Abstract

Activating FGFR3 mutations in human result in achondroplasia (ACH), the most frequent form of dwarfism, where cartilages are severely disturbed causing long bones, cranial base and vertebrae defects. Because mandibular development and growth rely on cartilages that guide or directly participate to the ossification process, we investigated the impact of FGFR3 mutations on mandibular shape, size and position. By using CT scan imaging of ACH children and by analyzing Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice, a model of ACH, we show that FGFR3 gain-of-function mutations lead to structural anomalies of primary (Meckel’s) and secondary (condylar) cartilages of the mandible, resulting in mandibular hypoplasia and dysmorphogenesis. These defects are likely related to a defective chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation and pan-FGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor NVP-BGJ398 corrects Meckel’s and condylar cartilages defects ex vivo. Moreover, we show that low dose of NVP-BGJ398 improves in vivo condyle growth and corrects dysmorphologies in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice, suggesting that postnatal treatment with NVP-BGJ398 mice might offer a new therapeutic strategy to improve mandible anomalies in ACH and others FGFR3-related disorders.

Introduction

Achondroplasia (ACH) is the most common form of chondrodysplasia and is characterized by a rhizomelic dwarfism with short limbs, macrocephaly, frontal bossing and midface hypoplasia (1–3). ACH is caused by an activating mutation of Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 3 (FGFR3) that affects both endochondral and membranous ossification (3–5). FGFR3 over-activation disturbs the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes in the growth plate of long bones (6–8) and synchondroses of the cranial base (3,9). Other cartilaginous structures are affected in ACH, such as the inner ear (10), vertebral bodies and intervertebral disc (11) and joints (7).

Mandibular growth relies greatly on primary and secondary cartilages, even though their exact roles in the acquisition of the mandible final shape and size are not fully understood (12,13). Meckel’s cartilage (MC) is a rod-shaped primary cartilage that runs through the mandibular process of the first pharyngeal arch and acts as a morphogenic template for the membranous ossification of the mandible body. It is transiently present in the developing mandible and disappears at birth. Secondary cartilages (symphyseal, angular and condylar cartilages) form prenatally and eventually ossify by endochondral ossification during post-natal growth, serving as growth centers (12). The central role of cartilages in mandibular development and growth is exemplified by the mandibular phenotype observed in several chondrodysplasias where mutations in genes involved in chondrocyte function, such as Collagen II (responsible for Achondrogenesis type II), Sox9 (Campomelic dysplasia) or PTHrP (Jansen type of metaphyseal chondrodysplasia) result in abnormal mandibular shape, size or position (14–16).

Mutations of FGFR1, FGFR2 and FGFR3 genes are associated with various aspects of abnormal craniofacial development such as craniosynostoses and maxillary hypoplasia (2,17,18). FGFR2 and FGFR3 are expressed in MC (19,20) and throughout all phases of the chick mandibular development (21). FGFR3 signaling is required for the elongation of chick MC and FGFR2 and FGFR3 play a role during membranous ossification of mandible (22). Mandibular defects have also been observed in Fgfr1/2dckomice, with a shorter and smaller mandible at birth (20). The deletion in mice of the FGFR3 signaling molecule Snail (23) is associated with a growth retardation of MC and a reduction in mandibular length (24) and mice deficient for the FGFR3 ligand FGF18 display a reduced size of MC and a hypoplastic mandible (25). These data support the role of FGFR signaling in the elongation of MC and morphogenesis of the mandible.

However, it is unknown whether mandibular growth and development are affected in children with ACH and whether mandibular cartilages are disturbed by FGFR3 mutations. Analysis of lateral cephalogram from adult ACH patients has shown a prognathic mandible (i.e. anteriorly displaced) (26,27). It has also been reported that in humans, other skeletal dysplasia caused by activating mutations of FGFR3 can result in mandibular dysmorphogenesis as seen in thanatophoric dysplasia (TD) (28), and Muenke syndrome (MS) (29).

In this article, we studied the mandible growth and development in children with ACH and observed an abnormal shape, size and position of the mandible. We compared the human data with those obtained with a mouse model of ACH (Fgfr3Y367C/+) (10), for which we analyzed MC and secondary cartilages of the mandible. We observed proliferation and differentiation defects in chondrocytes of the mandibular cartilages and a delay in the replacement of MC by bone. By targeting the excessive activity of FGFR3 with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor NVP-BGJ398 (30), in organ cultures, we corrected the modifications of size and shape of the mandibles. Using NVP-BGJ398 in vivo, we observed a strong improvement of the mandibular phenotype. Taken together, these data bring out anomalies of the mandible in ACH and its mouse model and offer new perspective of treatment for ACH.

Results

Achondroplasia results in mandibular hypoplasia and dysmorphogenesis

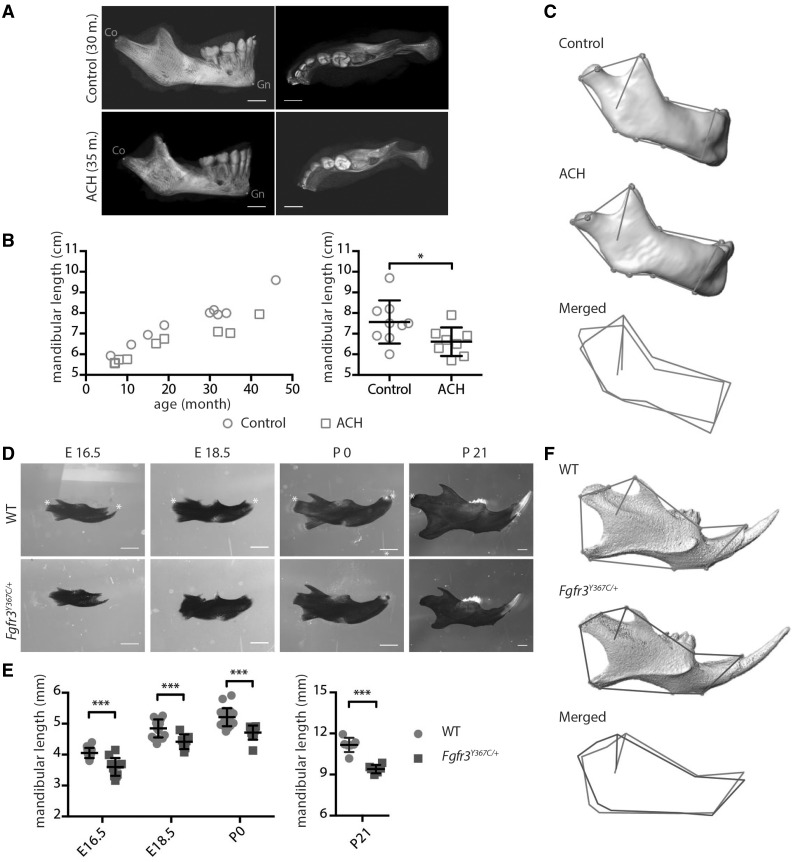

Although the craniofacial phenotype of patients with ACH has been described (2,3,26), no specific analysis of the mandible has been conducted. We took advantage of CT images acquired for assessment of risks for cervicomedullary-junction compression in infants with ACH (n = 8, mean age: 21.3 months) and compared these images with those of age-matched controls obtained after traumatic events (n = 9, mean age: 24.9 months). The length of the mandible, measured as the distance between condylion (Co) and gnathion (Gn), was significantly and consistently decreased in ACH patients compared to controls (−14%; P < 0.05; Fig. 1A and B). Mandibular body length [Gonion (Go) – Menton (Me)] and mandibular ramus length (Go – Co) were also significantly decreased in ACH children (−16%; P < 0.01 and −17%; P < 0.05, respectively).

Figure 1.

FGFR3 over activation in humans and mice results in mandibular hypoplasia and dysmorphogenesis. (A) 3D reconstructed CT images with volume rendering of a control and ACH patient (scale bar = 1 cm). (B) Mandible length, measured as the distance between condylion (Co) and gnathion (Gn) on sagittal sections of 3D reconstructed CT images of controls (n = 9, mean age: 24.9 months) or ACH patients (n = 8, mean age: 21.3 months) and plotted against the age of the children. (C) Landmarks and associated wireframes measured on the 3D reconstructed human mandibles and corresponding superimposition of the control and ACH wireframes computed on the basis of PC scores along PC1, the PC best separating the two groups and accounting for 47% of total shape variance. (D and E) Mandible length of embryos (E16.5 and E18.5), new born and 3-week-old WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice (n ≥ 6 individuals for each age and genotype), measured following alcian blue and alizarin red staining between the condylar and symphyseal ends (marked with *) (scale bar = 1 mm). (F) Landmarks and associated wireframes measured on the 3D reconstructed mouse mandibles and corresponding superimposition of the control and Fgfr3Y367C/+ wireframes computed on the basis of PC scores along PC1, the PC best separating the two groups and accounting for 78% of total shape variance. Data shown as mean with SD; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005.

The analysis of tridimensional coordinates of anatomical landmarks with geometric morphometrics (31) showed differences in mandible shape between ACH patients and controls. Principal components analysis (PCA) of the human mandible shape resulted in the separation of ACH patients and controls along PC1 accounting for 47% of total variance on the basis of shape features represented in Figure 1C. When compared with controls, mandibles of ACH children were characterized by a defective orientation and size of the ramus with prominent coronoid processes and relatively shorter condyles.

FGFR3 activation in mice results in mandibular hypoplasia and dysmorphogenesis

The role of Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 during mandibular development was demonstrated in mice with a mesenchyme-specific disruption of Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 (20), while the impact of an activating Fgfr3 mutation on the mandible has not been studied. Here, we compared the mandible size and shape of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice that accurately mimic ACH (3,10,32) with wild-type (WT) mice at different ages. We sacrificed pregnant mice to collect Fgfr3Y367C/+ and control littermate embryos at gestational day E16.5 and E18.5. Mice were also sacrificed at postnatal day 0 and 21. The mandibles were dissected and stained with alcian blue for cartilage and alizarin red for mineralized tissue. We observed a significant reduction in the length of the mandible body in the mutant mice at all time-points: −11% P < 0.005, −9% P < 0.005, −10% P < 0.005, −16% P < 0.0001 compared with WT littermates at E16.5, E18.5, P0 and P21, respectively (Fig. 1D and E).

To identify potential dysmorphologies in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mandibles in addition to the hypoplasia, we measured anatomical landmarks on three-dimensional (3D) reconstructed micro-CT images of P21 mandibles and analyzed their coordinates with geometric morphometrics. The PCA of the mandible shape resulted in the separation of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice and controls littermates along PC1 accounting for 78% of total variance on the basis of shape features (mainly located on the ramus) represented in Fig. 1F. Our results revealed that the shape changes observed in ACH patients, and Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice were relatively similar.

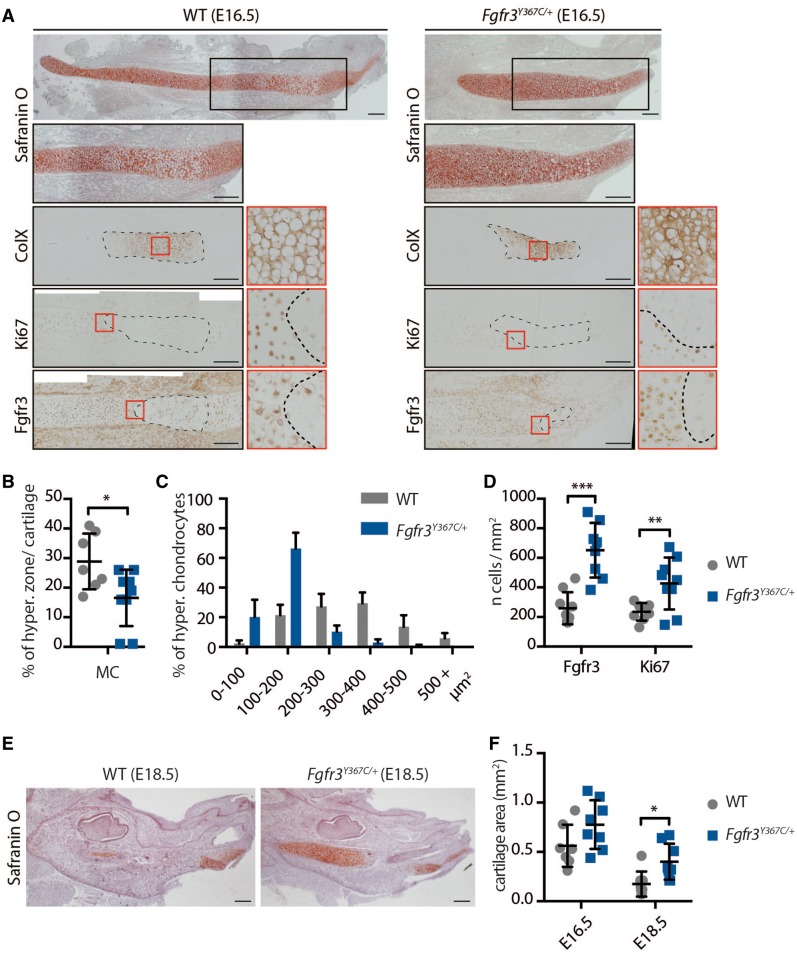

Chondrocytes homeostasis is disturbed in MC of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice

We hypothesized that Fgfr3 activation disturbs chondrocytes homeostasis in MC, as it was shown in other cartilages, such as the growth plate (10), the inner ear (10), the cranial base synchondroses (3) or vertebral bodies (11), and that these defects could be responsible for the mandibular hypoplasia and dysmorphogenesis observed in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice. We therefore collected embryos at gestational day E16.5 and E18.5 and analyzed markers of chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation on histological sections.

At E16.5, MC was readily identifiable on sections stained with safranin’O (Fig. 2A). We focused on the cartilage within the developing mandible. In its central part, chondrocytes are organized into layers (33,34), as in a growth plate or a synchondrosis. We used several markers to compare the spatial organization of the chondrocytes into distinct zones in WT and mutant embryos and observed that the chondrocyte differentiation was disrupted in mutant embryos. First, immunostaining for Collagen X showed that the size of the hypertrophic chondrocytes zone relative to the total size of the cartilage was reduced (−43% compared to WT, P < 0.05; Fig. 2A and B), as was the size of individual hypertrophic chondrocytes (−51% compared to WT, P < 0.0001; Fig. 2A and C) in Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos. Immunostaining of the proliferation marker Ki67 indicated that more cells were proliferating in MC of mutant embryos (+81% compared to WT, P < 0.01; Fig. 2A and D). In WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos, the zones of proliferating and hypertrophic cells were clearly delimited and were almost completely mutually exclusive (Fig. 2A). We then observed that the number of Fgfr3-positive cells in this cartilage was increased in Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos (+151%, P < 0.0001; Fig. 2A and D) as reported in the growth plate of the same mouse model (11,35) and ACH and TD fetuses (6). FGFR3 exhibits a specific pattern of expression during chondrocyte differentiation (5,36), and in the growth plate, its expression is mostly limited to the resting, proliferating and pre-hypertrophic chondrocytes (37). In WT embryos, Fgfr3 was expressed by proliferative and prehypertrophic chondrocytes (Fig. 2A), whereas in Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos, the pattern of expression was less clearly delimited, with an overlapping of Collagen X and Fgfr3-positive cartilage areas.

Figure 2.

Chondrocytes homeostasis is disturbed in Meckel’s cartilage of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice. (A) Histological staining (Safranin’O) and immunostaining for Collagen X, Ki67 (proliferation marker) and Fgfr3 of MC of WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ E16.5 embryos. An enlargement of the ColX immunostaining (red box) highlights the modification in the size of hypertrophic chondrocytes in Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos (scale bar = 200 μm). Area delimited with doted lines on the ColX panel corresponds to the hyperthrophic zone. Areas delimited with doted lines on the Ki67 and Fgfr3 panels correspond to immunonegative zones (respectively non-proliferative and Fgfr3-negative). Enlargements of the Ki67 and Fgfr3 immunostainings (red box) highlight the limits of the positive and negative zones. (B) Measurement of the ColX positive zone inside MC of WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ E16.5 embryos (n ≥ 7 individuals for each genotype). (C) Mean percentage of hypertrophic chondrocytes for different size categories (expressed in μm2) inside MC of WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ E16.5 embryos (n ≥ 50 cells from n ≥ 6 individuals for each genotype). (D) Mean number of immuno-positive cells for Fgfr3 or Ki67 inside MC of WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ E16.5 embryos (n ≥ 7 individuals for each genotype). (E) Histological staining (Safranin’O) of WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ E18.5 embryos (scale bar = 200 μm). (F) Mean cartilage area, measured on sagittal sections of MC in WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ E16.5 and E18.5 embryos (n ≥ 7 individuals for each age and genotype). Data shown as mean with SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005.

Differentiation into hypertrophic chondrocytes precedes and contributes to the disappearance of MC and replacement by bone (38,39). At E18.5, large remnants of cartilage were detected in Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos, in contrast with WT embryos where MC was mostly replaced by bone (Fig. 2E and F) and the size of MC was significantly increased in Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos mandible (+129%, P < 0.05). Similar defects lead to an ossification delay in the growth plate (40).

Overall, these results suggest that Fgfr3 constitutive activation disturbed the chondrocytes proliferation and differentiation and delayed the ossification process in MC.

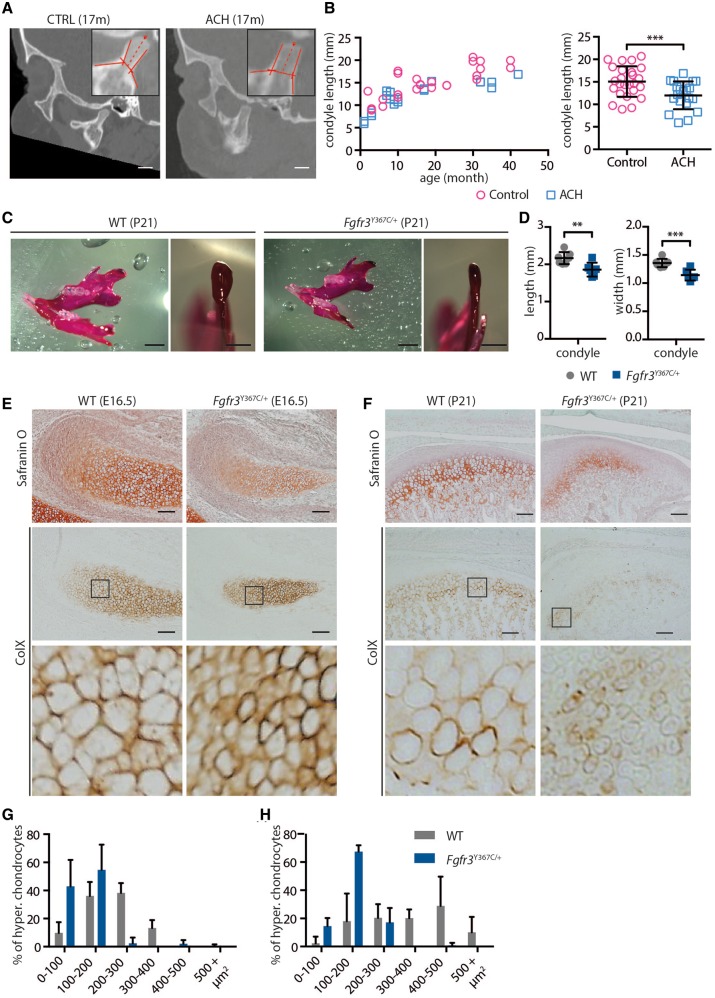

FGFR3 activation reduces condylar growth in humans and mice

Deviations in the growth of the mandibular condyle can have major functional and aesthetic consequences (41). Although the majority of the mandible is formed by membranous ossification, the upper part of the ramus is formed by endochondral ossification of the condylar cartilage. This process allows the mandible to elongate and grow upward and backward (42). In both humans and mice, endochondral ossification is severely disturbed by FGFR3 activating mutations and defects in condylar cartilage could contribute to mandibular hypoplasia and dysmorphogenesis. For these reasons, we characterized the condylar process, first in children with ACH, then in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice. We observed on sagittal sections from CT images that the length of the condylar neck in children with ACH was reduced compared to age-matched controls (−21%, P < 0.005; ACH: n = 12, mean age= 32.4 months; controls: n = 14, mean age = 32.4 months) (Fig. 3A and B). This reduction was observed in children aged from 1 to 42 months. In Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice (P21), condylar hypoplasia was also present (Fig. 3C and D). In mutant mice, condyles were significantly reduced in length (−14.2%, P < 0.01) and width (−15.8%, P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

FGFR3 over-activation in humans and mice results in condyle hypoplasia. (A) Representative sagittal sections of a control and ACH child, both 17 months of age, generated from the CT scans (scale bar = 1 cm). (B) Condylar neck length, measured on CT scans sagittal sections of controls (n = 14, mean age = 32.4 months) or ACH patients (n = 12, mean age = 32.4 months) and plotted against the age of the children. (C) Representative macroscopic views of condyles of 3-week-old WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice, following alcian blue and alizarin red staining (scale bars = 2 and 1 mm). (D) Condylar neck length of 3-week-old WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice, measured following alcian blue and alizarin red staining (n ≥ 6 individuals for each genotype). (E and F) Histological staining (Safranin’O) and immunostaining for Collagen X of the condylar cartilage of WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ E16.5 embryos (E) and 3-week-old mice (F) (scale bar = 100 μm). An enlargement of the ColX immunostaining (black box) highlights the modification in the size of hypertrophic chondrocytes in Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos and P21 mice. (G and H) Mean percentage of hypertrophic chondrocytes for different size categories (expressed in μm2) inside the condylar cartilage of WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ E16.5 embryos (G) and 3 weeks old mice (H) (n ≥ 50 cells from n ≥ 6 individuals for each age and genotype). Data shown as mean with SD; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005.

To identify the mechanism that led to this shorter condylar neck, we examined the condylar cartilage on histological sections of E16.5 embryos and P21 mice. In Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice, the size of the hypertrophic zone in the cartilage was reduced compared to WT littermates as was the average size of individual hypertrophic chondrocytes (E16.5: −48%, P < 0.001; P21: −56,3%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3E–H).

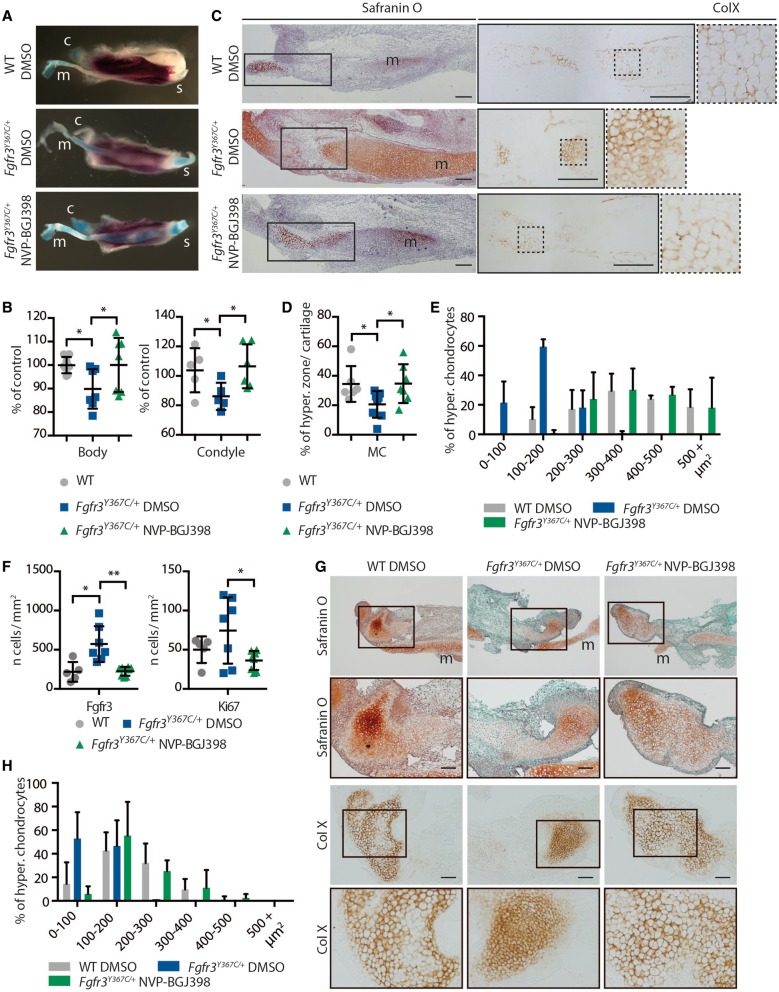

Tyrosine kinase inhibition corrects primary and secondary cartilages defects in Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos

To test the hypothesis that the mandibular hypoplasia and dysmorphogenesis observed in children with ACH and Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice are direct consequences of an overactive FGFR3, we analyzed the effect on mandibular development and growth of pharmacological inhibition of FGFRs using NVP-BGJ398, a pan-specific FGFR inhibitor (30). We first developed an ex vivo system of mandible explant cultures, similar to the femur explant cultures we used to test pharmacological approaches of FGFR inhibition (11,32,35). We isolated the mandible from WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos at E16.5, dissected the mandibles into two hemi-mandibles and cultured those separately for 6 days. One hemi-mandible was treated with NVP-BGJ398, whereas the other served as control. As expected, the body and condyle of hemi-mandible from Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos treated with DMSO were smaller than those of WT hemi-mandibles also treated with DMSO (−10,1%, P < 0.05; −18%, P < 0.05 respectively, Fig. 4A and B). Incubation with NVP-BGJ398 of Fgfr3Y367C/+ hemi-mandibles led to an increase in mandible body (+11%, P < 0.05) and condylar neck (+26%, P < 0.05) size, reaching the size of cultured WT hemi-mandibles treated with DMSO (Fig. 4A and B).

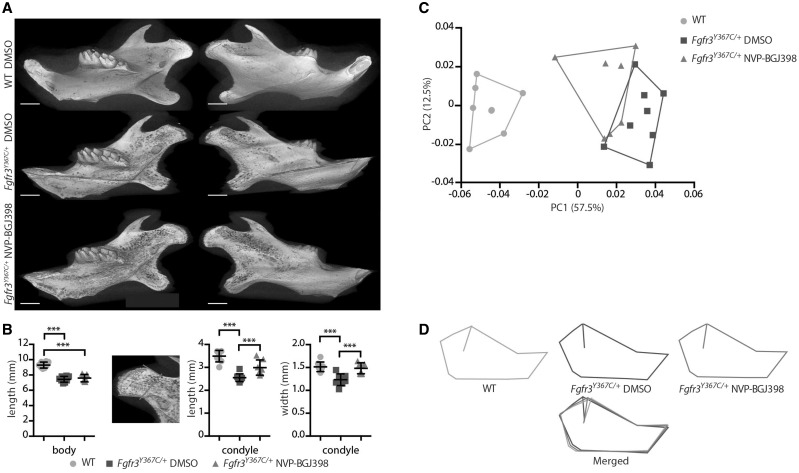

Figure 4.

NVP-BGJ398 corrects primary and secondary cartilages defects in ex vivo cultures of mandibles from Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos. (A) Representative macroscopic views of hemi-mandibles from E16.5 WT or Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos, treated with DMSO or NVP-BGJ398 and cultured for 6 days, following alcian blue and alizarin red staining. Symphyseal (s), condylar (c) and Meckel’s (m) cartilages are indicated. (B) Mandibular body and condylar neck length of cultured hemi-mandibles (n ≥ 5 individuals for each genotype and treatment). Total length of the hemi-mandible was measured as well as the length of the condylar and symphyseal cartilages (identified with the alcian blue staining). The length of the body was calculated as the total length minus the condylar and symphyseal cartilages. (C) Histological staining (Safranin’O) and immunostaining for ColX of cultured hemi-mandibles. An enlargement of the ColX immunostaining highlights the modification in the size of hypertrophic chondrocytes in MC of Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos and the correction of the defect with NVP-BGJ398 (scale bar = 200 μm). (D) Measurement of the ColX positive zone inside MC of cultured hemi-mandibles (n ≥ 6 individuals for each genotype and treatment). (E) Mean percentage of hypertrophic chondrocytes for different size categories (expressed in μm2) inside MC of cultured hemi-mandibles (n ≥ 50 cells from n ≥ 5 individuals for each genotype and treatment). (F) Mean number of immune positive cells for Fgfr3 or Ki67 inside MC of WT, Fgfr3Y367C/+ DMSO and Fgfr3Y367C/+ NVP-BGJ398 E16.5 embryos (n ≥ 5 individuals for each genotype). (G) Histological staining (Safranin’O) and immunostaining for Collagen X of cultured hemi-mandibles condylar cartilage (scale bar = 100 μm). Meckel’s cartilage (m) is indicated. (H) Mean percentage of hypertrophic chondrocytes for different size categories (expressed in μm2) inside condylar cartilage of cultured hemi-mandibles (n ≥ 50 cells from n ≥ 5 individuals for each genotype and treatment). Data shown as mean with SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Increases in mandible length with NVP-BGJ398 treatment were associated with the correction of chondrocyte defects observed in primary and secondary mandibular cartilages of Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos. Although the size of MC hypertrophic zone relative to the size of the cartilage was clearly reduced in Fgfr3Y367C/+ hemi-mandible treated with DMSO compared to WT (−40.2%, P < 0.05), this zone expanded following Fgfr3 inhibition in mutant mandible (+68.3%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 4C and D). This expansion was associated with an increased size of individual hypertrophic chondrocytes in hemi-mandible from Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos treated with NVP-BGJ398 (+165% compared to Fgfr3Y367C/+ treated with DMSO, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4C and E). We noted an increased replacement of MC by bone in the treated mandibles, compared to the untreated Fgfr3Y367C/+ mandible, rescuing the extinction delay of MC observed in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice. The kinase inhibitor also corrected the overexpression of Fgfr3 and the increased proliferation of chondrocytes in MC of Fgfr3Y367C/+ hemi-mandible (Fig. 4F).

In the condylar cartilage, similar changes were observed. Treatment with NVP-BGJ398 increased the size of the cartilage hypertrophic zone and the size of individual hypertrophic chondrocytes in condyles of Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos (+98.4%, P < 0.0005 compared to condyles from Fgfr3Y367C/+ hemi-mandibles treated with DMSO) (Fig 4G and H).

Altogether, we observed that the reduction of Fgfr3 activity with NVP-BGJ398 corrected the defective growth and cellular defects observed in the presence of an overactive Fgfr3. As those improvements occurred in the absence of any systemic regulation (ex vivo explants), the effect of the inhibitor is likely direct. This reinforces the view that the cartilage defects are responsible for the mandibular hypoplasia.

Tyrosine kinase inhibition improves the mandibular dysmorphogenesis and the size of the condyle in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice

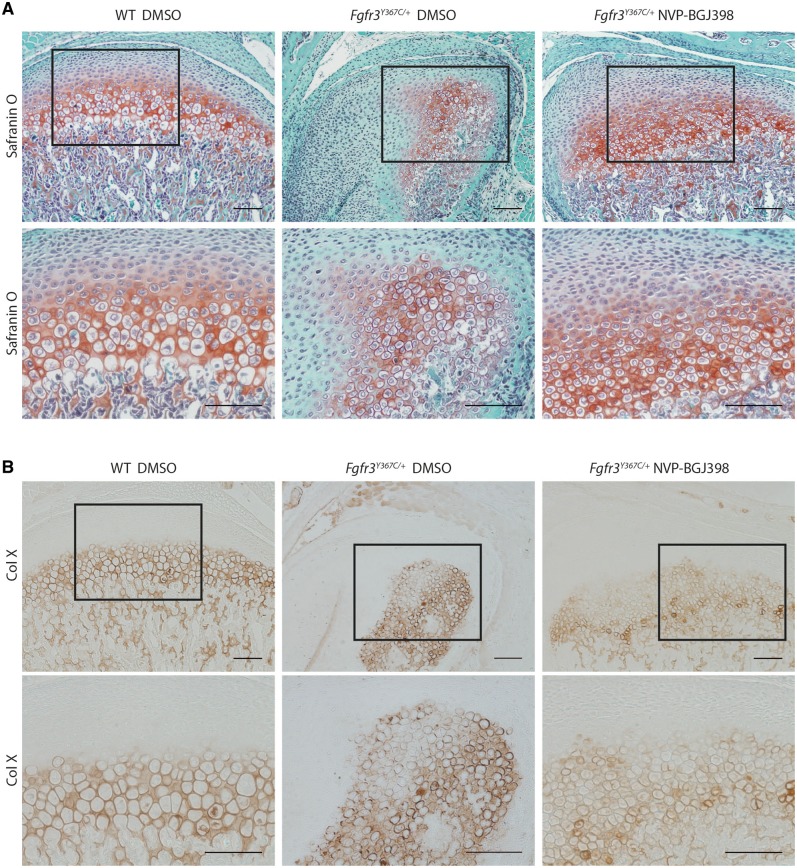

Finally, we tested the potential benefit of a pharmacological use of tyrosine kinase inhibitor to correct in vivo the mandibular hypoplasia and dysmorphogenesis of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice. We performed daily subcutaneous injection of either NVP-BGJ398 (2 mg/kg) or vehicle on 1-day-old mice from P0 to P15 (11). The mandibles of P16 mice were then imaged by micro-CT. As in the ex vivo experiments, we observed phenotypic changes of the condylar neck in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice treated with NVP-BGJ398 compared to Fgfr3Y367C/+ littermates treated with DMSO. The length (+20.9%, P < 0.005) and width (+22%, P < 0.005) of the condylar neck were increased by the reduction of the over-activation of FGFR3 (n = 7, n = 8 and n = 7 for WT vehicle, Fgfr3Y367C/+ vehicle and Fgfr3Y367C/+ NVP-BGJ398, respectively) (Fig. 5A and B). As expected, the length of mandible body was unchanged because MC had already been replaced by bone at the start of the injections. We confirmed the positive effect of NVP-BGJ398 on condylar cartilage with histological sections of the condyles (Fig. 6A and B). The PCA of the Procrustes shape coordinates of the landmarks measured on all mandibles was also run. As for P21 mice, PC1 separated the WT vehicle and the Fgfr3Y367C/+ vehicle mice (Fig. 5C and D). The Fgfr3Y367C/+ NVP-BGJ398 mice occupied a somewhat intermediate position though they overlap with the Fgfr3Y367C/+ vehicle mice (Fig. 5C and D). P-values from permutation tests (10 000 permutation rounds) for Mahalanobis distances among groups showed that the Fgfr3Y367C/+ NVP-BGJ398 mice were significantly different in the shape of the mandible from either the Fgfr3Y367C/+ vehicle mice or the WT vehicle. When comparing the centroid size (CS) used as a proxy for overall size of the mandible, WT mice displayed significantly larger mandible than Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice treated with the vehicle (t = −6.96; P < 0.005) or NVP-BGJ398 (t = −7.35; P < 0.005). Fgfr3Y367C/+ NVP-BGJ398 mice did not display significantly larger mandible than the Fgfr3Y367C/+ vehicle mice (t = −0.0887; P = 0.931). These data confirm that the length of the mandible was not corrected by the treatment, but that the overall shape of the mandible of Fgfr3Y367C/+ was improved with NVP-BGJ398.

Figure 5.

NVP-BGJ398 improves in vivo condyle growth of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice. (A) Representative 3D reconstructions of 16-day-old WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice treated with DMSO or NVP-BGJ398 for 15 days since P01 (scale bar = 1 mm). (B) Measurement of the mandible body and the condyle length and width of WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice treated with DMSO or NVP-BGJ398 (n ≥ 6 individuals for each genotype and treatment). Total length of the mandible and the length of the condyle were measured . The length of the body was calculated as the total length minus the condyle. (C and D) PCA of the Procrustes shape coordinates of the landmarks measured on mandibles of WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice treated with DMSO or NVP-BGJ398 and corresponding superimposition (n ≥ 6 individuals for each genotype and treatment). Data shown as mean with SD; ***P < 0.005.

Figure 6.

NVP-BGJ398 improves in vivo the chondrocyte differentiation in condyle of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice. Histological staining (Safranin’O) (A) and immunostaining for collagen X (B) of condylar cartilage of 16-day-old WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice treated with DMSO or NVP-BGJ398 for 15 days since P01 (scale bar = 100 μm).

Discussion

Deviation from normal mandible growth can strongly affect the masticatory and respiratory functions, speech and aesthetic appearance of the face (41,43), and mandibular cartilages are recognized as critical growth centers for the mandible. Although many cartilages are affected in FGFR3-related chondrodysplasias, most strikingly the cartilaginous growth plate in the growing skeleton, mandibular cartilages and their impact on mandible growth had never been investigated in ACH. Our hypothesis was that mandibular cartilages would be affected by FGFR3-activating mutations, similar to other cartilages, and that these defects would cause modifications in the shape, size and/or position of the mandible.

We first observed differences in the size and shape of the mandible between ACH and control children. The mandible as a whole, or subunits such as the mandibular body and ramus were reduced in size at all ages in children with ACH and morphometric analysis revealed modifications in the shape of the ramus. Comparable changes were present in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice, and in both children and mice, the mandibular hypoplasia worsened with age. Our findings illustrate again the similarity of this mouse model with ACH.

In addition to ACH, FGFR3-activating mutations cause four other types of chondrodysplasia (hypochondroplasia, severe achondroplasia with developmental delay and acanthosis nigricans, and TD type I and II) (1,2) and two types of craniosynostoses (MS and Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans) (44). The presence of mandible abnormalities in these diseases has rarely been studied. A report showed mandibular clefting in a case of TD I (28), two cephalometric studies in adult ACH patients reported opposite results concerning the size of the mandible [normal for Cohen et al. (26) or decreased for Cardoso et al. (27)], whereas another study showed that MS patients had shorter mandibular body length than controls (29). Several mouse lines carrying Fgfr3 activating mutations have been generated but a very few comprehensive analysis of the mandible are available. The homozygous Fgfr3 G380R mouse, a model for ACH, has a reduced mandible length (79% of controls) (45), and the homozygous Fgfr3 P244R mouse, a model for MS, has a hypomorphic condyle (46).

The FGFR3 mutations responsible for chondrodysplasias and craniosynostoses were until recently known to primarily affect different ossification processes (endochondral versus membranous), but as observed in ACH (3), FGFR3 over-activation can consistently disturbs both ossification processes. The ossification of the mandible relies on these two types, the body being formed by membranous ossification, whereas the ramus is mainly formed by endochondral ossification. If the effect of FGFR3 mutations responsible for ACH on the ramus is expected, it is intriguing that the same mutations can affect the size of the mandibular body. In order to understand what led to these changes we studied a primary (Meckel’s) and a secondary (condylar) cartilage. The exact role of MC is not yet fully understood as it disappears before birth and only marginally participates in the ossification process of the mandible (47). It could play a role in the elongation of the mandible body as exemplified by the severe micrognathia present when MC is strongly perturbed as in the case of Sox9 haploinsufficiency (48) or deletion of Snai1 and Snai2 (24). Here, we found that Fgfr3 over-activation disturbed the differentiation of chondrocytes in MC. The size of the hypertrophic zone was markedly shortened, as was the size of individual hypertrophic chondrocytes. The same defects were observed in the growth plate of ACH patients (6) and Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice (10,40). As the chondrocytes differentiate in the growth plate, the volume enlargement to become hypertrophic determines the size of the growth plate elongation (49–51). The same mechanism could occur in MC and the disruption of MC chondrocytes differentiation caused by FGFR3 over-activation could lead to the shortening of the mandible body. Supporting this view, we observed that reduction of the tyrosine kinase activity of FGFR3 with NVP-BGJ398 not only corrected the hypertrophic chondrocyte phenotype in mandible ex vivo cultures but also improved the shortening of the mandible of Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos. In contrast, the same molecule had no effect on the mandible body once MC was replaced by bone. We assume that this is due to the disappearance of MC before birth and, to us, reinforces the importance of MC in the elongation of the mandible. In mice of this age, ossification of the symphyseal is limited and therefore contributes marginally to the elongation of the mandible body (52).

The activity of FGFR3 must be precisely tuned for normal mandible elongation because the injection of dominant negative (DN) form of FGFR3 in the chick embryo leads to the truncation or shortening of MC (22). In the same study, the DN form reduced the proliferation of the cells in MC, whereas in our study, we observed that it was markedly increased by the activating mutation. Increased chondrocyte proliferation was also observed in the growth plate of embryos carrying either the Fgfr3 Y367C or K644E mutations (40,53). In MC, the expression of Fgfr3 was also increased by the Y367C Fgfr3 mutation. It could be the result of a prolonged half time of the protein because the mutation of the transmembrane domain could delay the turnover and degradation of the activated receptor (54,55).

FGFR3 mutations responsible for ACH could also affect the ossification of the mandibular process that was delayed in Fgfr3Y367C/+ embryos. It could be a consequence of the defective MC homeostasis and subsequent initiation of ossification. Alternatively, mesenchymal cells lateral to MC that directly differentiate into osteoblasts (20) could be independently affected by FGFR3 activation. Further work is needed to determine whether this delay affects mandible bone mass acquisition during growth, as reported in long bones (40,56).

Secondary cartilages are sites of late prenatal and early postnatal growth and eventually ossify. Here, we focused on the condylar cartilage. It develops adjacent to the intramembranous bone of the mandible, distinct from MC and in contrast with MC, directly contributes to the formation of the ramus by endochondral ossification and persists postnatally to function as a growth center (42). Genetic defects in chondrogenesis can cause abnormal condylar growth as in Pierre Robin sequence (41), an entity associated with genetic defects of SOX9 (57). We found that children with ACH had shorter condylar neck, a feature also found in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice. Histological analysis of the condyle in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice revealed a disturbed cartilage where the hypertrophic chondrocytes were smaller and the hypertrophic zone shortened, as in MC or in the growth plate of the same mice (10). Altered differentiation of chondrocyte is also present in condyles of TD infants (58) and in the hypolpastic condyle of homozygous Fgfr3 P244R mice (46). Here, cultures of hemi-mandibles and in vivo experiments with partial inhibition of Fgfr3 activity showed that it is likely that the defective chondrocyte differentiation and proliferation directly contributes to the reduced elongation of the condyle. The persistence of the condylar cartilage postnatally allowed us to observe that in vivo tyrosine kinase inhibition rescue condylar growth in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice, increasing its length by 21% after 15 days of treatment. The same treatment improved the growth of appendicular and axial skeletons with a similar magnitude of change of long bones (11).

Current treatments of maxillofacial deformities and skeletal dysplasia are primarily surgical and can require multiple interventions during childhood (59,60). Innovative pharmacological treatments of these diseases are needed and reducing the excessive activity of the FGFR3 receptor in FGFR3-related chondrodysplasias or craniosynostoses with specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as NVP-BGJ398, is an appealing approach. It potentially targets all downstream signaling pathways of the receptor, and in this aspect, NVP-BGJ398 has been shown to normalize in vitro and in vivo ERK1/2 and PLCγ pathways (11). Our pre-clinical experiments showed here that this inhibitor enters mandibular cartilages and improves craniofacial growth.

In summary, we showed in this article that a FGFR3 gain-of-function mutation disturbs the development and growth of the mandible, via structural anomalies of Meckel’s and condylar cartilages. These anomalies are likely related to the defective chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation, and the tyrosine kinase inhibitor NVP-BGJ398 corrects these defects and improves condyle growth. This suggests that postnatal treatment with the molecule could be a therapeutic strategy to improve mandible growth in ACH and others FGFR3-related disorders.

Materials and Methods

Human subjects

All patients with ACH (n = 12, mean age = 32.4 months) or age-matched controls (n = 14, mean age = 32.4 months) were examined and followed at the Craniofacial Surgery Unit of Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital. Ethics approvals were obtained from the institutional review Board of Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital.

Mouse models

All the experiments were conducted in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice, a mouse model that display parts of the clinical hallmarks of ACH (32), or WT littermates, used as controls. WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice were generated by crossing Fgfr3neoY367C mice (10) and Cmv-Cre mice (61). The mutant mice express the c.1100A > G (p.Tyr367Cys) mutation corresponding to the c.1118A > G (p.Tyr373Cys) in TD. All mice were on a C57BL/6 background. Mice were genotyped by PCR of tail DNA as described previously (10). Experimental animal procedures and protocols were approved by the French Animal Care and Use Committee.

CT images of human patients and mice

Human patients CT images were produced by a 64-slice CT system (LightSpeed VCT; General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA). The images were reconstructed in 3D using Carestream PACS v11.0 software (Carestream Health, Rochester, NY, USA). Cephalometric analysis of the mandible was carried on sagittal views of the 3D reconstructions.

Following 15 days of NVP-BGJ398 treatment, Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice and their control littermates were sacrificed, and the whole heads were imaged using a μCT40 Scanco vivaCT42 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). The following settings were used: integration time: 300 ms, 45 E(kVp), 177 µA. The mandible images were reconstructed in 3D using OsiriX 64-bit version software (Pixmeo, Bernex, Switzerland).

Morphometric analysis

The samples consisted of CT images of patients with ACH and unaffected age-matched individuals, and of high-resolution CT images of 7 P21 Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice and seven control littermates. Three-dimensional coordinates of 10 landmarks were recorded on the 3D reconstructed mandibles of humans and mice and analyzed with geometric morphometric methods. Standardization for position, scale and orientation was obtained by Procrustes superimposition (62,63), and shape information (Procrustes coordinates) and size (CS (63)) were extracted. Shape information was subsequently analyzed by PCA [for more information on geometric morphometrics applied to craniofacial birth defect, see (31)]. Wireframes are used to visualize the shape differences between positive and negative values of PC 1 corresponding to control and ACH mandibles respectively. Geometric morphometric analyses were run with Morpho J (64).

Whole-mount Alcian blue-alizarin red staining

Mandibles of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice and their WT littermates at E16.5, E18.5, P0 and P21 were fixed in 95% ethanol and then stained with Alizarin Red and Alcian Blue, cleared by KOH treatment and stored in glycerol according to standard protocols. Size of the mandibles and the condyles was measured on images captured with an Olympus PD70-IX2-UCB using CellSens software (Olympus). Total length of the mandible as well as the length of the condylar and symphyseal cartilages were measured (identified with the alcian blue staining). The length of the body was calculated as the total length minus the condylar and symphyseal cartilages.

Immunohistochemistry

Mandibles of Fgfr3Y367C/+ and their WT littermates at E16.5, E18.5, P0 and P21 were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 5 °C for 24 hours and decalcified in 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0) overnight or up to 1 week, depending on the age of the mice, and then dehydrated in graded series of ethanol, cleared in xylenes and embedded in paraffin. Five micometre sagittal sections were cut and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), safranin-O or subjected to immunohistochemical staining using standard protocols using an antibody against Collagen X (1:50 dilution; BIOCYC, Luckenwalde, Germany), FGFR3 (1:250; Sigma-Aldrich Co, St. Louis, MO, USA) or Ki67 (1:3000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) using the Dako Envision kit (Dako North America, Inc., CA, USA). Images were captured with an Olympus PD70-IX2-UCB microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and morphometry was performed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Ex vivo experiments

Mandibles from WT and Fgfr3Y367C/+ E16.5 embryos were dissected and cut at the symphysis to separate the two hemi-mandibles. For each embryo, the two hemi-mandibles were incubated for 5 days in DMEM medium with antibiotics and 0.2% BSA (Sigma), one supplemented with NVP-BGJ398 (100 nm), whereas the other served as control and was supplemented with DMSO (0.1%). The length of the hemi-mandibles was measured at the end of time course, following whole-mount Alcian blue-alizarin red staining.

In vivo experiments

Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice were 1-day old at treatment initiation and received daily subcutaneous administrations of NVP-BGJ398 at 2 mg/kg body weight or vehicle (HCl 3.15 mm, DMSO 2%) for 15 days. Cartilage and bone analyses were thus performed in 16-day-old male and female mice. Experimental animal procedures and protocols were approved by the French Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistical analysis

Differences between experimental groups were assessed using analysis of variance or Mann–Whitney test. The significance threshold was set at P ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad PRISM (v5) (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). All values are shown as mean ± SD.

Authors‘ Contributions

M.B.D., D.K.E., Y.H. and L.L.M. designed research. M.B.D, D.K.E., Y.H., V.E., E.G., N.K. and C.B.L. performed research. I.K., M.K. and D.G.P. contributed new reagents. M.Z. and F.D.R. contributed human data. M.B.D., Y.H. and F.D.R. analyzed mouse and human data. M.B.D., D.K.E., Y.H. and L.L.M. prepared the figures and wrote the article.

Conflict of Interest statement. IK, DGP and MK work for Novartis. The other authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Funding

Comité d’interface INSERM/Odontologie (MBD), YH was partly funded by the French National Agency of Research (ANR) through the program “Investissements d’avenir” (ANR-10-LABX-52). This project received a state subsidy managed by the National Research Agency under the “Investments for the Future” program bearing the reference ANR-10-IHU-01, the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme Under grant agreement no. 602300 (Sybil) the Fondation des Gueules Cassées and the Association des Personnes de Petites Tailles. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by INSERM U1163.

References

- 1.Baujat G., Legeai-Mallet L., Finidori G., Cormier-Daire V., Le Merrer M. (2008) Achondroplasia. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol, 22, 3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horton W.A., Hall J.G., Hecht J.T. (2007) Achondroplasia. Lancet, 370, 162–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Rocco F., Biosse Duplan M., Heuzé Y., Kaci N., Komla-Ebri D., Munnich A., Mugniery E., Benoist-Lasselin C., Legeai-Mallet L. (2014) FGFR3 mutation causes abnormal membranous ossification in achondroplasia. Hum. Mol. Genet, 23, 2914–2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rousseau F., Bonaventure J., Legeai-Mallet L., Pelet A., Rozet J.M., Maroteaux P., Le Merrer M., Munnich A. (1994) Mutations in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in achondroplasia. Nature, 371, 252–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ornitz D.M. (2005) FGF signaling in the developing endochondral skeleton. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev., 16, 205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Legeai-Mallet L., Benoist-Lasselin C., Munnich A., Bonaventure J. (2004) Overexpression of FGFR3, Stat1, Stat5 and p21Cip1 correlates with phenotypic severity and defective chondrocyte differentiation in FGFR3-related chondrodysplasias. Bone, 34, 26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Q., Green R.P., Zhao G., Ornitz D.M. (2001) Differential regulation of endochondral bone growth and joint development by FGFR1 and FGFR3 tyrosine kinase domains. Dev. Camb. Engl, 128, 3867–3876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segev O., Chumakov I., Nevo Z., Givol D., Madar-Shapiro L., Sheinin Y., Weinreb M., Yayon A. (2000) Restrained chondrocyte proliferation and maturation with abnormal growth plate vascularization and ossification in human FGFR-3(G380R) transgenic mice. Hum. Mol. Genet, 9, 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsushita T., Wilcox W.R., Chan Y.Y., Kawanami A., Bukulmez H., Balmes G., Krejci P., Mekikian P.B., Otani K., Yamaura I., et al. (2008) FGFR3 promotes synchondrosis closure and fusion of ossification centers through the MAPK pathway. Hum. Mol. Genet, 18, 227–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pannier S., Couloigner V., Messaddeq N., Elmaleh-Bergès M., Munnich A., Romand R., Legeai-Mallet L. (2009) Activating Fgfr3 Y367C mutation causes hearing loss and inner ear defect in a mouse model of chondrodysplasia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1792, 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komla-Ebri D., Dambroise E., Kramer I., Benoist-Lasselin C., Kaci N., Le Gall C., Martin L., Busca P., Barbault F., Graus-Porta D., et al. (2016) Tyrosine kinase inhibitor NVP-BGJ398 functionally improves FGFR3-related dwarfism in mouse model. J. Clin. Invest, 10.1172/JCI83926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts W.E., Hartsfield J.K. (2004) Bone development and function: genetic and environmental mechanisms. Semin. Orthod, 10, 100–122. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon A., Hoyte D., Rönning O. (1997) Fundamentals of craniofacial growth Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen H., Liu C.T., Yang S.S., Opitz J.M. (1981) Achondrogenesis: A review with special consideration of achondrogenesis type II (langer-saldino). Am. J. Med. Genet, 10, 379–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mansour S., Offiah A.C., McDowall S., Sim P., Tolmie J., Hall C. (2002) The phenotype of survivors of campomelic dysplasia. J. Med. Genet, 39, 597–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schipani E., Langman C.B., Parfitt A.M., Jensen G.S., Kikuchi S., Kooh S.W., Cole W.G., Jüppner H. (1996) Constitutively activated receptors for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide in Jansen’s metaphyseal chondrodysplasia. N. Engl. J. Med, 335, 708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkie A.O., Slaney S.F., Oldridge M., Poole M.D., Ashworth G.J., Hockley A.D., Hayward R.D., David D.J., Pulleyn L.J., Rutland P. (1995) Apert syndrome results from localized mutations of FGFR2 and is allelic with Crouzon syndrome. Nat. Genet, 9, 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lajeunie E., El Ghouzzi V., Le Merrer M., Munnich A., Bonaventure J., Renier D. (1999) Sex related expressivity of the phenotype in coronal craniosynostosis caused by the recurrent P250R FGFR3 mutation. J. Med. Genet, 36, 9–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rice D.P.C., Rice R., Thesleff I. (2003) Fgfr mRNA isoforms in craniofacial bone development. Bone, 33, 14–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu K., Karuppaiah K., Ornitz D.M. (2015) Mesenchymal fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling regulates palatal shelf elevation during secondary palate formation: Mesenchymal FGFR Regulates Palatal Shelf Elevation. Dev. Dyn., 244, 1427–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Havens B.A., Rodgers B., Mina M. (2006) Tissue-specific expression of Fgfr2b and Fgfr2c isoforms, Fgf10 and Fgf9 in the developing chick mandible. Arch. Oral Biol, 51, 134–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Havens B.A., Velonis D., Kronenberg M.S., Lichtler A.C., Oliver B., Mina M. (2008) Roles of FGFR3 during morphogenesis of Meckel’s cartilage and mandibular bones. Dev. Biol., 316, 336–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Frutos C.A., Vega S., Manzanares M., Flores J.M., Huertas H., Martínez-Frías M.L., Nieto M.A. (2007) Snail1 is a transcriptional effector of FGFR3 signaling during chondrogenesis and achondroplasias. Dev. Cell, 13, 872–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray S.A., Oram K.F., Gridley T. (2007) Multiple functions of Snail family genes during palate development in mice. Dev. Camb. Engl., 134, 1789–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Z., Lavine K.J., Hung I.H., Ornitz D.M. (2007) FGF18 is required for early chondrocyte proliferation, hypertrophy and vascular invasion of the growth plate. Dev. Biol., 302, 80–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen M.M., Walker G.F., Phillips C. (1985) A morphometric analysis of the craniofacial configuration in achondroplasia. J. Craniofac. Genet. Dev. Biol. Suppl., 1, 139–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardoso R., Ajzen S., Andriolo A.R., de Oliveira J.X., Andriolo A. (2012) Analysis of the cephalometric pattern of Brazilian achondroplastic adult subjects. Dent. Press J. Orthod, 17, 118–129. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuncer O., Caksen H., Kirimi E., Kayan M., Ataş B., Odabaş D. (2004) A case of thanatophoric dysplasia type I associated with mandibular clefting. Genet. Couns. Geneva Switz, 15, 95–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ridgway E.B., Wu J.K., Sullivan S.R., Vasudavan S., Padwa B.L., Rogers G.F., Mulliken J.B. (2011) Craniofacial growth in patients with FGFR3Pro250Arg mutation after fronto-orbital advancement in infancy. J. Craniofac. Surg., 22, 455–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guagnano V., Furet P., Spanka C., Bordas V., Le Douget M., Stamm C., Brueggen J., Jensen M.R., Schnell C., Schmid H., et al. (2011) Discovery of 3-(2,6-dichloro-3,5-dimethoxy-phenyl)-1-{6-[4-(4-ethyl-piperazin-1-yl)-phenylamino]-pyrimidin-4-yl}-1-methyl-urea (NVP-BGJ398), a potent and selective inhibitor of the fibroblast growth factor receptor family of receptor tyrosine kinase. J. Med. Chem, 54, 7066–7083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heuzé Y., Boyadjiev S.A., Marsh J.L., Kane A.A., Cherkez E., Boggan J.E., Richtsmeier J.T. (2010) New insights into the relationship between suture closure and craniofacial dysmorphology in sagittal nonsyndromic craniosynostosis. J. Anat, 217, 85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorget F., Kaci N., Peng J., Benoist-Lasselin C., Mugniery E., Oppeneer T., Wendt D.J., Bell S.M., Bullens S., Bunting S., et al. (2012) Evaluation of the therapeutic potential of a CNP analog in a Fgfr3 mouse model recapitulating achondroplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet, 91, 1108–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frommer J., Margolies M.R. (1971) Contribution of Meckel’s cartilage to ossification of the mandible in mice. J. Dent. Res., 50, 1260–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimo T., Kanyama M., Wu C., Sugito H., Billings P.C., Abrams W.R., Rosenbloom J., Iwamoto M., Pacifici M., Koyama E. (2004) Expression and roles of connective tissue growth factor in Meckel’s cartilage development. Dev. Dyn. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat., 231, 136–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jonquoy A., Mugniery E., Benoist-Lasselin C., Kaci N., Le Corre L., Barbault F., Girard A.L., Le Merrer Y., Busca P., Schibler L., et al. (2012) A novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor restores chondrocyte differentiation and promotes bone growth in a gain-of-function Fgfr3 mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet, 21, 841–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kronenberg H.M. (2003) Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature, 423, 332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delezoide A.L., Benoist-Lasselin C., Legeai-Mallet L., Le Merrer M., Munnich A., Vekemans M., Bonaventure J. (1998) Spatio-temporal expression of FGFR 1, 2 and 3 genes during human embryo-fetal ossification. Mech. Dev, 77, 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishizeki K., Saito H., Shinagawa T., Fujiwara N., Nawa T. (1999) Histochemical and immunohistochemical analysis of the mechanism of calcification of Meckel’s cartilage during mandible development in rodents. J. Anat., 194, 265–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakakura Y. (2010) Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Extracellular Matrix Disintegration of Meckel’s Cartilage in Mice. J. Oral Biosci, 52, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pannier S., Mugniery E., Jonquoy A., Benoist-Lasselin C., Odent T., Jais J.P., Munnich A., Legeai-Mallet L. (2010) Delayed bone age due to a dual effect of FGFR3 mutation in Achondroplasia. Bone, 47, 905–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pirttiniemi P., Peltomäki T., Müller L., Luder H.U. (2009) Abnormal mandibular growth and the condylar cartilage. Eur. J. Orthod., 31, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen G., Darendeliler M.A. (2005) The adaptive remodeling of condylar cartilage—. A Transition from Chondrogenesis to Osteogenesis. J. Dent. Res., 84, 691–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Obwegeser H.L. (2001) Mandibular Growth Anomalies Springer Berlin Heidelberg. Berlin, Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vajo Z., Francomano C.A., Wilkin D.J. (2000) The molecular and genetic basis of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 disorders: the achondroplasia family of skeletal dysplasias, Muenke craniosynostosis, and Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans. Endocr. Rev, 21, 23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naski M.C., Colvin J.S., Coffin J.D., Ornitz D.M. (1998) Repression of hedgehog signaling and BMP4 expression in growth plate cartilage by fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Dev. Camb. Engl, 125, 4977–4988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yasuda T., Nah H.D., Laurita J., Kinumatsu T., Shibukawa Y., Shibutani T., Minugh-Purvis N., Pacifici M., Koyama E. (2012) Muenke syndrome mutation, FgfR3P244R, causes TMJ defects. J. Dent. Res., 91, 683–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harada Y., Ishizeki K. (1998) Evidence for transformation of chondrocytes and site-specific resorption during the degradation of Meckel’s cartilage. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.), 197, 439–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bi W., Huang W., Whitworth D.J., Deng J.M., Zhang Z., Behringer R.R., de Crombrugghe B. (2001) Haploinsufficiency of Sox9 results in defective cartilage primordia and premature skeletal mineralization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 98, 6698–6703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y., Spatz M.K., Kannan K., Hayk H., Avivi A., Gorivodsky M., Pines M., Yayon A., Lonai P., Givol D. (1999) A mouse model for achondroplasia produced by targeting fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 96, 4455–4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper K.L., Oh S., Sung Y., Dasari R.R., Kirschner M.W., Tabin C.J. (2013) Multiple phases of chondrocyte enlargement underlie differences in skeletal proportions. Nature, 495, 375–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y., Nishida S., Sakata T., Elalieh H.Z., Chang W., Halloran B.P., Doty S.B., Bikle D.D. (2006) Insulin-like growth factor-I is essential for embryonic bone development. Endocrinology, 147, 4753–4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sugito H., Shibukawa Y., Kinumatsu T., Yasuda T., Nagayama M., Yamada S., Minugh-Purvis N., Pacifici M., Koyama E. (2011) Ihh signaling regulates mandibular symphysis development and growth. J. Dent. Res., 90, 625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iwata T., Chen L., Li C., Ovchinnikov D.A., Behringer R.R., Francomano C.A., Deng C.X. (2000) A neonatal lethal mutation in FGFR3 uncouples proliferation and differentiation of growth plate chondrocytes in embryos. Hum. Mol. Genet., 9, 1603–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Narayana J., Horton W.A. (2015) FGFR3 biology and skeletal disease. Connect. Tissue Res., 56, 427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Legeai-Mallet L., Benoist-Lasselin C., Delezoide A.L., Munnich A., Bonaventure J. (1998) Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations promote apoptosis but do not alter chondrocyte proliferation in thanatophoric dysplasia. J. Biol. Chem, 273, 13007–13014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mugniery E., Dacquin R., Marty C., Benoist-Lasselin C., de Vernejoul M.C., Jurdic P., Munnich A., Geoffroy V., Legeai-Mallet L. (2012) An activating Fgfr3 mutation affects trabecular bone formation via a paracrine mechanism during growth. Hum. Mol. Genet, 21, 2503–2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benko S., Fantes J.A., Amiel J., Kleinjan D.J., Thomas S., Ramsay J., Jamshidi N., Essafi A., Heaney S., Gordon C.T., et al. (2009) Highly conserved non-coding elements on either side of SOX9 associated with Pierre Robin sequence. Nat. Genet, 41, 359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berraquero R., Palacios J., Rodríguez J.I. (1992) The role of the condylar cartilage in mandibular growth. A study in thanatophoric dysplasia. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop., 102, 220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cottrell D.A., Edwards S.P., Gotcher J.E. (2012) Surgical correction of maxillofacial skeletal deformities. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg., 70, e107–e136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shirley E.D., Ain M.C. (2009) Achondroplasia: manifestations and treatment. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg., 17, 231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Metzger D., Clifford J., Chiba H., Chambon P. (1995) Conditional site-specific recombination in mammalian cells using a ligand-dependent chimeric Cre recombinase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 6991–6995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rohlf F.J., Slice D. (1990) Extensions of the procrustes method for the optimal superimposition of landmarks. Syst. Biol., 39, 40–59. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dryden I., Mardia K. (1998) Statistical Shape Analysis. Wiley, Chichester. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klingenberg C.P. (2011) MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Mol. Ecol. Resour., 11, 353–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]