Abstract

Lake Tanganyika is well-known for its high species-richness and rapid radiation processes. Its assemblage of cichlid fishes recently gained momentum as a framework to study parasite ecology and evolution. It offers a rare chance to investigate the influence of a deepwater lifestyle in a freshwater fish-parasite system. Our study represents the first investigation of parasite intraspecific genetic structure related to host specificity in the lake. It focused on the monogenean flatworm Cichlidogyrus casuarinus infecting deepwater cichlids belonging to Bathybates and Hemibates. Morphological examination of C. casuarinus had previously suggested a broad host range, while the lake’s other Cichlidogyrus species are usually host specific. However, ongoing speciation or cryptic diversity could not be excluded. To distinguish between these hypotheses, we analysed intraspecific diversity of C. casuarinus. Monogeneans from nearly all representatives of the host genera were examined using morphometrics, geomorphometrics and genetics. We confirmed the low host-specificity of C. casuarinus based on morphology and nuclear DNA. Yet, intraspecific variation of sclerotized structures was observed. Nevertheless, the highly variable mitochondrial DNA indicated recent population expansion, but no ongoing parasite speciation, confirming, for the first time in freshwater, reduced parasite host specificity in the deepwater realm, probably an adaptation to low host availability.

Host specificity is one of the basic biological factors influencing the life cycle and diversity of parasitic organisms1. It is highly variable among groups and within taxa, ranging from strict specialist to generalist species, but always limited by the occurrence of potential hosts2. Host specificity is characterised by a trade-off of costs and benefits. While specialists have evolved specific adaptations to their host and therefore maximise profits, generalist species infecting a broad range of hosts are less affected by possible host extinction.

But to what extent is this important aspect of parasite biodiversity dependent on host ecology? The capability of a parasite to infect a host is determined by their co-evolutionary history and also ecological determinants such as host species longevity, stability and seasonality of a particular ecosystem. However, it seems that host species’ ecological similarity is more important than host phylogeny3.

Lower host-specificity affected by decreasing host population density in deepwater habitats has been documented in marine environments4,5,6 but never in freshwater systems. Decreased host-specificity in marine pelagic deepwater habitats was proposed to increase the chance of finding a host if host species exhibit low population densities, which is characteristic for most deepwater taxa4,5,6. In the present study we focus on yet unexplored parasite host choice patterns in the non-littoral habitat (i.e. the pelagic and deepwater zone) of one of the biggest and in terms of biodiversity most exceptional freshwater ecosystems in the world.

Lake Tanganyika, situated in the East African Rift Valley, is the second deepest and second oldest lake in the world. It is known for its remarkable species diversity characterised by rapid radiation processes in many vertebrate and invertebrate taxa7, including parasitic flatworms that infect cichlids8. Therefore, it has been intensively studied for many decades. Although the first record of parasitic flatworms in Lake Tanganyika stems from a study on cestodes from 19149, the knowledge about the diversity and role of parasitic organisms in this unique environment is still poor and fragmentary. In the last years, parasitological research in the lake has mainly focused on the monogenean fauna of its cichlids and the number of described species is increasing10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Monogenea van Beneden, 1858 is one of the most species-rich groups of Platyhelminthes19,20 with more than 3,500 already described species21. Most monogeneans are ectoparasites that infect the body or gills of freshwater and marine fishes. One species has a mammalian host and some have also colonised invertebrates or adopted an endoparasitic lifestyle inside fishes, turtles or amphibians22.

The most important attachment organ of monogeneans is the opisthaptor, which is located posteriorly and which contains sclerotized structures such as hooks, clamps or suckers23. The evolutionary expansion of this parasitic group is related to the opisthaptor diversity and its adaptability to different hosts and infection sites24. Whereas the haptoral region is characteristic of species groups or lineages, the morphology of the male copulatory organ (MCO) is important for species-level diagnosis in many groups of Monogenea22. The ecological, behavioural and phylogenetic diversity of cichlid fishes, especially in Lake Tanganyika25,26, make them ideal models for investigating parasite speciation mechanisms such as the influence of host ecology on parasite diversity27,28,29. Cichlids (Teleostei, Cichlidae) form one of the most diverse vertebrate families with around 2,200 known species30. In each of the African Great Lakes, hundreds of endemic species evolved within a short period of time31,32,33,34,35. Currently, 13 monogenean genera are known to infect cichlid species and six of these have been observed on African representatives36. Cichlidogyrus (Monopisthocotylea, Dactylogyridae) is the most species rich, with 102 representatives recorded from 88 different host species10,11,12,13,14,15,18,37,38,39,40,41,42. This genus displays variation in host-specificity and contains generalist but also strictly specialist species39,43. In Lake Tanganyika, most species of Cichlidogyrus described to date are strict or intermediate specialists8,10,12,13,15 following the terminology used in Mendlová & Šimková43. While strict specialists infect only a single host species, intermediate specialists parasitise on two or more congeneric host species and intermediate generalist infect heterogeneric host species from the same tribe. The host range of generalists includes two or more hosts from different tribes. A complete list of Cichlidogyrus species from Lake Tanganyika with their host species is provided in Table 1. It was suggested that the relatively high degree of monogenean host-specificity is the result of adaptive processes related to their direct life cycle and to the tight co-evolutionary interactions with their hosts24,44,45, depending on the species-specific response to both mechanical structures and the chemical composition of fish tissue46,47. To date, 24 species of Cichlidogyrus have been described from 20 different cichlid host species from Lake Tanganyika10,11,12,13,14,15,18. Only three of these have been reported from the benthopelagic and truly pelagic deepwater environment: Cichlidogyrus brunnensis, C. attenboroughi Kmentová, Gelnar, Koblmüller & Vanhove, 2016 and C. casuarinus Pariselle, Muterezi Bukinga & Vanhove, 2015. The present study focuses on exploring the intraspecific diversity of C. casuarinus infecting two deepwater cichlid genera, Bathybates Boulenger, 1898 and Hemibates Regan, 1920. These genera constitute the endemic tribe Bathybatini Poll, 1986. Until recently, also the genus Trematocara was included in the tribe48, but genome-wide data49 suggest that Poll’s52 original classification into Bathybatini, comprising the genera Bathybates and Hemibates, and Trematocarini, consisting of Trematocara, is more reasonable than alternative classifications34,48,51,53. The tribe Bathybatini contains eight currently recognised benthopelagic and truly pelagic species in two deeply divergent genera48,49,53 (see Fig. 1). Whereas Bathybates species are chiefly piscivorous, Hemibates has a broader diet that also includes shrimps. With the exceptions of B. ferox, which has not been recorded below 70 meters and B. horni, of which no information is available, all species within these two genera have maximal recorded depth ranges ranging from 160 down to 210 meters. Hence, some of these species occur just above the lake’s anoxic zone54. Morphological and genetic data were collected to test the hypothesis of Pariselle et al.15, who suggested that Cichlidogyrus casuarinus has a broader host range than its congeners in Lake Tanganyika because it infects pelagic deepwater hosts. Here, the Cichlidogyrus host-specificity in the deepwater habitat in Lake Tanganyika is tested for all fish hosts within the presumed host range of C. casuarinus, potentially the first intermediate generalist of Cichlidogyrus reported for Lake Tanganyika (see Table 1), on a lake-wide geographical scale. However, in other monogeneans there are reports of cryptic speciation, with allegedly generalist monogeneans representing a complex of more host-specific cryptic species28 or incipient speciation, with haplotypes or morphotypes of the same generalist species preferring a certain host species55. These scenarios can only be verified by studying C. casuarinus at the intraspecific level. There are only few studies about African monogeneans focusing on intraspecific aspects56. Here, the Cichlidogyrus host-specificity in the non-littoral habitat in Lake Tanganyika is tested for all fish species within the presumed host genera of C. casuarinus and on a lake-wide geographical scale. Multivariate statistic approaches of morphological characters and genetic characterisation using markers with different rates of molecular evolution were used to answer the following questions:

How broad is the host range of this parasite species among members of the Bathybatini?

Is there any morphological intraspecific variation?

Does the apparently broad host range of Cichlidogyrus casuarinus infecting Bathybates and Hemibates reflect cryptic speciation or a lack of host preference?

What is the population structure and recent demographic history of this deepwater species of Cichlidogyrus?

Table 1. List of the 24 monogenean species of Cichlidogyrus reported in Lake Tanganyika with host specification10,12,14,15,42,112,113.

| Monogenean species | Host species | Host-specificity43 |

|---|---|---|

| Cichlidogyrus. attenboroughi Kmentová, Gelnar, Koblmüller & Vanhove, 2016 | Benthochromis horii Poll, 1948 | strict specialist |

| C. banyankimbonai Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015 | Simochromis diagramma (Günther, 1894) | strict specialist |

| C. brunnensis Kmentová, Gelnar, Koblmüller & Vanhove, 2016 | Trematocara unimaculatum Boulenger, 1901 | strict specialist |

| C. buescheri Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015 | Interochromis loocki (Poll, 1949) | strict specialist |

| C. casuarinus Pariselle, Muterezi Bukinga & Vanhove, 2015 | Bathybates minor Boulenger, 1906; B. fasciatus Boulenger, 1901; B. vittatus Boulenger, 1914 Potentially also on B. leo Poll, 1956 and Hemibates stenosoma (Boulenger, 1901) | intermediate generalist? |

| C. centesimus Vanhove, Volckaert & Pariselle, 2011 | Ophthalmotilapia ventralis (Boulenger, 1898); O. nasuta (Poll & Matthes, 1962); O. boops (Boulenger, 1901) | intermediate specialist |

| C. frankwillemsi Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015 | Pseudosimochromis curvifrons (Poll, 1942) | strict specialist |

| C. franswittei Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015 | P. marginatus (Poll, 1956); P. curvifrons | intermediate specialist |

| C. georgesmertensi Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015 | P. babaulti (Pellegrin, 1927) | strict specialist |

| C. gillardinae Muterezi Bukinga, Vanhove, Van Steenberge & Pariselle, 2012 | Astatotilapia burtoni (Günther, 1894) | strict specialist |

| C. gistelincki Gillardin, Vanhove, Pariselle, Huyse & Volckaert, 2012 | Ctenochromis horei (Günther, 1894) | strict specialist |

| C. irenae Gillardin, Vanhove, Pariselle, Huyse & Volckaert, 2012 | Gnathochromis pfefferi (Boulenger, 1898) | strict specialist |

| C. makasai Vanhove, Volckaert & Pariselle, 2011 | Opthalmotilapia ventralis (Boulenger, 1898); O. nasuta (Poll Matthes, 1932); O. boops (Boulenger, 1901) | intermediate specialist |

| C. mbirizei Muterezi Bukinga, Vanhove, Van Steenberge & Pariselle, 2012 | Oreochromis tanganicae (Günther, 1894), O. niloticus, O. mossambicus | intermediate specialist |

| C. mulimbwai Muterezi Bukinga, Vanhove, Van Steenberge & Pariselle, 2012 | Tylochromis polylepis (Boulenger, 1900) | strict speciliast |

| C. muterezii Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015 | S. diagramma | strict specialist |

| C. muzumanii Muterezi Bukinga, Vanhove, Van Steenberge & Pariselle, 2012 | T. polylepis | strict specialist |

| C. nshomboi Muterezi Bukinga, Vanhove, Van Steenberge & Pariselle, 2012 | Boulengerochromis microlepis (Boulenger, 1899) | strict specialist |

| C. raeymaekersi Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015 | S. diagramma | strict specialist |

| C. schreyenbrichardorum Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015 | I. loocki | strict specialist |

| C. steenbergei Gillardin, Vanhove, Pariselle, Huyse & Volckaert, 2012 | Limnotilapia dardennii (Boulenger, 1899) | strict specialist |

| C. sturmbaueri Vanhove, Volckaert & Pariselle, 2011 | O. ventralis; O. nasuta | intermediate specialist |

| C. vandekerkhovei Vanhove, Volckaert & Pariselle, 2011 | O. ventralis; O. nasuta; O. boops | intermediate specialist |

| C. vealli Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015 | I. loocki | strict specialist |

Terminology: Strict specialist – infecting only a single host species, intermediate specialist – infecting two or more congeneric host species, intermediate generalist – infecting non-congeneric host species from the same tribe, generalist – infecting two or more hosts from different tribes.

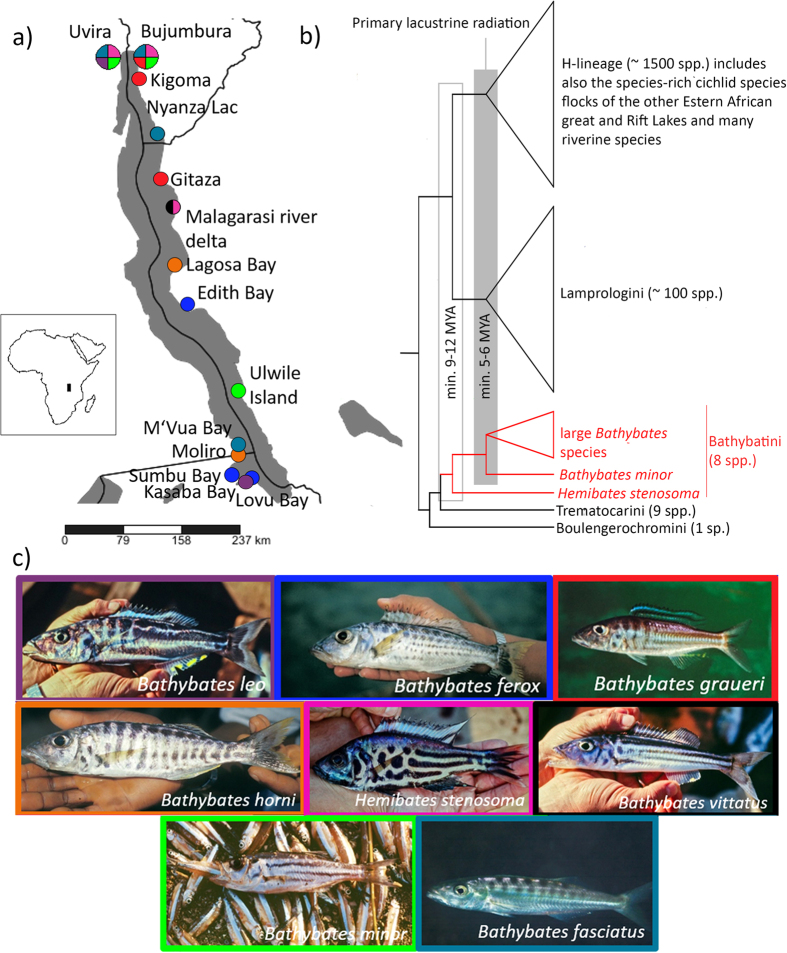

Figure 1. Host species information.

(a) Geographical positions of sampling localities in Lake Tanganyika with indication of host species (pictures by Ad Konings). (b) Schematic phylogenetic tree of the Lake Tanganyika cichlid radiation, showing the phylogenetic position and relative divergence of the tribe Bathybatini and its major lineages48,50,52. (c) Host species pictures (Ad Konings). The map was created using SimpleMappr software v7.0.0. (available at http://www.simplemappr.net. Accessed February 20, 2016).

Results

Morphological species identification

In total, 764 Cichlidogyrus specimens were retrieved and identified from 24 fish specimens belonging to six host species, namely B. leo Poll, 1956, B. minor Boulenger, 1906, B. horni Steindachner, 1911, B. vittatus Boulenger, 1914, B. fasciatus Boulenger, 1901 and H. stenosoma (Boulenger, 1901), making use of fresh material from an expedition in 2013 and of the historical ichthyological collections of the Royal Museum for Central Africa (Tervuren, Belgium) (Fig. 1; Table 2). All these Cichlidogyrus specimens were collected from the hosts’ gills. No monogeneans were found on B. graueri Steindachner, 1911 and B. ferox Boulenger, 1898. The overall prevalence on most of the species was 100%. The lowest prevalence was recorded on B. leo (25%). Infection intensity ranged from 1 to 263 individuals per gill chamber. This parameter was counted only for one gill chamber as one side needed to remain undamaged in museum specimens. Infection parameters are detailed in Table 2. They are only indicative because of the small sample size. All Cichlidogyrus specimens were identified as C. casuarinus based on the original description15 according to the corresponding shape and measurements of haptoral and male genital hardparts. The often slightly wider range of measurements is interpreted as a logical consequence of a larger sample size and the wider host and geographical range of the measured individuals (Table 3).

Table 2. An overview of host spe cies examined for Cichlidogyrus parasites with localities and infection parameters.

| Host species (host maximum size68, cm) | Locality (geographic coordinates) | Locality – basins57 (date of sampling) | Number of fish specimens (accession number in RMCA) | Number of Cichlidogyrus individuals (accession numbers in RMCA) | Prevalence (%) | Infection intensity/one gill chamber | Abundance (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bathybates fasciatus (39, 7) | Uvira (3°22′S 29°08′E) | The northern basin (9/9/2013) | 1 (MRAC 2016-22-P) | 12 (MRAC 37926-8) | 100 | 6 | 6 |

| Bujumbura (3°23′S 29°22′E) | The northern basin (4/9/2013) | 3 (MRAC 2016-22-P) | 42 (MRAC 37921-5) | 100 | 7.7 | 7.7 (1–19) | |

| M’Vua Bay (08°05′S-30°34′E) | The southern basin (23/3/1947) | 2 (MRAC 112235-242 A, 115) | 3 (MRAC 37898-9) | 50 | 1.5 | 1.5 (0–3) | |

| Nyanza Lac (04°20′S-29°35′E) | The northern basin (1/1/1937) | 3 (MRAC 54746-60 A, B, C) | 7 (MRAC 37900-3) | 66.6 | 3.5 | 2.3 (0–4) | |

| Bathybates horni (27, 2) | Moliro (08°13′S-30°35′E) | The southern basin (12/3/1947) | 1 (MRAC 112481) | 263 (MRAC 37847, 49-73) | 10 | 263 | 263 |

| Lagosa Bay (05°57′S-29°51′E) | The central basin (11/4/1947) | 1 (MRAC 112484) | 162 (MRAC 37827-46, 48) | 100 | 162 | 162 | |

| Bathybates leo (26, 0) | Uvira | The northern basin (9/9/2013) | 4 (−) | 2 (MRAC 37758-9) | 25 | 1 | 162 |

| Kasaba Bay (-08°31′S-30°39′E) | The southern basin (23/11/1995) | 2 (MRAC 99-31P-896-904) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| near Malagarasi River delta (05°14′S-29°45′E and 05°13′S-29°43′E) | The northern basin (26/2/1947) | 1 (112492-496) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Bathybates minor (20, 5) | Bujumbura | The northern basin (4/9/2013) | 7 (MRAC 2016-22-P) | 50 (MRAC 37904-8) | 71.4 | 5 | 3.55 (0–9.5) |

| Ulwile Island (07°25′ S-30°34′ E) | The central basin (4/9/2013) | 1 (2016-22-P) | 8 (MRAC 37909-14) | 100 | 4 | 4 | |

| Bathybates ferox (38, 5) | Sumbu Bay (08°31′S-30°29′E) | The southern basin (31/3/1947) | 3 (MRAC 112187-97 A, B, F) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lovu Bay (08°34′S-30°44′E) | The southern basin (26/3/1947) | 1 (MRAC 112175-80) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Edith Bay (06°30′S-29°55′E) | The central basin (14/2/1947) | 3 (MRAC 112152-62 A, B, C) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hemibates stenosoma (26, 0) | Bujumbura | The northern basin (25/9/2013) | 4 (MRAC 2016-22-P) | 28 (MRAC 37915-6) | 75 | 4.7 | 3.5 (0–8) |

| Uvira | The northern basin (9/9/2013) | 4 (MRAC 2016-22-P) | 36 (MRAC 37917-20) | 100 | 4.5 | 4.5 (2.5–7.5) | |

| near Malagarasi River delta | The northern basin (22/5/1947) | 1 (MRAC 112136) | 27 (MRAC 37891-7) | 100 | 27 | 27 | |

| Bathybates viitatus (42, 0) | near Malagarasi River delta | The northern basin (26/2/1947) | 1 (MRAC 112489) | 124 (MRAC 37874-90) | 100 | 124 | 124 |

| Bathybates graueri (30, 0) | Bujumbura | The northern basin (25/9/2013) | 7 (MRAC 2016-22-P) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Uvira | The northern basin (9/9/2013) | 6 (MRAC 2016-22-P) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Kigoma (04°52′S- 29°38′E) | The northern basin (10/1/1947) | 3 (MRAC 112430-452) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gitaza (03°37′ S-29°20′E) | The northern basin (20/10/1995) | 1 (MRAC 95-98-P-253-62) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 3. Comparison of measurements performed on C. casuarinus haptoral and genital hardparts between the present study and the original description15 (a – mean value ± standard deviation, b – range).

| Parameters (μm) | C. casuarinus (n = 182) | C. casuarinus Pariselle et al.15 (n = 35) |

|---|---|---|

| Total length | 628.7 ± 93.2a (n = 83); (379.1–1003.4)b | 915 (n = 19); (766–1105) |

| Ventral anchor | ||

| Total length | 51 ± 4.7 (n = 158); (38.3–62.5) | 51 ± 2.5 (n = 35); (47–59) |

| Length to notch | 41.7 ± 3.8 (n = 157); (32.1–49.9) | 43 ± 1.7 (n = 35); (39–47) |

| Inner root length | 16.4 ± 2.6 (n = 156); (10.1–21.6) | 17 ± 1.6 (n = 35); (12–19) |

| Outer root length | 9.5 ± 2 (n = 154); (5.1–17.3) | 8 ± 1.5 (n = 35); (5–11) |

| Point length | 16.3 ± 2.1 (n = 157); (10.9–22.8) | 16 ± 1.5 (n = 35); (12–20) |

| Dorsal anchor | ||

| Total length | 56.7 ± 5.5 (n = 156); (40–73.8) | 58 ± 2.8 (n = 32); (52–64) |

| Length to notch | 39.6 ± 3.6 (n = 156); (29.7–46.8) | 40 ± 2.0 (n = 32); (35–44) |

| Inner root length | 22.1 ± 3.1 (n = 156); (15.5–31.3) | 24 ± 1.9 (n = 32); (20–27) |

| Outer root length | 8.4 ± 2 (n = 154); (2.5–14.1) | 8 ± 1.3 (n = 32); (6–11) |

| Point length | 14.2 ± 1.6 (n = 154); (8.9–18.2) | 15 ± 0.8 (n = 32); (13–17) |

| Ventral bar | ||

| Branch length | 64.2 ± 8.3 (n = 157); (43.4–90.3) | 59 ± 3.2 (n = 39); (54–67) |

| Branch maximum width | 9.5 ± 1.8 (n = 164); (5.1–14.5) | 9 (n = 20); (7–12) |

| Dorsal bar | ||

| Maximum straight width | 79.6 ± 13.1 (n = 138); (54.7–115.2) | 71 (n = 20); (64–85) |

| Thickness at midlength | 15.4 ± 3.7 (n = 174); (9.3–39.2) | 15 (n = 15); (12–20) |

| Distance between auricles | 33.7 ± 7 (n = 169); (21.8–55.4) | 30 (n = 20); (23–40) |

| Auricle length | 18.7 ± 3.2 (n = 154); (7.8–28.6) | 17 ± 1.8 (n = 40); (13–23) |

| Hooks | ||

| Pair I | 33.8 ± 4.3 (n = 157); (22–49.4) | 30 ± 1.2 (n = 30); (27–33) |

| Pair II | 22.3 ± 2.6 (n = 129); (11.8–33.5) | — |

| Pair III | 23.7 ± 2.8 (n = 121); (10.6–29.9) | — |

| Pair IV | 25.8 ± 2.7 (n = 111); (13.8–31.2) | — |

| Pair V | 10.8 ± 0.9 (n = 109); (6.2–13.8) | 11 (n = 17); (10–12) |

| Pair VI | 26.3 ± 3.8 (n = 69); (15.9–33.1) | — |

| Pair VII | 27.4 ± 3.6 (n = 64); (14.2–32.5) | — |

| Pair II, III, IV, VI, VII average size | 24.6 ± 3.5 (n = 494); (10.6–33.5) | 23 ± 1.9 (n = 120); (19–28) |

| Copulatory tube straight length | 37 ± 3.1 (n = 163); (29.7–43.2) | 37 (n = 20); (34–44) |

| Accessory piece curved length | 32.8 ± 5.8 (n = 27); (33.1–103.2) | 31 (n = 20); (26–38) |

| Heel straight length | 60 ± 15.7 (n = 157); (25.7–46.9) | 47 (n = 20); (40–59) |

| Vagina curved length | 56.3 ± 12.7 (n = 34); (38.1–83.1) | 46 (36–59) |

| Vagina maximum width | 12 ± 2.2 (n = 49); (7.7–16.5) | 7 (5–8) |

Morphometric and geomorphometric assessment of intraspecific variation

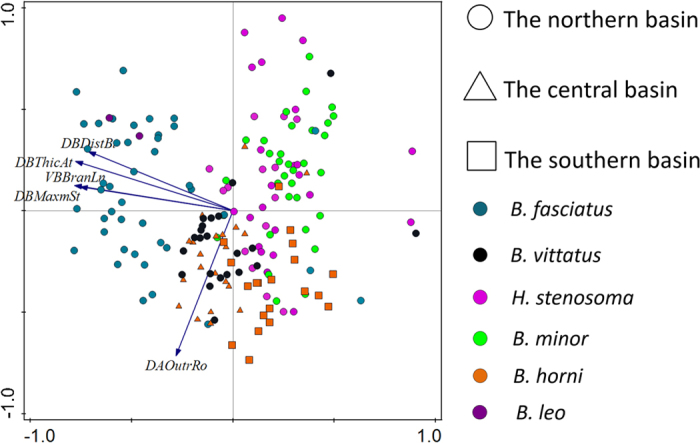

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on measurements taken on the haptoral hardparts of 182 individuals of C. casuarinus to assess intraspecific variation. The first PC explained 60% and the second 11% of the variation in our dataset. The shape of the bars had the highest contribution to PC1 whereas the size of one component of the dorsal anchor (outer root) was the main contributor to PC2. The resultant biplot graph, in which samples were grouped according to host species as well as to the three lake subbasins following Danley et al.57 (Table 2), showed some differentiation according to host species (Fig. 2). Individuals collected from H. stenosoma and B. minor clustered mostly along the positive side of the first axis. Specimens collected from B. fasciatus and B. leo had low values for this axis, with the exception of the three specimens coming from M’Vua Bay (southern basin). Another group was formed by parasites retrieved from B. horni and B. vittatus. These worms displayed lower values for the second axis. Most of the specimens coming from the central and the southern part of the lake displayed low values for the first axis while values for parasites collected in the northern part were widespread across the graph (Fig. 2). However, the fact that data from the central and southern parts of the lake are comprised only by specimens collected from B. horni could have influenced the result. Analyses of variance (ANOVA) provided information about intraspecific variation of C. casuarinus in copulatory tube and heel length (see Supplementary Tables S2 and 5). Box-plot graphs with the length of male copulatory organ structures are showed in Supplementary Figs S1 and S2. The analyses of copulatory tube length were based on 157 individuals while analyses of heel length were based on 149 individuals. Significant differences in copulatory tube length were observed between C. casuarinus from all of the host species except for B. fasciatus and B. vittatus. Comparisons of heel lengths showed a significant difference between C. casuarinus collected from B. fasciatus and the other host species, except for B. vittatus. There was no significant difference among individuals collected from H. stenosoma, B. minor and B. horni. No influence of geographical range was observed on the intraspecific variation in copulatory tube length. Individuals collected from the south of the lake differed significantly in heel length from specimens coming from the north.

Figure 2. A biplot of PCA (first two axes) based on measurements of haptoral sclerotized structures only showing the five best fitting morphological characters selected by CANOCO.

Symbols denote host species and their origin in each of the three subbasins of Lake Tanganyika. DALENGTO – Dorsal anchor, Length to notch, DATotlLn- Dorsal anchor, Total length, DBMaxmSt – Dorsal bar, Maximum straight width, VATotlLn – Ventral anchor, Total length, VBBranLn – Ventral bar, Branch length.

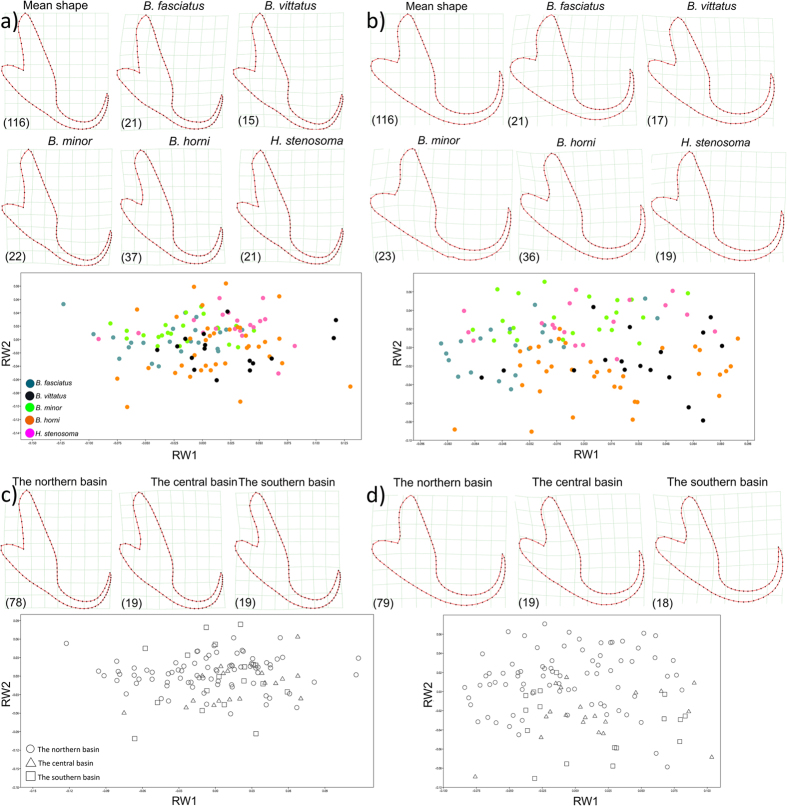

Intraspecific shape plasticity of C. casuarinus was analysed using landmarks and semilandmarks placed on one of the dorsal and ventral anchors. Specimens collected from B. leo were not included in the geomorphometric analysis because only two individuals were available. Scatterplots of relative warps showed some clustering according to host species, mainly along the second axis. Sample distribution along the first axis was caused by allometric effects, which were due to differences in the total size of the structures (individuals collected from B. fasciatus with the smallest ventral/dorsal anchor contrary to C. casuarinus from B. horni with the largest measured structure). Differences in the second axis were caused by variation in the shape of the anchors, for which no size effect could be found. For both analyses, specimens collected from H. stenosoma, B. minor and, to a lesser extent, B. fasciatus had relatively high values for the second axis. Values on the second axis were highly variable for B. horni and B. vittatus for the dorsal anchors, whereas they had low values on this axis for the ventral anchor. Based on the values of the bending energy (see Supplementary Table S6), individuals found on H. stenosoma seemed to have anchors that correspond most with the mean shape of both anchors in the dataset. The most divergent shape was displayed by specimens of C. casuarinus recorded from B. vittatus hosts (Fig. 3). The values for specimens collected in the northern part of Lake Tanganyika clustered mainly in the area with high values for the second relative warp. Specimens coming from southern and central localities tended to have lower values for this axis. This result was most evident in the shape of the ventral anchor but less so for the dorsal anchor (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Scatterplots of the first two relative warps showing shape variation of the dorsal and ventral anchor with deformation grids (thin-plate) depicting mean anchor differences among groups.

Symbols denote host species and sampling localities: (a) dorsal anchor, separation according to the host species; (b) ventral anchor, separation according to the host species; (c) dorsal anchor, separation according to the sampling localities; (d) ventral anchor, separation according to the sampling localities. The number of specimens investigated is indicated in brackets.

Based on the results of scatterplots, we defined two groups. The first was formed by the specimens collected from H. stenosoma, B. minor and B. fasciatus. The specimens recorded from B. horni and B. vittatus hosts were placed in a second group. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests showed significant differences between these groups for both the dorsal (Z1,117 = −3.14122, P < 0.01) and the ventral anchor (Z = −3.59488, P < 0.001). Another test was performed to check for significant geographic differences in anchor shapes, comparing specimens collected in the north of the lake with those collected elsewhere. Whereas a significant difference was found between these groups in the shape of the ventral anchor (Z = −2.3227, P < 0.05), this was not the case for the shape of the dorsal anchor (Z = −1.77484, P > 0.05).

Genetic species identification

All host specimens of which parasites were available for genetic analyses (H. stenosoma, B. minor, B. fasciatus) came from the very northern end of the lake. Genetic species identification of parasites was performed using three nuclear markers (28 S rDNA, 18 S rDNA, ITS-1) generally considered as suitable for monogenean species level determination58,59. The length of the successfully sequenced 28 S rDNA fragment ranged from 641 to 747 base pairs (bp). The 18 S rDNA fragment was 195–482 bp long, while the length of ITS-1 sequences ranged between 141 and 474 bp. In total, 27 sequences of 28 S rDNA and 25 sequences of 18 S + ITS1 rDNA were acquired. The Cichlidogyrus parasites shared an identical haplotype for all three rDNA regions and are hence confirmed to be conspecific. Formaldehyde fixation prevented the use of samples from the historical RMCA collections for the genetic part of this study.

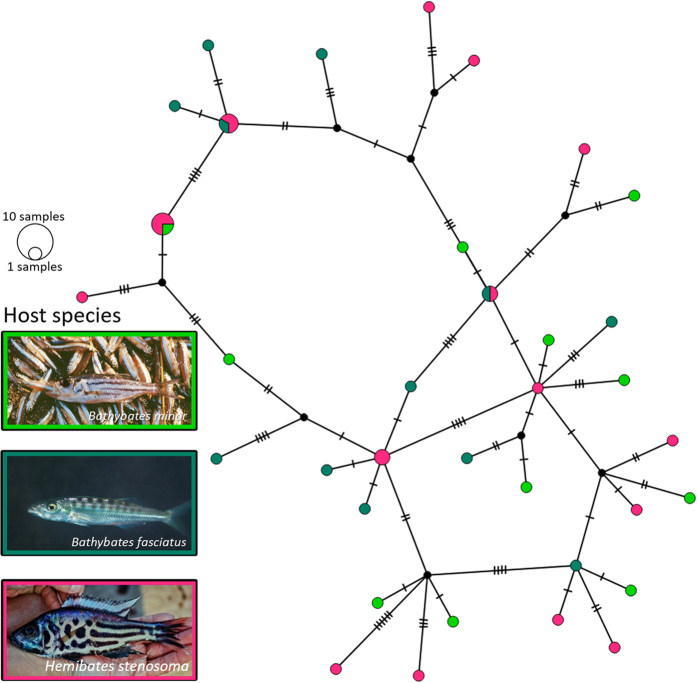

Population structure and past population size trajectories

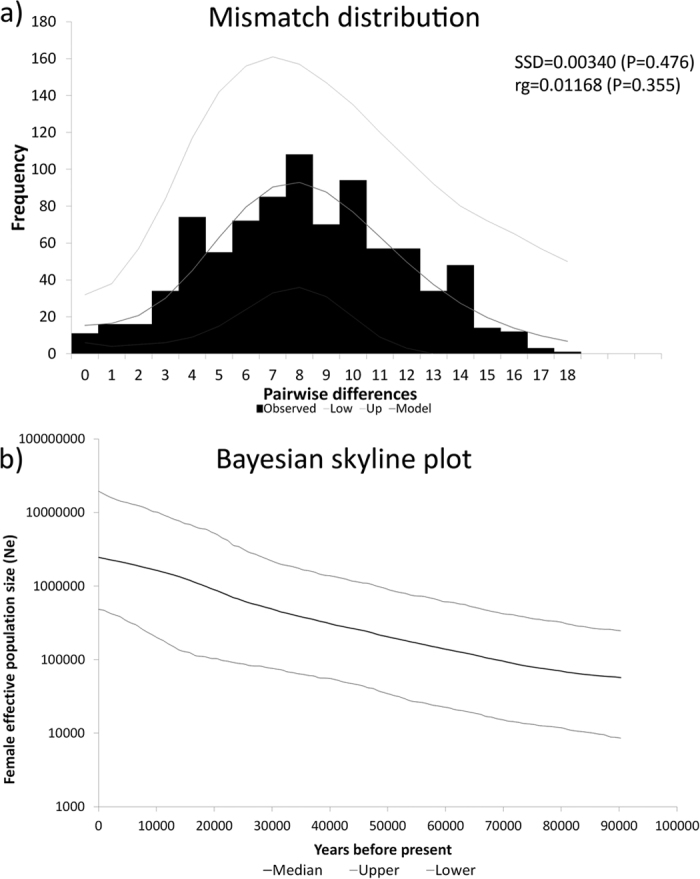

Population structure was assessed using the mitochondrial marker COI. This region was used because of its fast rate of molecular evolution as compared to the nuclear sequences60. Since specimens suitable for DNA extraction were only available from the northern basin, a geographical effect could not be taken into account in the genetic analyses. The length of the COI sequences ranged from 466 to 1120 bp. Sequences for COI mtDNA were obtained from 42 individuals of C. casuarinus collected from three host species (H. stenosoma, B. minor, B. fasciatus), comprising 35 different haplotypes and containing 50 polymorphic sites. Analyses were based on a 402 bp fragment of COI. Haplotype and nucleotide diversity were estimated to be 0.987 and 0.02045, respectively. Genetic distance among haplotypes ranged from 0.2% to 4.7%. The haplotype network representing the relationships among C. casuarinus COI haplotypes is depicted in Fig. 4. There was no evident clustering according to host species and therefore no indication for cryptic diversity or incipient speciation. Moreover, a non-significant FST indicates no barriers between the groups defined by host species (see Supplementary Table S1), at least in northern Lake Tanganyika. The unimodal mismatch distribution with non-significant SSD (SSD = 0.00340, P = 0.476) and rg (rg = 0.01168, P = 0.355) indicated past population expansion of the C. casuarinus population (Fig. 5a). In addition, this result is well supported by the negative and significant value of Fu’s FS (−24.01572, P < 0.001). Tajima’s D was negative, as expected for recent population growth, but not significantly different from zero (−1.03465, P = 0.142), which is probably due to the reduced power of Tajima’s D for detecting population expansion as compared to Fu’s FS61. Also the Bayesian Skyline Plot (BSP; Fig. 5b) indicated that C. casuarinus experienced population expansion in the recent past. The time to the most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) was dated to 144.4 KYA (95% HPD: 92.1–204.1 KYA). The onset of population expansion was dated to 87.0 KYA (95% CI: 51.4–167.0 KYA) based on the parameter τ = 6.994 (95% CI: 4.129–13.428) from the mismatch distribution (τ = 2 μt; where μ is the mutation rate per locus and t is the time since the onset of population growth).

Figure 4. Haplotype network of C. casuarinus COI sequences (n = 42).

The circles represent different haplotypes with size proportional to the number of individuals represented. Haplotypes are connected with lines, indicating number of mutations. Colours correspond with the host species (pictures by Ad Konings).

Figure 5. Demographic history of Cichlidogyrus casuarinus.

(a) Mismatch distribution. The black bars show the observed frequency of pairwise differences. The grey lines refer to the expected distribution based on parameter estimates (plus 95% confidence limits) under a model of population growth. The sum of squared differences (SSD) and raggedness index (rg) and their respective P-values are given to describe the fit of the observed distribution to the expectations based on growth parameter estimates, as well as τ, the modal value of the mismatch distribution. (b) Bayesian skyline plot (BSP) based on 402 base pairs of COI sequences of Cichlidogyrus casuarinus showing the effective populations size through time, assuming a substitution rate of 10% per site per million years. The thick line represents the median values; the thin lines denote 95% highest posterior density (HPD) intervals.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to test for host-specificity of monogeneans in the non-littoral habitat of Lake Tanganyika. Genetic and morphological methods were used to answer questions about the diversity of the monogenean fauna occurring on deepwater fishes. Using multivariate statistical approaches, we investigated the host range and intraspecific variation of Cichlidogyrus casuarinus. Population-level analyses using mtDNA were performed to check whether host preference is driving speciation in C. casuarinus. This also allowed us to infer the species’ demographic history.

The previously proposed low host-specificity of C. casuarinus in the deepwater habitat15, which contrasts with the high host-specificity of many of its congeners in the littoral zone8, was supported by the fact that no variation was observed at the three rDNA regions in C. casuarinus sampled across different host species. Nuclear rDNA regions are considered to be suitable markers for species-level identification of monogeneans59,62. They have been used to show that allegedly generalist Cichlidogyrus species might actually comprise a complex of cryptic species, which are more host-specific than previously assumed28. However, our rDNA data confirm that Cichlidogyrus specimens infecting various bathybatine species are truly conspecific. Hence, we are dealing with an intermediate generalist species, parasitizing on a range of host-species within the same tribe43. Such weak host preference is probably an adaptation to the lower host availability in the deepwater realm, as has been suggested in previous studies on marine systems4,5,6. Therefore, C. casuarinus has evolved a different strategy compared to its congeners in the littoral zone (it is the only generalist species of Cichlidogyrus collected from the lake so far15), by broadening its host range, probably increasing the chance of contact and reducing that of extinction. The host range of C. casuarinus spans Hemibates stenosoma and the whole phylogenetic range of Bathybates. However, there are also species of Bathybates where monogenean infection has not been recorded yet (B. graueri and B. ferox). In Lake Tanganyika, 24 Cichlidogyrus species have already been described from 20 different host species10,11,12,13,14,15,18. Intermediate specialists were recorded in a previous study, namely C. vandekerkhovei, C. makasai, C. centesimus and C. sturmbaueri Vanhove, Volckaert & Pariselle, 2011 recorded from two to three Ophthalmotilapia species13 as well as C. franswittei Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015 infecting two species of Pseudosimochromis14. However, whereas past and/or ongoing hybridisation between Ophthalmotilapia species might explain their shared parasite species65, this does not seem to have been the case in the bathybatines. The divergence between them is ancient (Fig. 1b), and there is no evidence for any past or ongoing interspecific geneflow49,53. Hence, the lower host-specificity of C. casuarinus cannot be attributed to a shallow host phylogeny, confirming its more generalist lifestyle. Close morphological similarity of C. casuarinus with C. nshomboi and C. centesimus, which infect species from other Lake Tanganyika cichlid tribes (Boulengerochromini and Ectodini, respectively), was recorded15. These three monogenean species are the only known representatives of their genus exhibiting a spirally coiled thickening of the wall of the copulatory tube (see also Fannes et al.66). Together, they infect a variety of Tanganyika cichlids, with different feeding and reproductive strategies, occurring in different habitats and belonging to different tribes. This indicates that this morphotype of Cichlidogyrus is characterised by a rather broad niche.

Considering COI is the fastest evolving marker currently available for these monogeneans59, it was used to investigate the intraspecific variability of C. casuarinus in our study. Although the characterisation of C. casuarinus as an intermediate generalist species is well supported by ribosomal DNA, morphometric analyses of haptoral elements showed intraspecific variation, which was linked to host species. Based on the available knowledge about the member species of the Bathybatini, we could not discern a clear link between the morphological differentiation of C. casuarinus and host ecology (e.g., prey and habitat)49,67,68. Host body size and phylogenetic history could explain some of the groupings observed in the analyses of haptoral structures. Individuals collected from H. stenosoma and B. minor, which are the smallest species of the clade68 and which represent more basal lineages49,53, clustered together. Parasites originating from B. horni, B. vittatus, B. leo and B. fasciatus also clustered in our analysis. These host species stem from a phylogenetic lineage that also includes B. ferox and B. graueri49. Our data therefore suggest a correlation between morphological variation in C. casuarinus and the size and phylogenetic position of the host.

The most important morphometric features showing intraspecific variability in our dataset were maximum straight width, thickness at the middle and distance between auricles of the dorsal bar, branch length of the ventral bar and length of the outer root of the dorsal anchor. Although various sclerotized structures (heel length, length of copulatory tube, length of dorsal bar auricle) in other previously described Cichlidogyrus species exhibit a considerable size range10,12,13,15, the range observed in this study is wider. This difference could be explained by the increased geographical range and host range included in the present study compared to the original descriptions of parasites in Lake Tanganyika. Only one previous study13 also looked at some aspects on intraspecific morphometric variability of monogenean species in Lake Tanganyika, demonstrating intraspecific morphological variation of the MCO heel. The greatest infection intensity was observed on two relatively large cichlid species (B. horni and B. vittatus). This confirms the correlation between infection intensity and host body size69. However, individuals from another large host species included in our study, B. fasciatus, were not affected so severely by monogeneans. This discrepancy could be caused by limited sample size (random choice) or by massive infection in certain areas or times (the B. horni and B. vittatus specimens originated from 1949 and were collected at three different localities, see Table 2). In theory, prevalence and infection intensity could help us to identify the original and the more recent hosts of C. casuarinus70,71. Yet, it is hard to reliably quantify such parameters in view of the rarity of several of the host fishes54. Another way to establish which hosts have been colonized earlier would be through (co-)phylogenetic analyses. Although the observed groups based on parasite morphology correspond with the separate position of H. stenosoma and B. minor relative to the other species in the published host phylogeny49,53 unfortunately, our taxon coverage of Bathybatini was only exhaustive for morphological analysis, as museum specimens were unsuitable for molecular work. Moreover, the sequence data generated in this study did not consistently differ between parasites from different host species.

The geomorphometric approach suggested the existence of intraspecific shape variation in both dorsal and ventral anchors. Clustering along the relative warps axes shows almost the same sample distribution according to host species as the PCA of our set of linear haptoral measurements. Phenotypic changes of haptoral sclerites have already been described in many previous studies and are supposed to be influenced by a combination of host characteristics72,73 geographical origin74 and other environmental factors77,78. While some researchers prefer the haptoral region for reconstructing evolutionary history28,58, other investigations devote more attention to the reproductive organs79,80. We found significant intraspecific differences in certain parts of the male copulatory organ between parasites collected from different host species. Although this could be a sign of a possible reproductive barrier, it is known from this morphotype of Lake Tanganyika Cichlidogyrus that heel length can vary substantially within a species13. Moreover, geographic variation of reproductive and haptoral sclerotized structures was found by both morphometric techniques. However, unequal sampling of host species across different basins might have influenced our results. Bathybates minor, B. fasciatus, B. leo, B. vittatus and H. stenosoma were mostly or exclusively collected from the northern part of the lake, whereas the sample of hosts from the central and southern basins was dominated by B. horni.

The observed high haplotype diversity is consistent with a large population size of C. casuarinus81. Non-significant FST estimates suggested a lack of population genetic structure with respect to host species. Equally, there was no indication of ongoing speciation influenced by host preference apparent in the haplotype network. Its non-hierarchical topology indicated the absence of host related population structure. It has been suggested that a broad host range of morphometrically similar monogeneans can result from cryptic speciation processes28,82. However, in that case we should be able to recognise different haplotype variants corresponding with host preference: “choice matters”55. Since the intraspecific genetic variation was independent of host species, no cryptic or incipient speciation was evident in this system. Rather, the observed pattern of morphological variation seemed to be caused by phenotypic changes during ontogenetic development as an adaptation to the host or to the environment. Regarding the differences in MCO morphology, it is unclear how this may be influenced by the host. Poor correlation between genetic and morphometric variation may also be caused by limited sample size, only including COI sequences of C. casuarinus individuals from three host species or by a higher rate of genital morphological changes as compared to mutations in COI55. Even though there is no evidence for population structure according to host species or geographic origin based on COI fragments, future studies employing a large number of unlinked nuclear loci (i.e. generated by next-generation sequencing approaches) might reveal some population structure85,86. However, even if that was the case, it would indicate recent population splitting postdating the ancient divergence of the hosts, since the markers available for this study are generally used to distinguish closely related monogenean populations or species8,55.

Mismatch distribution, BSP and neutrality test all suggested past population expansion of C. casuarinus. These analyses were based on COI sequences and all indicated a recent increase in effective population size. However, only one of the neutrality tests (Fu’s FS) was significant. While Fu’s FS compares expected and observed haplotype diversity and while it is sensitive to demographic expansion87, significantly negative values of Tajima’s D can result from positive selection, a bottleneck, or population expansion88. Compared to other neutrality test statistics, Tajima’s D has considerably lower power to detect population expansion61. Hence the data (non-significant negative D) were still compatible with population expansion. The reported lake level lowstand during the megadraught period ~100 KYA, when the water level dropped by up to 435 m below the present level (which was not enough to separate the lake into its three sub-basins89), reduced the inhabitable lake area considerably, even for pelagic and benthopelagic deepwater fish species. The subsequent lake level rise resulted in an expansion of the available habitat and might have triggered population expansion, a pattern reported for other pelagic and benthopelagic cichlid species from lakes Malawi and Tanganyika90,91. Moreover, recent work suggests congruent population expansion in some of the Bathybatini species (S. Koblmüller, unpublished data). Alternatively, recent host colonization or a bottleneck event might be responsible for the observed pattern55.

The present study is one of the most detailed investigations about intraspecific structure in monogeneans, and the first in an ancient lake. It confirmed the previously suggested decrease of host-specificity in Cichlidogyrus in the non-littoral habitat, with C. casuarinus as the first generalist species of the genus described from the lake. Therefore, it corroborates a pattern also observed in marine systems. There is a trophic relationship between bathybatine cichlids and economically much more important endemic clupeids of Lake Tanganyika’s open water. The predator-prey relationship was already suggested in previous studies to play an important role in host range expansion by transmission of parasites with a direct life cycle92. Therefore, it is recommended to also scrutinise these fisheries target species to assess the diversity and dynamics of parasites in the pelagic zone of this unique freshwater ecosystem. The lack of evidence for genetic population structure related to host preference in C. casuarinus, the significant intraspecific phenotypic plasticity influenced by the host and the reported population expansion of C. casuarinus suggest a high ability of (morphological) adaptation in this monogenean.

Material and Methods

Study area and sampling

Fish specimens (Bathybates leo, B. minor, B. fasciatus, B. graueri and H. stenosoma) were bought at several fish markets in the northern part of Lake Tanganyika, more specifically in the cities of Bujumbura and Uvira. Fishes were identified to the species level in situ. Gills were removed according to the standard protocol of Ergens and Lom93 and immediately preserved in pure ethanol. Some fresh gills were also inspected in situ for monogenean parasites under a stereomicroscope. Protocols were approved by the competent local authorities (mission statement 022/MINEURS/CRH-U/2013) and the Animal Care and Use Committee of Masaryk University, and carried out in accordance with permit CZ01308. To complete the taxon coverage and include geographical variation, fishes from the collection of the Royal Museum for Central Africa (Tervuren, Belgium) were also dissected (B. ferox, B. horni, B. vittatus, B. fasciatus and H. stenosoma) (Table 2, Fig. 1). Monogeneans that were to be used for morphometric analyses were mounted on a slide under a coverslip in Hoyer’s medium94. These specimens were deposited in the invertebrate collection of the RMCA (Table 2). Worms to be used for genetic work were mounted on a slide with a little drop of water under a cover slip after which pictures of the sclerotized structures were taken under phase contrast using an Olympus BX51 microscope and MicroImage analysis software 4.0. This procedure allowed for post hoc species-level identification of specimens of which the entire body was used for DNA extraction. Afterwards, these monogeneans were stored in 1.2 ml eppendorf tubes filled with 99.8% ethanol for subsequent DNA isolation.

Morphometrics and geomorphometrics

Morphological characterization was based on the sclerotized structures of the parasite body; i.e. the opisthaptor and the genital parts. Measurements and photos were taken using an Olympus BX51 microscope with incorporated phase contrast at a magnification of 1000x (objective x100 immersion, ocular x10) with MicroImage 3.1. In total, 26 different features were measured on each individual. The terminology combined Řehulková et al.38 and Pariselle et al.15. To check for within-species variation in haptor morphology, a principal component analysis was performed on linear haptoral measurements of C. casuarinus monogenean parasites from different hosts and localities. For this, the length of pairs of hooks VI and VII was excluded because of the small sample size. This analysis was conducted in CANOCO 5.0195 on the basis of measurements of 21 selected morphological characters of the haptoral region. Missing data were replaced by the average value of each morphological character. ANOVA tests of MCO structures (only when data was available for more than 15 specimens collected per host species/locality) were performed in STATISTICA 12. To take possible geographical intraspecific variation into consideration, samples were also grouped into three basins according to Danley et al.57 (Table 2). The assumption of homogeneous variance within our sample groups was verified by Levene’s test. This prerequisite was only met in the case of the copulatory tube length and for groups defined by host species where Bonferroni’s post-hoc test was performed. Other analyses were therefore conducted using the non-parametric variant, namely Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA (see Supplementary Tables 2 and 5).

Geomorphometric analyses focuses on the visualisation of complex shape variation and provides an additional view to the classical morphometric study (linear measurements)96,97. Since a significant phylogenetic signal in anchor shape was detected in previous studies98, the ventral and dorsal anchors of C. casuarinus were digitalized using landmarks and semi-landmarks with TPSDIG2 software (Rohlf, 2006, TPS package, Stony Brook University). Positions and number of landmarks (5) and semi-landmarks (95) follow Vignon et al.56. Semi-landmarks were distributed in equal intervals. Generalized least square superpositions of landmark and semi-landmark coordinates was computed in TPSRELW (Rohlf, 2006, TPS package, Stony Brook University). The degree of shape deformation was quantified by estimating the minimal shape parameters (relative warps) needed to deform the consensus configuration to each specimen computed from partial warps96,99,100. As above, groups were defined in two ways: according to the host species and to the geographical origin of the specimen. To visualize mean shape anchor differences, thin-plate spline deformation grids were depicted in TPSSpline (Rohlf, 2006, TPS package, Stony Brook University). Parasites collected from B. leo were excluded from the analysis because of the small number of parasite specimens.

Genetic species identification and intraspecific structure

To study the genetic diversity within Cichlidogyrus casuarinus, markers with varying rates of molecular evolution were used. These are: the 18 S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) gene, the 28 S rDNA gene, the first internal transcribed spacer region (ITS-1), and the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (COI) (GenBank accession numbers: 28 S: KX007796-822, 18 S + ITS1: KX007775-95, COI: KX007823-64). Unfortunately, samples from the RMCA collections could not be used in the genetic part of this study because of fixation in formaldehyde. PCR conditions are mentioned in Supplementary Methods.

The analyses of population structure and demographic history within C. casuarinus were based on the COI sequences. COI was used because of its fast rate of molecular evolution as compared to the nuclear markers59,60. This allows for the detection of recent evolutionary events, such as possible incipient speciation as a result of host preference55. The number of haplotypes and polymorphic sites, haplotype diversity and nucleotide diversity101 were calculated using DnaSP 5.1102. Phylogenetic relationships among COI haplotypes were inferred by means of a Median Joining network103 in PopART 1.7104. Differentiation among pre-defined populations (according to host species) was estimated by FST in Arlequin 3.5.1.2105. To test for signals of past population expansion, a mismatch distribution and two different neutrality test statistics, Tajima’s D88 and Fu’s FS106 were calculated in Arlequin. Then the fit of the observed mismatch distribution to the expectations based on growth parameter estimates was evaluated by the sum of squared differences (SSD) and the raggedness index (rg). Significance was assessed with 10,000 permutations. Past population size trajectories were inferred employing a Bayesian coalescent approach (Bayesian skyline tree prior107) as implemented in BEAST 1.8.1108. We employed the model of evolution selected under the Bayesian information criterion in MEGA 6.06, assuming a strict molecular clock and a substitution rate of 10% per million years. Among monogeneans, a substitution rate estimate for COI is only available for Gyrodactylus (13.7–20.0% per million years;109). In view of the short generation time of Gyrodactylus compared to many other monogeneans110, it can be assumed that mutation rates of other monogeneans are somewhat lower111, and that the employed 10% per million years represents a reasonable approximation8. Two independent MCMC runs of 10 million generations each at a sampling frequency of 1,000 were conducted, with a burn-in of the first 10% of sampled generations. The number of grouped intervals was set to 5. Verification of effective sample sizes (ESS > 200 for all parameters), trace of MCMC runs and visualisation of past population size changes were done in Tracer 1.6 (Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Drummond AJ. 2014. Tracer v1.6, available from http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/).

Additional Information

Accession Codes: The sequences obtained were deposited in NCBI GenBank under accession numbers KX007775-864.

How to cite this article: Kmentová, N. et al. Reduced host-specificity in a parasite infecting non-littoral Lake Tanganyika cichlids evidenced by intraspecific morphological and genetic diversity. Sci. Rep. 6, 39605; doi: 10.1038/srep39605 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following people for their contribution to the field work: Andrea Vetešníková-Šimková, Eva Řehulková, Šárka Mašová, Iva Přikrylová, Veronika Nezhybová, Radim Blažek, Gaspard Banyankimbona, Fidel Muterezi Bukinga, Constantin Amundala Shekani, Donatien Muzumani Risasi, Théophile Mulimbwa N’sibula, Joseph Mbirize Ndalozibwa, Axel Meyer, Christian Sturmbauer, Martin Reichard, the Schreyen-Brichard family and the technical staff of Fishes of Burundi. We are grateful to Ad Konings (Cichlid Press) for providing us with fish pictures. Daniel R. Brooks and Walter A. Boeger are acknowledged for useful comments on this study. We also thank Tine Huyse, Jos Snoeks, Miguël Parrent (RMCA) and people in the parasitological group, Masaryk University, Brno for their hospitality and the RMCA for providing access to the collections. Research was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (GBP505/12/G112 – ECIP).

Footnotes

Author Contributions M.P.M.V. designed the study, planned the expedition, contributed to data analyses and interpretation and revised the manuscript. N.K. performed molecular work, analysed sequences, obtained morphometric and geomorphometric data, contributed to data analyses and interpretation and wrote the manuscript. M.G. provided financial support and necessary experience of monogenean taxonomy. M.M. performed molecular work and contributed to alignment of sequences. M.V.S. contributed to geomorphometric analyses and manuscript writing. S.K. identified the hosts, provided background on the host system, performed demographic reconstruction and contributed to expedition planning, data interpretation and manuscript writing. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Vanhove M. P. M. & Huyse T. In Parasite diversity and diversification: evolutionary ecology meets phylogenetics. (eds Morand S., Krasnov B. & Littlewood D. T. J.) 401–419 (Cambridge University Press, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Dunn R. R., Harris N. C., Colwell R. K., Koh L. P. & Sodhi N. S. The sixth mass coextinction: are most endangered species parasites and mutualists? Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 3037–45 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin R. Relative infection levels and taxonomic distances among the host species used by a parasite: insights into parasite specialization. Parasitology 130, 109–115 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoelinck C., Cruaud C. & Justine J. L. Are all species of Pseudorhabdosynochus strictly host specific? - A molecular study. Parasitol. Int. 61, 356–359 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justine J.-L. et al. An annotated list of fish parasites (Isopoda, Copepoda, Monogenea, Digenea, Cestoda, Nematoda) collected from Snappers and Bream (Lutjanidae, Nemipteridae, Caesionidae) in New Caledonia confirms high parasite biodiversity on coral reef fish. Aquat. Biosyst. 8, 22, 10-9063–8–22 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde K. Diversity gradients of marine Monogenea in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Experientia 36, 1368–1369 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Salzburger W., Van Bocxlaer B. & Cohen A. S. Ecology and Evolution of the African Great Lakes and Their Faunas. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 45, 519–545 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Vanhove M. P. M. et al. Hidden biodiversity in an ancient lake: phylogenetic congruence between Lake Tanganyika tropheine cichlids and their monogenean flatworm parasites. Sci. Rep. 5, 13669, 10.1038/srep13669 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Beauchamp P. M. Sur quelques parasites provenant du Congo belge. Revue de Zoologie et de Botanique Africaines 4, 109–116 (1914). [Google Scholar]

- Muterezi Bukinga F., Vanhove M. P. M., Van Steenberge M. & Pariselle A. Ancyrocephalidae (Monogenea) of Lake Tanganyika: III: Cichlidogyrus infecting the world’s biggest cichlid and the non-endemic tribes Haplochromini, Oreochromini and Tylochromini (Teleostei, Cichlidae). Parasitol. Res. 111, 2049–2061 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariselle A. et al. Ancyrocephalidae (Monogenea) of Lake Tanganyika: Does the Cichlidogyrus parasite fauna of Interochromis loocki (Teleostei, Cichlidae) reflect its host’s phylogenetic affinities? Contrib. Zool. 84, 25–38 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Gillardin C., Vanhove M. P. M., Pariselle A., Huyse T. & Volckaert F. A. M. Ancyrocephalidae (Monogenea) of Lake Tanganyika: II: description of the first Cichlidogyrus spp. parasites from Tropheini fish hosts (Teleostei, Cichlidae). Parasitol. Res. 110, 305–313 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhove M. P. M., Volckaert F. A. M. & Pariselle A. Ancyrocephalidae (Monogenea) of Lake Tanganyika: I: Four new species of Cichlidogyrus from Ophthalmotilapia ventralis (Teleostei: Cichlidae), the first record of this parasite family in the basin. Zoologia. 28, 253–263 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Van Steenberge M. et al. Morphology, molecules, and monogenean parasites: an example of an integrative approach to cichlid biodiversity. PLoS One 10, e0124474 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariselle A., Muterezi Bukinga F., Van Steenberge M. & Vanhove M. P. M. Ancyrocephalidae (Monogenea) of Lake Tanganyika: IV: Cichlidogyrus parasitizing species of Bathybatini (Teleostei, Cichlidae): reduced host-specificity in the deepwater realm? Hydrobiologia 748, 99–119 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Grégoir A. F. et al. A link between host dispersal and parasite diversity in two sympatric cichlids of Lake Tanganyika. Freshw. Biol. 60, 323–335 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Vanhove M. P. M., Snoeks J., Volckaert F. A. M. & Huyse T. First description of monogenean parasites in Lake Tanganyika: the cichlid Simochromis diagramma (Teleostei, Cichlidae) harbours a high diversity of Gyrodactylus species (Platyhelminthes, Monogenea). Parasitology 138, 364–80 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kmentová N., Gelnar M., Koblmüller S. & Vanhove M. P. M. Deep-water parasite diversity in Lake Tanganyika: description of two new monogenean species from benthopelagic cichlid fishes. Parasit. Vectors 9, 426, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dušek L., Gelnar M. & Šebelová Š. Biodiversity of parasites in a freshwater environment with respect to pollution: metazoan parasites of chub (Leuciscus cephalus L.) as a model for statistical evaluation. Int. J. Parasitol. 32, 1555–1571 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelnar M., Koubková B., Plánková P. & Jurajda P. Preliminary report of helminths parasitizing fishes of the river Morava with remarks on the effect of water pollution. Helminthologia 31, 47–56 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann K. & Bresciani J. In Fish Diseases and Disorders, Volume 1: Protozoan and Metazoan Infections, Second Edition. (eds Woo P. T. K. & Leatherland J. F.) 297–344 (CAB International, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Pugachev O. N., Gerasev P. I., Gussev A. V., Ergens R. & Khotenowsky I. Guide to Monogenoidea of freshwater fish of Palaeartic and Amur regions. (Ledizione-LediPublishing, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Paperna I. Parasites, infections and diseases of fishes in Africa: An update. (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Kearn G. C. Evolutionary expansion of the Monogenea. Int. J. Parasitol. 24, 1227–1271 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocher T. D. Adaptive evolution and explosive speciation: the cichlid fish model. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 288–298 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblmüller S., Sefc K. M. & Sturmbauer C. The Lake Tanganyika cichlid species assemblage: Recent advances in molecular phylogenetics. Hydrobiologia 615, 5–20 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Pariselle A., Morand S., Deveney M. & Pouyaud L. In Taxonomy, ecology and evolution of metazoan parasites. (eds Combes C. & Jourdan J.) 147–166 (Universitaires de Perpignan, 2003).

- Pouyaud L., Desmarais E., Deveney M. & Pariselle A. Phylogenetic relationships among monogenean gill parasites (Dactylogyridea, Ancyrocephalidae) infesting tilapiine hosts (Cichlidae): Systematic and evolutionary implications. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 38, 241–249 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhove M. P. M. et al. Cichlids: A Host of Opportunities for Evolutionary Parasitology. Trends Parasitol. 32, 820–832 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblmüller S., Albertson R. C., Genner M. J., Sefc K. M. & Takahashi T. Preface: Advances in cichlid research: behavior, ecology, and evolutionary biology. Hydrobiologia 748, 1–5 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Salzburger W. The interaction of sexually and naturally selected traits in the adaptive radiations of cichlid fishes. Mol. Ecol. 18, 169–185 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner G. F. Adaptive radiation of cichlid fish. Curr. Biol. 17, 827–831 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturmbauer C., Husemann M. & Danley P. In Biodiversity Hotspots (eds Zachos F. E. & Habel J. C.) 333–362 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Muschick M., Indermaur A. & Salzburger W. Convergent evolution within an adaptive radiation of cichlid fishes. Curr. Biol. 22, 2362–2368 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T. & Koblmüller S. The adaptive radiation of cichlid fish in Lake Tanganyika: a morphological perspective. Int. J. Evol. Biol. 2011, 620754, 10.4061/2011/620754 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariselle A. et al. The monogenean parasite fauna of cichlids: a potential tool for host biogeography. Int. J. Evol. Biol. 2011, 471480, 10.4061/2011/471480 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariselle A. & Euzet L. Systematic revision of dactylogyridean parasites (Monogenea) from cichlid fishes in Africa, the Levant and Madagascar. Zoosystema 31, 849–898 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Řehulková E., Mendlová M. & Šimková A. Two new species of Cichlidogyrus (Monogenea: Dactylogyridae) parasitizing the gills of African cichlid fishes (Perciformes) from Senegal: Morphometric and molecular characterization. Parasitol. Res. 112, 1399–1410 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariselle A., Bitja Nyom A. R. & Bilong Bilong C. F. Checklist of the ancyrocephalids (Monogenea) parasitizing Tilapia species in Cameroon, with the description of three new species. Zootaxa 3599, 78–86 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariselle A., Bitja Nyom A. R. & Bilong Bilong C. F. Four new species of Cichlidogyrus (Monogenea, Ancyrocephalidae) from Sarotherodon mvogoi and Tylochromis sudanensis (Teleostei, Cichlidae) in Cameroon. Zootaxa 3881, 258–66 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messu Mandeng F. D. et al. A phylogeny of Cichlidogyrus spp. (Monogenea. Dactylogyridea) clarifies a host-switch between fish families and reveals an adaptive component to attachment organ morphology of this parasite genus. Parasit. Vectors 8, 582 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kmentová N., Gelnar M., Koblmüller S. & Vanhove M. P. M. First insights into the diversity of gill monogeneans of ‘Gnathochromis’ and Limnochromis (Teleostei, Cichlidae) in Burundi: do the parasites mirror host ecology and phylogenetic history? PeerJ 4, e1629, 10.7717/peerj.1629 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendlová M. & Šimková A. Evolution of host specificity in monogeneans parasitizing African cichlid fish. Parasit. Vectors 7, 69 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin R. Determinants of host-specificity in parasites of freshwater fishes. Int. J. Parasitol. 22, 753–758 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker S. C. Evolution of host-parasite associations among species of lice and rock-wallabies: Coevolution? Int. J. Parasitol. 21, 497–501 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington I. D., Cribb B. W., Hamwood T. E. & Halliday J. a. Host-specificity of monogenean (platyhelminth) parasites: A role for anterior adhesive areas? Int. J. Parasitol. 30, 305–320 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann K. Interactions between monogenean parasites and their fish hosts. Int. J. Parasitol. 32, 309–319 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T. Systematics of Tanganyikan cichlid fishes (Teleostei: Perciformes). Ichthyol. Res. 50, 367–382 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Kirchberger P. C., Sefc K. M., Sturmbauer C. & Koblmüller S. Evolutionary History of Lake Tanganyika’s Predatory Deepwater Cichlids. Int. J. Evol. Biol. 2012, 716209, 10.1155/2012/716209 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T. & Sota T. A robust phylogeny among major lineages of the East African cichlids. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 100, 234–242 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B. S., Matschiner M. & Salzburger W. A tribal level phylogeny of Lake Tanganyika cichlid fishes based on a genomic multi-marker approach. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 83, 56–71 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poll M. Classification des cichlidae du lac Tanganika. Académie R. Belgique Membres la Cl. des Sci. 45, 1–163 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Koblmüller S., Duftner N., Katongo C., Phiri H. & Sturmbauer C. Ancient divergence in bathypelagic Lake Tanganyika deepwater cichlids: Mitochondrial phylogeny of the tribe Bathybatini. J. Mol. Evol. 60, 297–314 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter G. W. Lake Tanganyika and Its Life. Lake Tanganyika and Its Life (Oxford University Press, 1991). [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Silva M., Boeger W. A. & Pie M. R. Choice matters: Incipient speciation in Gyrodactylus corydori (Monogenoidea: Gyrodactylidae). Int. J. Parasitol. 41, 657–667 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignon M., Pariselle A. & Vanhove M. P. M. Modularity in attachment organs of African Cichlidogyrus (Platyhelminthes: Monogenea: Ancyrocephalidae) reflects phylogeny rather than host specificity or geographic distribution. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 102, 694–706 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Danley P. D. et al. The impact of the geologic history and paleoclimate on the diversification of East african cichlids. Int. J. Evol. Biol. 2012, 574851, 10.1155/2012/574851 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šimková A., Morand S., Jobet E., Gelnar M. & Verneau O. Molecular phylogeny of congeneric monogenean parasites (Dactylogyrus): a case of intrahost speciation. Evolution 58, 1001–1018 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhove M. P. M. et al. Problematic barcoding in flatworms: A case-study on monogeneans and rhabdocoels (Platyhelminthes). ZooKeys 365, 355–379 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis D. M. & Dixon N. T. Ribosomal DNA: Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetic Inference. Q. Rev. Biol. 44, 411–451 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Onsins S. E. & Rozas J. Statistical properties of new neutrality tests against population growth. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 2092–2100 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matějusová I., Gelnar M., McBeath A. J. A., Collins C. M. & Cunningham C. O. Molecular markers for gyrodactylids (Gyrodactylidae: Monogenea) from five fish families (Teleostei). Int. J. Parasitol. 31, 738–745 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C. O. Species Variation within the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) Region of Gyrodactylus (Monogenea: Gyrodactylidae) Ribosomal RNA Genes. J. Parasitol. 83, 215–219 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cable J. & Harris P. D. Gyrodactylid developmental biology: historical review, current status and future trends. Int. J. Parasitol. 32, 255–80 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevado B., Fazalova V., Backeljau T., Hanssens M. & Verheyen E. Repeated unidirectional introgression of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA between four congeneric Tanganyikan cichlids. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2253–67 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fannes W., Vanhove M. P. M., Huyse T. & Paladini G. A scanning electron microscope technique for studying the sclerites of Cichlidogyrus. Parasitol. Res. 114, 2031–4 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Konings A. Guide to Tanganyika Cichlids. (Cichlid Press, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- Maréchal C. & Poll M. In Checklist of the Freshwater Fishes of Africa (CLOFFA) (eds Daget J., Gosse J.-P., Teugels G. G. & Thys van den Audenaerde D. F. E.) 21–24, 186 (Royal Museum for Central Africa, 1991). [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann K. Relationship between host size of Anguilla anguilla and the infection level of the monogeneans Pseudodactylogyrus spp. J. Fish Biol. 35, 599–601 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Šimková A., Ondráčková M., Gelnar M. & Morand S. Morphology and coexistence of congeneric ectoparasite species: reinforcement of reproductive isolation? Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 76, 125–135 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-García M. I., Vidal-Martínez V. M. & López-Jiménez S. Monogeneans in introduced and native cichlids in México: evidence for transfer. J. Parasitol. 87, 907–9 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šimková A., Desdevise Y., Gelnar M. & Morand S. Morphometric correlates of host specificity in Dactylogyrus species (Monogenea) parasites of European Cyprinid fish. Parasitology 123, 169–77 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarkovský J., Morand S., Šimková A. & Gelnar M. Reproductive barriers between congeneric monogenean parasites (Dactylogyrus: Monogenea): Attachment apparatus morphology or copulatory organ incompatibility? Parasitol. Res. 92, 95–105 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde K. & Watson N. Morphology, microhabitats and geographical variation of Kuhnia spp. (Monogenea: Polyopisthocotylea). Int. J. Parasitol. 15, 569–586 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- Rohde K. Size differences in hamuli of Kuhnia scombri (Monogenea: Polyopisthocotylea) from different geographical areas not due to differences in host size. Int. J. Parasitol. 21, 113–4 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergens R. Variability of hard parts of opisthaptor of two species of Gyrodactylus Nordmann, 1832 (Monogenoidea) from Phoxinus phoxinus (L.). Folia Parasitol. (Praha). 23, 111–126 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergens R. & Gelnar M. Experimental verification of the effect of temperature on the size of the hard parts of haptor of Gyrodactylus katharineri Malberg 1964. Folia Parasitol. (Praha). 32, 377–380 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont M. Book review: Sublethal and chronic effects of pollutants on freshwater fish. edited by Müller R. & Lloyd R. . Regul. Rivers Res. Manag. 13, 95–96 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Kritsky D. C. & Boeger W. A. Neotropical Monogenoidea: 41. New and previously described species of Dactylogyridae (Platyhelminthes) from the gills of marine and freshwater perciform fishes (Teleostei) with proposal of a new genus and a hypothesis on phylogeny. J. Parasitol. 76, 1–21 (1990).2299514 [Google Scholar]

- Kritsky D. C. & Boeger W. A. Neotropical Monogenoidea: 41. New and previously described species of Dactylogyridae (Platyhelminthes) from the gills of marine and freshwater perciform fishes (Teleostei) with proposal of a new genus and a hypothesis on phylogeny. Zoosystema 24, 7–40 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly P. & Tavare S. The ages of alleles and a coalescent. Adv. Appl. Probab. 18, 1–19 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Ziętara M. S. & Lumme J. Speciation by host switch and adaptive radiation in a fish parasite genus Gyrodactylus (Monogenea, Gyrodactylidae). Evolution 56, 2445–58 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyse T. & Malmberg G. Molecular and morphological comparisons between Gyrodactylus ostendicus n. sp. (Monogenea: Gyrodactylidae) on Pomatoschistus microps (Krøyer) and G. harengi Malmberg, 1957 on Clupea harengus membras. Syst. Parasitol. 58, 105–13 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuusela J., Ziętara M. & Lumme J. Description of three new European cryptic species of Gyrodactylus Nordmann, 1832 supported by nuclear and mitochondrial phylogenetic characterization. Acta Parasitol. 53, 120–126 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Falush D., Stephens M. & Pritchard J. K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: dominant markers and null alleles. Mol. Ecol. Notes 7, 574–578 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinks P. Q., Thomson R. C. & Shaffer H. B. The advantages of going large: genome-wide SNPs clarify the complex population history and systematics of the threatened western pond turtle. Mol. Ecol. 23, 2228–2241 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y. X. & Li W. H. Statistical test of neutrality of mutations. Genetics 133, 693–709 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. Statistical methods to test for nucleotide mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123, 585–595 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlue M. M. et al. Seismic records of late Pleistocene aridity in Lake Tanganyika, tropical East Africa. J. Paleolimnol. 40, 635–653 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Koblmüller S., Odhiambo E. A. & Sinyinza D. Big fish, little divergence: phylogeography of Lake Tanganyika’s giant cichlid, Boulengerochromis microlepis. 748, 29–38 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genner M. J. & Turner G. F. Age of populations in the Lake Malawi cichlid radiation. Hydrobiologia 748, 121–132 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Strona G. The underrated importance of predation in transmission ecology of direct lifecycle parasites. Oikos 124, 685–690 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Ergens R. & Lom J. Causative agents of fish diseases. (Academia, 1970). [Google Scholar]

- Humason G. L. Animal tissue techniques:4th. (Freeman and Company, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- Ter Braak C. J. F. & Šmilauer P. J. CANOCO Reference Manual and User’s Guide to Canoco for Windows: Software for Canonical Ordination (Version 4). (Wageningen: Centre for Biometry, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf F. J. & Marcus L. F. A revolution morphometrics. Trends Ecol. Evol. 8, 129–32 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitteroecker P. & Gunz P. Advances in Geometric Morphometrics. Evol. Biol. 36, 235–247 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Khang T. F., Soo O. Y. M., Tan W. B. & Lim L. H. S. Monogenean anchor morphometry: systematic value, phylogenetic signal, and evolution. PeerJ 4, e1668, 10.7717/peerj.1668 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf F. Tpsdig, digitize landmarks and outlines. Version 2.10. (Stony Brook, NY: State University, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein F. L. Morphometric Tools for Landmark Data: Geometry and Biology. (Cambridge University Press, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- Nei M. Molecular evolutionary genetics. (Columbia University Press, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- Librado P. & Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451–2 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelt H. J., Forster P. & Rohl A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 37–48 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh J. W. & Bryant D. PopART: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 6, 1110–1116 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L. & Lischer H. E. L. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 564–7 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y. X. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations against population growth, hitchhiking and background selection. Genetics 147, 915–925 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. J., Rambaut A., Shapiro B. & Pybus O. G. Bayesian coalescent inference of past population dynamics from molecular sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 1185–1192 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. J., Suchard M. A., Xie D. & Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1969–73 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinilä M., Kuusela J., Ziȩtara M. S. & Lumme J. Initial steps of speciation by geographic isolation and host switch in salmonid pathogen Gyrodactylus salaris (Monogenea: Gyrodactylidae). Int. J. Parasitol. 34, 515–526 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]