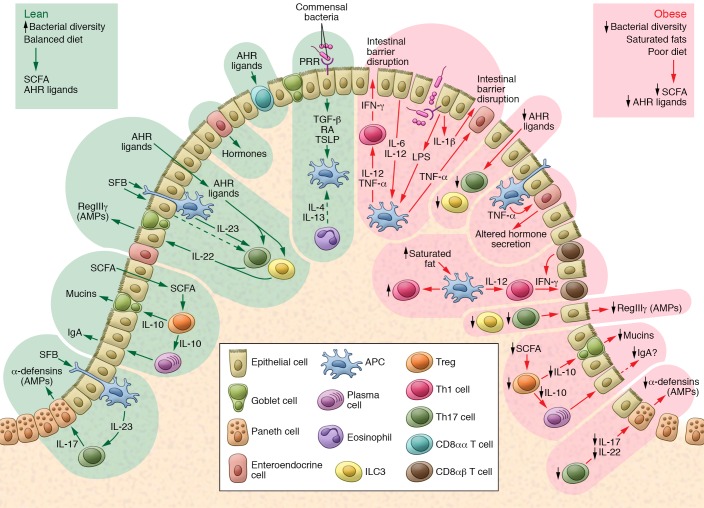

Figure 1. Dietary and microbial cues influence intestinal immunity during diet-induced obesity.

During intestinal homeostasis in the lean state (left), microbial metabolites, including SCFAs (e.g., butyrate), improve intestinal barrier function through promotion of Treg function. Treg-derived IL-10 in turn may boost mucin production. Apical signaling of commensal organisms through select PRRs also promote production of the largely antiinflammatory mediators TGF-β, retinoic acid (RA), and TSLP, which maintains intestinal tolerance. Products such as AHR ligands derived from dietary fruits and vegetables fuel the function of groups of immune cells (e.g., ILC3s and CD8αα T cells; arrows lead from AHR ligands to ILC3s and Th17 cells), which produce mediators that maintain the epithelial barrier. During diet-induced obesity (right) there is an increase in saturated fats coupled with a reduction in fibers and associated bacterial dysbiosis. These alterations lead to a state of low-grade chronic inflammatory changes in local immune populations, which have numerous effects on intestinal homeostasis. The relative reductions in IL-10, coupled with increasing local TNF-α, may compromise mucin production and IgA class switching and affect gut hormone secretion. The restriction in bacterial diversity, coupled with reductions in AHR ligands from a lack of fruits and vegetables, leads to a reduction in ILC3s, CD8αα T cells, and Th17 cells, which maintain barrier integrity. This overall reduction in intestinal barrier integrity promotes leakage of bacterial products such as LPS, which helps support a shift in T cell polarity to IFN-γ–releasing Th1 T cells. The ensuing low-grade inflammation further compromises intestinal barrier function, resulting in the characteristic permeable barrier associated with diet-induced obesity.