup electrodes were used (2.0 μVRMS) with a significant level of 0.05, and the new electrodes appeared to be more resistant to the electromagnetic interferences. These results suggest that the developed low-cost electrodes can be used to develop wearable monitoring systems for long-term biopotential recording.

Keywords: Brain, electrocardiography, electrodes, electroencephalography, electromagnetic phenomena, evoked potentials

Introduction

Recording of biopotentials is the primary part of many monitoring, diagnosis, and rehabilitation systems. The conventional Ag/AgCl wet electrodes are widely used for biopotential measurements with benefits of simplicity, cheapness, and good technical performance. However, they have also some limitations that prevent their use in expanding applications of wearable wireless systems that are designed to be used during the everyday living. The conductive gel dries over time, and this degrades the signal quality in long-term recordings. Moreover, using the gel makes the electrode placement nontrivial for repeated use of the electrodes and time-consuming when a lot of electrodes have to be used. Moreover, the stained gel on the skin or the hair needs repeatedly washings; otherwise, they may short circuit closely placed electrodes. Finally, allergic reactions are observed in some people when using gel-based electrodes.[1]

Dry electrodes have been designed to receive biopotentials with no need to skin preparation and conductive gel. The main challenge is to fabricate a biocompatible and flexible electrode without gel but with impedance characteristics approaching the wet electrodes. There are various novel designs for measuring electroencephalogram (EEG) or electrocardiogram (ECG) signals including gold coated needle electrodes,[2,3] dry polymer foam electrodes,[4] flexible conductive polymer electrodes,[5] and even textile-based dry electrodes.[6,7] These electrodes can be used passively or as part of an active electrode. The latter is employing an active circuit for preamplification of input signal beside the electrode which significantly improves the sensitivity of the high impedance dry electrode to electromagnetic interferences.[8]

There are two major approaches to design an active circuit for a dry-contact electrode. The first is a simple unity-gain buffer amplifier that only does the impedance conversion for the high impedance electrode. This approach has been widely used in previous studies[5,9,10,11] since it leads to a smaller active electrode. The other one is to amplify and probably filter the signal before sending it to the main recording system.[12,13] In this approach, however, the common mode rejection ratio of the system degrades due to the tolerance of the elements used in the circuitry of the two electrodes which their signals are subtracted. Moreover, a reference signal is necessary in this configuration for each electrode that leads to extra wires.

In this study, two kinds of low cost while low-noise active electrodes were developed based on the first approach. One kind was with a flat surface, and the other was with pins for recording EEG through hair. The performance of these electrodes was assessed based on long time recordings of ECG, EEG alpha wave, and steady-state visual evoked potential (SSVEP). Previous studies that reported the development of dry electrodes either provide no comparison of the signal quality with wet electrodes,[13] or used just general features, for example, the correlation between the recordings to assess the new electrode performance.[2,3,4,5] In this study, however, a comprehensive comparison was performed by including more practical measures including the baseline and power-line noise as well as signal offset and drift in long-term recording.

Methods

Active dry electrodes introduced in this paper employ a simple buffer amplifier as the active circuit and can be used with a predesigned biopotential recording unit with ease and desired compatibility. Several tests were performed to examine the electrode's performance in long-term EEG and ECG recording. Here, the design of the electrodes and the experiments are described.

Electrode construction

Two types of flat and multi-pin dry electrodes were developed and used in this study. The multipin electrode consisted of four silver pins coated with gold each 2.5 mm in diameter aimed to allow EEG recording through the hairs. The flat electrodes were based on brass, coated with gold and were designed for ECG or forehead-EEG recording. The electrodes had a diameter of about 11 mm [Figure 1]. They were installed on a printed circuit board (PCB) which was attached to the main active board.

Figure 1.

Gold coated dry multipin electrode for electroencephalogram recording through the hairs and dry flat electrode for electrocardiogram or forehead-electroencephalogram recording. The electrode's base had a diameter of about 11 mm

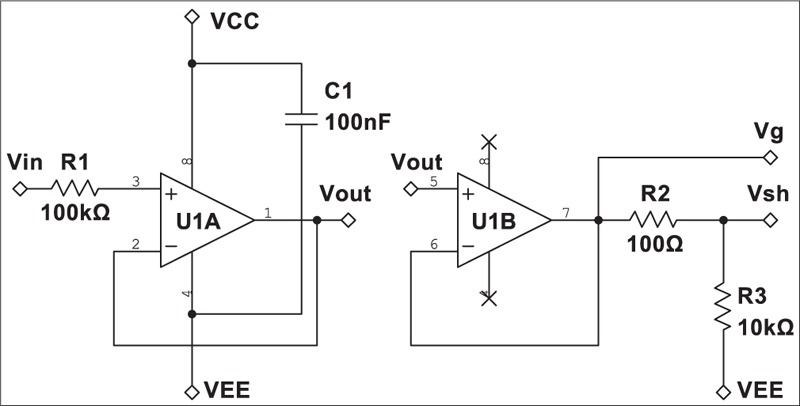

The active circuit

Schematics of the active circuit are shown in Figure 2. The circuit consisted of two buffers. The first buffer picks up the signal from the skin and the second one drives an active shielding/guarding of the circuit as well as the output cable. TI OPA2376 precision op-amp with built-in electrostatic discharge protection was used for the buffers due to its very high input impedance. Its 0.2 pA input bias current, 5 μV input offset voltage, and 0.8 μVPP input voltage noise (at 0.1–10 Hz) have made this device an excellent choice for the job. Since we used a 100 kΩ resistor, the total input noise density of each active electrode can be calculated as below:

Figure 2.

Schematic of the developed active electrode. Vg and Vsh were used for active guarding/shielding of the circuit and output cable, respectively

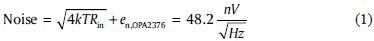

Printed circuit board layout and shielding

Ground planes were used on both sides of the main and the electrode PCBs were used to shield the electrode. The planes were actively driven by the shielding buffer U1B. The well-known guard-ring technique was also employed to reduce the leakage current of the input pins in the first buffer U1A as described in the device datasheet [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Printed circuit board layout of the main active board demonstrating the guard-ring at amplifier's inputs and ground planes for active shielding of the board. The diameter of the board is 22 mm

It is important to protect the circuit against the humidity and dust to preserve good characteristic of the enabled active shielding while providing a hard cover for the sensor that made the packaging procedure much easier and cheaper [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

The final assembled active dry electrodes protected against the humidity and dust by silicon glue

To evaluate the performance of the developed electrodes, simultaneous recordings were performed by these electrodes and conventional wet electrodes. A two-channel wireless battery-powered biopotential recording system was used in these experiments based on TI ADS1294 24-bit analog front-end with a sampling frequency of 250 Hz. Note that no analog high-pass or notch filter was implemented in the recording circuitry.

Electrocardiogram test

Long-term ECG recording (lead I) was performed on 12-year-old healthy male over 4.5 h. During this time, the participant was free to do his usual works while the electrodes were fixed on his hands, however during the recording, he was asked to sit calmly on a chair. Before the experiment, the protocol was clearly described for the participant, and he takes part in the experiment voluntarily. He was informed that he can exit the experiment at any time during the experiment with no hesitation. The ECG signal was recorded periodically during the experiment each time for 3 min. The first recording was performed just after the electrodes were montaged, and the recordings were repeated after each 30 min’ interval which resulted in ten recording. The electrodes were fixed during the whole experiment; therefore, the recordings were samples that could track the pattern of changes in the quality of the recordings affected by the electrode performance.

Electroencephalogram test

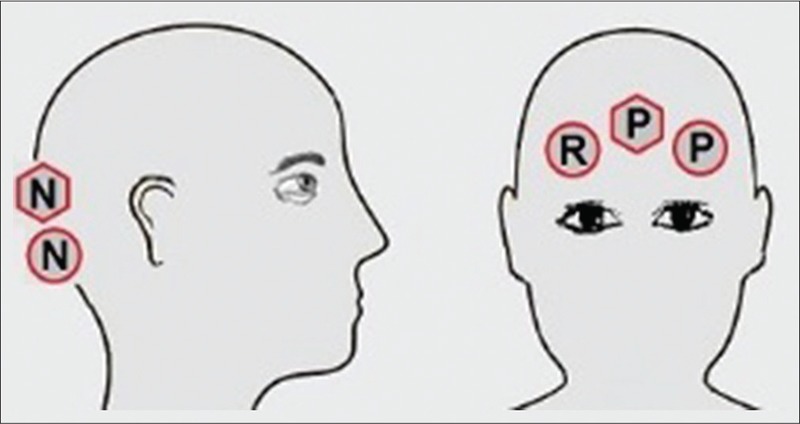

Almost the same procedure was used for long-term EEG recording. The experiment was performed on five healthy male volunteers with the mean age of 20 years over 4.5 h. All the participants were informed about the experiment protocol and participated in the experiment voluntarily. That was also informed that they could leave the experiment at any time during the experiment without any hesitation. The experiment consisted of 10 EEG recordings in each 30 min which consisted of 1-min recording with eyes open, 1 min recording with eyes closed (to detect alpha waves), 0.5 min with eyes open, and finally 0.5 min while looking at a visual stimulus at frequency of 13 Hz (to detect SSVEPs). The conventional gold cup EEG electrodes were used with ten 20 conductive pastes as the wet electrodes. The electrodes were fastened around the participant's head with strap in the way that would be a comfort for him [Figure 5]. The wet electrodes were cleaned from the gel after the experiments performed by each participant.

Figure 5.

Placement of electroencephalogram electrodes around the head. Circles are wet electrodes, hexagons are active electrodes. “P” and “N” represent positive and negative electrodes, respectively, and “R” is the reference electrode

Performance evaluation

The performance of the developed dry electrode was assessed by comparing several performance variables calculated from the recorded signals using the developed dry electrodes and conventional wet electrodes. It will be referred to these variables as the comparison parameters.

Offset was calculated simply by averaging the signal over the whole recording time.

Baseline drift obtained by subtracting the offset of two 1 s intervals, one at the beginning of the signal and the other at 1 min later.

Baseline noise power was also measured, as the power of the signal at the frequencies between 0.3 and 0.7 Hz since possible oscillations in the signal baseline may not reflect in the calculated offset and drift. The chosen frequency band covers the main part of the baseline noise spectrum but just a negligible amount of the primary signal's spectrum.

50-Hz noise amplitude was calculated by first applying a bandpass filter with cutoff frequencies of 45 and 55 Hz and then obtaining the power of the signal at its peak frequency with a bandwidth of 1.6 Hz. Finally, the amplitude of sinusoidal power line interferences was determined using Eq. 2:

Similarity describes how similar two signals are. After filtering DC components of the two intended signals, the Pearson's r-squared (C) was calculated for the filtered signals and their PSDs, to determine time and frequency domain similarities, respectively, according to Eq. 3:

Similarity (%) =100 C2 (3)

Statistical methods

To compare the results of the wet and dry electrodes, GLM statistical test was used. The GLM test is used to assess the difference of two mean values between two independent populations that in each one the members are normal random variables and independent. In our case, the two populations were the calculated parameters of the signals from the conventional and dry electrodes. The hypothesis of the normal distribution and independence of the members in each group were also tested statistically and were significant with P value of 0.05.

Results

Long-term electrocardiogram recording

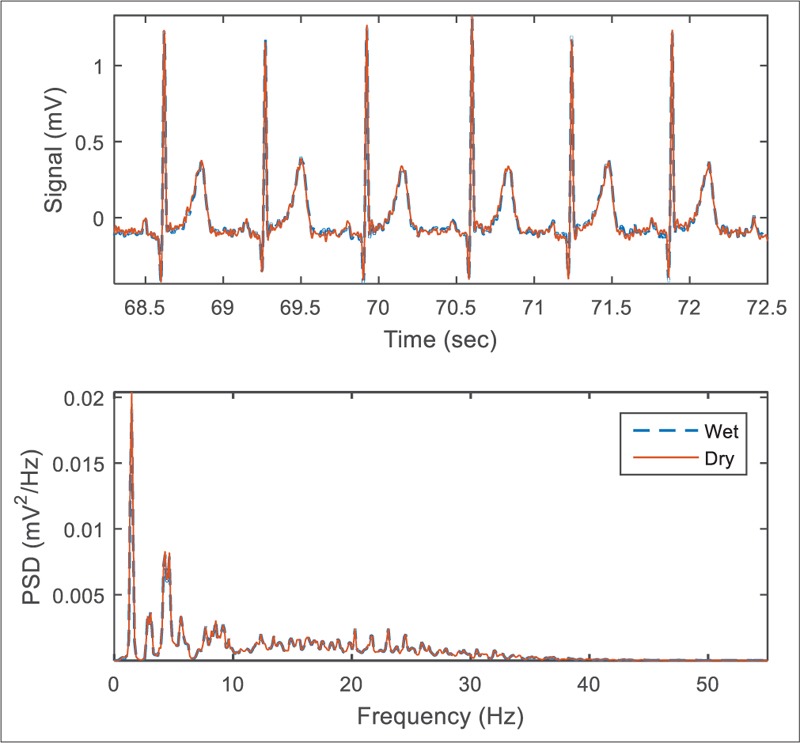

Figure 6 presents sample ECG signals as well as their Welch's PSD recorded by active and wet electrodes. The similarity measure between the signals was 99.34% in time domain and 99.34% in frequency domain. Several distorting parameters measured from these signals were quantitatively calculated which are presented in Table 1. The mean amplitude of 50 Hz noise in the signal recorded by the active electrodes was lower than wet ones in the long-term ECG test because of the properties of active shielding technique. On the other hand, the baseline fluctuation of the ECG signals recorded by the dry electrodes was slightly higher than conventional electrodes, as we expect due to the higher electrode-skin impedance of dry electrodes. However, due to the small number of samples, these differences could not be proved statistically.

Figure 6.

The highly correlated simultaneous electrocardiogram signals related to the first record just after the wet electrodes were installed. A digital 0.5 Hz Butterworth high-pass filter has been applied to remove DC-offset for both signals

Table 1.

Mean of the comparison parameters in ten electrocardiography records (n=10)

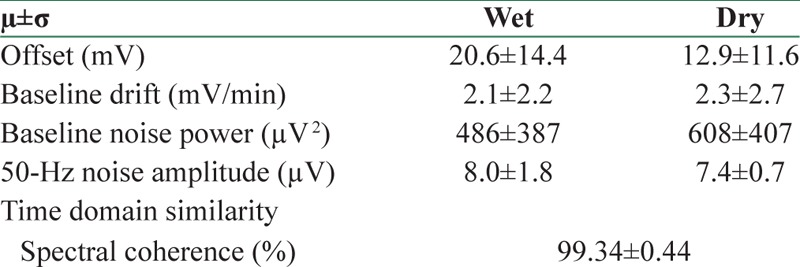

Long-term electroencephalogram recording

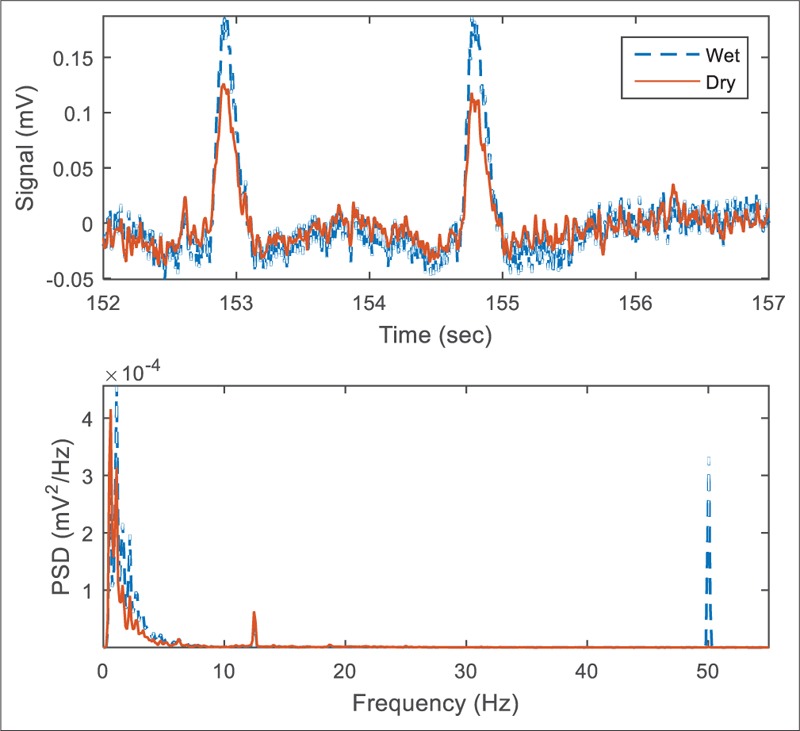

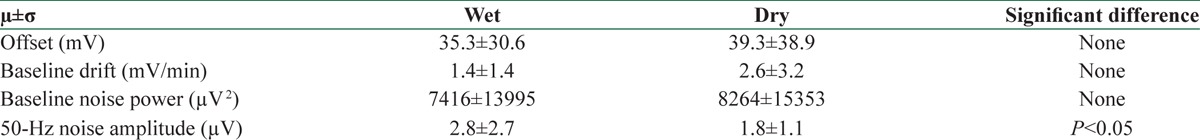

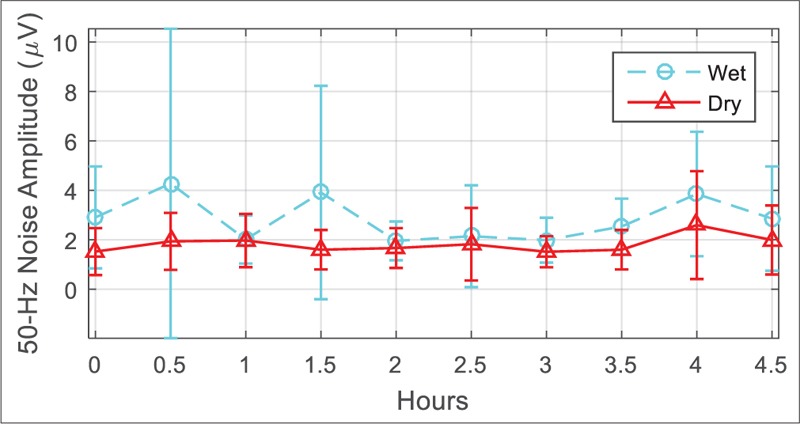

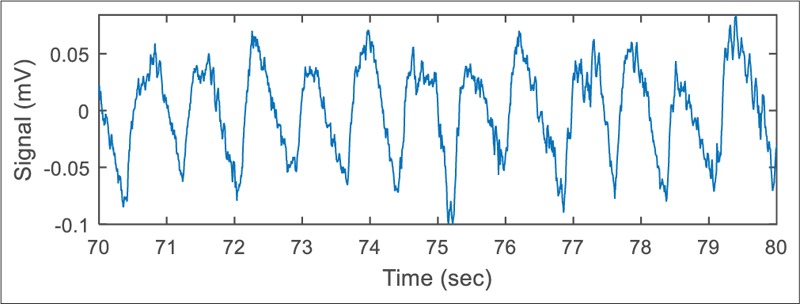

Figure 7 demonstrates sample EEG signals recorded by conventional and dry electrodes. Since the electrodes placed on the head unavoidably were not exactly the same, the EEG signals are not expected to be perfectly matched, and we found a bit variation between the measured evoked potentials power band [Figure 8]. Comparison parameters extracted from the recorded signals are provided in Table 2. The offset, baseline drift, and low-frequency noise power were slightly higher for the dry electrode, whereas the power line noise was lower for dry active electrode [Figure 9]. The difference in 50 Hz noise level was statistically significant (P < 0.05), whereas for other parameters, the differences were not statistically significant.

Figure 7.

Sample electroencephalogram signals recorded when the participant was looking at a 13 Hz visual stimulus. A digital 0.5 Hz Butterworth high-pass filter is applied to remove DC offset. The large 50-Hz peak due to a nearby power line connected noise source is recognizable for the wet electrodes

Figure 8.

Comparison of alpha waves and steady state visual evoked potentials band power between the electrodes in the long-term electroencephalogram test. The bars demonstrate average and standard deviation of values from five participants during the experiment

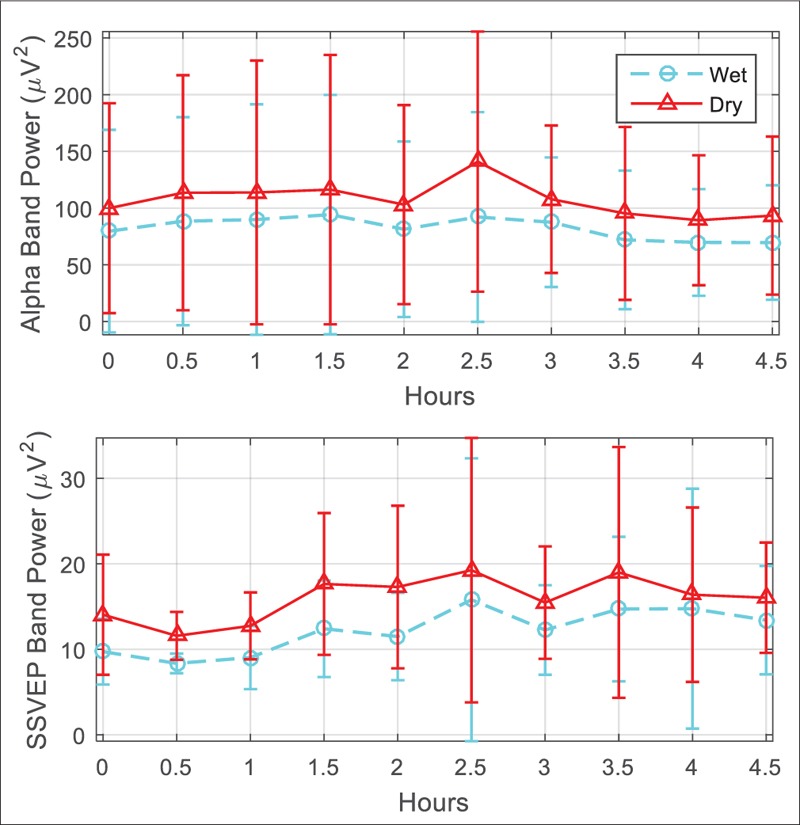

Table 2.

Mean of the comparison parameters in 50 electroencephalography records (n=50)

Figure 9.

Comparison of power line noise level between the electrodes in the long-term electroencephalogram test. The bars demonstrate average and standard deviation of values from five participants during the experiment

Performance of the developed active electrodes was well comparable with the conventional electrodes in recording alpha waves and SSVEPs [Figure 8]. The desired frequency peaks were clearly observable in the power spectrum of the signal.

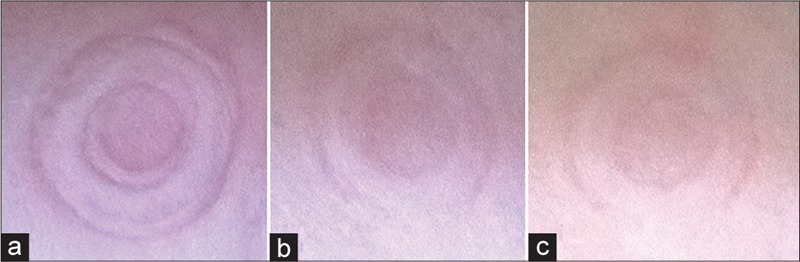

Electrode mark

Since the dry electrodes are used without any paste, a wristband/headband was used in this study to fix them on the skin. This ensured appropriate and stable contact between the dry electrodes and the skin and reduced low-frequency distortion. However, it is important to evaluate the long-term effect of the electrode on the skin. Figure 10 shows electrode marks on the participant's wrist after 4.5 h of ECG recording. The mark on the skin was almost disappeared after about 30 min. For the EEG electrodes, no noticeable marks on the head were observed. For both EEG and ECG recordings, the participants were evaluated the electrodes as not annoying during the whole experiments.

Figure 10.

The mark of dry electrodes on the skin after 4.5 h of electrocardiogram test. (a) Right after the last record, (b) 15 min later and (c) 30 min later

Discussion and Conclusion

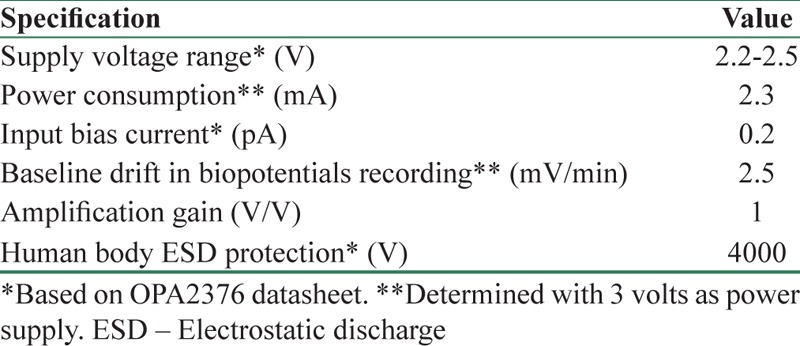

The experiments demonstrated that the new active dry electrodes had a good performance in recording ECG and EEG in a long time with a significantly lower 50 Hz noise power and easier installation procedure rather than conventional wet electrodes. Signals recorded by the proposed electrodes were more stable over the time, except that they had more baseline drift. However, the drift can be easily removed by analog or digital filters. Table 3 summarizes the electrical specification of the new fabricated electrodes.

Table 3.

Electrical specification of an active dry electrode

Another limitation of the dry multipin electrode was its more sensitivity to the electrode's displacements [Figure 11]. An electrode with sharper pins demonstrated better robustness against movements but made the participant feel discomfort. Anyway, the shape of the multipin electrode can be optimized for better performance and smaller size as the next step in this research. Implementation of a high-pass filter inside the active circuit is another option that can be considered in the future designs.

Figure 11.

Baseline fluctuations in electroencephalogram signal caused by movement of the multipin dry electrodes forming a weak electrode-skin contact

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Searle A, Kirkup L. A direct comparison of wet, dry and insulating bioelectric recording electrodes. Physiol Meas. 2000;21:271–83. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/21/2/307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salvo P, Raedt R, Carrette E, Schaubroeck D, Vanfleteren J, Cardon L. A 3D printed dry electrode for ECG/EEG recording. Sens Actuators A Phys. 2012;174:96–102. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao LD, Wang IJ, Chen SF, Chang JY, Lin CT. Design, fabrication and experimental validation of a novel dry-contact sensor for measuring electroencephalography Signals without skin preparation. Sensors. 2011;11:5819–34. doi: 10.3390/s110605819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin CT, Liao LD, Liu YH, Wang IJ, Lin BS, Chang JY. Novel dry polymer foam electrodes for long-term EEG measurement. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2011;58:1200–7. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2010.2102353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YH, Op de Beeck M, Vanderheyden L, Carrette E, Mihajlovic V, Vanstreels K, et al. Soft, comfortable polymer dry electrodes for high quality ECG and EEG recording. Sensors (Basel) 2014;14:23758–80. doi: 10.3390/s141223758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh TI, Yoon S, Kim TE, Wi H, Kim KJ, Woo EJ, et al. Nanofiber web textile dry electrodes for long-term biopotential recording. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst. 2013;7:204–11. doi: 10.1109/TBCAS.2012.2201154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Natarajan M, Govindarajan GT. Design and development of textile electrodes for EEG measurement using copper plated polyester fabrics. J Text Apparel Technol Management. 2014;8:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prutchi D, Norris M. Design and Development of Medical Electronic Instrumentation: A Practical Perspective of the Design, Construction, and Test of Medical Devices. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko WH, editor. Active Electrodes for EEG and Evoked Potential. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 1998 Proceedings of the 20th Annual International Conference of the IEEE; October 29, 1998, November 1. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonseca C, Silva Cunha JP, Martins RE, Ferreira VM, Marques de Sá JP, Barbosa MA, et al. A novel dry active electrode for EEG recording. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2007;54:162–5. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2006.884649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahammed Muneer KV, editor. Non Contact ECG Recording Instrument for Continuous Cardiovascular Monitoring. Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI), 2014 IEEE-EMBS International Conference on; June 1-4. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byeon JG, Jin KS, Park BW. Design of a low-cost active dry electrode module for single channel EEG recording. J Biomed Eng Res. 2005;26:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valchinov ES, Pallikarakis NE. An active electrode for biopotential recording from small localized bio-sources. Biomed Eng Online. 2004;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]