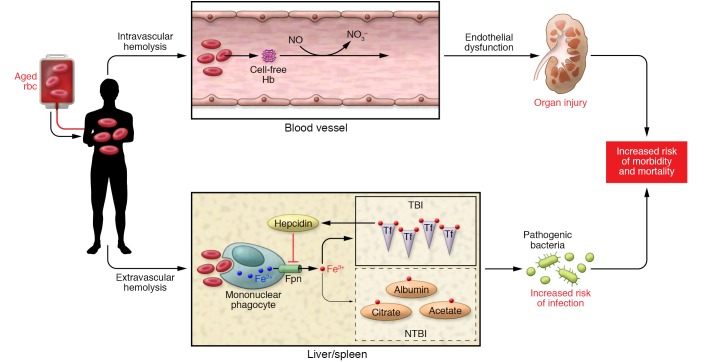

Figure 1. Schematic representation of aged rbc transfusion effects.

Intravascular hemolysis occurs, resulting in the release of breakdown products from aged rbc and cell-free hemoglobin (Hb, represented by cell-free Hb). Additionally, scavenging of NO occurs through the dioxygenation reaction. Release of arginase from lysing rbc also reduces the substrate l-arginine for NO synthase, further reducing NO bioavailability (not depicted). Reduced NO decreases vessel smooth muscle relaxation and contributes to endothelial dysfunction, with consequent organ injury. Extravascular hemolysis occurs when damaged rbc are acutely delivered and exceed the capacity of the mononuclear phagocyte system of the liver and spleen. Aged rbc are phagocytosed, heme is catabolized, and iron is ultimately released through the ferroportin (Fpn) export system and taken up by transferrin (Tf), the major iron transport protein in the body. With aged rbc transfusion, the large amount of iron exported out of the monocyte/macrophage results in the development of NTBI — iron complexed to other compounds such as albumin, citrate, etc. The disruption in iron handling may provide a readily available source of iron for pathogens and increase infectious risk in susceptible hosts. Note that a rise in transferrin-bound iron also occurs and provides a feedback loop to increase hepcidin, which negatively regulates iron export through ferroportin. However, this compensatory mechanism is insufficient to avoid formation of NTBI. For simplicity, only key elements of the two pathways are depicted.