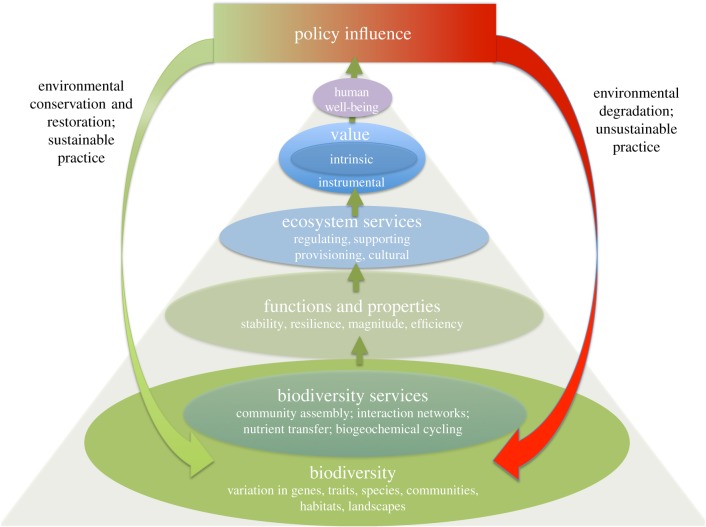

Figure 1.

The value of biodiversity to human well-being. Biodiversity is structured by a range of ecological processes including: (i) community assembly (the biotic and abiotic interactions, including environmental filtering, competition and host–parasite interactions, which together determine the distribution of species and their abundance in communities), (ii) interaction networks (the architecture of mutualistic and antagonistic interactions underlying pollination, seed dispersal, predator–prey cycles, etc.), (iii) nutrient transfer (the breakdown of nutrients and transfer across the environment), and (iv) biogeochemical cycling (the cycling of chemicals, e.g. C, N, through the biosphere and lithosphere). These processes—which can be termed ‘biodiversity services’—underpin and determine the stability, resilience, magnitude and efficiency of the functions and properties of ecosystems. Those functions and properties that benefit people are referred to as ‘ecosystem services’ and reflect what it is we tend to value about biodiversity. Values are divided into intrinsic (which by definition cannot be valued economically) and instrumental values (that contribute to human welfare in many and varied direct and indirect ways). When economic valuation is done correctly (i.e. robust assessment and weighting of values), the outcome is green environmental policy (left, green arrow implying positive effects on biodiversity and ecosystems) that leads to environmental conservation, restoration, protection and sustainable practice. When done incorrectly, it can lead to environmental degradation and unsustainable practice (right, red arrow, implying harmful effects on biodiversity and ecosystems). Two elements of this framework are therefore critical; the natural science underpinning biodiversity's influence over ecosystem functions and properties, and the social science underpinning values and valuations. If incomplete, poorly done or ignored, policy is more likely to be red than green.