Abstract

Background

Since its introduction, the sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has become the standard staging procedure in clinical node-negative melanoma patients. A negative SLNB, however, does not guarantee a recurrence-free survival. Insight into metastatic patterns and risk factors for recurrence in SLNB negative melanoma patients can provide patient tailored guidelines.

Methods

Data concerning melanoma patients who underwent SLNB between 1996 and 2015 in a single center were prospectively collected. Cox regression analyses were used to determine variables associated with overall recurrence and distant first site of recurrence in SLNB-negative patients.

Results

In 668 patients, SLNBs were performed between 1996 and 2015. Of these patients, 50.4 % were male and 49.6 % female with a median age of 55.2 (range 5.7–88.8) years. Median Breslow thickness was 2.2 (range 0.3–20) mm. The SLNB was positive in 27.8 % of patients. Recurrence rates were 53.2 % in SLNB-positive and 17.9 % in SLNB-negative patients (p < 0.001). For SLNB-negative patients, the site of first recurrence was distant in 58.5 %. Melanoma located in the head and neck region (hazard ratio 4.88, p = 0.003) and increasing Breslow thickness (hazard ratio 1.15, p = 0.013) were predictive for distant first site of recurrence in SLNB-negative patients. SLNB-negative patients with a nodular melanoma and ulceration had a recurrence rate of 43.1 %; the site of recurrence was distant in 64 % of these patients.

Conclusions

The recurrence rates of SLNB-negative nodular ulcerative melanoma patients approach those of SLNB-positive patients. Stringent follow-up is recommended in this subset of patients.

Cutaneous melanoma mainly spreads via the lymphogenic route from the sentinel lymph nodes to the adherent lymph node basin. After decades of experience, we now know that in negative sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), skip metastases are rare.1,2 Since its introduction in the early 1990s by Donald Morton, SLNB has become a widely accepted staging procedure and has become one of the most important prognostic tools in predicting outcome in cutaneous melanoma.3–7 At time of primary staging, approximately 20 % of melanoma patients are SLNB positive, with a false-negative rate less than 5 %.1,8–10

SLNB positivity is associated with several clinicopathologic characteristics, such as Breslow thickness, mitosis, and the presence of ulceration.11–13 The risk for recurrent disease is associated with this SLNB status, resulting in higher recurrence rates of up to 47 % in SLNB-positive patients and lower recurrence rates of 24 % in SLNB-negative patients.14–17 Some of these SLNB-negative patients have a distant first site of recurrence and even seem to skip the lymphogenic metastatic route.15 These patients with direct hematogenous recurrences may either have different clinicopathologic characteristics or more aggressive tumor biology.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate risk factors for recurrent disease and distant first site of recurrence in SLNB-negative melanoma patients.

Methods

The study population consisted of all consecutive melanoma patients who underwent a wide excision with a 1–2 cm margin according to the international melanoma guidelines and a SLNB at the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG) between 1996 and 2015. The SLNB technique used at the UMCG has been described elsewhere in detail.18 Patient- and tumor-related clinicopathologic characteristics were prospectively collected in a database. Data concerning patient and tumor clinicopathologic characteristics, follow-up, recurrence, and survival were retrieved from the database for analysis.

Statistics were performed by IBM SPSS 22.0 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Differences between groups were analyzes by the Chi square test for nominal variables; for continuous variables, the one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test was used. Cox regression analyses were used to determine variables associated with overall recurrence in all patients and distant first site of recurrence in SLNB-negative patients. Overall recurrence was defined as any recurrence besides recurrence in the same basin as the SLNB. On the basis of our data, the following were included in the analysis: patient demographics, histologic type, location of primary lesion, Breslow thickness, Clark level, ulceration, mitosis, regression, lymphangioinvasion, use of immunosuppressant medication, and whether the primary excision was radical. Variables were checked for correlation with Pearson’s or Spearman’s rho. Variables on a 20 % significance level in the univariate Cox regression were entered in the multivariate Cox regression analysis. In the multivariate analysis, variables were checked for multicollinearity and confounding. Confounding limit was set at 10 %. Confounders and variables with a multicollinear association were excluded from multivariate analysis. Variables with p < 0.05 in the multivariate analysis were identified as significant factors.

Melanoma-specific survival (MSS), disease-free survival (DFS), and time to death from moment of first recurrence were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier test. SLNB was defined as falsely negative if the first site of recurrence was in the same basin as the SLNB, and also when combined with systemic recurrence. To determine whether a SLNB was falsely negative in case of systemic recurrence, all positron emission tomography/computed tomography scans performed at the moment of systemic recurrence were reviewed to check for nodal involvement in the same basin as the SLNB. Because of the 100 % recurrence rate in the same basin in falsely negative SLNB patients, they were not included in the Cox regression analysis.

In the case of multisite recurrence, the recurrence site with the worst prognosis was scored as the first site of recurrence. For example, in the case of recurrence in the retroperitoneal lymph nodes and brain metastases, brain metastases were scored as the first site of recurrence. Follow-up was conducted in the UMCG. We received institutional review board approval, and the study was conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki.

Results

During the study period, a SLNB was performed in 668 patients. Baseline clinicopathologic characteristics of all patients are displayed in Table 1. Median (range) age at diagnosis of primary melanoma was 55.2 (5.7–88.8) years, and superficial spreading melanoma was the most common histologic subtype (62 %). Median overall Breslow thickness was 2.2 (0.30–20.0) mm. The median Breslow thickness in the different histologic subtypes was as follows: superficial spreading melanoma (n = 414), 1.8 (0.30–9.0) mm; nodular melanoma (n = 192), 3.4 (0.9–20) mm; acral lentiginous melanoma (n = 21), 3.6 (1.1–11) mm; other melanomas (n = 28), 3.3 (0.85–17.00) mm; and unknown histologic subtype (n = 13), 3.00 (1.0–7.0) mm. SLNB was positive in 27.8 % of patients. In SLNB-negative patients, 24 patients experienced a nodal recurrence in the same basin as the SLNB, resulting in a SLNB false-negative rate of 3.6 %. In Table 1, the differences between the baseline clinicopathologic characteristics are displayed by SLNB status. During the median follow-up of 58.8 (range 1.8–190) months, a recurrence was diagnosed in 82 of the truly SLNB-negative patients (17.9 %) and in 99 SLNB-positive patients (53.2 %).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics overall, in SLNB-negative patients, and in SLNB-positive patients (n = 668)

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 668) | SLNB negative (n = 458) | SLNB positive (n = 186) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.070 | |||

| Male | 337 (50.4) | 220 | 104 | |

| Female | 331 (49.6) | 238 | 82 | |

| Age, yearsa | 55.2 (5.7–88.8) | 55.3 (11.5–88.8) | 53.5 (5.7–88.8) | 0.890 |

| Site of primary lesion | 0.003 | |||

| Lower extremity | 228 (34.1) | 149 | 68 | |

| Head and neck | 95 (14.2) | 75 | 16 | |

| Trunk | 256 (38.3) | 166 | 86 | |

| Upper extremity | 89 (13.3) | 68 | 16 | |

| Histologic typing | 0.705 | |||

| Superficial spreading | 414 (62) | 291 | 110 | |

| Nodular | 192 (28.7) | 128 | 56 | |

| Acral lentiginous | 21 (3.1) | 12 | 7 | |

| Otherb | 28 (4.2) | 20 | 8 | |

| Breslow thickness, mm | 2.2 (0.30–20.0) | 1.9 (0.3–20.0) | 3.00 (0.8–13.0) | <0.001 |

| T stage | <0.001 | |||

| T1 (<1.00 mm) | 38 (5.7) | 7 | 0 | |

| T2 (1.01–2.00 mm) | 271 (40.6) | 155 | 34 | |

| T3 (2.01–4.00 mm) | 244 (36.5) | 114 | 83 | |

| T4 (>4.00 mm) | 114 (17.1) | 52 | 37 | |

| Clark level | 0.035 | |||

| II | 7 (1.0) | 5 | 2 | |

| III | 137 (20.5) | 109 | 26 | |

| IV | 472 (70.7) | 312 | 141 | |

| V | 40 (6.0) | 23 | 14 | |

| Ulceration | 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 223 (33.4) | 133 | 80 | |

| No | 435 (65.1) | 319 | 103 | |

| Mitosis | 0.055 | |||

| Yes | 561 (84) | 380 | 159 | |

| No | 45 (6.7) | 37 | 7 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (range)

SLNB sentinel lymph node biopsy

a Age at diagnosis of primary melanoma

b Other histologic types are verrucous, spitzoid, epithelioid, desmoplastic melanoma, and lentigo maligna melanoma

Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed the following variables to be associated with overall recurrence in SLNB-negative patients: male sex (hazard ratio [HR] 1.78, p = 0.025), increasing age (HR 1.02, p = 0.0085) per year, melanoma located in the head and neck region (HR 2.16, p = 0.024), nodular melanoma (HR 1.82, p = 0.028), and presence of ulceration (HR 2.11, p = 0.002). In SLNB-positive patients, excisional biopsy decreased the risk for recurrence (HR 0.49, p = 0.005) as well as melanoma located on the upper extremity (HR 0.37, p = 0.045). Male sex (HR 1.10, p = 0.048), increasing Breslow thickness (HR 1.09, p = 0.048), and the presence of ulceration (HR 2.15, p < 0.001) were associated with recurrence in this group. Mitosis and Clark level were not included in both multivariate analyses because of multicollinearity with Breslow thickness (Table 2). In SLNB-negative patients with a nodular melanoma, the recurrence rate was 38 (29.7 %) of 128; if ulceration was also present in the primary melanoma, the recurrence rate was increased to 43.1 %. The site of recurrence was distant in 64 % of these patients. Of all SLNB-negative patients, 12.7 % had nodular ulcerated melanoma. In the entire group of SLNB-negative patients with nodular melanoma, 25 % eventually progressed to distant disease, 34.5 % if ulceration was also present.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of clinicopathologic characteristics associated with overall recurrence in all patients and by SLNB status (n = 668)

| Characteristic | Recurrence overall (n = 205) | Univariate SLNB (n = 82) | Multivariate SLNB negative | Univariate SLNB positive (n = 99) | Multivariate SLNB positive | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | p | HR | p | 95 % CI | HR | p | HR | p | 95 % CI | ||

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 126 (61.5) | 2.34 | <0.001* | 1.78 | 0.025 | 1.08–2.94 | 1.34 | 0.156* | 1.10 | 0.048* | 1.01–1.20 |

| Female | 79 (38.5) | ||||||||||

| Agea | 58.66 (19.2–81.4) | 1.03 | 0.001* | 1.02 | 0.008* | 1.01–1.04 | 1.02 | 0.036* | 1.01 | 0.127 | 0.99–1.03 |

| Site of primary lesion | |||||||||||

| Lower extremity | 71 (34.6) | 1.00 | 0.010* | 1.00 | 0.006* | 1.00 | 0.100 | 1.00 | 0.035* | ||

| Head/neck | 34 (16.6) | 2.20 | 0.011* | 2.16 | 0.024* | 1.11–4.21 | 1.48 | 0.264 | 1.79 | 0.144 | 0.82–3.92 |

| Trunk | 84 (41) | 1.47 | 0.156 | 1.34 | 0.346 | 0.73–2.64 | 0.93 | 0.600 | 0.89 | 0.687 | 0.53–1.52 |

| Upper extremity | 16 (7.8) | 0.56 | 0.206 | 0.43 | 0.068 | 0.17–1.07 | 0.39 | 0.046* | 0.37 | 0.045* | 0.14–0.98 |

| Histologic typing | |||||||||||

| Superficial spreading | 106 (51.7) | 1.00 | 0.002* | 1.00 | 0.164 | 1.00 | 0.840 | ||||

| Nodular | 74 (36.1) | 2.50 | <0.001* | 1.82 | 0.028* | 1.07–3.09 | 0.91 | 0.669 | |||

| Acral lentiginous | 11 (5.4) | 3.45 | 0.019 | 2.76 | 0.080 | 0.89–8.59 | 1.46 | 0.418 | |||

| Otherb | 10 (4.9) | 1.82 | 0.257 | 1.02 | 0.978 | 0.30–3.50 | 1.31 | 0.534 | |||

| Excision radical | |||||||||||

| Yes | 153 (74.6) | 0.93 | 0.786 | 0.49 | 0.001* | 0.49 | 0.005* | 0.30–0.81 | |||

| No | 52 (25.4) | ||||||||||

| Breslow thickness, mm | 3.00 (1.05–20.00) | 1.16 | <0.001* | 1.06 | 0.151 | 0.98–1.16 | 1.11 | 0.007* | 1.09 | 0.048* | 1.00–1.20 |

| Clark level | |||||||||||

| II | 1 (0.5) | 1.91 | 0.524 | ||||||||

| III | 27 (13.2) | 0.79 | 0.443 | 0.60 | 0.133 | ||||||

| IV | 150 (73.2) | 1.00 | 0.042* | 1.00 | 0.311 | ||||||

| V | 23 (11.2) | 2.39 | 0.012* | 1.39 | 0.333 | ||||||

| Ulceration | |||||||||||

| Yes | 110 (53.7) | 3.02 | <0.001* | 2.11 | 0.002* | 1.31–3.39 | 2.28 | <0.001* | 2.15 | <0.001* | 1.40–3.29 |

| No | 92 (44.9) | ||||||||||

| Mitosis | |||||||||||

| Yes | 178 (86.8) | 5.58 | 0.088 | 2.32 | 0.240 | ||||||

| No | 4 (2.0) | ||||||||||

| Regression | |||||||||||

| Yes | 22 (10.7) | 0.99 | 0.840 | 0.97 | 0.206 | ||||||

| No | 111 (54.1) | ||||||||||

| Lymphangioinvasion | |||||||||||

| Yes | 18 (8.8) | 1.14 | 0.081 | 1.16 | 0.172 | 0.94–1.43 | 0.92 | 0.641 | |||

| No | 184 (89.8) | ||||||||||

| Immunosuppressant medication | |||||||||||

| Yes | 7 (3.4) | 2.37 | 0.143 | 1.12 | 0.819 | 1.97 | 0.193 | 0.71–5.43 | |||

| No | 198 (96.6) | ||||||||||

Data are presented as n (%) or median (range)

SLNB sentinel lymph node biopsy, NA not applicable

* p < 0.05. All variables with significance level of p < 0.2 in univariate Cox regression analysis were entered into multivariate Cox regression analysis

a Age at diagnosis of primary melanoma

b Other histologic types are verrucous, spitzoid, epithelioid, desmoplastic melanoma, and lentigo maligna melanoma

Table 3 shows the distribution of recurrence patterns for both SLNB-negative and -positive patients. The most common site of first recurrence was distant in all SLNB categories. In SLNB-negative patients, this was 58.5 % of all first recurrence sites. Of all 181 patients with recurrence, 77 % developed overall distant disease at some point in the course of their disease. If patients progressed to stage IV disease during the course of their disease, the largest portion of these distant recurrences was American Joint Committee on Cancer stage M1c (82.5 %).

Table 3.

Recurrence rates and site of first recurrence in SLNB-negative and -positive patients

| Characteristic | Overall, n (%) | SLNB negative, n | SLNB positive, n | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrence | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 205 (30.7) | 82 | 99 | |

| No | 463 (69.3) | 376 | 87 | |

| Type of first recurrence | 0.053 | |||

| Locoregional | 30 (14.7) | 14 | 16 | |

| In transit | 43 (21.1) | 18 | 25 | |

| Basin of SLNB/CLND | 30 (14.7) | 0 | 9 | |

| Lymphatic | 3 (1.5) | 1 | 2 | |

| Distant | 98 (48) | 49 | 46 | |

| M-stage distant recurrence | 0.278 | |||

| M1a | 4 (4.1) | 3 | 1 | |

| M1b | 12 (12.4) | 4 | 8 | |

| M1c | 80 (82.5) | 42 | 37 | |

| Unknown | 1 |

SLNB sentinel lymph node biopsy, CLND completion lymph node dissection

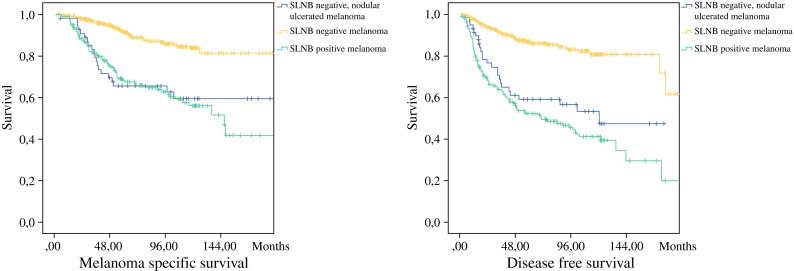

MSS and DFS was significantly worse for SLNB-positive patients compared to SLNB-negative patients (p < 0.001). If a recurrence had occurred, survival did not differ between SLNB-negative and SLNB-positive patients. There was a significant difference between MSS and DFS in SLNB-negative patients with ulcerated and nodular melanoma compared to the overall SLNB-negative group (p < 0.001; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Survival split by sentinel lymph node biopsy negativity or positivity with nodular subtype and ulceration. a Melanoma-specific survival. b Disease-free survival

Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed melanomas located on the head and neck (HR 4.88, p = 0.003), trunk (HR 3.33, p = 0.012), and upper extremity (HR 6.60, p = 0.008) to be associated with distant first site of recurrence in SLNB-negative melanoma patients as well as increasing Breslow thickness (HR 1.15, p = 0.013). The absence of mitosis (HR 0.06, p = 0.035) is protective for distant first site of recurrence in SLNB-negative patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of clinicopathologic characteristics associated with distant first site of recurrence in SLNB-negative patients

| Characteristic | Distant first recurrence (n = 48) | Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | p | HR | p | 95 % CI | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 32 (66.7) | 1.43 | 0.243 | |||

| Female | 16 (33.3) | |||||

| Age, ya | 60.2 (19.4–79.6) | 1.03 | 0.009* | 1.02 | 0.160 | 0.99–1.04 |

| Site of primary lesion | ||||||

| Lower extremity | 11 (22.9 %) | 1.00 | 0.113 | 1.00 | 0.011* | |

| Head/neck | 13 (27.1) | 2.79 | 0.015* | 4.88 | 0.003* | 1.74–13.73 |

| Trunk | 20 (41.7) | 1.68 | 0.169 | 3.33 | 0.012* | 1.31–8.48 |

| Upper extremity | 4 (8.3) | 1.68 | 0.374 | 6.60 | 0.008* | 1.63–26.74 |

| Histologic typing | ||||||

| Superficial spreading | 19 (39.6) | 1.00 | 0.124 | 1.00 | 0.103 | |

| Nodular | 24 (50) | 2.06 | 0.022* | 1.91 | 0.079 | 0.93–3.93 |

| Acral lentiginous | 2 (4.2) | 2.32 | 0.266 | 2.05 | 0.437 | 0.34–12.54 |

| Otherb | 3 (6.3) | 1.18 | 0.795 | 0.13 | 0.107 | 0.01–1.56 |

| Breslow thickness, mm | 3.00 (1.05–20.0) | 1.12 | 0.008* | 1.15 | 0.013* | 1.03–1.29 |

| Clark level | ||||||

| II | 0 | |||||

| III | 9 (18.8) | 1.59 | 0.650 | |||

| IV | 29 (60.4) | 1.00 | 0.581 | |||

| V | 7 (14.6) | 0.77 | 0.548 | |||

| Missing | 3 (6.2) | |||||

| Ulceration | ||||||

| Yes | 27 (41.7) | 1.42 | 0.231 | |||

| No | 20 (56.3) | |||||

| Missing | 1 (2.1) | |||||

| Mitosis | ||||||

| Yes | 42 (87.5) | |||||

| No | 1 (2.1) | 0.03 | 0.004* | 0.06 | 0.035* | 0.01–0.82 |

| Missing | 5 (10.4) | |||||

| Regression | ||||||

| Yes | 21 (43.8) | 0.99 | 0.777 | |||

| No | 7 (14.6) | |||||

| Unknown | 20 (41.7) | |||||

| Lymphangioinvasion | ||||||

| Yes | 4 (8.3) | 1.03 | 0.766 | 1.04 | 0.880 | 0.63–1.71 |

| No | 43 (89.6) | |||||

| Immunosuppressant medication | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (2.1) | |||||

| No | 47 (97.9) | 0.82 | 0.843 | |||

Data are presented as n (%) or median (range)

SLNB sentinel lymph node biopsy

* p < 0.05. All variables with significance level of p < 0.2 in univariate Cox regression analysis were entered into multivariate Cox regression analysis

a Age at diagnosis of primary melanoma

b Other histologic types are verrucous, spitzoid, epithelioid, desmoplastic melanoma, and lentigo maligna melanoma

Discussion

The current study revealed that in SLNB-negative patients, recurrence rates approach the recurrence rates of SLNB-positive patients (43.1 vs. 53.2 %) if the unfavorable variables nodular histologic subtype and ulceration are accounted for. These pathologic characteristics are present in 12.7 % of SLNB-negative melanoma patients. As displayed by the Kaplan–Meier curves in Fig. 1, DFS and MSS is significantly worse for SLNB-negative nodular and ulcerated melanoma patients compared to the overall SLNB-negative group.

Risk factors for recurrent disease in SLNB-negative patients were increasing age, male sex, melanoma located on the head and neck region, nodular melanoma, and presence of ulceration (Table 2). Except for nodular melanoma, the significance of these variables in predicting recurrent disease in SLNB-negative melanoma patients was previously illustrated by several authors.17,19,20 O’Connell et al. recently stated that nodular histologic subtype approached significance in predicting recurrence in SLNB negative melanoma patients.17 Obviously a negative SLNB might create the impression of a less aggressive melanoma; however, one cannot be so sure when it concerns a nodular subtype. Because the recurrence percentage of SLNB-negative patients with ulcerated nodular melanoma approaches the recurrence percentage of SLNB-positive melanoma patients, primary tumor characteristics are apparently more relevant for recurrence in these patients than the status of the sentinel node. In absence of a lymphogenous recurrence and/or positive SLNB, risk factors for distant first site of recurrence were melanoma located on the head and neck, increasing Breslow thickness, and the presence of ulceration. In SLNB-negative patients, distant first site of recurrence occurred in 58.8 % of all recurrences. In this subset of patients, the melanoma seems to skip the lymphogenic metastatic route and metastasizes directly hematogenously. Overall, it is expected that unfavorable tumor clinicopathologic characteristics should be more frequent in the SLNB-positive group.6,12,13,21 Previous publications on SLNB-negative patients revealed increasing Breslow thickness, ulceration, head and neck melanoma, and unexpected lymph drainage patterns to be predictors for distant recurrence.14–16,19,20 Unexpected or aberrant lymph drainage patterns are expected in head and neck melanomas more than melanomas located on the upper and lower extremity. An affinity for hematogenous spread is suggested in this subset of melanomas.22,23 This might be an explanation for our findings.

The recurrence percentages were increased by more than twofold in the group of SLNB-negative patients with a nodular ulcerated melanoma compared to the whole group, suggesting a higher likeliness of hematogenous spread in these patients. Morton et al. posed two dissemination theories: the incubator hypothesis and the marker hypothesis. According to the first hypothesis, melanoma metastasizes mostly to the lymph nodes and in approximately 10 % directly via the hematogenous route. Tumor cells may grow in the SLNB but might incubate before spreading to distant sites. Removal of the SLNB and adherent lymph nodes can prevent further spread. The marker hypothesis, however, implicates a simultaneous spread. Tumor load in the SLNB is merely a marker for the ability of the tumor to spread. According to both hypotheses, the absence of melanoma cells in the SLNB indicates a primary melanoma unlikely to disseminate to distant sites.24 Perhaps the 10 % direct distant spread posed in the incubator hypothesis is caused by melanomas with unfavorable prognostics such as nodular subtype and ulceration. This hematogenous dissemination route was also described by Gershenwald et al., who suggested a subset of patients with a pure hematogenous dissemination route, without nodal involvement.16 Nodular melanoma is usually detected at a higher Breslow thickness than superficial spreading melanoma, even though the duration of change in a lesion before treatment is shorter in nodular melanoma than the superficial spreading type, which is suggestive for aggressive biologic behavior.25 Lin et al. published results where a significantly lower amount of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were found in nodular melanoma compared to superficial spreading melanoma, suggesting a different immunogenicity between the different histologic subtypes.26 Unfortunately, we do not routinely look for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in our institution, so we were not able to cross-reference this to our data.

The presented data on increased recurrence rates in patients with ulcerated nodular melanoma, increasing Breslow thickness melanoma, and head and neck localization are crucial for clinicians involved in melanoma care, as these findings can not only alter decisions on the duration and frequency of follow-up but also increase the awareness of the likelihood of distant recurrence in these patients. Therefore, we propose to distinguish a high risk for recurrence in the SLNB-negative subgroup.

SLNB-positive patients have a worse DFS compared to SLNB-negative patients. However, when a recurrence occurs, survival is similar. Survival was shorter in patients with a distant first site of recurrence compared to other recurrent sites, which has been extensively described in the literature.15,27

Patients with unfavorable primary clinicopathologic characteristics such as positive SLNB are already considered for adjuvant targeted therapy or immunotherapy trials. It might also be worth considering high-risk SLNB-negative patients for inclusion. First, however, adjuvant studies have yet to show a beneficial effect in SLNB-positive patients with respect to MSS. Before expanding inclusion criteria, the risk–benefit ratio should be properly assessed.

Although many researchers have focused on recurrence patterns of melanoma, we are still unable to accurately predict the course of the disease in many patients. We believe that most of the biological behavior in the end can be explained by possible unrevealed genetic mutations with distinctive biological behavior. Today, melanoma is characterized and staged by clinicopathologic features. There might be a role for genetic profiling aiming to identify melanoma patients with a misleadingly favorable SLNB pathologic prognosis whose disease is likely to recur in the future.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JH, et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg. 1992;127:392–399. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420040034005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reintgen D, Cruse CW, Wells K, et al. The orderly progression of melanoma nodal metastases. Ann Surg. 1994;220:759–767. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199412000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton DL, Cochran AJ, Thompson JF, et al. Sentinel node biopsy for early-stage melanoma: accuracy and morbidity in MSLT-I, an international multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2005;242:302–311. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000181092.50141.fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1307–1317. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199–6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong SL, Balch CM, Hurley P, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology joint clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2912–2918. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elsaesser O, Leiter U, Buettner PG, et al. Prognosis of sentinel node staged patients with primary cutaneous melanoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faries MB, Thompson JF, Cochran A, et al. The impact on morbidity and length of stay of early versus delayed complete lymphadenectomy in melanoma: results of the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (I) Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3324–3329. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:599–609. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niebling MG, Pleijhuis RG, Bastiaannet E, Brouwers AH, van Dam GM, Hoekstra HJ. A systematic review and meta-analyses of sentinel lymph node identification in breast cancer and melanoma, a plea for tracer mapping. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Speijers MJ, Bastiaannet E, Sloot S, Suurmeijer AJ, Hoekstra HJ. Tumor mitotic rate added to the equation: melanoma prognostic factors changed? A single-institution database study on the prognostic value of tumor mitotic rate for sentinel lymph node status and survival of cutaneous melanoma patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2978–2987. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4349-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han D, Zager JS, Shyr Y, et al. Clinicopathologic predictors of sentinel lymph node metastasis in thin melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4387–4393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rughani MG, Swan MC, Adams TS, et al. Sentinel node status predicts survival in thick melanomas: the Oxford perspective. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:936–942. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yee VS, Thompson JF, McKinnon JG, et al. Outcome in 846 cutaneous melanoma patients from a single center after a negative sentinel node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:429–439. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalal KM, Patel A, Brady MS, Jaques DP, Coit DG. Patterns of first-recurrence and post-recurrence survival in patients with primary cutaneous melanoma after sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1934–1942. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9357-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gershenwald JE, Colome MI, Lee JE, et al. Patterns of recurrence following a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy in 243 patients with stage I or II melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2253–2260. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.6.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connell EP, O’Leary DP, Fogarty K, Khan ZJ, Redmond HP. Predictors and patterns of melanoma recurrence following a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. Melanoma Res. 2016;26:66–70. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doting MH, Hoekstra HJ, Plukker JT, et al. Is sentinel node biopsy beneficial in melanoma patients? A report on 200 patients with cutaneous melanoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:673–678. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2002.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaveh AH, Seminara NM, Barnes MA, et al. Aberrant lymphatic drainage and risk for melanoma recurrence after negative sentinel node biopsy in middle-aged and older men. Head Neck. 2016;38:754–760. doi: 10.1002/hed.24094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones EL, Jones TS, Pearlman NW, et al. Long-term follow-up and survival of patients following a recurrence of melanoma after a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy result. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:456–461. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mozzillo N, Pennacchioli E, Gandini S, et al. Sentinel node biopsy in thin and thick melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2780–2786. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2826-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daryanani D, Plukker JT, de Jong MA, et al. Increased incidence of brain metastases in cutaneous head and neck melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2005;15:119–124. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200504000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huismans AM, Haydu LE, Shannon KF, et al. Primary melanoma location on the scalp is an important risk factor for brain metastasis: a study of 1687 patients with cutaneous head and neck melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3985–3991. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3829-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton DL, Hoon DS, Cochran AJ, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for early-stage melanoma: therapeutic utility and implications of nodal microanatomy and molecular staging for improving the accuracy of detection of nodal micrometastases. Ann Surg. 2003;238:538–549. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000086543.45557.cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenwald HS, Friedman EB, Osman I. Superficial spreading and nodular melanoma are distinct biological entities: a challenge to the linear progression model. Melanoma Res. 2012;22:1–8. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32834e6aa0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin RL, Wang TJ, Joyce CJ, et al. Decreased tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in nodular melanomas compared with matched superficial spreading melanomas. Melanoma Res. 2016;26:524–527. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zogakis TG, Essner R, Wang HJ, et al. Melanoma recurrence patterns after negative sentinel lymphadenectomy. Arch Surg. 2005;140:865–871. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.9.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]