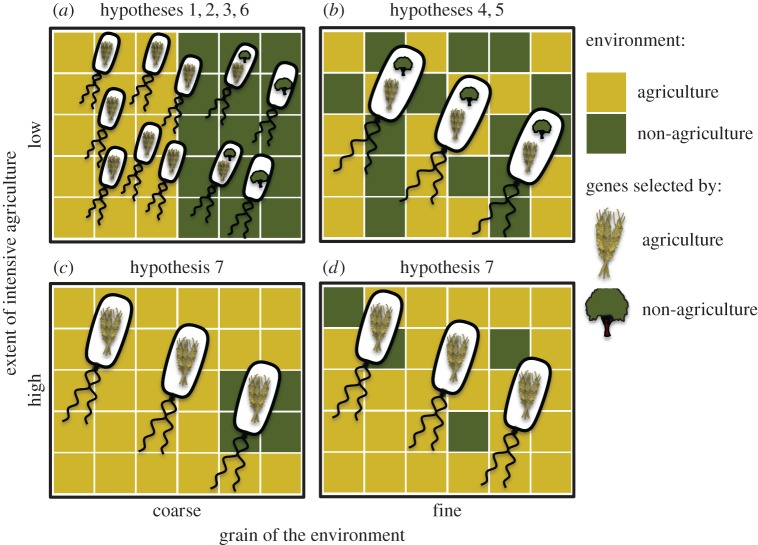

Figure 1.

Illustration of some of the hypotheses discussed in the main text. Each panel is a landscape, with different colours indicating different habitat types (agriculture or no agriculture). The landscapes are arranged to illustrate coarse-grained (habitat patch size much larger than dispersal range, left column) and fine-grained (habitat patch size similar to- or smaller than dispersal range, right column) landscapes, as well as landscapes more (bottom row) or less (top row) dominated by intensive agriculture. Bacterial cells are placed across the landscape and the symbol inside represents the habitats to which they are best adapted. (a) Ecotypes are locally adapted to agriculture and non-agriculture environments, as described in hypothesis 1. Owing to the extent of the area under agricultural intensification, genes or species spill over into adjacent non-agriculture areas (hypothesis 2), creating a halo of niche differentiation either of agriculture-adapted strains (hypothesis 3) or introgression of genes selected under agriculture (hypothesis 6). (b) Finer-grained environments select for generalist strains, with adaptations to both agriculture and non-agricultural environments, because both environments are encountered (hypothesis 5). Equivalently, strains with higher dispersal abilities will select for generalist species (hypothesis 4). (c) Increasing the extent of intensive agriculture will result in landscapes dominated by agriculture specialists, because spillover from agriculture swamps locally adapted strains in non-agriculture environments, resulting in a loss of beta diversity (hypothesis 7). (d) The grain of the environment has a weaker effect on bacterial populations when the extent of intensive agriculture is high.