Abstract

Gastric adenocarcinoma of the fundic gland (chief cell-predominant type, GA-FG-CCP) is a rare variant of well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, and has been proposed to be a novel disease entity. GA-FG-CCP originates from the gastric mucosa of the fundic gland region without chronic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia. The majority of GA-FG-CCPs exhibit either a submucosal tumor-like superficial elevated shape or a flat shape on macroscopic examination. Narrow-band imaging with endoscopic magnification may reveal a regular or an irregular microvascular pattern, depending on the degree of tumor exposure to the mucosal surface. Pathological analysis of GA-FG-CCPs is characterized by a high frequency of submucosal invasion, rare occurrences of lymphatic and venous invasion, and low-grade malignancy. Detection of diffuse positivity for pepsinogen-I by immunohistochemistry is specific for GA-FG-CCP. Careful endoscopic examination and detailed pathological evaluation are essential for early and accurate diagnosis of GA-FG-CCP. Nearly all GA-FG-CCPs are treated by endoscopic resection due to their small tumor size and low risk of recurrence or metastasis.

Keywords: Narrow-band imaging, Pepsinogen-I, Fundic gland, Gastric adenocarcinoma, Chief cell

Core tip: Gastric adenocarcinoma of the fundic gland (chief cell-predominant type, GA-FG-CCP) was recently proposed as a novel disease entity. The endoscopic and clinicopathological characteristics of GA-FG-CCP are distinct from those of gastric adenocarcinomas with an intestinal phenotype that originate from the mucosa with chronic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia. Careful endoscopic examination and detailed pathological evaluation are essential for early and accurate diagnosis of GA-FG-CCP.

INTRODUCTION

It had been thought that differentiated adenocarcinomas which originate from the intestinal metaplasia involving Helicobactor pylori (H. pylori) infection have an intestinal phenotype, whereas undifferentiated adenocarcinomas which originate from the gastric mucosa without the process of intestinal metaplasia have a gastric phenotype[1]. However, progress in immunohistochemistry has revealed that some differentiated adenocarcinomas have a gastric phenotype[2].

In 2006, Yao et al[3] described extremely well-differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma with a gastric phenotype similar to gastric foveolar epithelium, mucous neck cells and pyloric glands. Thereafter, the first case of gastric adenocarcinoma with differentiation into chief cells within the fundic gland by Tsukamoto et al[4]. Furthermore, 10 cases of gastric adenocarcinoma with differentiation into chief cells were documented by Ueyama et al[5] who proposed a novel disease concept: gastric adenocarcinoma of the fundic gland (chief cell-predominant type, GA-FG-CCP) based on the characteristic morphology and immunohistochemistry. Because GA-FG-CCPs are thought to originate from gastric mucosa of the fundic gland region without chronic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia, it is expected that the proportion of gastric adenocarcinomas diagnosed as GA-FG-CCP will increase in parallel with the declining frequency of H. pylori infection.

GA-FG-CCP is defined as a neoplastic lesion, which is composed of cells that resemble the fundic gland cells and is positive for pepsinogen-I: a marker of chief cells on immunohistochemistry[5]. For early and precise diagnosis, it is vital to undertake careful endoscopic examination and detailed pathological evaluation using immunohistochemistry. In particular, endoscopists should be able to reliably detect a suspicious lesion that may be a GA-FG-CCP during screening. As the concept of GA-FG-CCP as an individual disease entity has become better established, information concerning the pathological features of GA-FG-CCP has occasionally been published. Moreover, several detailed endoscopic investigations of GA-FG-CCP have recently become available. Here, the unique endoscopic and clinicopathological features of GA-FG-CCP will be discussed.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

GA-FG-CCP is a very rare variant of gastric adenocarcinoma. A review of studies on GA-FG-CCP published in English language indicates that 46 cases have been reported to date[4-16]. Almost all patients were Japanese, but a study by Singhi et al[9] in 2012 comprised 10 non-Asian patients, including Hispanics, Caucasians and African-Americans. The clinical characteristics of the 46 previously reported cases are presented in Table 1. According to Ueyama et al[12], GA-FG-CCP was detected in only 10 of 14080 patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Park et al[8] identified GA-FG-CCP in only 3 of over 6000 Korean patients with gastric adenocarcinomas resected by endoscopy or surgery. During the 3 years after 2010 when the concept of GA-FG-CCP was first proposed, Miyazawa et al[13] reported that GA-FG-CCP accounted for 0.98% of early gastric adenocarcinomas treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). Among Japanese cases of GA-FG-CCP, the male-to-female ratio is approximately 1.4, which is lower than that of the estimated morbidity from all gastric adenocarcinomas in 2011 in Japan (2.1)[17]. The average age of Japanese patients is 67.7 years, with a range of 42 to 82 years. Early cases of GA-FG-CCP generally have no or mild subjective symptoms, although Singhi et al[9] found that all 10 cases had clinical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux, suggesting that gastric acid secretion was maintained due to a lack of mucosal atrophy. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, none of the previous cases of GA-FG-CCP had evidence of H. pylori infection.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of previously reported cases

| Author (yr) | Number of patients | Sex (M:F) | Age (yr, average) | Race or nationality | Clinical symptoms | Therapeutic method | Survival time (mo, average) | Outcome |

| Tsukamoto et al[4] (2007) | 1 | F | 82 | Japanese | No symptom | EMR | ND | ND |

| Ueyama et al[5] (2010) | 10 | 6:4 | 65.5 (42-79) | Japanese: 10 | ND | EMR: 2 | 37.1 (10-70) | Alive, NED: 10 |

| ESD: 5 | ||||||||

| Operation: 3 | ||||||||

| Fukatsu et al[6] (2011) | 1 | M | 56 | Japanese | No symptom | EAM | 12 | Alive, NED |

| Terada et al[7] (2011) | 1 | M | 78 | Japanese | Abdominal pain (colon cancer) | No therapy (only biopsy) | 3 | Died (colon cancer) |

| Park et al[8] (2012) | 3 | 3:0 | 65.3 (47-76) | Korean: 3 | ND | ESD: 1 | 24.3 (11-32) | Alive, NED: 3 |

| Operation: 1 | ||||||||

| Operation after ESD: 1 | ||||||||

| Singhi et al[9] (2012) | 10 | 4:6 | 64.2 (44-79) | Hispanic: 4 | GERD: 10 | polypectomy: 10 | 15.4 (6-39) | Alive, NED: 8 |

| Caucasian: 2 | Alive, persistence: 1 ND: 1 | |||||||

| African American: 2 | ||||||||

| Chinese: 1 | ||||||||

| Unknown: 1 | ||||||||

| Chen et al[10] (2012) | 1 | M | 79 | Caucasian | GERD | EMR | 2 | Alive, NED |

| Esophageal stricture | ||||||||

| Abe et al[11] (2013) | 1 | F | 71 | Japanese | No symptom | EMR | 12 | Alive, NED |

| Ueyama et al[12] (2014) | 10 | 6:4 | 66.5 (55-78) | Japanese: 10 | ND | EMR: 2 | 13.2 (1-19) | Alive, NED: 10 |

| ESD: 8 | ||||||||

| Miyazawa et al[13] (2015) | 5 | 3:2 | 72.2 (67-78) | Japanese: 5 | No symptom: 5 | ESD: 4 | 19.4 (10-28) | Alive, NED: 5 |

| Operation after ESD: 1 | ||||||||

| Parikh et al[14] (2015) | 1 | M | 66 | Caucasian | Heartburn (GERD) | EMR | ND | Alive, NED |

| Kato et al[15] (2015) | 1 | M | 80s | Japanese | ND | CLEAN-NET | 3 | Alive, NED |

| Fujii et al[16] (2015) | 1 | F | 64 | Japanese | ND | ESD | ND | ND |

CLEAN-NET: Combination of laparoscopic and endoscopic approaches to neoplasia with non-exposure technique; EAM: Endoscopic aspiration mucosectomy; EMR: Endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; F: Female; M: Male; GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease; NED: No evidence of disease; ND: Not described.

ENDOSCOPIC FINDINGS

Endoscopic findings from patients with GA-FG-CCP are shown in Figure 1. The endoscopic characteristics of 46 previously reported cases are summarized in Table 2. GA-FG-CCP was located in the upper third of the stomach in 87% of cases. The average tumor diameter was 7.5 mm, and approximately 80% of all tumors were less than 10 mm in diameter at the time of diagnosis. Macroscopically, about three-quarters of GA-FG-CCPs were recognized by an elevated shape, especially a submucosal tumor (SMT)-like shape, while the other one-quarter had a flat or depressed shape. GA-FG-CCP with an SMT-like elevated shape has a poorly demarcated border and softness[12]. Miyazawa et al[13] suggested that a possible reason for the macroscopic similarity to SMT is that GA-FG-CCP originates from deep layers of the gastric mucosa. GA-FG-CCP may be likely to grow vertically into the submucosa and develop laterally toward the surrounding tissue. If GA-FG-CCP grew in a straight direction towards the mucosal surface, it would be recognized as a superficial unsmooth tumor. Ueyama et al[12] speculated that surface mucosal epithelial cells are maintained because tumors barely destroy the surrounding tissue. GA-FG-CCP with a flat or depressed shape, which accounts for about 20% of all cases, appears to be more difficult to recognize than GA-FG-CCP with an SMT-like elevated shape. With respect to coloration, GA-FG-CCP is often covered with normal-colored or faded (i.e., whitish or yellowish) mucosa. Fujii et al[16] suggested that the faded appearance is caused by atrophy in the foveolar epithelium above cancer tubules, but not in the surrounding mucosa. Another characteristic of GA-FG-CCP is vasodilation on the tumor surface, which is attributed to the displacement of surface vessels by tumor tissue followed by congestion[13]. Branched vessels on the tumor surface were also thought to be present in the deep region of the mucosal layer[12]. Narrow-band imaging (NBI) may clarify the presence of vasodilatation and branched vessels on the tumor surface[12,13,16]. However, it has not been possible to pathologically confirm the above explanations for fine vessels.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic findings from representative GA-FG-CCP cases. A: White light endoscopy revealed a submucosal tumor-like elevated tumor with a whitish mucosal surface and dilatation of microvessels. The surrounding mucosa had no atrophic changes (left). Narrow-band imaging with magnification showed an absent microsurface pattern and irregular microvascular pattern on a small portion of the tumor (right); B: White light endoscopy revealed a submucosal tumor-like elevated tumor with normal-colored mucosal surface. The surrounding mucosa had no atrophic changes (left). Narrow-band imaging with magnification showed a regular microsurface pattern and microvascular pattern on the entire tumor surface (right).

Table 2.

Endoscopic characteristics of previously reported cases

| Author (yr) | Number of patients | Location (U:M:L) | Size (mm, average) | Macroscopic shape | Color tone | Vessel findings |

NBI with magnification |

|

| MSP | MVP | |||||||

| Tsukamoto et al[4] (2007) | 1 | U | 16 | Elevated | Normal | Vasodilation | ND | ND |

| Ueyama et al[5] (2010) | 10 | 10:0:0 | 8.6 (4-20) | Elevated: 5 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Depressed: 5 | ||||||||

| Fukatsu et al[6] (2011) | 1 | U | 5 | Elevated | Yellowish | ND | ND | ND |

| Terada et al[7] (2011) | 1 | U | 20 | Elevated | Reddish | Vasodilation | ND | ND |

| Park et al[8] (2012) | 3 | 1:1:1 | 2.6 (1.2-3.6) | Elevated and depressed: 3 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Singhi et al[9] (2012) | 10 | 10:0:0 | 4.3 (2-8) | Elevated: 10 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Chen et al[10] (2012) | 1 | U | 12 | Elevated | Whitish | Vasodilation | ND | ND |

| Abe et al[11] (2013) | 1 | U | ND | Elevated | Yellowish | ND | ND | ND |

| Ueyama et al[12] (2014) | 10 | 6:4:0 | 9.3 (3-31) | Elevated: 6 | Whitish: 8 | Vasodilation: 5 | ND | ND |

| Depressed: 3 | Reddish: 2 | Normal: 5 | ||||||

| Miyazawa et al[13] (2015) | 5 | 5:0:0 | 7.8 (5-13) | Elevated: 4 | Whitish: 3 | Vasodilation: 5 | Regular: 3 | Regular: 3 |

| Flat: 1 | Normal: 2 | Absent: 2 | Irregular: 2 | |||||

| Parikh et al[14] (2015) | 1 | U | 7 | Elevated | Reddish | Vasodilation | ND | ND |

| Kato et al[15] (2015) | 1 | U | 15 | Elevated | Whitish | Vasodilation | Regular | Regular |

| Fujii et al[16] (2015) | 1 | U | < 10 | Depressed | Whitish | Vasodilation | Absent | Irregular |

U: Upper third; M: Middle third; L: Lower third; NBI: Narrow-band imaging; MSP: Microsurface pattern; MVP: Microvascular pattern; ND: Not described.

There are few reports on magnifying endoscopy for GA-FG-CCP[13,16]. NBI with magnification is assessed using the worldwide standard diagnostic system, the VS (vessel plus surface) classification, as proposed by Yao et al[18]. The VS classification system incorporates three indices: (1) the demarcation line (DL), which is the border between the tumor and the surrounding mucosa; (2) the microsurface pattern (MSP), which is microstructural patterns on the tumor surface such as marginal crypt epithelium; and (3) the microvascular pattern (MVP), which is the pattern of vascular architecture on the tumor surface such as subepithelial capillary. Miyazawa et al[13] demonstrated that NBI with magnification enabled detection of the absence of MSPs, indicating a lack of microstructure, and irregular MVPs, indicating non-uniformity and heterogeneity of microvascular structures, depending on the degree of tumor exposure to the mucosal surface. In contrast, NBI with magnification indicated that some GA-FG-CCPs had normal MSP and MVP. The presence of the DL, and irregular MVP and MSP, which are specific features of early gastric adenocarcinoma, may not be found in GA-FG-CCP[16]. Because GA-FG-CCP is located in the deep mucosal layer and is not exposed on the surface, detection of abnormal inner microstructures is prevented by the thick mucosa[13]. Consequently, evaluation by magnifying endoscopy may be used to assist, but not to make an accurate diagnosis of GA-FG-CCP[16].

Despite the use of endoscopy, a definite diagnosis is provided by histopathology. If GA-FG-CCP is suspected by an endoscopist, a pathologist should perform immunohistochemical staining to confirm the diagnosis[13]. The biopsy may be needed for a lesion suggesting a submucosal or carcinoid tumor but resembling GA-FG-CCP in order to distinguish GA-FG-CCP from these tumors. It is crucial to obtain an adequate amount of tissue because the tumorous tissue of GA-FG-CCP is usually located in the deep mucosal layer.

HISTOPATHOLOGICAL FINDINGS

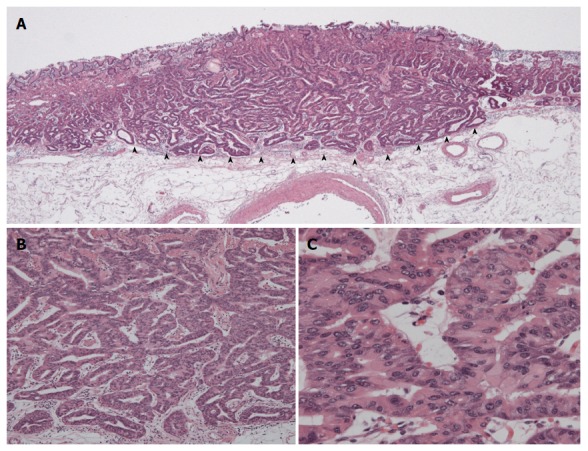

Histopathological findings from GA-FG-CCP cases are depicted in Figures 2 and 3. The histopathological characteristics of the 45 previously reported cases are shown in Table 3. GA-FG-CCP is a well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma composed of a variety of mildly atypical columnar cells that mimic the fundic glands[5]. The tumor originates from chief cells, which lies at the bottom of the fundic glands. A surface of tumor is primarily covered by non-atypical foveolar epithelium. Although the majority of tumors exhibit submucosal invasion, observations of lymphatic or venous invasion are rare[5,12,13]. With regard to biological behavior, GA-FG-CCPs are expected to be low-grade malignancies in view of their mild atypia. Due to the lack of recurrence or progression, Singhi et al[9] suggested that the term “GA-FG-CCP” is excessive, and the lesions should be considered as benign. As an alternative, the authors preferred the term “oxyntic gland polyp/adenoma” for GA-FG-CCP lesions. Although in some cases endoscopy revealed chronic atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia, tumors in most cases were surrounded by the gastric mucosa without pathological evidence of mucosal changes.

Figure 2.

Histopathological findings from a representative GA-FG-CCP case. A: In low-power view, the tumor arose from the deep layer of the lamina propria mucosa and invaded the submucosal layer (arrowhead). Most of the surface was covered with non-atypical foveolar epithelium; B and C: In high-power view, the tumor was composed of well-differentiated columnar cells mimicking the fundic gland cells with mild nuclear atypia.

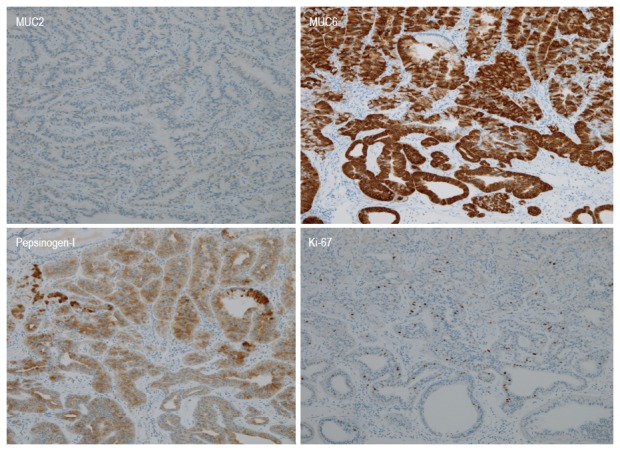

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical analysis of a representative GA-FG-CCP case. The tumor had diffuse positivity for MUC6 and pepsinogen-I, but was negative for MUC2 staining. The Ki-67 labeling index was very low.

Table 3.

Histopathological characteristics of previously reported cases

| Author (year) | Number of patients | Background mucosa | Depth (M:SM) (µm, average) | Lymphatic invasion (+:-) | Venous invasion (+:-) | MUC2 (+:-) | MUC5AC (+:-) | MUC6 (+:-) | CD10 (+:-) | Overexpression of p53 (+:-) | Ki-67 LI (%, average) |

| Tsukamoto et al[4] (2007) | 1 | ND | M | (-) | (-) | ND | ND | (+) | ND | ND | 7.9 |

| Ueyama et al[5] (2010) | 10 | Normal: 7 | 1:9 | 0:10 | 0:10 | 0:10 | 1:9 | 10:0 | 0:10 | 0:10 | 3.6 |

| Metaplasia: 1 | 844 (150 to 4000) | ||||||||||

| ND: 2 | |||||||||||

| Fukatsu et al[6] (2011) | 1 | ND | SM, 100 | (-) | (-) | ND | (-) | (+) | ND | ND | ND |

| Park et al[8] (2012) | 3 | Metaplasia: 2 | 1:2 | 0:3 | 0:3 | 0:3 | 3:0 | 3:0 | 0:3 | ND | ND |

| Gastritis: 1 | |||||||||||

| Singhi et al[9] (2012) | 10 | Normal: 7 | 10:0 | 0:10 | 0:10 | 0:3 | 0:10 | 10:0 | ND | 0:9 | 2.6 |

| Gastritis: 3 | ND: 1 | (0.2-10) | |||||||||

| Chen et al[10] (2012) | 1 | Normal | SM (Details unknown) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | 3.8 |

| Abe et al[11] (2013) | 1 | Normal | SM (Details unknown) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | 1.9 |

| Ueyama et al[12] (2014) | 10 | Normal: 9 | 5:5 | 1:9 | 0:10 | 0:10 | 4:6 | 10:0 | 2:8 | 0:10 | 8.6 (1-20) |

| Gastritis: 1 | 360 (100 to 1200) | ||||||||||

| Miyazawa et al[13] (2015) | 5 | Normal: 4 | 0:5 | 1:4 | 0:5 | 0:5 | 0:5 | 5:0 | ND | 0:5 | Very low: 5 (Details unknown) |

| Gastritis: 1 | 620 (80 to 1230) | ||||||||||

| Parikh et al[14] (2015) | 1 | ND | SM (Details unknown) | (-) | (-) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Kato et al[15] (2015) | 1 | Normal | SM, 300 | (-) | (-) | ND | ND | (+) | ND | ND | ND |

| Fujii et al[16] (2015) | 1 | Normal | SM, 300 | (-) | (-) | ND | (-) | (+) | ND | ND | ND |

LI: Labeling index; M: Mucosal; SM: Submucosal; ND: Not described.

Immunohistochemical analysis using the following biomarkers is important for the diagnosis of GA-FG-CCP: MUC5AC for foveolar cells; MUC6 for mucous neck cells or pyloric gland cells; MUC2 for goblet cells; CD10 for intestinal brush border cells; and pepsinogen-I for chief cells. Mucin phenotypes are assessed by the expression of gastric-type markers such as MUC5AC and MUC6, and intestinal-type markers such as MUC2 and CD10[19]. GA-FG-CCP is categorized as a purely gastric phenotype because MUC6 is strongly expressed in GA-FG-CCP which is composed of cells that mimic the fundic gland cells. In contrast, MUC5AC-postive cells, which differentiate into foveolar epithelium, are rarely detected in GA-FG-CCP[5,9,12,13]. Ueyama et al[5] speculated that MUC5AC is only expressed in advanced GA-FG-CCP lesion with a large diameter and massive submucosal invasion, suggesting that cell differentiation changes from the fundic gland type to the foveolar type during disease progression. All of the reported GA-FG-CCPs were negative for MUC2 staining, whereas a few cases displayed CD10 positivity. CD10 expression has been suggested to occur in GA-FG-CCP with a flat or depressed shape, which have an intestinal phenotype. A Flat or depressed lesion is thought to have different clinicopathological characteristics from GA-FG-CCP with an SMT-like elevated shape[12]. Immunohistochemical analysis for pepsinogen-I, the most specific marker of differentiation into chief cells, is indispensable for the diagnosis of GA-FG-CCP.

Regardless of its ability for submucosal invasion, GA-FG-CCP is generally considered to have a low potential for malignancy because none of the reported lesions displayed overexpression of p53 protein or a high labeling index of Ki-67[5,9,12,13].

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

GA-FG-CCP with an SMT-like elevated shape should be distinguished from true SMT. In particular, the possibility of diagnosis as a neuroendocrine tumor including neuroendocrine carcinoma and mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma, has been emphasized. However, there are some discriminating features between the two types of lesions. Neuroendocrine tumor has a yellow color, with few vessels on the tumor surface and a solid appearance, whereas GA-FG-CCP with an SMT-like elevated shape has a faded whitish color, with vasodilation or some branched vessels on the tumor surface and a soft appearance[12]. Histological features of GA-FG-CCP resemble those of neuroendocrine tumor: both tumors are composed small round tumor cells and originate from the deep layer. Although it is a little difficult to distinguish the two tumors by conventional hematoxylin and eosin staining, immunohhistochemical examination is useful for it. Ueyama et al[5] said these two types of lesions can be easily distinguished by immunohistochemical staining using chromogranin A. Synaptophysin and neural cell adhesion molecule are expressed in neuroendocrine tumor, but it should be noted that these markers may also be positive in GA-FG-CCP[6,20]. Moreover, pepsinogen-I positivity is the most specific finding to characterize GA-FG-CCP.

Because fundic gland polyp (FGP) resembles normal fundic gland cells and has mild atypia, GA-FG-CCP can be misdiagnosed as FGP[5,9]. Müller-Höcker et al[21] and Matsukawa et al[22] have described FGPs with chief cell hyperplasia. These lesions, which are not consistent with usual adenocarcinoma, display mild structural and nuclear atypia and a low Ki-67 labeling index, and may be GA-FG-CCP. Histological investigations by Jalving et al[23] and Stolte et al[24] demonstrated that dysplasia in FGP tends to involve the foveolar epithelium (mucosal surface), not the fundic gland (deep mucosal layer). In a report by Garrean et al[25], a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis had gastric adenocarcinomas originating from FGP, but the adenocarcinomas were thought to originate from the foveolar epithelium, not the fundic gland. These lesions associated with FGP, which have a relatively clear margin from the surrounding mucosa, do not appear to have an SMT-like elevated shape on endoscopic examination.

Gastritis cystica profunda is a distinct diagnosis, characterized by dilated glands within the submucosal layer and surrounded by a lamina propria with a normal appearance[5]. On endoscopic ultrasonography, low echoic lesions are detected in the submucosal layer, which is useful to discriminate from GA-FG-CCP with an SMT-like elevated shape[26]. Histological features that help to exclude the possibility of malignancy include the absence of cytologic atypia, lack of desmoplasia, and the presence of a surrounding lamina propria.

Early gastric cancer, normal gastric mucosa with focal atrophy, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma may resemble GA-FG-CCP with a flat or depressed shape[12]. Histopathological examination is necessary for accurate diagnosis because it is difficult to distinguish these lesions from GA-FG-CCP using endoscopy.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

Recently, the majority of GA-FG-CCPs have been treated endoscopically. GA-FG-CCP is often considered to be an indication for endoscopic resection because of its small tumor size and benign biological behavior. However, according to the 2010 version of Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines (version 3), endoscopic resection of lesions with submucosal invasion deeper than 500 μm is deemed to be inadequate with respect to curative criteria[27]. Applying this guideline to reported GA-FG-CCPs, several cases did not meet curative criteria based on the depth of massive submucosal invasion. Considering the high frequency of submucosal invasion, Kato et al[15] suggested the efficacy of the combination of laparoscopic and endoscopic approaches to neoplasia with non-exposure technique (CLEAN-NET), a form of non-exposure laparoscopy and endoscopy cooperative surgery (LECS). CLEAN-NET may represent a therapeutic option for GA-FG-CCP because it facilitates easy resection of tumors located in the upper third of stomach, whereas ESD is technically challenging. CLEAN-NET also prevents excess wall defects and dissemination of cancer cells into the peritoneal cavity. In contrast to submucosal invasion, GA-FG-CCP rarely exhibits lymphatic and venous invasion. None of the reported cases had recurrence or metastasis, except for a case with local residual recurrence. However, due to the low number of reported GA-FG-CCP cases, the rate of lymph node metastasis and long-term survival in patients with GA-FG-CCP showing massive submucosal invasion remains unclear. Taking into account that GA-FG-CCP is a low-grade malignancy and relatively common among the elderly, a future controversy will be whether an additional therapeutic approach that is suitable for general gastric adenocarcinoma should be administered to GA-FG-CCP after resection inadequate for current curative criteria[13]. GA-FG-CCP is considered to have a favorable prognosis; however, long-term follow-up investigations are necessary. Comparative surveys and prognostic analyses of cases that undergo additional therapeutic approaches or observation without treatment after resection inadequate for current curative criteria will be required.

CONCLUSION

Although GA-FG-CCP is rare, it is expected to account for an increasing proportion of gastric adenocarcinomas. In addition to reports from Japan, data on non-Japanese cases have been recently published. GA-FG-CCP tends to have the following features: (1) it originates commonly from gastric mucosa of the fundic gland region without chronic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia; (2) it is likely to be recognized as a lesion with an SMT-like elevated shape, covered by normal-colored or faded-whitish mucosa, and vasodilatation or branched vessels on the tumor surface; (3) invasion of the submucosal layer, despite only mild histological atypia and rare lymphatic or venous invasion; (4) expression of immunohistochemical markers such as MUC6 and pepsinogen-I; and (5) a low recurrence risk and favorable prognosis.

It is necessary for endoscopists to pay careful attention to the existence of GA-FG-CCP during routine examinations. Even in the absence of atrophic mucosa due to H. pylori infection, if a lesion with the above endoscopic characteristics is recognized, detailed examinations should be performed for suspected GA-FG-CCP. While a consensus on conventional white light endoscopy for diagnosis of GA-FG-CCP has recently been formed, few reports are available on advanced diagnostic endoscopy techniques such as NBI with magnification for GA-FG-CCP. Therefore, it is required to accumulate further endoscopic and histopathological data to identify the morphological characteristics of GA-FG-CCP. Furthermore, the biological characteristics of GA-FG-CCP, including its natural disease course, the rate of recurrence, and survival after resection inadequate for current curative criteria, as well as the genetic aberrations that trigger carcinogenesis remain to be elucidated.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: Authors declare no Conflict of Interests for this article.

Peer-review started: August 6, 2016

First decision: October 10, 2016

Article in press: November 28, 2016

P- Reviewer: Garcia-Olmo D, Hori K S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu WX

References

- 1.Nakamura K, Sugano H, Takagi K. Carcinoma of the stomach in incipient phase: its histogenesis and histological appearances. Gan. 1968;59:251–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kabashima A, Yao T, Sugimachi K, Tsuneyoshi M. Gastric or intestinal phenotypic expression in the carcinomas and background mucosa of multiple early gastric carcinomas. Histopathology. 2000;37:513–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.01008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao T, Utsunomiya T, Oya M, Nishiyama K, Tsuneyoshi M. Extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2510–2516. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i16.2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsukamoto T, Yokoi T, Maruta S, Kitamura M, Yamamoto T, Ban H, Tatematsu M. Gastric adenocarcinoma with chief cell differentiation. Pathol Int. 2007;57:517–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueyama H, Yao T, Nakashima Y, Hirakawa K, Oshiro Y, Hirahashi M, Iwashita A, Watanabe S. Gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type (chief cell predominant type): proposal for a new entity of gastric adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:609–619. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d94d53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukatsu H, Miyoshi H, Ishiki K, Tamura M, Yao T. Gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type (chief cell predominant type) treated with endoscopic aspiration mucosectomy. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:244–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2011.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terada T. Well differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach composed of chief cell-like cells and parietal cells (Gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type) Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2011;4:797–798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park ES, Kim YE, Park CK, Yao T, Kushima R, Kim KM. Gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type: report of three cases. Korean J Pathol. 2012;46:287–291. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2012.46.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singhi AD, Lazenby AJ, Montgomery EA. Gastric adenocarcinoma with chief cell differentiation: a proposal for reclassification as oxyntic gland polyp/adenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1030–1035. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31825033e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen WC, Rodriguez-Waitkus PM, Barroso A, Balsaver A, McKechnie JC. A rare case of gastric fundic gland adenocarcinoma (chief cell predominant type) J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:S262–S265. doi: 10.1007/s12029-012-9416-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abe T, Nagai T, Fukunaga J, Okawara H, Nakashima H, Syutou M, Kajimoto N, Wake R, Oyama T, Yao T. Long-term follow-up of gastric adenocarcinoma with chief cell differentiation using upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy. Intern Med. 2013;52:1585–1588. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueyama H, Matsumoto K, Nagahara A, Hayashi T, Yao T, Watanabe S. Gastric adenocarcinoma of the fundic gland type (chief cell predominant type) Endoscopy. 2014;46:153–157. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1359042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyazawa M, Matsuda M, Yano M, Hara Y, Arihara F, Horita Y, Matsuda K, Sakai A, Noda Y. Gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type: Five cases treated with endoscopic resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8208–8214. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i26.8208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parikh ND, Gibson J, Aslanian H. Gastric Fundic Gland Adenocarcinoma With Chief Cell Differentiation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:A17–A18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kato M, Uraoka T, Isobe Y, Abe K, Hirata T, Takada Y, Wada M, Takatori Y, Takabayashi K, Fujiyama Y, et al. A case of gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type resected by combination of laparoscopic and endoscopic approaches to neoplasia with non-exposure technique (CLEAN-NET) Clin J Gastroenterol. 2015;8:393–399. doi: 10.1007/s12328-015-0619-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujii M, Uedo N, Ishihara R, Aoi K, Matsuura N, Ito T, Yamashina T, Hanaoka N, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, et al. Endoscopic features of early stage gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type (chief cell predominant type): a case report. Case Rep Clin Pathol. 2015;2:17. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuda A, Matsuda T, Shibata A, Katanoda K, Sobue T, Nishimoto H. Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2008: a study of 25 population-based cancer registries for the Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:388–396. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao K, Anagnostopoulos GK, Ragunath K. Magnifying endoscopy for diagnosing and delineating early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2009;41:462–467. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsukashita S, Kushima R, Bamba M, Sugihara H, Hattori T. MUC gene expression and histogenesis of adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:166–170. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yao T, Ueyama H, Kushima R, Nakashima Y, Hirakawa K, Ohshiro Y, Hirano H, Satake T, Shimizu S, Yamane T, et al. New type of gastric carcinoma-Adenocarcinoma of the fundic gland type: its clinicopathological features and tumor development. Stomach Intest. 2010;45:1203–1211. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller-Höcker J, Rellecke P. Chief cell proliferation of the gastric mucosa mimicking early gastric cancer: an unusual variant of fundic gland polyp. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:496–500. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsukawa A, Kurano R, Takemoto T, Kagayama M, Ito T. Chief cell hyperplasia with structural and nuclear atypia: a variant of fundic gland polyp. Pathol Res Pract. 2005;200:817–821. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jalving M, Koornstra JJ, Boersma-van Ek W, de Jong S, Karrenbeld A, Hollema H, de Vries EG, Kleibeuker JH. Dysplasia in fundic gland polyps is associated with nuclear beta-catenin expression and relatively high cell turnover rates. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:916–922. doi: 10.1080/00365520310005433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stolte M, Vieth M, Ebert MP. High-grade dysplasia in sporadic fundic gland polyps: clinically relevant or not? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:1153–1156. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrean S, Hering J, Saied A, Jani J, Espat NJ. Gastric adenocarcinoma arising from fundic gland polyps in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome. Am Surg. 2008;74:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Machicado J, Shroff J, Quesada A, Jelinek K, Spinn MP, Scott LD, Thosani N. Gastritis cystica profunda: Endoscopic ultrasound findings and review of the literature. Endosc Ultrasound. 2014;3:131–134. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.131041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3) Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–123. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]