Abstract

In order to develop clinical diagnostic tools for rapid detection of SARS-CoV (severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus) and to identify candidate proteins for vaccine development, the C-terminal portion of the nucleocapsid (NC) gene was amplified using RT-PCR from the SARS-CoV genome, cloned into a yeast expression vector (pEGH), and expressed as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) and Hisx6 double-tagged fusion protein under the control of an inducible promoter. Western analysis on the purified protein confirmed the expression and purification of the NC fusion proteins from yeast. To determine its antigenicity, the fusion protein was challenged with serum samples from SARS patients and normal controls. The NC fusion protein demonstrated high antigenicity with high specificity, and therefore, it should have great potential in designing clinical diagnostic tools and provide useful information for vaccine development.

Key words: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), coronavirus, nucleocapsid protein, antigenicity, yeast expression system

Introduction

The global outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Year 2003 has posted a great threat to the public health 1., 2., 3.. Recently, several lines of evidence have demonstrated that a new strain of coronaviruses is the causal pathogen of this infectious disease 4., 5., 6.. Some research groups managed to rapidly decode the genome of the virus from couples of clinical isolates worldwide 7., 8., 9., thus, provided the foundation for further analyzing its pathogenicity and the development of effective diagnostic tools and therapeutics.

Coronaviruses produce at least four structural proteins, namely S (spike), M (membrane), E (envelope), and N (nucleocapsid). Antigenicity studies in the avian infectious bronchitis virus indicated that the N protein is one of the immunodominant antigens that induce cross-reactive antibodies in high titers, whereas the S glycoprotein induces serotype-specific and cross-reactive antibodies (10). It has also been reported that the N protein from porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus is the major immunogen of the virus. Several domains of antigenic importance in the N protein were identified by monoclonal antibodies raised against PRRS virus 11., 12., 13.. Interestingly, deletion of the 11 amino acids from the C-terminus of the N protein (NC) disrupted the epitope configuration recognized by all of the conformation-dependent monoclonal antibodies (13); amino acid substitution within the C-terminal domain revealed that the secondary structure of the domain is an important determinant of conformational epitope formation (14).

Wang et al. recently reported that the N protein could be one of the major antigens of SARS-CoV. Specially, two peptides located at the C-terminal region of the N protein of SARS-CoV could be recognized by the antisera from SARS patients (Wang et al., in press). In this study, the coding region of the C-terminal portion of the N protein was cloned as GST-Hisx6 (Glutathione S-transferase Histidine) fusion and the peptide was expressed in yeast. The purified fusion protein showed positive signals when probed with sera from SARS patients in Western analysis. Using the ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) approach, the purified fusion protein was shown to specifically recognize the sera from SARS patients, but not those from the negative controls.

Results

Purification and characterization of the NC fusion protein

The RT-PCR product of the NC segment from Isolate BJ01 was cloned into pGEM-T vector. The recombinant pGEM-T was further PCR amplified with the yeast-cloning primer pair. After verification by DNA sequencing, the PCR product was co-transformed into yeast with the linearized pEGH vector, and the yeast transformants were selected on proper media. The resulting recombinant plasmids were rescued into bacteria, and named as pEGH-NC. The pEGH-NC constructs were restricted with EcoR I to determine whether their inserts were in the right sizes (Figure 1A). Confirmed plasmids were further analyzed with DNA sequencing to validate their identities and reading frames.

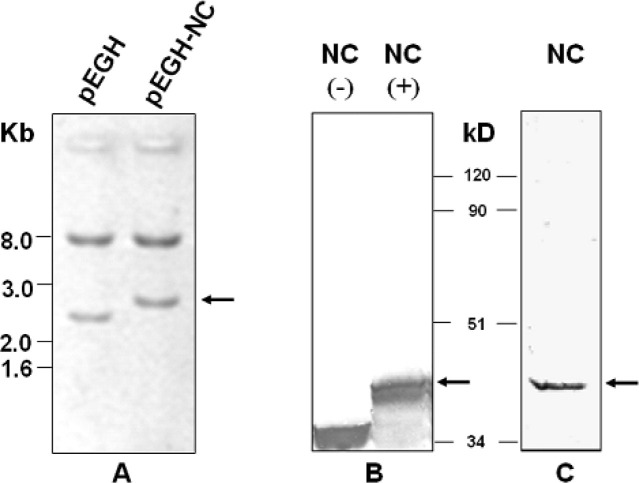

Fig. 1.

Characterization of the NC fragment. A. EcoR I-digested pEGH-NC showed the NC fragment as expected size. B. Western analysis with anti-Hisx6 antibody demonstrated that the NC fragment expressed as the expected molecular weight in the yeast cells with pEGH-NC (+) but not in the control (−). C. The purified NC fusion protein with the GST affinity tag stained by Coomassie Blue. Arrows indicate the expected NC fragment, and the molecular weight markers are indicated.

The confirmed plasmids were re-introduced into yeast cells for the production of the GST-Hisx6-NC fusion protein. Probed with anti-Hisx6 antibodies in a Western analysis, the lysate of the induced yeast cells emerged a band with the expected molecular weight of the fusion protein, which is absent in the control carrying the empty vector, indicating that the NC fragment was specifically expressed in the proper yeast strains (Figure 1B). Using the GST affinity tag, the fusion protein was purified using glutathione agarose beads, and separated by SDS-PAGE (SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis). Coomassie Blue staining (Figure 1C) demonstrated that the fusion protein was purified with high quality and purity without any detectable contamination.

Immunoreactions of the NC fusion protein

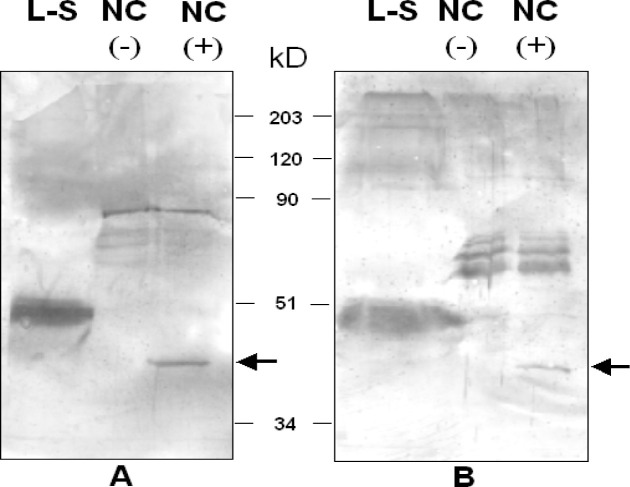

The purified fusion protein was transferred onto a PVDF (Polyvinylidene Fluoride) membrane, probed with antisera from SARS patients, and detected with anti-human IgG secondary antibodies. The results further confirmed the immunoreactivity of the expressed fusion protein (Figure 2), which was immunologically interactive with sera from two individual SARS patients. The GST-His-NC fusion protein gave a specific band different from the normal GST-His fusion protein, and the lysate of Vero-6 cell culture containing SARS-CoV (L-S), as the positive control, showed a strong band of approximately 50 kDa.

Fig. 2.

Immunoreactivity of the purified GST-His-NC fusion protein with antisera from SARS patients. Two independent antisera (A and B) were used for the experiment. Arrows indicate the positions of the GST-His-NC fusion protein. Molecular weights were marked in between the two panels of the blots. L-S: lysate of Vero-6 cell culture containing SARS-CoV.

A potential diagnostic tool for SARS

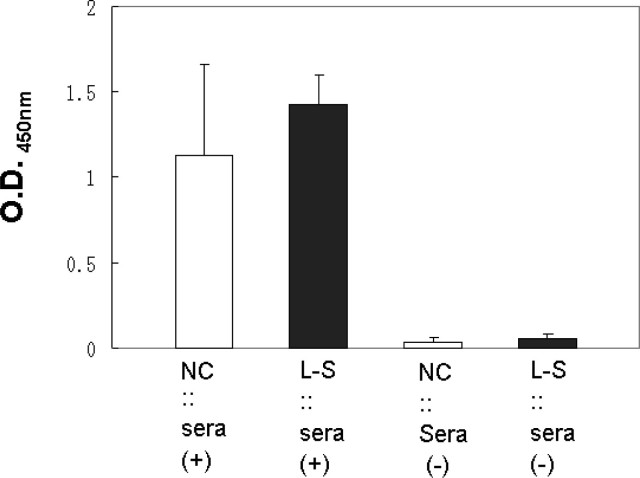

Since the ELISA approach is widely used in clinical diagnostics, we decided to present NC proteins in an ELISA format and determine whether it is useful as a potential detection tool in clinical diagnostics. The purified NC fusion protein was embedded in a 96-well ELISA plate and incubated with the sera taken from four individual SARS patients and four normal controls. The results showed that the NC fusion protein could specifically distinguish the sera from SARS patients (sera +) and those from normal controls (sera −) with a significant statistical difference (Figure 3). In contrast, no significant difference has been observed between the results obtained with the NC fusion protein and with the L-S.

Fig. 3.

ELISA analysis of the NC fusion protein as a potential diagnostic tool against SARS. The O.D. (450 nm) values are indicated as the light bars (the NC fusion protein) and the dark bars (the Vero-6 cell lysate containing SARS-CoV), respectively.

Discussion

The analysis of the structure and function of the N protein in SARS-CoV should be beneficial to understand the life cycle and pathogenicity of the virus (15). Genetically engineered peptides would be one of the best ways to identify the genomic segment associated with the antigenicity and to develop vaccines defended against SARS. Of various methods to overproduce proteins of interest, the yeast system was chosen to express the fusion protein based mainly on two major considerations. First, the cloning procedure is simplified by taking advantage of the homologous recombination cloning strategy in yeast because it is a restriction and ligation reaction-free system, which remarkably simplifies cloning procedures. Secondly, most posttranslational modifications, such as glycosylation and phosphorylation, could be reserved in the eukaryotic expression system (16). These properties may play an important role in immunoreaction. Our data provided firm evidence that the antigenicity of the N protein was well preserved in the NC fusion protein.

The N gene is located towards the 3′ terminal part of the SARS-CoV genome. According to the “coterminal model” that all the subgenomic RNA transcripts have the same 3′ part at its end with the same polyadenylation site (7), the number of transcripts of the N protein would be dramatically larger than all the upstream genes. This model was established for other coronaviruses and recently confirmed by Northern analysis of the SARS-CoV-containing Vero-6 cells using a 3′ terminal probe (7). If the co-terminal model is correct, the N gene in all other 3′ co-terminal subgenomic transcripts would be translated into huge amount of the N protein in addition to the N-specific transcripts, unless a possible mechanism stop or inhibit the ribosome binding site of the gene from translation with the subgenomic transcripts.

It is obvious that when the virus invades the host cells, it may not carry any N proteins outside the virions, even though a specific or non-specific attachment could not be easily excluded. There are only two possible reasons why the N protein is freely exposed to the host immune system. First, the virus collapses after injecting its genome into the host cells. Second, the extra N protein, after binding to the genomic RNA in a fixed molecular ratio, would not be packaged by the cellular liquid bilayer membrane and therefore remains in the cytoplasm. When the host cells collapse, the N protein is released. The most possible mechanism is that the N protein is engulfed by the antigen presenting cells (APC) and presented to T cells for the adaptive immunity. Whether the N protein is involved in the process of the innate immunity remains to be revealed.

Since the N protein has been shown important in many ways, we decided to focus on this protein as an initial step towards better understanding of the mechanism(s) of the disease. Using yeast recombination cloning strategy, we were able to rapidly clone and purify the C-terminal fragment of the N protein from yeast cells. Both Western and ELISA analyses demonstrated that the N protein fragment render highly specific immuno-response in the SARS patients. The ultimate goal of our study is to provide new tools for the campaign against SARS. The cloning and expression of the antigenic fragment of the virus is more advantageous and safer than the method using the whole virus lysate in large-scale production of the antigen and vaccine. The immunoreaction of the NC fusion protein with SARS sera indicates that the NC fusion protein may be of great potential in designing clinical diagnostic tool for the rapid and on-site identification of SARS patients, and further more, may become a candidate for the vaccine against SARS.

Materials and Methods

The sera from SARS patients and normal controls were provided by the Department of Immunoassay, Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI). The Vero-6 cell lysate containing coronaviruses was kindly provided by Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology, Chinese Academy of Militarily Medical Sciences. Yeast Strain Y258 and the yeast expression vector, pEGH, were gifts from Dr. Michael Snyder at Yale University.

Primer design and fragment cloning

The NC-specific primer pair (NCF: AAAGGACAAAAAGAAAAAGACT; NCR: AATTTTACACATTAGGGCTCTTC), corresponding to the segment between Codons 371 and 422 in the N gene, was designed based on the consensus sequences of Isolates BJ01-BJ04 of SARS-CoV contributed by BGI (GenBank accession numbers: AY278488; AY278487; AY278490; AY279354). The nucleotide positions (29,211-29,369) refer to the complete genome sequence of BJ01. The yeast-cloning primer pair was designed by attaching the vector sequences of pEGH to the gene-specific priming sites as described by Zhu et al. (17), and synthesized by Shanghai DNA BioTechnologies Company.

The extraction of viral RNA, RT-PCR, the cloning of PCR product into pGEM-T plasmid, yeast culture and competent cell preparation, transformation, and plasmid rescue were performed as described previously 18., 19.. Briefly, the RT-PCR product was amplified using the NC primer pair and cloned into pGEM-T. The recombinant pGEM-T plasmid was used as the template for PCR with the yeast-cloning primer pair, and the PCR product was co-transformed into yeast competent cells with HindIII/XbaI-linearized pEGH vector (17). The correct reading frame in the recombinant vector was confirmed by sequencing through the junction between the vector and insert. The induction, expression and purification of the fusion protein were carried out following the standard protocol (17).

Western blot and ELISA analysis

Protein extracted from yeast cells were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with milk, rinsed twice with TTBS (Tris 100 mM, NaCl 120 mM, 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.9) and incubated in TTBS with 3% BSA containing either anti-Hisx6 (Pierce, Rockford, USA) or sera from SARS patients as primary antibody at room temperature for 2 h or at 4°C overnight. After the membranes were washed with TTBS three times (5 min each), the secondary antibody was added in TTBS with 3% BSA at room temperature for 1 h. Alkaline phosphatase labeled anti-rabbit IgG (Pierce) and goat anti-human IgG (Beijing Zhongshan Company) were used as secondary antibody to detect Hisx6 and human antibodies, respectively. The results were visualized by incubating the membrane with the mixture of NBT and BCIP (Promega, Madison, USA) for 5-10 min.

ELISA experiments were carried out using conventional protocol. In brief, the purified fusion protein was mixed with sample dilution buffer, embedded in a 96-well ELISA plate, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The wells were then washed five times with washing buffer, and incubated with sera from either SARS patients or normal controls. Working enzyme tracer was added into each well to monitor the binding of the fusion protein and antibodies. The signals were then detected at 450 nm by an ELISA reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ministry of Science and Technology of China, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and National Natural Science Foundation of China for financial supports. We are indebted to collaborators and clinicians from Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology in Chinese Academy of Militarily Medical Sciences, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, National Center of Disease Control of China, and the Municipal Governments of Beijing and Hangzhou.

Contributor Information

Heng Zhu, Email: zhuh@genomics.org.cn.

Huanming Yang, Email: yanghm@genomics.org.cn.

References

- 1.Poutanen S.M. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee N. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke T. SARS hits hard: death rates higher than expected, but control measures seem to be working. Nature. 2003 www.nature.com/nsu/030505/030505-4.html [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peiris J. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ksiazek T.G. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drosten, C., et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348: 1967–1976. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Rota P.A. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marra M.A. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300:1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin E.D. A complete sequence and comparative analysis of a SARS-associated virus (Isolate BJ01) Chin. Sci. Bull. 2003;48:941–948. doi: 10.1007/BF03184203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ignjatovic J., Galli L. Structural proteins of avian infectious bronchitis virus: role in immunity and protection. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1993;342:449–453. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2996-5_71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meulenberg J.J. Localization and fine mapping of antigenic sites on the nucleocapsid protein N of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus with monoclonal antibodies. Virology. 1998;252:106–114. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez M.J. Epitope mapping of the nucleocapsid protein of European and North American isolates of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1997;78:2269–2278. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-9-2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wootton S.K. Antigenic structure of the nucleocapsid protein of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 1998;5:773–779. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.6.773-779.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wootton S. Antigenic importance of the carboxy-terminal beta-strand of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nucleocapsid protein. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2001;8:598–603. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.3.598-603.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavanagh D., Brown T.D.K. Structure and function studies of the nucleocapsid protein of mouse hepatitis virus. Plenum Press; New York, USA: 1990. Coronavirus and their diseases; pp. 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell D.A. Vector for the inducible overexpression of glutathione S-transferase fusion protein in yeast. Yeast. 1993;9:715–723. doi: 10.1002/yea.320090705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu H. Global analysis of protein activities using Proteome chips. Science. 2001;293:2101–2105. doi: 10.1126/science.1062191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook J. Third Edition. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York, USA: 2000. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burke D. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York, USA: 2000. Methods in yeast genetics. [Google Scholar]