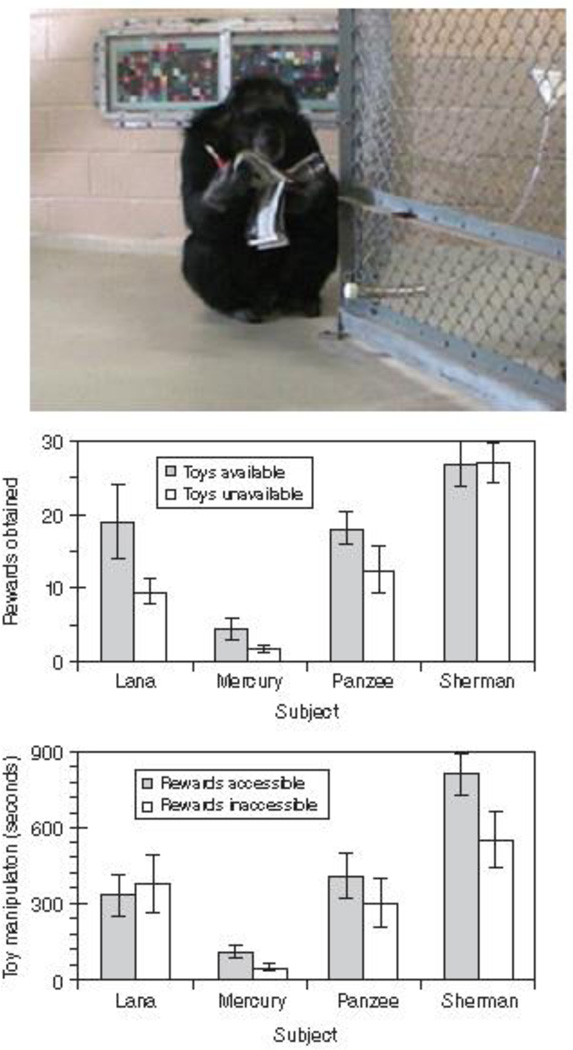

Figure 11.

The top panel shows chimpanzee Sherman with items he could use for self-distraction during an accumulation self-control test. An automated dispenser delivered food items, one-at-a-time, into the tube that projected into his enclosure. Food items would continue to accumulate as long as Sherman did not take the tube and eat the items. The middle panel shows that three of four chimpanzees obtained more food items when they had toys to act as distractions than when they did not. However, this result is the not the critical one to showing self-distraction, because it may have been that simply having toys made chimpanzees play with the more, and thus wait longer. The bottom panel shows the crucial result. Three chimpanzees showed a statistically greater level of item manipulation when rewards were accessible (i.e., they had to self-impose the continued delay of eating those items) than when rewards were inaccessible and delay was imposed by the experimenters. This meant that having toys available was not the key factor in whether chimpanzees interacted with those toys. The key factor was whether the chimpanzees had to maintain self-control in the face of temptation or did not. These data are reported in Evans and Beran (2007)181.