Abstract

Multistability in perception is a powerful tool for investigating sensory–perceptual transformations, because it produces dissociations between sensory inputs and subjective experience. Spontaneous switching between different perceptual objects occurs during prolonged listening to a sound sequence of tone triplets or repeated words (termed auditory streaming and verbal transformations, respectively). We used these examples of auditory multistability to examine to what extent neurochemical and cognitive factors influence the observed idiosyncratic patterns of switching between perceptual objects. The concentrations of glutamate–glutamine (Glx) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in brain regions were measured by magnetic resonance spectroscopy, while personality traits and executive functions were assessed using questionnaires and response inhibition tasks. Idiosyncratic patterns of perceptual switching in the two multistable stimulus configurations were identified using a multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis. Intriguingly, although switching patterns within each individual differed between auditory streaming and verbal transformations, similar MDS dimensions were extracted separately from the two datasets. Individual switching patterns were significantly correlated with Glx and GABA concentrations in auditory cortex and inferior frontal cortex but not with the personality traits and executive functions. Our results suggest that auditory perceptual organization depends on the balance between neural excitation and inhibition in different brain regions.

This article is part of the themed issue ‘Auditory and visual scene analysis'.

Keywords: perceptual organization, individual differences, auditory streaming, verbal transformations, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, neurotransmitters

1. Introduction

An essential function of perceptual systems is to parse complex scenes into meaningful components. The sequential integration and segregation of frequency components play a critical role in auditory scene analysis because sound sources produce information over time [1]. Multistable perceptual phenomena, such as auditory streaming have been used to identify the factors influencing auditory scene analysis [2,3] (see also [4,5]). A sequence of repeating tone triplets (ABA, where A and B differ in frequency) is presented in the auditory streaming paradigm [6]. The perceptual organization depends on the frequency difference between the A and B tones and the presentation rate: a small difference and slow presentation favour integration (i.e. all tones experienced as a single stream), whereas a large separation and fast presentation favour segregation (i.e. two separate streams). For intermediate differences and presentation rates, perception tends to switch between the two types of percept [7]. Recent studies using auditory streaming have pointed out that listeners can experience three or more types of perceptual organization, such as integrated, segregated and combined percepts [8–10]. In verbal transformations, a series of perceptual switches is produced by prolonged listening to a repeated word without a pause [11,12]. For instance, the stimulus ‘tress’ may be transformed into a variety of verbal forms, such as ‘dress’, ‘stress’ and ‘drest’ [13]. In daily life, we sometimes have difficulty taking signals from acoustic inputs because of various types of noise. From the perspective of adaptive behaviour, it is important for the brain to create some possible percepts from ambiguous inputs and fluctuate perceptual interpretations of them. Thus, these paradigms are simple but important for investigating our abilities to identify sound events, communicate with others and enjoy music.

Multistable stimuli induce successive spontaneous switches between different perceptual objects, in a seemingly random manner [14]. A recent study has demonstrated that perceptual switching patterns are idiosyncratic: the switching patterns of each participant are more similar to their own switching patterns in different sessions than to those of other participants and this tendency is preserved even when sessions are separated by more than a year [9]. This raises the following question: what are the idiosyncratic factors of perceptual switching?

One possibility is that genetic or anatomical differences are responsible for interindividual variations in multistable perception. A twin heritability study has revealed that 50% of the variance in the binocular rivalry rate is explained by additive genetic factors [15]. The dopaminergic system has been linked with individual differences of perceptual switching in auditory streaming and verbal transformations [16,17]. Brain structures, such as regional cortical volumes [18] and interregional connections [19], are associated with spontaneous switching in visual rivalry. However, few studies have examined whether neurochemical factors in the brain contribute to the stability of idiosyncratic switching patterns in an auditory multistable task. Computational models with mutual inhibition and sensory adaptation have been proposed to account for the nonlinear dynamics of perceptual multistability [20–24]. In these models, perceptual switching is driven by adaptation of the winning neural population and lateral inhibition of the competing population [25]. Thus, we can expect that the excitation–inhibition balance plays an important role in perceptual multistability. However, it is essentially difficult to elucidate the excitation–inhibition balance of brain activations, because both processes are activity dependent but in fundamentally different ways [26]. To overcome this difficulty, we used magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to measure the concentration of glutamate–glutamine (Glx) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) within brain regions. In the cerebral cortex, roughly 80% of the neurons are excitatory glutamatergic and 20% are inhibitory GABAergic neurons [27]. The ratio of synaptic neurotransmitters plays a key role in coordinating the pyramidal cell activity and in driving the haemodynamic response. Specifically, MRS studies have demonstrated that the GABA concentration in different cortical areas predicts individual differences in visual awareness [28], visual attention [29,30] and orientation discrimination [31]. However, it is unclear to what degree neurotransmitter systems are involved in the formation and selection of auditory objects.

Another approach is to search for high-level processes related to switching patterns for each individual [32–34]. Although the frontal areas are probably responsible for perceptual switching in different multistable stimuli [35–37], there is little evidence for a link between personality traits and switching patterns, except for the results of one recent study [38]. We assessed personality traits and executive functions to investigate whether cognitive abilities are associated with individual differences in perceptual switching. Perceptual organization may also be influenced by the big five traits (measured by the Big Five Inventory [39]), which are considered to be the basic broad domains of personality. Behavioural impulsivity and flexibility have been measured by using the UPPS Impulsive Behaviour Inventory [40] and ego-resiliency scale [41,42], respectively. Inhibitory control is thought to be one of the important executive functions [43]. This study focused on inhibition of a prepotent response to test the possible role of cognitive-level inhibition processes in perceptual organization. We extracted several variables for auditory streaming and verbal transformations and computed correlations between perceptual variables, neurotransmitter measures, personality traits, and response inhibition abilities.

2. Material and methods

(a). Participants

We recruited 34 Japanese participants (24 males and 10 females; 21–60 years, Mage = 36.3, s.d.age = 11.2) for this study. The score of the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory [44] was 94.8 ± 5.2, indicating that they were strongly right-handed. None had any history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. On the basis of the performance of catch trials, we excluded 11 participants from subsequent analyses (see the electronic supplementary material, Data Analysis for details). One additional participant was discarded because she did not complete the verbal transformations task. Thus, the reported results were derived from 22 participants (16 males and 6 females; 21–58 years, Mage = 32.6, s.d.age = 10.7).

(b). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy data acquisition

MRS data were acquired with a Siemens MAGNETOM Trio 3T MRI scanner with a 12-channel receive-only head coil. Head motion was minimized with comfortable padding around the participant's head. For assessment of cortical thickness and volume, anatomical images were obtained with a T1-weighted pulse sequence (isotropic voxel size of 1 mm3). To minimize confounding factors, we acquired MR spectra at a fixed time during the day, which was one and a half hours from 13.00 to 14.30.

MR spectra were acquired from four 3 × 3 × 3 cm3 voxels of interest: the auditory cortex (AC), inferior frontal cortex (IFC), prefrontal cortex (PFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; electronic supplementary material, figure S1a). Voxels were positioned by using internal landmarks in order to achieve a consistent position between participants. The AC voxel included Heschl's gyrus (Brodmann area: BA 41) and the anterior part of the temporal plane (BA 42). The IFC voxel included the pars opercularis (BA 44) and pars triangularis (BA 45) of the inferior frontal gyrus. The PFC voxel was located at the anterior part of the middle frontal gyrus (BA 46). The ACC voxel (including portions of BAs 32 and 9) was located superior to the genu of the corpus callosum and centred on the interhemispheric fissure. All voxels except the ACC one were angled parallel to the brain surface of the left hemisphere. For each participant, voxels were separately placed to exclude cerebral spinal fluid from the ventricles or the cortical surface.

Four consecutive runs were acquired from the different voxels for each participant. Before each run, we carefully carried out manual shimming (approx. 5 min) of the magnetic field in the voxel to avoid line broadening. MR spectra were obtained by using a GABA spectral editing sequence. For each spectrum, 64 spectral averages of 1024 data points were acquired with a repetition time of 1500 ms and an echo time of 68 ms, resulting in scan duration of 3 min 18 s. We used the short duration to reduce effects of head motion on MR spectra. An editing pulse with bandwidth of 44 Hz was applied at 1.9 ppm (on) and 7.5 ppm (off) in interleaved scans. Differences in the edited spectra yielded the Glx and GABA peaks (electronic supplementary material, figure S1b). The unsuppressed water signal was also acquired from the same voxel.

Gannet and in-house software was used to quantify total Glx and GABA in the difference spectra [45]. All spectra were phase aligned with reference to water, frequency aligned to creatine and modelled with a simple Gaussian function. The final results were expressed as the ratio of Glx and GABA signal areas (peaks at 3.76 and 3.00 ppm, respectively) relative to the unsuppressed water signal area (W). The Glx/W and GABA/W concentrations were quantified in institutional unit (i.u.) [46]. The Glx/W and GABA/W concentrations (mean ± s.e.) were 1.23 ± 0.03 i.u. and 1.71 ± 0.06 i.u. for AC; 1.19 ± 0.05 i.u. and 1.55 ± 0.08 i.u. for IFC; 1.13 ± 0.05 i.u. and 1.43 ± 0.08 i.u. for PFC; and 1.06 ± 0.04 i.u. and 1.30 ± 0.05 i.u. for ACC. The fit errors related to the Glx/W and GABA/W values were 13.2 ± 0.8% and 8.5 ± 0.4% for AC; 15.7 ± 0.7% and 11.7 ± 0.5% for IFC; 15.2 ± 0.7% and 11.3 ± 0.5% for PFC; and 16.6 ± 0.6% and 9.9 ± 0.5% for ACC.

(c). Task procedures

Right after the MRS data acquisition, participants performed the multistability tasks and response inhibition tasks and filled out the personality questionnaires in a quiet room. The behavioural tasks were controlled by the Cogent 2000 Toolbox running under MATLAB (Mathworks Inc.) on a PC, whereas the personality questionnaires, consisting of the Big Five Inventory, the UPPS Impulsive Behaviour Inventory and ego-resiliency scale, were pen-and-paper tests. The order of these tests was randomized across participants.

For auditory streaming, the stimuli and task procedures were identical to those used in our previous studies [38,47]. The streaming stimulus was a 4-min-long sequence of a repeating ABA-pattern, where the frequency of the A tone was 400 Hz and the frequency difference between the A and B tones was four semitones. The tones had a duration of 75 ms, and the stimulus onset asynchrony was 150 ms. Participants were instructed to continuously report their perception by holding down the assigned arrow key on a computer keyboard for as long as they perceived the tones in the same way. Participants were given four alternatives for categorizing their perception: integrated (ABA-ABA-), segregated (A-A- and -B---B--), combined (AB-- and --A- or -BA- and A---) and none (none of the above possibilities). The five test blocks were preceded by training blocks, where participants practised reporting their perception confidently and precisely.

For the verbal transformations, the stimulus consisted of repetitions of the word ‘banana’, spoken by a female native Japanese speaker [37]. Participants heard the word for 340 ms without gaps while refraining from silently repeating it. They were asked to continuously indicate the word they heard by holding down the assigned arrow keys on a computer keyboard. The alternatives to be marked were banana, nappa (‘vegetables’ in English), some nonsense word, or some other word (i.e. actual Japanese words other than banana and nappa), and none (undecided). Five 4-min blocks were conducted for verbal transformations for comparability with the auditory streaming task.

Three inhibition tasks were employed to assess participants' ability to inhibit automatic or prepotent responses. Although the term of ‘inhibition’ is commonly used to describe a wide variety of functions, the concept of inhibition in this study is restricted to the controlled suppression of dominant responses. In the antisaccade task, a visual cue was followed by a target, and participants had to suppress stimulus-driven attention induced by the cue. The stop-signal task was similar to a go/nogo task, but required them to inhibit an already initiated motor response. Thus, in addition to response accuracies, latencies to stop a response could be calculated. In the Stroop task, participants had to resolve name–colour conflicts and provide a response verbally. The detailed procedures of personality questionnaires and inhibition tasks are described in the electronic supplementary material, Task Procedures and figure S2. The scores for all items of the personality scales were summed to produce the subscale scores. The reliabilities reached a satisfactory level (range of 0.73–0.88). A summary of descriptive statistics for the personality scales and inhibition tasks is shown in the electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S2.

(d). Data analysis

For the auditory streaming paradigm, catch trails were used to exclude participants who likely did not fully understand the instructions (see the electronic supplementary material, Data Analysis for details). Each of the possible perceptual alternatives were promoted in the catch trials. On the basis of catch-trial performance, we excluded participants from further analysis if their correct identification of the disambiguated integrated, segregated or combined percept fell below 30% or their composite correct score was less than 60% [47]. The data for 11 participants were removed, making the sample size 22.

For each multistability task, the time-series data of phase durations were collected from all test blocks. Phases shorter than 300 ms were excluded from data analyses [48], resulting in 99.7% of the analysed data. Results of a previous study suggested that the first block should be discarded from the analysis because the switching pattern in this block substantially differs from that in the rest of the blocks [47]. The following analyses were based on blocks two to five (electronic supplementary material, figure S3a). In addition, the first phase was removed from each block, because the first phase duration is known to be longer than that of the subsequent ones [7,49]. Individual switching patterns were characterized by using transition matrices, which represent the conditional probabilities of perceptual switches [10]. We modelled time-series switching data using a Markov chain of four types of percepts in auditory streaming and five types of percepts in verbal transformations. The parameters of a Markov chain were used to calculate transition probabilities from one to the other percepts. The transition matrices include several measures of switching patterns, such as switch numbers, phase durations and percept proportions.

The number of perceptual switches and the durations of each percept were extracted from transition matrices. For auditory streaming, the number of switches across blocks was 35.8 ± 24.6 (mean ± s.e.). The phase durations were 14.7 ± 13.3 s for integrated, 7.5 ± 5.8 s for segregated, 6.6 ± 4.9 s for combined and 1.5 ± 1.4 s for none. The proportions of the percepts were 49.0 ± 18.7% for integrated, 27.3 ± 11.8% for segregated, 23.4 ± 23.9% for combined and 0.3 ± 0.5% for none. For verbal transformations, the number of switches was 32.5 ± 18.8. The phase durations were 19.3 ± 49.8 s for banana, 9.2 ± 8.0 s for nappa, 10.4 ± 7.5 s for nonsense, 10.2 ± 6.2 s for others and 4.5 ± 1.8 s for none. The proportions of the percepts were 26.8 ± 20.1% for banana, 31.7 ± 15.5% for nappa, 19.0 ± 13.7% for nonsense, 20.7 ± 16.6% for other percepts and 1.8 ± 0.0% for none.

The time to discover all percepts was calculated by simulating the switching patterns using the transition matrices [38]. Short discovery times suggest that all alternatives are relatively easy to perceive for the given participant, whereas long discovery times suggest that some perceptual alternatives are less viable. We ran the simulation 1000 times for each participant until all percepts were discovered. The median time of the simulations was used as the ‘time to discover all percepts’ variable of the participant. The times to discover all percepts were 24.4 ± 33.4 s for auditory streaming and 197.7 ± 180.4 s for verbal transformations.

The transition matrices were suitable for comparing individuals based on multidimensional scaling (MDS) of their switching patterns (see also the electronic supplementary material, Data Analysis). A scree test was performed to decide on the number of dimensions in the MDS (electronic supplementary material, figure S3b). A smaller stress value (less than 0.05) indicates that the dataset is well represented by the corresponding number of MDS dimensions [50]. To interpret the MDS dimensions, we assessed the extent to which the coordinates of each participant were correlated with the following variables: for auditory streaming, the number of switches, the time to discover all percepts, the durations and proportions of the integrated, segregated and combined percepts; for verbal transformations, the durations and proportions of the banana, nappa, nonsense and others.

We calculated significance levels by Spearman's rank order correlations using two methods. The first approach was to estimate the probability of obtaining the correlation by a random projection of the factor values. The probability was determined by permuting the factor vectors 10 000 times and establishing the proportion of random correlations that were higher than the one obtained empirically (pperm). The second approach was to control for the family-wise error rate in this randomization context by registering the highest absolute correlation between the given MDS dimension and each perceptual variable in each permutation run. The distribution of these maximal coefficients was then used to compute the p-value of the observed correlations (pfwe). Variables were sorted into five families: perceptual measures (eight variables in auditory streaming and 10 variables in verbal transformations); Glx measures in the four brain regions (AC, IFC, PFC and ACC); GABA measures derived from the same brain regions as the Glx measures; personality traits (10 variables of the personality scales) and measures from the inhibition tasks (accuracy of antisaccade trials, stop-signal reaction time and reaction time difference in the Stroop task).

3. Results

Idiosyncratic switching patterns were first checked by using the intraindividual difference calculated from the Kullback–Leibler (KL) distances between participant's own transition matrices across blocks (electronic supplementary material, figure S3c). Then interindividual difference was assessed by computing the KL distances between the participant's and every other participants' transition matrices. The relationship between a participant's intra- and interindividual consistency was tested by Wilcoxon's signed-rank test. The hypothesis was that the intraindividual distances would be smaller than the interindividual ones. Thus, we used a one-tailed test for each participant (α-level = 0.05).

Using the transition matrices from auditory streaming, 17 of the 22 participants (77.3%) were distinguishable from the rest of the participants (electronic supplementary material, table S3). Using the number of switches variable, 15 of the 22 participants (68.2%) were separable from the rest. For verbal transformations, the transition matrices allowed 15 of the 22 participant (68.2%) to be distinguished from the rest of the participants, whereas by the number of switches, 16 of the 22 participants (72.7%) were separable from the rest. In both auditory streaming and verbal transformations, 14 participants (63.6%) had characteristic transition matrices, although only 10 participants (45.5%) had characteristic switch numbers. The transition matrices were chosen for the MDS because it led to similar results reflecting characteristic switching patterns for each individual.

The MDS was used to examine relationships between individual cases in the auditory streaming dataset (table 1). A two-dimensional solution gave an acceptable fit to the data (stress = 0.028; electronic supplementary material, figure S3b). The first dimension was positively related to the proportion of the combined percept (rs = 0.986), whereas it was negatively related to the proportion of the integrated and segregated percepts (rs = −0.744 and −0.666). The first dimension also showed negative correlations with the duration of integrated and segregated percepts (rs = −0.614 and −0.604). Because integrated and segregated percepts are the most frequent ones in a classic streaming paradigm [6], our interpretation is that the first dimension is strongly affected by the presence of the additional option of describing one's perception in terms of the combined percept. Thus, the first dimension was named the ‘exploration–exploitation’ axis. This idea is consistent with the evidence that participants with high scores on the first dimension discovered all percepts quickly (rs = −0.495). The second dimension was positively related to the proportion of the integrated percept (rs = 0.540) and negatively to that of the segregated percept (rs = −0.572). Thus, the second dimension was termed the ‘integration–segregation’ axis. Taken together, these results suggest that the listener's task to categorize their perception in terms of multiple alternatives produces distinct individual differences in auditory streaming and that these differences can be mapped on two dimensions.

Table 1.

MDS dimensions derived from auditory streaming variables. Values indicated in italics are significant (p < 0.05, N = 22). rs, Spearman's rank order correlation coefficient; pperm, permutated p-value; pfwe, family-wise error controlled p-value.

| first dimension |

second dimension |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| measure | rs | pperm | pfwe | rs | pperm | pfwe |

| duration of integrated | −0.614 | 0.003 | 0.020 | 0.312 | 0.160 | 0.568 |

| duration of segregated | −0.604 | 0.002 | 0.024 | −0.085 | 0.703 | 0.999 |

| duration of combined | 0.208 | 0.352 | 0.872 | 0.022 | 0.923 | 1.000 |

| proportion of integrated | −0.774 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.540 | 0.011 | 0.063 |

| proportion of segregated | −0.666 | <0.001 | 0.007 | −0.572 | 0.007 | 0.036 |

| proportion of combined | 0.986 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.172 | 0.439 | 0.940 |

| number of switches | 0.422 | 0.057 | 0.244 | −0.211 | 0.344 | 0.863 |

| time to discover all percepts | −0.495 | 0.023 | 0.111 | 0.605 | 0.002 | 0.022 |

We identified the neurotransmitter measures associated with switching patterns of auditory streaming (electronic supplementary material, table S4). The Glx in the AC was negatively correlated with the ‘exploration–exploitation’ dimension (rs = −0.550, pperm = 0.007, pfwe = 0.039), but the other variables were not. This suggests that higher Glx concentration in this region is related to the ‘exploitation’ property of auditory streaming. We further examined the relationship between neurotransmitter measures and perceptual variables. The Glx in the AC was correlated positively with the proportion of the segregated percept (rs = 0.761, pperm = 0.001, pfwe = 0.001) and negatively with that of the combined percept (rs = −0.520, pperm = 0.014, pfwe = 0.050; figure 1a). This confirms that participants with a higher Glx concentration in the AC experience more segregated and fewer combined percepts. It has been found that neural responses in the AC can account for important features of auditory streaming [51–54]. Here, we argue that the formation and selection of the combined percept also requires other brain areas. One possible candidate is the IFC, because the GABA measured there was related positively to the proportion of the combined percept (rs = 0.446, pperm = 0.041, pfwe = 0.138) and negatively to the duration of the segregated percept (rs = −0.425, pperm = 0.050, pfwe = 0.185; figure 1b). Thus, it is possible that the ‘exploration–exploitation’ property of auditory streaming is supported by a balance between Glx and GABA concentrations in different brain regions.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots of neurotransmitter concentrations and auditory streaming variables. Symbols indicate individual data. Grubbs test did not reveal any outliers for the variables.

MDS was also used to examine what separates individuals' switching patterns in verbal transformations (table 2). A three-dimensional solution was chosen (stress = 0.014; electronic supplementary material, figure S3b). The first dimension was related positively to the proportion of banana (rs = 0.816) and negatively to that of others (rs = −0.906). The second and third dimensions were negatively correlated with the proportion of nappa (rs = −0.966) and nonsense (rs = −0.868). These results indicate that the proportion of each percept, rather than its duration, is associated with individual differences in verbal transformations.

Table 2.

MDS dimensions derived from verbal transformations variables. Values in italics are significant (p < 0.05, N = 22).

| first dimension |

second dimension |

third dimension |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| measure | rs | pperm | pfwe | rs | pperm | pfwe | rs | pperm | pfwe |

| duration of banana | 0.318 | 0.145 | 0.677 | 0.287 | 0.193 | 0.771 | 0.095 | 0.671 | 1.000 |

| duration of nappa | −0.036 | 0.872 | 1.000 | −0.271 | 0.222 | 0.820 | 0.012 | 0.958 | 1.000 |

| duration of nonsense | −0.064 | 0.778 | 1.000 | 0.091 | 0.685 | 1.000 | 0.007 | 0.972 | 1.000 |

| duration of others | −0.419 | 0.058 | 0.344 | 0.041 | 0.854 | 1.000 | 0.069 | 0.761 | 1.000 |

| proportion of banana | 0.816 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.250 | 0.261 | 0.876 | 0.355 | 0.104 | 0.553 |

| proportion of nappa | 0.142 | 0.518 | 0.995 | −0.966 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.080 | 0.732 | 1.000 |

| proportion of nonsense | −0.191 | 0.397 | 0.965 | 0.403 | 0.068 | 0.384 | −0.868 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| proportion of others | −0.906 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.029 | 0.898 | 1.000 | 0.414 | 0.056 | 0.353 |

| number of switches | −0.027 | 0.909 | 1.000 | −0.187 | 0.405 | 0.972 | −0.177 | 0.433 | 0.977 |

| time to discover all percepts | 0.465 | 0.031 | 0.218 | −0.169 | 0.445 | 0.982 | 0.110 | 0.622 | 0.999 |

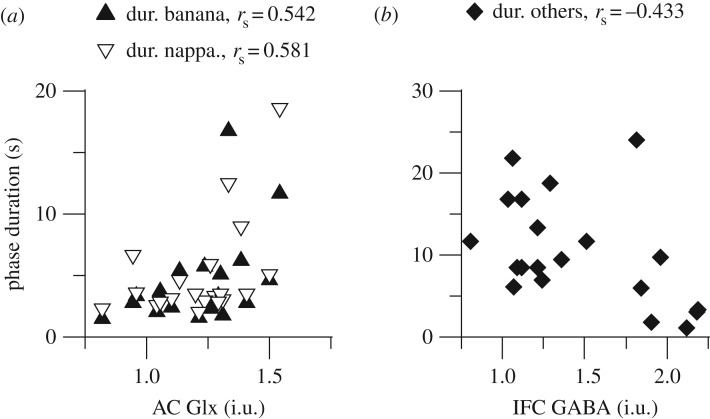

Neurotransmitter measures did not show any significant correlation with the MDS dimensions of verbal transformations (electronic supplementary material, table S5). We then investigated the relationship between neurotransmitter measures and perceptual variables. The Glx concentration in the AC was related positively to the duration of banana (rs = 0.542, pperm = 0.011, pfwe = 0.042) and nappa (rs = 0.581, pperm = 0.005, pfwe = 0.021; figure 2a) and negatively to the number of switches (rs = −0.539, pperm = 0.010, pfwe = 0.010). The Glx concentration in the AC showed a negative correlation with the time to discover all percepts (rs = −0.539, pperm = 0.010, pfwe = 0.157). Given that banana and nappa are the most common percepts in this variant of verbal transformations, the pattern of correlations described is partly consistent with that obtained for auditory streaming. In addition, the GABA in the IFC was related to the duration of others (rs = −0.433, pperm = 0.042, pfwe = 0.167; figure 2b). Thus, there is the possibility that Glx and GABA concentrations in the AC and IFC contribute to durations of verbal forms.

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of neurotransmitter concentrations and verbal transformations variables. Symbols indicate individual data. Grubbs test did not reveal any outliers for the variables.

The first MDS dimension of auditory streaming was not related to the first (r = 0.132, p = 0.559), second (r = 0.167, p = 0.457) and third MDS dimensions of verbal transformations (r = −0.147, p = 0.514). The same was true for the second MDS dimension of auditory streaming for the first (r = 0.017, p = 0.940), second (r = 0.089, p = 0.692) and third MDS dimensions of verbal transformations (r = 0.380, p = 0.081). Thus, an MDS position in one multistability task does not appear to be related to the MDS position in the other task. For the personality scales and response inhibition tasks, we did not find any measure that significantly correlated with any of the MDS dimensions of the switching patterns (electronic supplementary material, tables S6–S9).

4. Discussion

The present results demonstrated that Glx and GABA concentrations in the AC and IFC were related to idiosyncratic switching patterns of auditory streaming and verbal transformations. By contrast, we found no evidence that neurotransmitter concentrations in PFC and ACC contributed to individual differences in the switching patterns. This lack of correlation is consistent with recent neuroimaging evidence in visual bistable perception [55]. Thus, the interindividual variation of auditory multistability can be linked to the balance of glutamatergic and GABAergic signalling between different brain regions. We did not find any correlation between perceptual switching patterns, personality traits and response inhibition abilities. Thus, cognitive factors probably have a limited effect on auditory multistability.

We acquired the following two dimensions from the transition matrices of auditory streaming: ‘exploration–exploitation’ and ‘integration–segregation’. The MDS results in this study are consistent with those obtained in a recent study [38]. The dimensions probably reflect a general principle of switching patterns in auditory streaming, beyond language and culture, because similar results are obtained in laboratories in different countries. More importantly, Glx concentrations in the AC were correlated with the proportion of the integrated and segregated percepts (i.e. more exploitation), whereas GABA concentrations in the IFC were correlated with the proportion of the combined percept and the short time to discover all percepts (i.e. more exploration). This suggests that switching patterns are based on the balance of Glx and GABA concentrations between sensory and suprasensory areas. Although most neuroimaging studies have focused on the role of AC in perceptual organization [52,53,56], several researchers have argued that the intraparietal sulcus mediates the figure-ground segregation in auditory scenes [57,58]. Thus, there is the possibility that an interaction between different cortical areas is responsible for individual differences in auditory multistability. The previous studies mentioned above allowed only two choices for participants to report their percepts of sound sequences, whereas this study allowed them four alternatives. The latter possibly involves schema-based processes to a larger degree for classifying one's experience. Given that the IFC is associated with perceptual classification, the IFC involvement in perceptual organization should be larger when the classification part of the task becomes more complicated (i.e. when neither of the common categories fit one's perception).

We found different contributions of the AC and IFC to verbal transformations, as well as to auditory steaming. Glx concentrations in the AC were correlated with the durations of banana and nappa percepts, whereas GABA concentrations in the IFC were correlated with the proportion of the other percept. A simple interpretation is that the IFC involvement in verbal transformations depends on speech-specific mechanisms [37,59]. However, several researchers have argued that the IFC is associated with the generation of perceptual objects even in vision. For the apparent motion quartet, IFC activity occurs earlier during spontaneous perceptual switches but not during stimulus-driven changes [60]. Thus, the temporal precedence of the activation indicates that the IFC participates in initiating the formation of perceptual objects.

We did not find any significant correlation between auditory multistability and personality scales. By contrast, a recent study demonstrated that ego-resiliency is linked to switching patterns of auditory streaming [38]. In this study, a post hoc power analysis showed that more than 70 participants were needed to achieve a statistical power of 80% for significant correlations between ego-resiliency scores and switching patterns of auditory streaming (at the α-level of 0.05). This suggests that the lack of correlation in the current study was possibly due to low statistical power. Also we did not find any correlation between auditory multistability and response inhibition. Some theoretical models have postulated that perceptual switching is determined by the dynamics of mutual inhibition between neural populations representing each percept [21,22]. Our results suggest that neurochemical inhibition is not directly related to inhibition of a prepotent response at the cognitive level.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the dopamine tone of individuals is related to idiosyncratic switching patterns of auditory streaming and verbal transformations [16,17]. However, it is unclear what brain areas are influenced by the different neurotransmitter systems. This study suggests that AC Glx and IFC GABA concentrations are associated with auditory multistability. This is consistent with findings in the literature of auditory scene analysis, which has shown that perceptual organization involves an interaction between distributed neural circuits below, in and beyond AC [56,61,62]. Furthermore, our findings have clinical implications in that dysfunctions of the GABAergic and glutamatergic systems impact auditory perceptual organization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Keith Heberlein, Mark A. Brown and Heiko Meyer for providing a GABA spectral editing sequence (a work-in-progress version), and Yasuhiro Shimada and Takanori Kochiyama for helping with imaging data collection.

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics and Safety Committees of NTT Communication Science Laboratories and ATR-Promotions.

Data accessibility

Supplementary material includes a supplementary text, three figures and nine tables. The datasets supporting this article are available at https://figshare.com/s/0531ebc55884a85dd38d.

Authors' contributions

H.M.K., D.F., S.L.D. and I.W. designed the study and wrote the manuscript; H.M.K. and T.A. collected data; H.M.K., D.F., S.L.D. and T.A. analysed data; H.M.K., D.F. and I.W. interpreted data. All authors helped draft the manuscript and approved the final version of the article.

Competing interests

H.M.K. is the guest editor of the special issue.

Funding

This research was supported by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Lendület Project LP-36/2012 to D.F. and I.W.).

References

- 1.Bregman AS. 1990. Auditory scene analysis: the perceptual organization of sound. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz JL, Grimault N, Hupé JM, Moore BCJ, Pressnitzer D. 2012. Multistability in perception: binding sensory modalities, an overview. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367, 896–905. ( 10.1098/rstb.2011.0254) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kondo HM, van Loon AM, Kawahara J-I, Moore BCJ. 2017. Auditory and visual scene analysis: an overview. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160099 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0099) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelofi C, de Gardelle V, Egré P, Pressnitzer D. 2017. Interindividual variability in auditory scene analysis revealed by confidence judgements. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160107 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta AH, Jacoby N, Yasin I, Oxenham AJ, Shamma SA. 2017. An auditory illusion reveals the role of streaming in the temporal misallocation of perceptual objects. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160114 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Noorden LPAS. 1975. Temporal coherence in the perception of tone sequences, PhD thesis. Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands.

- 7.Pressnitzer D, Hupé JM. 2006. Temporal dynamics of auditory and visual bistability reveal common principles of perceptual organization. Curr. Biol. 16, 1351–1357. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.054) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bendixen A, Denham SL, Gyimesi K, Winkler I. 2010. Regular patterns stabilize auditory streams. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 128, 3658–3666. ( 10.1121/1.3500695) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denham S, Bõhm TM, Bendixen A, Szalárdy O, Kocsis Z, Mill R, Winkler I. 2014. Stable individual characteristics in the perception of multiple embedded patterns in multistable auditory stimuli. Front. Neurosci. 8, 25 ( 10.3389/fnins.2014.00025) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denham S, Bendixen A, Mill R, Tóth D, Wennekers T, Coath M, Bőhm T, Szalardy O, Winkler I. 2012. Characterising switching behaviour in perceptual multi-stability. J. Neurosci. Methods 210, 79–92. ( 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.04.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren RM. 1961. Illusory changes of distinct speech upon repetition—the verbal transformation effect. Br. J. Psychol. 52, 249–258. ( 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1961.tb00787.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warren RM, Gregory RL. 1958. An auditory analogue of the visual reversible figure. Am. J. Psychol. 71, 612–613. ( 10.2307/1420267) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warren RM. 1968. Verbal transformation effect and auditory perceptual mechanisms. Psychol. Bull. 70, 261–270. ( 10.1037/h0026275) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leopold DA, Logothetis NK. 1999. Multistable phenomena: changing views in perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 3, 254–264. ( 10.1016/S1364-6613(99)01332-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller SM, Hansell NK, Ngo TT, Liu GB, Pettigrew JD, Martin NG, Wright MJ. 2010. Genetic contribution to individual variation in binocular rivalry rate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 2664–2668. ( 10.1073/pnas.0912149107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kondo HM, Kitagawa N, Kitamura MS, Koizumi A, Nomura M, Kashino M. 2012. Separability and commonality of auditory and visual bistable perception. Cereb. Cortex 22, 1915–1922. ( 10.1093/cercor/bhr266) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashino M, Kondo HM. 2012. Functional brain networks underlying perceptual switching: auditory streaming and verbal transformations. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367, 977–987. ( 10.1098/rstb.2011.0370) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanai R, Bahrami B, Rees G. 2010. Human parietal cortex structure predicts individual differences in perceptual rivalry. Curr. Biol. 20, 1626–1630. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.027) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Genç E, Bergmann J, Singer W, Kohler A. 2011. Interhemispheric connections shape subjective experience of bistable motion. Curr. Biol. 21, 1494–1499. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson HR. 2003. Computational evidence for a rivalry hierarchy in vision. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14 499–14 503. ( 10.1073/pnas.2333622100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno-Bote R, Rinzel J, Rubin N. 2007. Noise-induced alternations in an attractor network model of perceptual bistability. J. Neurophysiol. 98, 1125–1139. ( 10.1152/jn.00116.2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noest AJ, van Ee R, Nijs MM, van Wezel RJA. 2007. Percept-choice sequences driven by interrupted ambiguous stimuli: a low-level neural model. J. Vis. 7, 1–14. ( 10.1167/7.8.10) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klink PC, van Ee R, van Wezel RJA. 2008. General validity of Levelt's propositions reveals common computational mechanisms for visual rivalry. PLoS ONE 3, e3473 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0003473) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huguet G, Rinzel J, Hupé JM. 2014. Noise and adaptation in multistable perception: noise drives when to switch, adaptation determines percept choice. J. Vis. 14, 19 ( 10.1167/14.3.19) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hohwy J, Roepstorff A, Friston K. 2008. Predictive coding explains binocular rivalry: an epistemological review. Cognition 108, 687–701. ( 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.05.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Logothetis NK. 2008. What we can do and what we cannot do with fMRI. Nature 453, 869–878. ( 10.1038/nature06976) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubenstein JLR, Merzenich MM. 2003. Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav. 2, 255–267. ( 10.1046/j.1601-183X.2003.00037.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Loon AM, Knapen T, Scholte HS, St. John-Saaltink E, Donner TH, Lamme VAF. 2013. GABA shapes the dynamics of bistable perception. Curr. Biol. 23, 823–827. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2013.03.067) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kihara K, Kondo HM, Kawahara JI. 2016. Differential contributions of GABA concentration in frontal and parietal regions to individual differences in attentional blink. J. Neurosci. 36, 8895–8901. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0764-16.2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeuchi T, Yoshimoto S, Shimada Y, Kochiyama T, Kondo HM. 2017. Individual differences in visual motion perception and neurotransmitter concentrations in the human brain. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160111 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edden RAE, Muthukumaraswamy SD, Freeman TCA, Singh KD. 2009. Orientation discrimination performance is predicted by GABA concentration and gamma oscillation frequency in human primary visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 29, 15 721–15 726. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4426-09.2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snyder JS, Gregg MK, Weintraub DM, Alain C. 2012. Attention, awareness, and the perception of auditory scenes. Front. Psychol. 3, 15 ( 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore BCJ, Gockel HE. 2012. Properties of auditory stream formation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367, 919–931. ( 10.1098/rstb.2011.0355) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bendixen A. 2014. Predictability effects in auditory scene analysis: a review. Front. Neurosci. 8, 60 ( 10.3389/fnins.2014.00060) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Windmann S, Wehrmann M, Calabrese P, Güntürkün O. 2006. Role of the prefrontal cortex in attentional control over bistable vision. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 18, 456–471. ( 10.1162/089892906775990570) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knapen T, Brascamp J, Pearson J, van Ee R, Blake R. 2011. The role of frontal and parietal brain areas in bistable perception. J. Neurosci. 31, 10 293–10 301. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1727-11.2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kondo HM, Kashino M. 2007. Neural mechanisms of auditory awareness underlying verbal transformations. Neuroimage 36, 123–130. ( 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farkas D, Denham SL, Bendixen A, Tóth D, Kondo HM, Winkler I. 2016. Auditory multi-stability: idiosyncratic perceptual switching patterns, executive functions and personality traits. PLoS ONE 11, e0154810 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0154810) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.John OP, Srivastava S. 2001. The big-five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In Handbook of personality: theory and research, 2nd edn (eds Pervin LA, John OP), pp. 102–138. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. 2001. The five factor model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers. Individ. Dif. 30, 669–689. ( 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Block JH, Kremen AM. 1996. IQ and ego-resiliency: conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 349–361. ( 10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.349) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farkas D, Orosz G. 2015. Ego-resiliency reloaded: a three-component model of general resiliency. PLoS ONE 10, e0120883 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0120883) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. 2000. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex ‘frontal lobe’ tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn. Psychol. 41, 49–100. ( 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oldfield RC. 1971. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9, 97–113. ( 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edden RAE, Puts NAJ, Harris AD, Barker PB, Evans CJ. 2014. Gannet: a batch-processing tool for the quantitative analysis of gamma-aminobutyric acid-edited MR spectroscopy spectra. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 40, 1445–1452. ( 10.1002/jmri.24478) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mullins PG, McGonigle DJ, O'Gorman RL, Puts NAJ, Vidyasagar R, Evans CJ, Edden RAE. 2014. Current practice in the use of MEGA-PRESS spectroscopy for the detection of GABA. Neuroimage 86, 43–52. ( 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.12.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farkas D, Denham SL, Bendixen A, Winkler I. 2016. Assessing the validity of subjective reports in the auditory streaming paradigm. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 139, 1762–1772. ( 10.1121/1.4945720) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moreno-Bote R, Shpiro A, Rinzel J, Rubin N. 2010. Alternation rate in perceptual bistability is maximal at and symmetric around equi-dominance. J. Vis. 10, 1–18. ( 10.1167/10.11.1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Denham SL, Winkler I. 2006. The role of predictive models in the formation of auditory streams. J. Physiol. Paris 100, 154–170. ( 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2006.09.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kruskal JB. 1964. Multidimensional scaling by optimizing goodness of fit to a nonmetric hypothesis. Psychometrika 29, 1–27. ( 10.1007/BF02289565) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Micheyl C, Tian B, Carlyon RP, Rauschecker JP. 2005. Perceptual organization of tone sequences in the auditory cortex of awake macaques. Neuron 48, 139–148. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.039) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gutschalk A, Micheyl C, Melcher JR, Rupp A, Scherg M, Oxenham AJ. 2005. Neuromagnetic correlates of streaming in human auditory cortex. J. Neurosci. 25, 5382–5388. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0347-05.2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Micheyl C, Carlyon RP, Gutschalk A, Melcher JR, Oxenham AJ, Rauschecker JP, Tian B, Wilson EC. 2007. The role of auditory cortex in the formation of auditory streams. Hear. Res. 229, 116–131. ( 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson EC, Melcher JR, Micheyl C, Gutschalk A, Oxenham AJ. 2007. Cortical fMRI activation to sequences of tones alternating in frequency: relationship to perceived rate and streaming. J. Neurophysiol. 97, 2230–2238. ( 10.1152/jn.00788.2006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brascamp J, Blake R, Knapen T. 2015. Negligible fronto-parietal BOLD activity accompanying unreportable switches in bistable perception. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1672–1678. ( 10.1038/nn.4130) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kondo HM, Kashino M. 2009. Involvement of the thalamocortical loop in the spontaneous switching of percepts in auditory streaming. J. Neurosci. 29, 12 695–12 701. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1549-09.2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cusack R. 2005. The intraparietal sulcus and perceptual organization. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 17, 641–651. ( 10.1162/0898929053467541) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Teki S, Chait M, Kumar S, von Kriegstein K, Griffiths TD. 2011. Brain bases for auditory stimulus-driven figure-ground segregation. J. Neurosci. 31, 164–171. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3788-10.2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sato M, Beciu M, Lœvenbruck H, Schwartz JL, Cathiard MA, Segebarth C, Abry C. 2004. Multistable representation of speech forms: a functional MRI study of verbal transformations. Neuroimage 23, 1143–1151. ( 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.055) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sterzer P, Kleinschmidt A. 2007. A neural basis for inference in perceptual ambiguity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 323–328. ( 10.1073/pnas.0609006104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kondo HM, Pressnitzer D, Toshima I, Kashino M. 2012. Effects of self-motion on auditory scene analysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6775–6780. ( 10.1073/pnas.1112852109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schadwinkel S, Gutschalk A. 2011. Transient bold activity locked to perceptual reversals of auditory streaming in human auditory cortex and inferior colliculus. J. Neurophysiol. 105, 1977–1983. ( 10.1152/jn.00461.2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary material includes a supplementary text, three figures and nine tables. The datasets supporting this article are available at https://figshare.com/s/0531ebc55884a85dd38d.