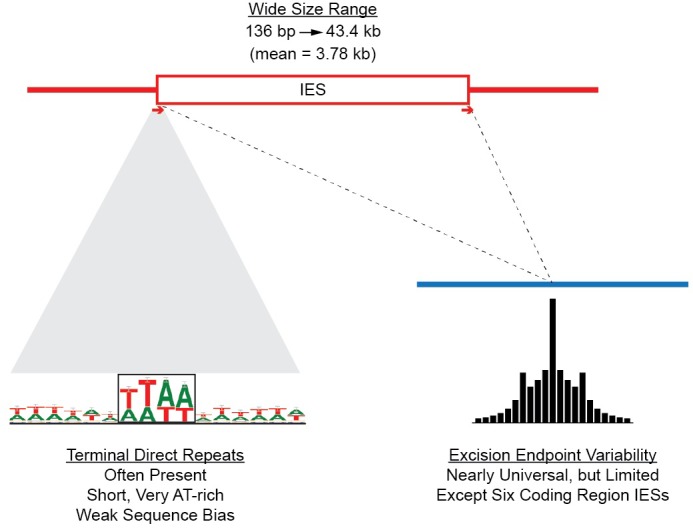

Short terminal direct repeats (TDRs) at IES termini were identified by examining alignments between the MIC and MAC genomes at these termini to identify alignment overlaps (i.e. short MAC sequences at precisely the site of excision that align to both precise ends of the IES). These results were confirmed by alignment of MIC sequencing reads to the MAC genome assembly (see

Figure 5—figure supplement 1C). (

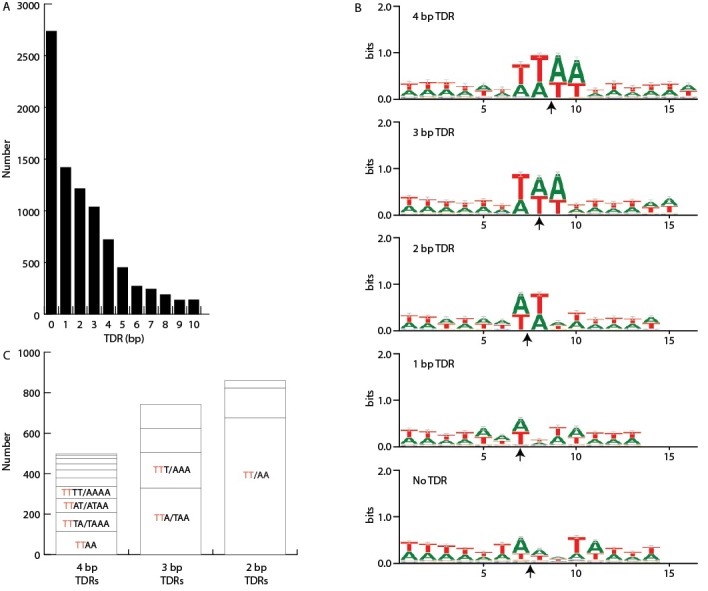

A) TDR length. Numbers of junctions with TDRs of the indicated lengths, showing that IESs with no TDR constitute the largest class. (

B) A+T richness. For each of the five TDR classes between 0 and 4 bp, the direct repeat (or two flanking bases, in the case of no overlap) plus six bases on either side were extracted from the MIC genome sequence and aligned (MAC-destined sequence to the left; MIC-limited sequence to the right). Each arrow indicates the center of the TDR (or, in the case of No TDR, the junction point). Sequence logos derived from the alignments show that the TDRs are more AT-rich than surrounding sequence. Bases within the four, three, and two base direct repeats are approximately 97% AT overall and the one base direct repeats are 92% AT, whereas the two bases flanking the 'zero overlap' junctions are 80% AT, similar to the adjacent sequence composition. (

C) Sequence pattern bias. In addition to overall AT-richness, the sequence patterns of the TDRs are not entirely random. We compared the frequency of each of the possible TDRs between 2 and 4 bp in length that consist of only As and Ts. Reverse complementary sequences were found to have approximately equal frequencies, as expected because the orientation of the sequenced strand is random, and they were grouped together. This makes for 10 groupings of 4 bp TDRs, 4 groupings of 3 bp TDRs, and 3 groupings of 2 bp TDRs. As shown in this panel, the frequencies of each grouping are unequal; the most common are: 4-mer TTAA (palindromic), 3-mer TTA/TAA, and 2-mer TT/AA (the latter two are pairs of reverse complementary sequences). Furthermore, it is notable that the four most common groupings of 4-mers all contain one member with a 5' TT dinucleotide (red font) and together account for two thirds of the total 4-mers. Likewise, the two (out of four total) 3-mer groupings containing a 5' TT dinucleotide account for two thirds of 3-mers, and the single TT/AA 2-mer grouping accounts for over three quarters of all 2-mers. These findings suggest that IES junctions have a slight bias in favor of beginning with TT and an extended weak consensus of 5'-TT(A)(A)−3', the most common 2, 3, and 4 bp TDRs (but far from the majority) including successively more of the consensus, from left to right.