Editor—Several articles about research ethics committees in the issue of 31 July have been constructive in advising about the need for change. Others have been less helpful, especially when based on error or misconception.

Nicholson claimed that research ethics committees may be unable to function because of political control.1 There is not, and never has been, a proposal for “direct political control” of research ethics committee membership. The European Directive on Clinical Trials (directive 2001/20/EC) legally obliges all member states, including the United Kingdom, to “take the measures necessary for establishment and operation of ethics committees.” The newly created United Kingdom Ethics Committee Authority simply comprises the four ministers of the countries in the United Kingdom who have until now been separately responsible for their NHS research ethics committee systems. His claim that results of UK research could not now be used for regulatory purposes is simply unfounded.

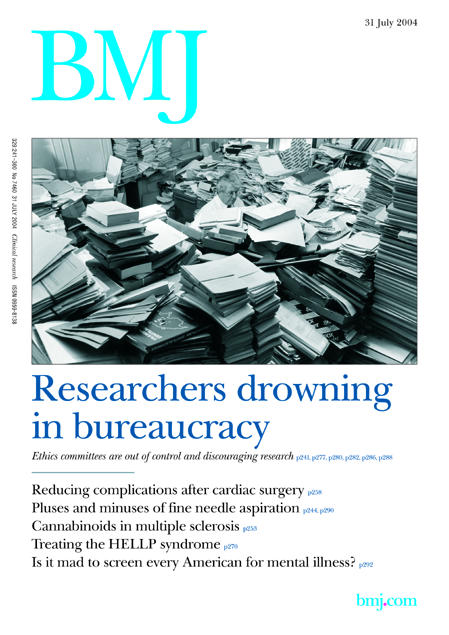

Figure 1.

Ethics committees must be independent of research organisations. This independence relates to their decisions, not their operating processes. Previously some 200 research ethics committees had different processes and forms—a researcher's nightmare. Any research now requires only a single ethical review, irrespective of the number of UK sites involved. All NHS research ethics committees in the United Kingdom increasingly operate in a standard fashion, providing an answer within 60 days. Repeated questions to researchers, which caused great delays, are not now permitted.

The five linked articles in the edition of 31 July nicely expose the dilemmas involved in ethical review of human research. What is ethically acceptable to society? How should research proposals be assessed against this? And how far can we go “at risk” in simplifying the assessment process? Parker et al address the first question, using rare diseases as a case study.2 Such projects often perplex ethics committees, and some informed and intelligent debate can only help. Ward et al offer a useful summary of the issues related to access to individuals and their data in epidemiological research.3 Their project would now require only one application as opposed to the 213 they had to make in 1998.

Jamrozik is initially critical of the new national application form.4 However, his ensuing well-crafted arguments make a good case for a comprehensive assessment of the researcher's understanding of the ethical issues in research. But, as he says, to submit an ideal application, researchers require thorough training in both the methods and the ethical issues relating to research in human subjects or their tissues or data.

His own experience as a research ethics committee member reveals how far we are from this ideal state, and the papers by Wald, and Jones and Bamford serve only to emphasise this.5,6 Wald could have saved himself a lot of time, effort, and phone calls if he had read the “question-specific guidance” published on the COREC web site (http://corec.org.uk). It explains nearly all the questions, and often states what the ethics committee is looking for. He would have found descriptions and URLs for the two reference numbers (ISRCTN and EudraCT) for which he claims no guidance was given.

Many will disagree with his claim that most questions in Part A are not related to ethical review. Conflict of interest of the researcher, indemnity for the protection of participants, and confidentiality of data are widely accepted as core ethical issues. Part B is divided into sections specific to particular activities—for example, use of stored tissue—and for nearly all research, substantial portions of the form are simply not activated, so it is normally far shorter than the maximum 57 pages. Part C assesses the suitability of the local investigator (such as qualifications and research experience) and the adequacy of site facilities. For clinical trials of medicines at least, the ethics committee is now legally obliged to consider them.

Part D was an attempt to be helpful to researchers by unifying the information required by research and development departments. Although now withdrawn, it may yet reappear if the UK research and development community can agree on a nationally acceptable dataset.

Many of the silent majority of several hundred other applicants who have successfully completed applications since the new form was introduced will doubtless have had some problems. However, sensible email enquiries, calls to the helpline, and reference to the question-specific guidance have worked for them. Our strong advice to applicants is to study the form and read the comprehensive advice early on when planning their research, reflect on the ethical requirements, and build them into their plans.

Seeking and updating informed consent is fundamental to good practice in research involving human participants. Jones and Bamford's failure to follow this suggests a need for the sort of training Jamrozik recommends. NHS and university employees have to be held to account for professionalism in research involving patients. It should come as no surprise if research managers intervene over undocumented changes in design or inaccurate consent forms.

No one pretends the current application form or the process is perfect, and it will be regularly reviewed. We welcome constructive criticism at this and any other time. If there is a reasoned case for omitting certain questions from the form or having a different, shorter, process for certain groups of applicants or low risk proposals (as has been suggested by some) then we would like to hear it.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Nicholson R. Another threat to research in the United Kingdom. BMJ 2004;328: 1212-3. (31 July.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parker M, Ashcroft R, Wilkie AOM, Kent A. Ethical review of research into rare genetic disorders. BMJ 2004;329: 288-9. (31 July.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward HJT, Cousens SN, Smith-Bathgate B, Leitch M, Everington D, Will RG, Smith PG. Obstacles to conducting epidemiological research in the UK general population. BMJ 2004;329: 277-9. (31 July.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jamrozik K. Research ethics paperwork: what is the plot we seem to have lost? BMJ 2004;329: 286-7. (31 July.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wald SD. Bureaucracy of ethics applications. BMJ 2002;329: 282-4. (31 July.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones AM, Bamford B. The other face of research governance. BMJ 2004;329: 280-1. (31 July.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]