Abstract

Using molecular modeling and rationally designed structural modifications, the multi-target structure–activity relationship for a series of ranitidine analogs has been investigated. Incorporation of a variety of isosteric groups indicated that appropriate aromatic moieties provide optimal interactions with the hydrophobic and π–π interactions with the peripheral anionic site of the AChE active site. The SAR of a series of cyclic imides demonstrated that AChE inhibition is increased by additional aromatic rings, where 1,8-naphthalimide derivatives were the most potent analogs and other key determinants were revealed. In addition to improving AChE activity and chemical stability, structural modifications allowed determination of binding affinities and selectivities for M1–M4 receptors and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE). These results as a whole indicate that the 4-nitropyridazine moiety of the JWS-USC-75IX parent ranitidine compound (JWS) can be replaced with other chemotypes while retaining effective AChE inhibition. These studies allowed investigation into multitargeted binding to key receptors and warrant further investigation into 1,8-naphthalimide ranitidine derivatives for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: Acetylcholinesterase, Alzheimers Disease, Multi-target, Ranitidine

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia in the elderly and currently there is no preventive or curative treatment available for the disease.1 A major symptom of AD is cognitive dysfunction with the pathological decline of cholinergic neurotransmission.2 Most of the current pharmaceutical treatments for AD are AChE inhibitors with donepezil (Fig. 1) being the only treatment approved by the FDA for all stages of Alzheimer’s disease.3,4 Unfortunately, currently approved drugs have been found to benefit only about half the individuals who take them and to only temporarily decrease symptoms.4 It has been gradually unveiled that cognitive dysfunction is multifactorial in nature5,6 and that in addition to AChE, other cholinergic targets such as butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE),7,8 muscarinic (M1–M4)9,10 and several nicotinic acetylcholine receptors11,12 are simultaneously involved in cognitive functioning. Targeting BuChE (in addition to AChE) should be advantageous in the context of AD since AChE levels go down while BuChE levels go up as the disease progresses.8 Furthermore, in the AD brain, increasing levels of AChE and BuChE correlate with the development of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.8,13,14 It has been hypothesized that AChE binds through its peripheral site to the nonamyloidogenic form of Aβ and acts as a pathological chaperone inducing a conformational transition to the amyloidogenic form.15,16 Accordingly, compounds that have the ability to bind and inhibit both the catalytic anionic site (CAS) and peripheral anionic site (PAS) of AChE (dual binding site AChEIs) could have pro-cognitive effects as well disease-modifying properties by inhibiting Aβ aggregation in AD.17 Moreover, during the progression of AD, cortical levels of BuChE are significantly increased and found within lesions that contain amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, suggesting that the enzyme might participate in the formation of these lesions. These observations indicate a potential disease modifying effect of compounds that inhibit BuChE.18 The muscarinic receptors are likely also significant as M2 selective antagonists have been hypothesized to be useful when given in conjunction with an AChE inhibitor to ameliorate the cognitive and psychotic symptoms inherent in the disease19, an important observation since more than half of patients with AD also suffer from psychotic symptoms in addition to severe cognitive deficits.20 Targeting the M2 receptor in particular is desirable since it is an autoreceptor that functions to diminish ACh release.9,10 In addition some studies suggest that the M1 and M3 receptors are desirable AD targets and recently their crystal structures have been solved.21

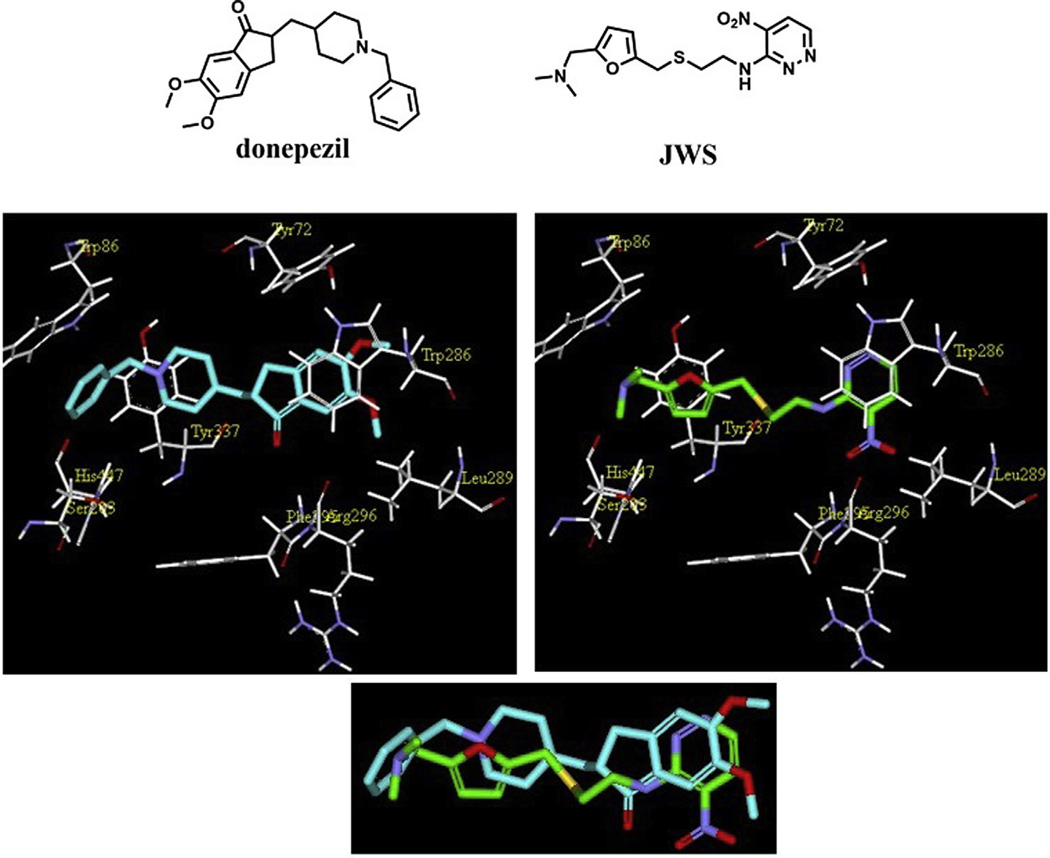

Figure 1.

Chemical structures (top panel) and predicted binding modes of donepezil (left) and JWS (right) generated by molecular docking. The bottom panel illustrates superposition of the binding modes of both compounds.

Cavalli et al.22 presented the terminology ‘multi-target-directed ligands’ (MTDLs) to describe single compounds ‘that are effective in treating complex diseases through their ability to interact with the multiple targets thought to be responsible for disease pathogenesis’, an important concept considering the multiple AD drug targets outlined above. The potential advantages of MTDLs relative to multiple single target formulations are that they avoid possible drug interactions with other active components and also offer a single and therefore less complex pharmacokinetic and ADMET profile during clinical development.23 In addition, MTDLs could also simplify therapeutic regimens and improve compliance, an important consideration, especially for cognitively impaired patients. Thus, MTDLs might present an effective avenue to provide optimal therapeutic effects for the treatment of cognitive and behavioral dysfunction in AD.23

Previous studies reported that JWS (Fig. 1) targets both AChE (IC50 = 470 nM) and M2 receptors (IC50 = 60 nM) concurrently.24–26 This compound has been also shown to improve information processing, attention, and memory in rodents and nonhuman primate models and therefore could potentially treat the cognitive and behavioral symptoms of AD.26 These data support JWS as a prototypical representative of a novel class of MTDLs for the therapy of cognitive dysfunction. The objective of this study is to explore structure–activity relationship of the JWS core structure and to further modify and optimize this series as a MTDL.

Docking of JWS into AChE

In order to guide the structural modification of ranitidine analogs, molecular docking protocols were utilized to predict binding interactions of this series and use this information to discover new chemical entities with an optimal multifunctional activity profile. Since JWS was initially synthesized as an AChE inhibitor and as crystal structures for this drug target are widely available, a protocol for docking ligands into the AChE crystal structure (PDB: 2H9Y)27 was validated and conformations for JWS and donepezil bound to the active site generated (Fig. 1).

The docking results obtained for JWS reveal that the dimethylamino group binds to the CAS, a key site of interaction previously observed to be necessary for potent AChE inhibition (Fig. 1). Since this group would be protonated at physiological pH it would therefore mimic the binding of the quaternary amine group in AChE with the CAS. The binding mode generated illustrates a variety of non-bonded interactions involved in the inhibition of ranitidine analogs to AChE, and in particular, emphasize the importance of the following: (1) van der Waals interactions between hydrophobic components and nonpolar amino acid residues: (2) cation–π interactions between the dimethylammonium group and Trp 86 at the CAS, (3) π–π interactions between rings at both ends of the molecules in this series and aromatic residues located at the PAS; (4) hydrogen bonds between key substituents (e.g., N(CH3)2, NO2) and polar residues at the PAS.

Since plausible binding modes were generated for JWS and donepezil in complex with AChE, these were further superimposed and a comparison of non-bonded interactions made (Fig. 1 bottom panel). JWS was found to have a pattern of binding to AChE similar to that of donepezil, which suggests that it may have similar pharmacological function to one of the most potent AChE inhibitors and widely used agents among the few approved pharmaceutical treatments for AD.

Synthesis and evaluation of N-(2-(((5-((dimethylamino)methyl)furan-2-yl)methyl)thio) ethyl)-4-nitropyridazin-3-amine (JWS) and analogs

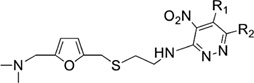

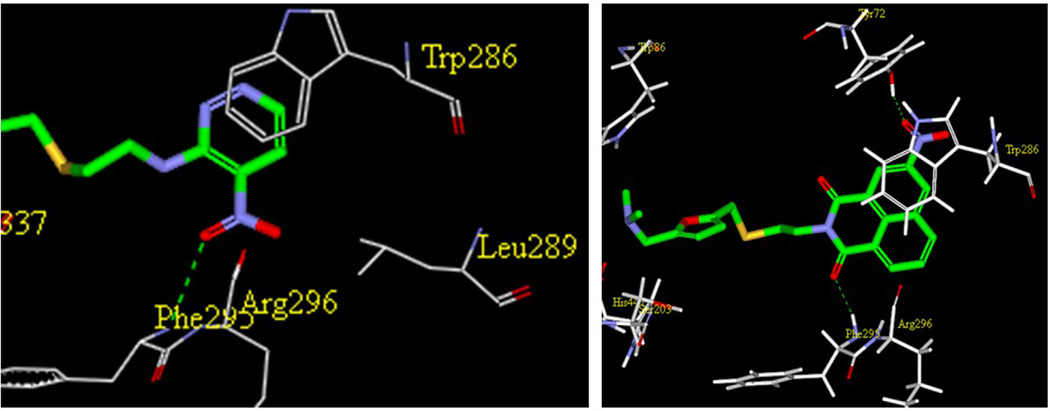

Previous studies have demonstrated that the 4-nitropyridazine moiety of JWS is critical to both its AChE inhibitory activity and also for its selectivity for muscarinic receptors.24 As a result of this observation, this group was selected for optimization to obtain more potent MTDLs. As shown in Figure 2, docking studies strongly suggest that the 4-nitropyridazine moiety binds to the PAS of AChE and that favorable van der Waals and π–π stacking interactions between the pyridazine ring and Trp286 and/or Tyr72 contribute to binding of JWS and AChE.

Figure 2.

Left Panel: The interactions (green lines) between the pyridazine group of JWS and the PAS of AChE. Right Panel: The binding conformation of compound 10 (R1 is methyl, R2 is phenyl) illustrating additional complementarity with Trp286.

Therefore, in order to further enhance the van der Waals contacts between the pyridazine ring and the PAS, it was reasoned that substitution of the ring with alkyl or aromatic groups might be effective. In addition, replacement of the pyridazine with isosteric ring systems was evaluated in order to explore structural variability and impact on π–π stacking interactions with the PAS. The synthesis and in vitro evaluation of such JWS analogs as potential cholinesterase inhibitors and muscarinic antagonists is reported to explore progress towards next generation MTDL as AD therapeutics.

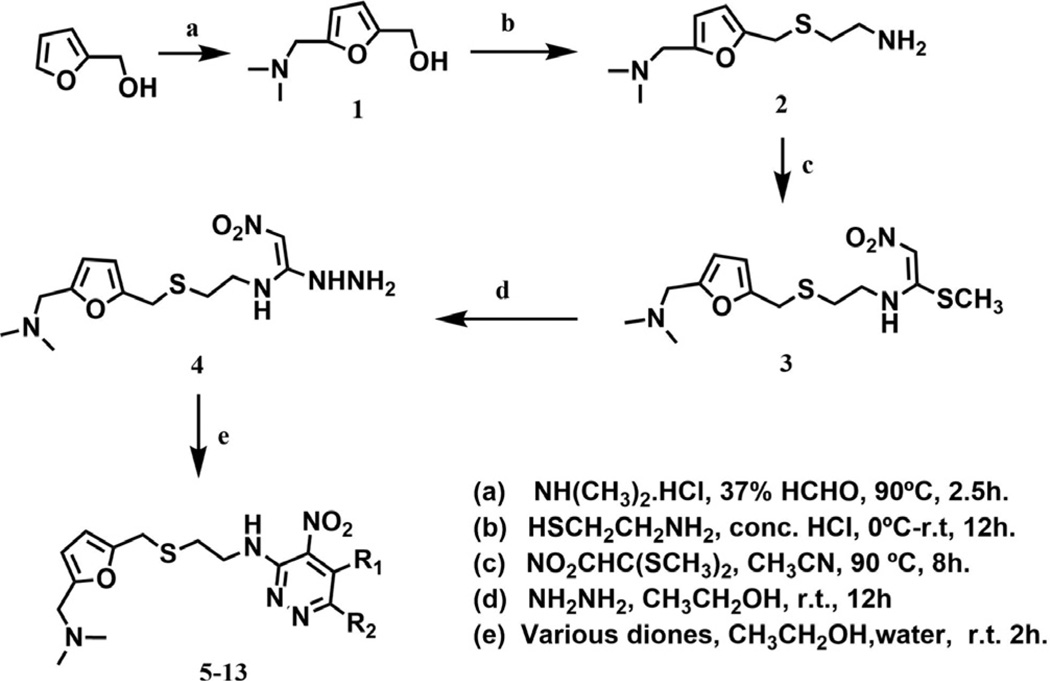

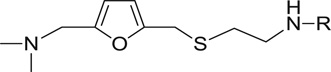

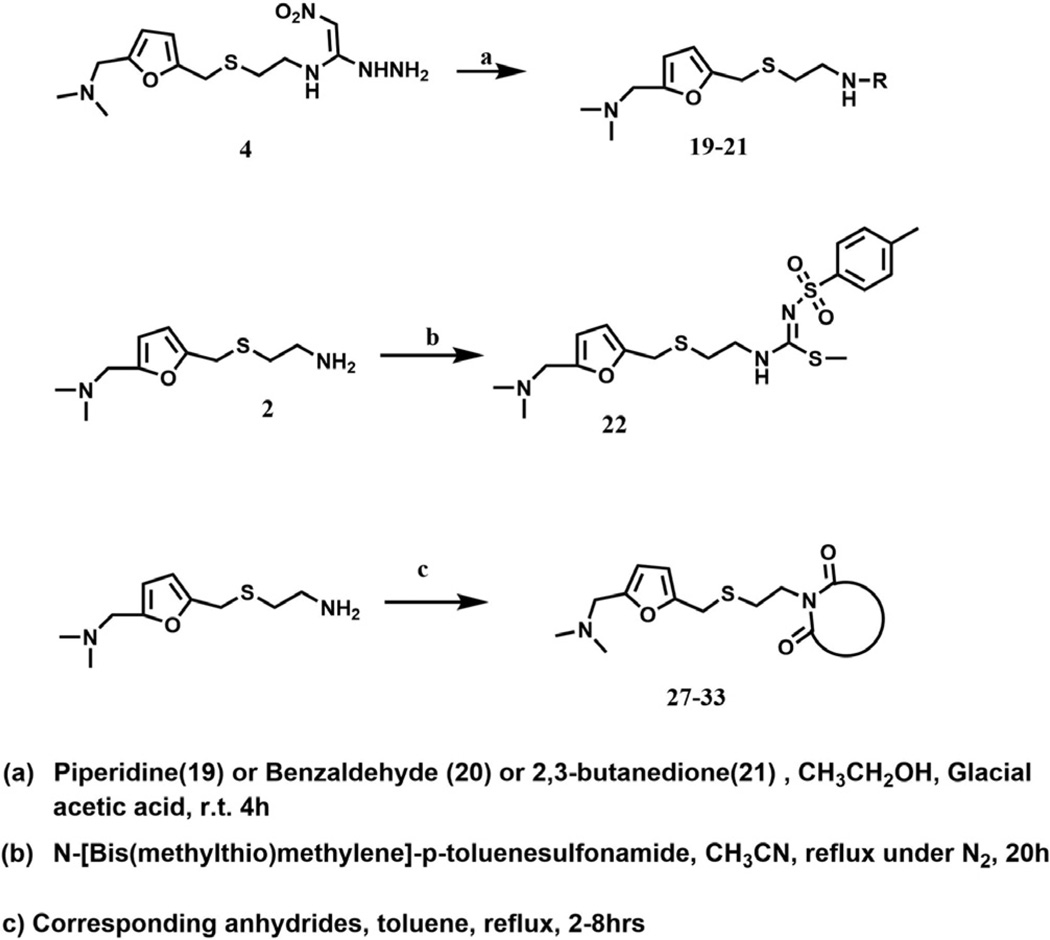

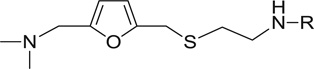

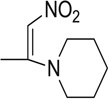

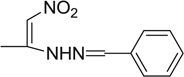

The procedure used for the synthesis of JWS analogs was adapted from that previously described24 and is shown in Scheme 1. In all cases, the formation of the 2-((5-((dimethylamino) methyl)furan-2-yl)methylthio)ethanamine backbone was accomplished through a Mannich reaction to generate intermediate 1 prior to substitution of the hydroxyl group with 2-thioethanolamine in concentrated hydrochloric acid to yield 2. Substitution of the two thiomethyl groups of 1,1-bis(methylthio)-2-nitroethylene was accomplished by reaction with compound 2 to generate intermediate 3, followed by reaction with hydrazine, to provide compound 4. A set of pyridazine analogs (compound 5–13) were synthesized utilizing the cyclization of the resulting hydrazine derivative, 4 with various diones. The activities of these 4-nitropyridazine analogs of JWS are summarized in Table 1. Compounds were evaluated in AChE,25,28 BuChe25,28 and M1–M4 assays29,30 (For Tables 1–3 and 1 µM compound was tested) as previously described. JWS analogs 5–7 possess small aliphatic groups at R1 and R2 and these were found to decrease activity. Compounds 8–13 contain phenyl substituted pyridazines and possess similar or better AChE inhibition than JWS, in particular compounds 10 (IC50 = 0.16 µM) and 12 (IC50 = 0.19 µM) which increase the AChE inhibition almost 3-fold relative to the unsubstituted nitropyridazine. Comparison of the combination of the single phenyl ring with either a hydrogen or small alkyl substituent at the two positions versus those with a phenyl ring at R1 and R2 produced consistent SAR data. The R1 phenyl was tolerated in each case without significantly affecting activity (JWS vs 9) and the phenyl ring at R2 in both cases resulted in more effective AChE inhibition (compare 7 and 8; 11 and 12). The predicted binding mode of 10 (Fig. 2), the most potent AChE inhibitor, indicates that the phenyl ring at R2 increases the π–π stacking interactions with Tyr72 and Trp286 at the PAS of AChE resulting in improved inhibitory activity. Addition of thiophene groups at both R1 and R2 led to a slight increase in AChE activity compared to JWS however to a lesser degree than the corresponding phenyl substitutions. None of the pyridazine substitutions however, provide improvements in antagonist activity for the muscarinic M2 receptor relative to the JWS parent compound. Respectable levels of activity were observed however for compounds 5, 7 and 10. The higher levels of M2 activity are favored by a methyl group at R1 or R2 as seen in these compounds. Generally speaking, a bulky substituent at R1 leads to decreased potency on M2. Interestingly the presence of two phenyl substituents led to increased M3 activity and slightly decreased M2 activity (compare 12 vs 10). In order to assess the further potential of these compounds as AD therapeutics, blood brain barrier penetration prediction was undertaken for each of the lead series. Of the most active compounds in Table 1, JWS and compound 10 were both predicted to have good BBB permeability (AdaBoost_MACCSFP BBB score of 0.558 and 0.934, respectively; See the Supplementary information for more details).

Scheme 1.

Table 1.

Structure–activity relationship for JWS analogs containing a modified 4-nitropyridazine on targets relevant to neurocognitive disorders

Table 3.

JWS analogs containing cyclic imide groups

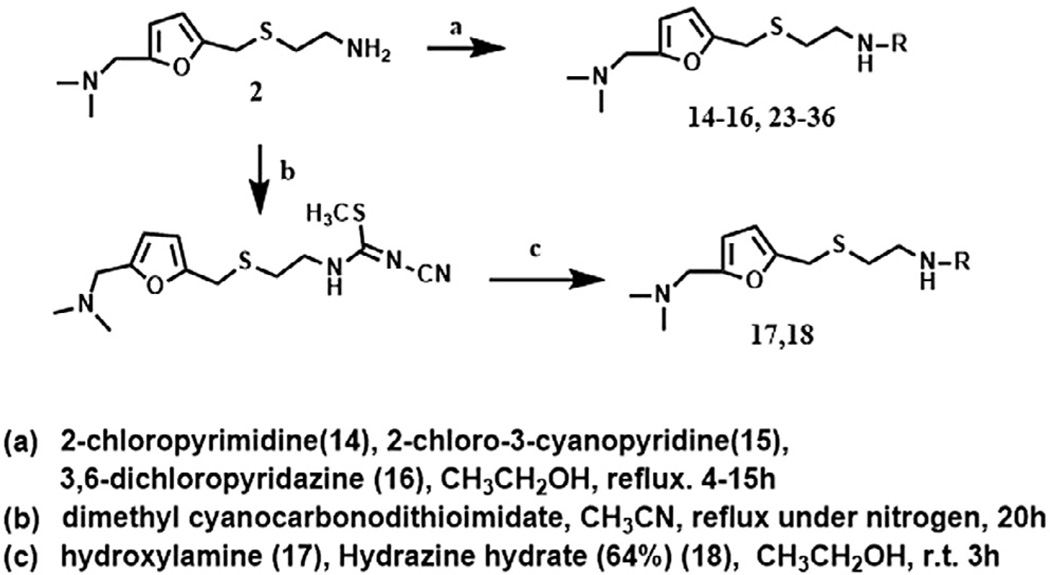

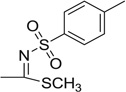

Synthesis and evaluation of JWS analogs containing pyridazine isosteres

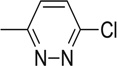

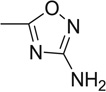

An interesting observation from this study was that 4-nitropyridazine analogs, including JWS, undergo a degree of chemical decomposition (estimated at about 10% after 6 months) as evidenced by the appearance of a new 1H NMR peak and a color change. Further analysis using HPLC-MS and followed by NMR, determined the primary impurity to be the product of replacement of the nitro with a hydroxyl group. Pharmacological testing of the purified hydroxyl compound revealed no AChE or M2 antagonist activities and therefore, nitropyridazine derivatives were tested for other activities immediately following synthesis. This observation led to the synthesis of compounds 14–18 (Scheme 2) which incorporate pyridazine isosteres in order to improve chemical stability. As shown in Table 2, the AChE inhibitory activities of compound 14–18 decreased (IC50 >5 µM) compared to the activity of JWS, suggesting that the nitropyridazine group is a critical binding determinant. Compound 16 (chloropyridazine) possessed an IC50 value of 10.41 µM for AChE, which is similar to that of the pyrimidine containing compound 14. These results indicate that functional groups with hydrogen bond acceptors might be favorable for effective AChE inhibitory activity since the nitro group appears to be a critical determinant. This prediction was further corroborated by docking results (Fig. 3 left panel). One of the oxygen atoms in the NO2 group interacts with Arg296 via a hydrogen bond contributing to its ligand-enzyme binding at the PAS of AChE. Therefore, compounds 19–26 with different hydrogen bond acceptor groups were synthesized using routes described in Schemes 2 and 3.

Scheme 2.

Table 2.

JWS analogs with different aromatic groups and their multiple activities

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | AChE (IC50 µM) | BuChE (IC50 µM) | M1(%)a | M2(%) | M3(%) | M4(%) |

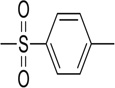

| 14 |  |

16.18 | 7.65 | 56.2 | 50.8 | 24.3 | 24.9 |

| 15 |  |

5.34 | 8.36 | n.t. | n.t. | n.t. | n.t. |

| 16 |  |

10.41 | >50 | 25.2 | 9.8 | 2.3 | 7.7 |

| 17 |  |

>50 | >50 | 69.9 | 72.8 | 49.8 | 42.7 |

| 18 |  |

>50 | >50 | 57.4 | 71.3 | 30.1 | 43.6 |

| 19 |  |

4.04 | 21.18 | 72.1 | 54 | 41.5 | 47.7 |

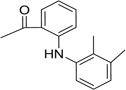

| 20 |  |

1.18 | 2.96 | 88.5 | 67 | 66.6 | 62.3 |

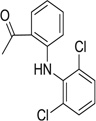

| 21 |  |

1.65 | 7.1 | 88.8 | 81 | 90.4 | 92.1 |

| 22 |  |

>50 | >50 | 37.5 | −19 | 18.5 | 4.2 |

| 23 |  |

>50 | 47.21 | n.t. | n.t. | n.t. | n.t. |

| 24 |  |

>50 | >50 | n.t. | n.t. | n.t. | n.t. |

| 25 |  |

>50 | >50 | 77.4 | 50.8 | 69.6 | 33.8 |

| 26 |  |

5.01 | 7.65 | 60.1 | 27.4 | 43.5 | 47.3 |

Muscarinic receptor activities are the percentage of binding inhibition.

Figure 3.

Left Panel: The interactions of the 4-nitropyridazine group of JWS showing the hydrogen bond interaction of the critical nitro group. Right Panel: The binding mode of the 1,8-napthamimide derivative 33 illustrating the pi-pi interactions with Trp 286 and the hydrogen bonds of the nitro group.

Scheme 3.

The resulting structural modifications of the JWS parent led to more stable chemical entities and produced varying effects on AChE inhibition. Of this series, compounds 19–21 had the highest levels of AChE inhibition as indicated by low micromolar IC50 values. These derivatives all contain a nitro group again pointing to its critical role in binding to the PAS. A significant observation resulted from the testing of compounds 20 and 21 which possessed respectable M1–M4 activity and in particular 21 had almost complete inhibition of all of these at 1 µM. This demonstrated that compound 21 would be a useful tool compound for probing the effects of inhibiting M1–M4 and AChE simultaneously. Compound 20, the most potent AChE inhibitor was not predicted to have efficient penetration of the BBB however (AdaBoost_MACCSFP BBB score of −3.906).

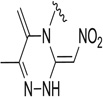

Synthesis and evaluation of JWS analogs containing cyclic imide isosteres

Further to the synthesis and testing of the pyridazine isosteres shown in Table 2, a series of cyclic imide groups were incorporated onto the amine of compound 2 (Scheme 3, Table 3). These include N-substituted succinimides (27, 28), phthalimides (one phenyl ring; 29, 30, 31), and also 1,8-naphthalimides (two fused phenyl rings; 31, 32). There is a general trend among these analogs for potency enhancement as the size of the pyrimidine replacement increases. The succinimide analogs are 5 to 10 fold less potent than the larger phthalimides with the 4-nitro (30) and the unsubstituted (29) phthalimides being the most active with low micromolar IC50 s. The 5-nitro (31) however was considerably less active having a 46 µM inhibition constant. As mentioned above, the 1,8-naphthalimides were the most potent of the cyclic imide series with the 3-nitro derivative, 33 delivering the most effective AChE inhibition (IC50 = 0.15 µM) while also possessing good levels of BuChE inhibition (IC50 = 8.01 µM). Surprisingly none of the analogs had activity for the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (data not shown). According to its predicted AChE binding mode (Fig. 3, right panel), the 3-nitro-1,8-naphthalimide group binds to the PAS through various interactions including two hydrogen bonds, (NO2 interaction with Tyr72 and one of the imide carbonyl groups has contacts with Arg296) while the napthyl ring system provides π–π stacking interactions with Trp286.

The model structures generated through docking indicate that these structural characteristics contribute to the potent AChE inhibitory activity and moderate BuChE inhibition of the naphthalimide series and as before an aromatic nitro group is a key binding determinant. Compared to donepezil (IC50 = 0.050 µM), compound 33 is only 3 fold less active and is the most potent compound in the entire series of JWS analogues. While these compounds possess improved AChE inhibitory activities, the naphthalimide modification results in diminished binding affinities for M1–M4 receptors compared to JWS. These results also indicate that while the 5,6 position on the 4-nitropyridazine moiety of JWS may not be necessary for AChE inhibition, it is a critical determinant for potent and selective binding to the M2 receptor. For the analogs investigated in this study it was observed that the BuChE inhibitory activity is considerably less sensitive to structural modification and that compounds generally had micromolar IC50 values. Compound 33, again the most potent AChE inhibitor in this series was predicted to have excellent penetration of the BBB (AdaBoost_MACCSFP BBB score of 5.498) thereby suggesting its potential as an anti-AD therapeutic.

In summary, through molecular modeling and rationally designed structural modifications, the multi-target structure–activity relationship for a series of ranitidine analogs has been explored. Of particular note, replacement of the 4-nitropyridazine moiety with cyclic imido groups resulted in stable chemical entities while retaining high efficacy as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Furthermore, docking studies suggest that optimization of the aromatic moiety results in greater complementarity of the hydrophobic and π–π interactions with the PAS of AChE and where the SAR of the imide series demonstrates that inhibition is increased by the addition of aromatic rings to the cyclic imide portion of the structure. While improving AChE activity, these structural modifications diminished the binding affinities and selectivities for M1–M4 receptors compared to JWS although progress was made in obtaining compounds with varying individual profiles for the individual muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. These results suggest that while the 4-nitropyridazine moiety of JWS is important for AChE inhibition, it is critical for potent and selective M2 receptor antagonism. This study also identified the 3-nitro-1,8-naphthalimide derivative (33) as providing the most potent inhibition and representing an effective structural scaffold for AChE and BuChE antagonists. The further potential of compound 33 as an AD therapeutic was demonstrated by its significant improvement in predicted BBB permeability over JWS and other compounds from the first two series (Tables 1 and 2). Thus compound 33 and similar 1,8-naphthalimide derivatives warrant further investigation and to this end, further structural and synthetic efforts can be directed to improve the M2 receptor affinity of the cyclic imide series as an effective approach to generate potential MTDL’s for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Michael Walla and William Cotham in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of South Carolina for assistance with Mass Spectrometry and Helga Cohen and Dr. Perry Pellechia for NMR spectrometry. We thank Dr. Jelveh Lameh for providing cell lines expressing muscarinic receptors. This work was supported by the NIH grant RO1DA035714.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data (full synthetic procedures used, characterization data for compounds made and further details on the computational experiments that were carried out) associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.09.072.

References and notes

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2011 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry E, Walker M, Grace J, Perry R. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:273. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_standard_prescriptions.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JH, Jeong SK, Kim BC, Park KW, Dash A. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2015;131:259. doi: 10.1111/ane.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terry AV, Jr, Buccafusco JJ. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;306:821. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.041616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buccafusco JJ, Terry AV., Jr J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;295:438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry EK, Perry RH, Blessed G, Tomlinson BE. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1978;4:273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1978.tb00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greig NH, Utsuki T, Ingram DK, Wang Y, Pepeu G, Scali C, Yu QS, Mamczarz J, Holloway HW, Giordano T, Chen D, Furukawa K, Sambamurti K, Brossi A, Lahiri DK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:17213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508575102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mash DC, Flynn DD, Potter LT. Science. 1985;228:1115. doi: 10.1126/science.3992249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quirion R. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 1993;18:226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seguela P, Wadiche J, Dineley-Miller K, Dani JA, Patrick JW. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00596.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bencherif M, Lippiello PM. Med. Hypotheses. 2010;74:281. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puzzo D, Gulisano W, Arancio O, Palmeri A. Neuroscience. 2015;307:26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Osta A, Alberini CM. Learn Mem. 2009;16:267. doi: 10.1101/lm.1310209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inestrosa NC, Alvarez A, Calderon F. Mol. Psychiatry. 1996;1:359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartolini M, Bertucci C, Cavrini V, Andrisano V. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;65:407. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.del Monte-Millan M, Garcia-Palomero E, Valenzuela R, Usan P, de Austria C, Munoz-Ruiz P, Rubio L, Dorronsoro I, Martinez A, Medina MJ. Mol. Neurosci. 2006;30:85. doi: 10.1385/JMN:30:1:85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darvesh S, Hopkins DA, Geula C. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;4:131. doi: 10.1038/nrn1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai MK, Lai OF, Keene J, Esiri MM, Francis PT, Hope T, Chen CP. Neurology. 2001;57:805. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sweet RA, Nimgaonkar VL, Devlin B, Jeste DV. Mol. Psychiatry. 2003;8:383. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thal DM, Sun B, Feng D, Nawaratne V, Leach K, Felder CC, Bures MG, Evans DA, Weis WI, Bachhawat P, Kobilka TS, Sexton PM, Kobilka BK, Christopoulos A. Nature. 2016;531:335. doi: 10.1038/nature17188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavalli A, Bolognesi ML, Minarini A, Rosini M, Tumiatti V, Recanatini M, Melchiorre C. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:347. doi: 10.1021/jm7009364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolognesi ML, Rosini M, Andrisano V, Bartolini M, Minarini A, Tumiatti V, Melchiorre C. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009;15:601. doi: 10.2174/138161209787315585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valli MJ, Tang Y, Kosh JW, Chapman JM, Jr, Sowell JW., Sr J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:3141. doi: 10.1021/jm00095a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terry AV, Jr, Buccafusco JJ, Herman EJ, Callahan PM, Beck WD, Warner S, Vandenhuerk L, Bouchard K, Schwarz GM, Gao J, Chapman JM. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011;336:751. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.175422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terry AV, Jr, Gattu M, Buccafusco JJ, Sowell JW, Sr, Kosh JW. Drug Dev. Res. 1999;47:97. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bourne Y, Radic Z, Sulzenbacher G, Kim E, Taylor P, Marchot P. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:29256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Jr, Feather-Stone RM. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961;7:88. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu J, Taniguchi T, Konishi Y, Mayumi M, Muramatsu I. Life Sci. 1998;62:1089. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu J, Takita M, Konishi Y, Sudo M, Muramatsu I. Brain Res. 1996;732:257. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00704-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.