Abstract

Acute nausea and vomiting are often self-limited or easily treated. Persistent vomiting, however, poses diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for the primary care physician. In addition to gastrointestinal, neurologic, and endocrine disorders, the differential diagnosis includes psychiatric illnesses, such as eating and factitious disorders.

We present the case of a 52-year-old woman referred to the Tulane University Internal Medicine/Psychiatry clinic with persistent daily vomiting for 8 years despite repeated medical evaluations. The vomiting was of sufficient severity to require intensive care unit admission for hematemesis. A dually trained internal medicine-psychiatry house officer obtained further history and identified that the woman experienced an intrusive thought that urged her to vomit after each meal. Resisting the urge resulted in intolerable anxiety that was relieved only by vomiting. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) was diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria. Initiation of escitalopram with titration to clinical response resulted in full symptom resolution and meaningful quality of life improvement.

Pertinent literature was reviewed using 2 methods: (1) an English-language MEDLINE search (1966–February 2004) using the search terms vomiting and (chronic or psychogenic or psychiatric), and obsessive-compulsive disorder and (primary care or treatment); and (2) a direct search of reference lists of pertinent journal articles.

A review of psychiatric etiologies of vomiting and primary care aspects of OCD is presented. Primary care clinicians are strongly encouraged to consider psychiatric etiologies, including OCD, when common symptoms persist or present in atypical ways. Such disorders can be debilitating but also responsive to treatment.

Acute episodes of nausea and vomiting are common clinical complaints seen in the primary care setting.1 Fortunately, most episodes are self-limited, especially those caused by infectious agents.2 In some patients, vomiting persists. The incidence of persistent vomiting is difficult to estimate, due in part to the lack of a unique ICD-9 code. When present, persistent vomiting contributes to significantly diminished quality of life and poses diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for the clinician.

When common symptoms present in an atypical manner or persist, a shift in diagnostic approach and a consideration of psychiatric or psychosocial etiologies are often required. We present the case of a 52-year-old woman with 8 years of persistent vomiting caused by unrecognized obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The delay in her diagnosis resulted in diminished quality of life and severe medical complications. Once diagnosed and appropriately treated, she reported symptomatic relief for the first time in nearly a decade. We will review the differential diagnosis of vomiting due to psychiatric disorders and provide a review of OCD.

CASE

Ms. A is a 52-year-old woman who was referred to the Tulane University Internal Medicine/Psychiatry (Med/Psych) clinic, an academic primary care residency training clinic that serves a low socioeconomic inner-city population, for evaluation of persistent vomiting. During her initial medical/psychiatric consultation, Ms. A reported daily vomiting that began in the early 1990s and continued for the next 8 years. Approximately 2 hours after each meal, she experienced an abdominal “fullness” followed by vomiting. She denied associated nausea or abdominal pain. The vomiting had twice been of sufficient severity to require intensive care unit admission for hematemesis. During one of the admissions, the patient required the transfusion of 8 units of packed red blood cells, and esophagoduodenoscopy demonstrated a Mallory-Weiss tear and a hiatal hernia. Repeated abdominal ultrasounds performed during previous work-ups had demonstrated gallstones without dilatation of the biliary system. Previous trials of proton pump inhibitors and H2-blockers had failed to provide relief. Ms. A also had notably refused a previously offered cholecystectomy and surgical repair of the hiatal hernia.

The medical and psychiatric review of symptoms revealed that Ms. A experienced an intrusive thought urging her to induce vomiting after eating. She described this thought as “crazy,” stating, “I know the problem is up here” as she pointed to her head. Resisting the urge to vomit provoked escalating and eventually intolerable levels of anxiety relieved only by vomiting. In a ritualistic manner, she drank 2 glasses of water before vomiting in an attempt to protect her esophagus and stomach. Reflecting on prior hospitalizations, she was fully aware that she might die from further medical complications and was tormented by her inability to stop vomiting. Her distress during the past year was so profound that she had contemplated suicide. She denied guilt after vomiting, did not intend to lose weight, and was satisfied with her body habitus. She denied other obsessions, compulsions, delusions, and current depressive symptoms.

The past medical history included hypertension, gastrointestinal reflux disease, and, per the medical records, a remote history of pancreatitis. Past surgical history included a bilateral oophorectomy and partial hysterectomy for symptomatic fibroids 20 years ago. Her past psychiatric history was notable for diagnoses of depression and panic disorder for which paroxetine, 20 mg daily had been prescribed 3 years prior to her presentation to the Med/Psych clinic. She remained on paroxetine therapy for less than 1 year, and there was documentation of mild clinical improvement in the depressive symptoms during the interval when she was taking paroxetine. The vomiting persisted. For the subsequent 2 years, she was not receiving an antidepressant. In response to the patient's complaint of “nervous seizures,” her family physician prescribed gabapentin 4 months prior to her presentation to the Med/Psych clinic. Two months after Ms. A started gabapentin, these “nervous seizures” were diagnosed as panic attacks by the referring psychiatry-neurology house officer, who prescribed escitalopram and clonazepam. Gabapentin was continued since it seemed to have a modest impact on the symptoms. Once the new agents were initiated, the panic attacks diminished markedly in severity and frequency. Her active medications included escitalopram, 10 mg daily; clonazepam, 0.5 mg every 12 hours; gabapentin, 300 mg 3 times daily; and diltiazem, 240 mg daily.

Ms. A had significant psychosocial stressors. She was living with a man who regularly smoked crack cocaine and was emotionally abusive. She had been employed as a certified nursing assistant for a home health agency, but was unable to work due to agoraphobia and subsequently experienced financial difficulties. In spite of a history of problem drinking, she denied drinking currently and denied illicit drug use.

The findings on physical examination were unremarkable except for a weight of 82 kg. Her abdomen was protuberant, soft, and nontender, with audible bowel sounds. Hepatosplenomegaly was not appreciated, and no masses were palpated. Digital rectal examination was not performed. On mental status examination, she was pleasant and well-groomed and established good rapport with the interviewer. She was noticeably nervous during the interview. Her thought process was linear and goal-directed. She was fully oriented, demonstrated no evidence of psychosis, and denied suicidal or homicidal ideation.

Previous laboratory investigations demonstrated normal complete blood counts and serum amylase and lipase levels, as well as normal results for basic metabolic panels, liver function tests, and urinalyses.

The patient was diagnosed with OCD according to DSM-IV criteria. She was still engaging in daily vomiting at the time of consultation, yet the intensity of the obsessive thought had decreased on the current escitalopram dosage. She was encouraged to titrate the dosage to 20 mg daily and to return in 3 months. She presented for follow-up approximately 1 year later (December 2003), though she had been examined by the referring physician several times during that time period. Within 3 to 4 months after the escitalopram dosage was increased to 20 mg daily, she was asymptomatic for the first time in 8 years. She has remained asymptomatic. She has returned to work and reported a significant improvement in her quality of life.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Pertinent literature was reviewed by using 2 methods: (1) an English-language MEDLINE search (1966–February 2004) using the search terms vomiting and (chronic or psychogenic or psychiatric), and obsessive-compulsive disorder and (primary care or treatment); and (2) a direct search of reference lists of pertinent journal articles.

DISCUSSION

This case highlights the limitations of a routine diagnostic approach to persistent or unusual symptoms. Our patient had seen several physicians, yet the same diagnoses were revisited repeatedly. She underwent multiple procedures, and several were repeated despite normal findings, yet the causal diagnosis remained elusive and costs mounted. Her previous physicians considered many of the common gastrointestinal diseases that may present with persistent vomiting, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, pepticulcer disease, obstructing masses, gastroparesis, and cholecystitis. Neurologic, toxin-induced, and endocrine disorders might also have been considered. It is precisely in such perplexing patients that the consideration of a psychiatric etiology is most germane.

Psychiatric Etiologies of Persistent Vomiting

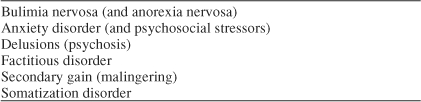

Several psychiatric syndromes have been associated with persistent vomiting (Table 1). Among these are major depression, adjustment disorders with anxious features, and social phobia.3,4 Though not classically psychiatric, conditioning can also contribute to such symptoms. An example is anticipatory nausea and vomiting found in patients who vomit with chemotherapy. In these individuals, nausea, vomiting, and anxiety subsequently occur in medical settings or in the presence of medical implements.5

Table 1.

A Differential Diagnosis of Persistent Vomiting Due to Psychiatric Illness

Bulimia nervosa (BN) may involve self-induced vomiting, typically in normal-weight to overweight persons. Bulimia nervosa is characterized by recurrent binge eating with a sense of loss of control. Persons with BN may engage in compensatory behaviors other than vomiting, such as restriction of food intake, excessive exercise, and misuse of diuretics, laxatives, enemas, and other medications.6 There is often a sense of guilt after purging. Anorexia nervosa (AN) may present as a binge eating and purging type. Diagnostic criteria for AN include a refusal to maintain greater than 85% of expected ideal body weight and an intense fear of gaining weight.6 The hallmarks of both disorders are a preoccupation with weight and a self-evaluation significantly influenced by body shape.6

Individuals with factitious disorders, e.g., Munchausen's syndrome, engage in self-injurious behavior driven by an unconscious need to assume the sick role. These patients complain of illness to attract clinical attention, but do not divulge that the illness is self-induced. Collateral information from family or previous health care providers is invaluable. Observing behaviors such as enjoyment of hospitalization or invasive procedures can also be diagnostically useful.

People who are malingering, on the other hand, are consciously aware they are feigning or inducing illness for secondary gain. Examples of secondary gain include financial incentives or evasion of legal prosecution. In both cases, the patient may be inducing vomiting with an agent such as ipecac syrup. The behavior manifested by factitious disorder and malingering is similar, but the motivation for the behavior differs.

Schizophrenia and psychotic disorders may also present with vomiting or other gastrointestinal symptoms due to visceral hallucinations or stemming from ingestions related to a delusional system. Relevant cases from the authors' experience include a patient who repeatedly ingested toothbrushes and another who repeatedly attempted to pull evil spirits from his mouth in response to visual hallucinations and delusions. It is conceivable that such patients could present with gastrointestinal symptoms.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

OCD can present with somatic symptoms, including persistent vomiting, as illustrated in this case. First described within the psychiatric literature in 1838, OCD is characterized by recurrent obsessions (intrusive and inappropriate ideas, thoughts, or impulses) or compulsions (repetitive and intentional behaviors performed in response to obsessions or rigidly applied rules) that are severe enough to cause significant anxiety, distress, or impairment.6 The individual with OCD is aware that the obsessive thought is a product of his or her own mind. Patients may become extremely disabled as their days are consumed by completing compulsive rituals. Some of the more common compulsions include cleaning or washing, checking, and counting rituals. OCD was once thought to be rare, but recent data estimate it to be the fourth most common psychiatric disorder, with a lifetime prevalence of 2% to 3% in the general population.7 There is also frequent comorbidity with other psychiatric diagnoses, including eating disorders. OCD patients have an 8% to 12% risk of developing eating disorders versus the risk to the general population of 1% for anorexia nervosa and 4% for bulimia.8

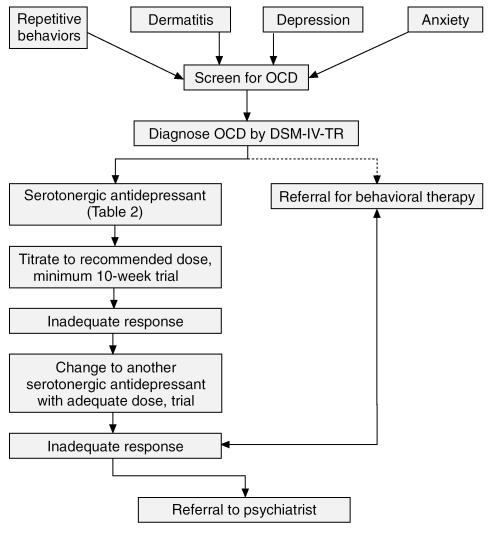

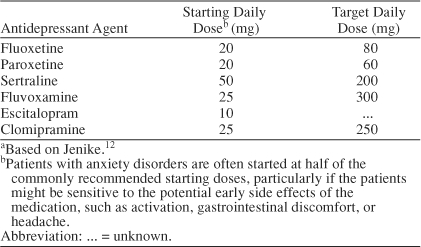

Primary care clinicians are well poised to diagnose OCD and initiate therapy. Despite the relatively high prevalence of the disorder, however, the diagnosis is frequently unrecognized.9 Patients' reluctance to seek help due to embarrassment and shame, the mercurial presentation of OCD, and comorbidity can complicate the establishment of the diagnosis. A proposed treatment algorithm is provided (Figure 1). Serotonergic antidepressants are the first-line pharmacologic treatment for OCD, with the addition of behavioral therapy when available. As illustrated in this case, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) target dosages for treatment of OCD are typically higher than those used in the treatment of depression (Table 2), and clinical response may take several weeks.

Figure 1.

Proposed Algorithm for Primary Care Management of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Table 2.

Recommended Daily Starting and Target Dosages of Serotonergic Medications for Obsessive-Compulsive Disordera

Somatoform Variants of OCD

Patients with OCD or obsessive-spectrum disorders may present in the primary care setting with somatic manifestation of their disorder. Chapped hands or dermatitis from excessive hand washing, gum lesions from excessive teeth cleaning, or dermatologic lesions from repetitive scratching and skin picking should serve as red flags for possible OCD.10 Other possible somatic presentations include abdominal discomfort and constipation from obsessive fear of having a bowel movement11 and alopecia from the obsessive-spectrum disorder trichotillomania.

CONCLUSION

This article describes the presentation of a woman with life-threatening recurrent vomiting due to unrecognized OCD. Treatment with an SSRI at an appropriate dosage resulted in complete resolution of her symptoms. Primary care clinicians are encouraged to consider psychiatric etiologies of persistent vomiting or other persistent complaints. Treatment is targeted toward the underlying disorder. Treatment options for OCD include serotonergic agents and behavioral therapy. Referral to mental health services can be made if there is minimal or no response to appropriate and adequate pharmacologic treatment.

Drug names: clomipramine (Anafranil and others), clonazepam (Klonopin and others), diltiazem (Taztia, Cartia, and others), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), gabapentin (Neurontin and others), paroxetine (Paxil and others), sertraline (Zoloft).

Footnotes

Presented as a poster at the southern regional meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, February 13, 2004, New Orleans, La.

The authors report no financial affiliation or other relationship relevant to the subject matter of this article.

REFERENCES

- Cherry DK, Burt CW, and Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2001 summary. Adv Data. 2003 1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller RC.. ABC of the upper gastrointestinal tract: anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and pain. BMJ. 2001;323:1354–1357. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7325.1354.0959-8138(2001)323<1354:AOTUGT>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraoka M, Mine K, and Matsumoto K. et al. Psychogenic vomiting: the relation between patterns of vomiting and psychiatric diagnoses. Gut. 1990 31:526–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stravynski A.. Behavioral treatment of psychogenic vomiting in the context of social phobia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1983;171:448–451. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198307000-00010.0022-3018(1983)171<0448:BTOPVI>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrykowski M.. The role of anxiety in the development of anticipatory nausea in cancer chemotherapy: a review and synthesis. Psychosom Med. 1990;52:458–475. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199007000-00008.0033-3174(1990)052<0458:TROAIT>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL.. The epidemiology and clinical features of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1992;15:743–758.0193-953X(1992)015<0743:TEACFO>2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy TA, Osacar A, Marks I.. History of eating disorders in female patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 1993;14:439–443. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199312)14:4<439::aid-eat2260140407>3.0.co;2-6.0276-3478(1993)014<0439:HOEDIF>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander E, Kwon J, and Stein DJ. et al. Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders: overview and quality of life issues. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996 57(suppl 8):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch M, Paradis C, and Friedman S. et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in patients with chronic pruritic conditions: case studies and discussion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 26:549–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan H, Sadock B. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Jenike MA.. Clinical practice: obsessive-compulsive disorder. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:259–265. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp031002.0028-4793(2004)350<0259:CPOD>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]